In light of the $5 billion EU antitrust ruling against Google this week, we started noticing a certain classic Ars story circulating around social media. Google's methods of controlling the open source Android code and discouraging Android forks is exactly the kind of behavior the EU has a problem with, and many of the techniques outlined in this 2013 article are still in use today.

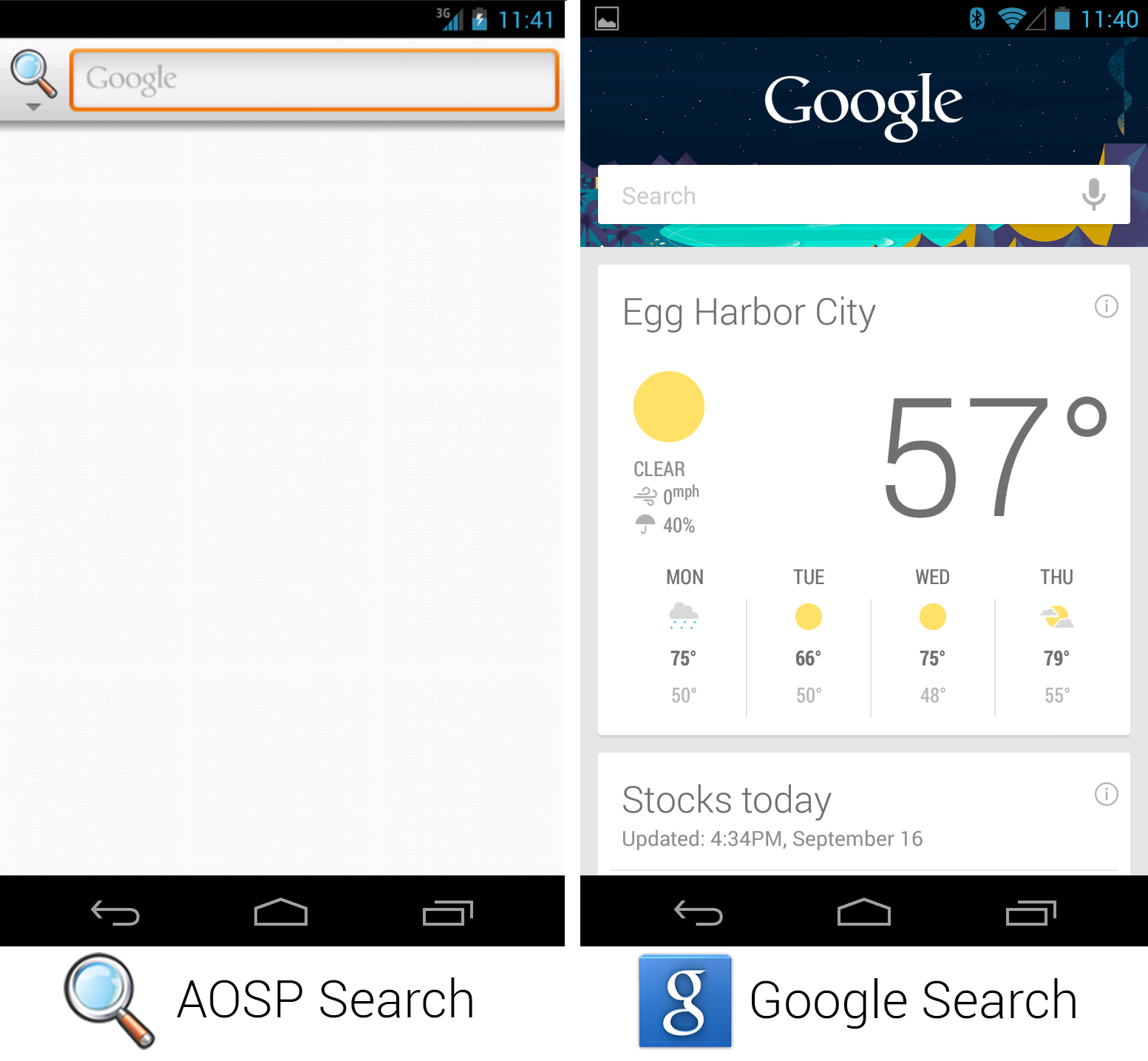

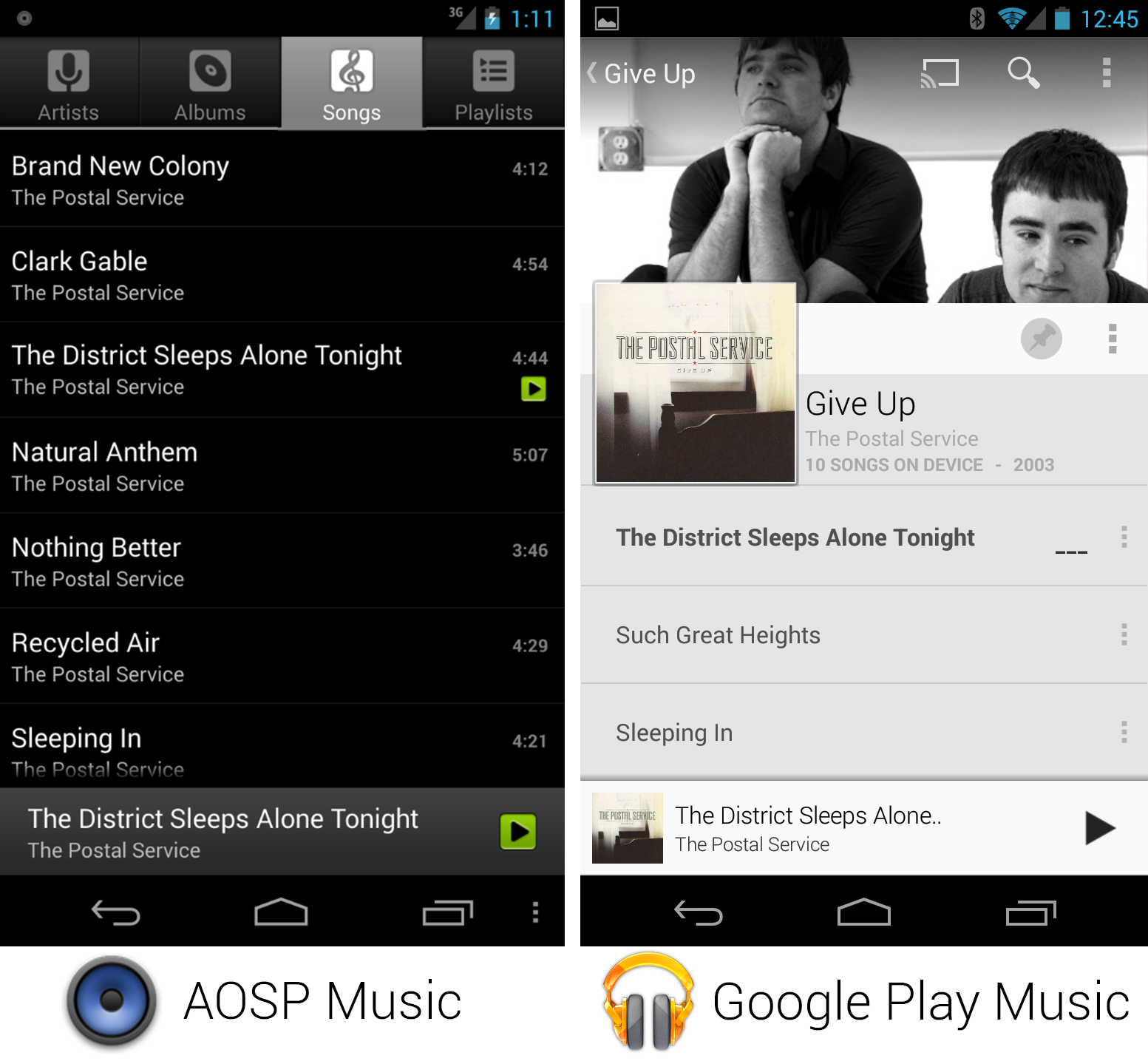

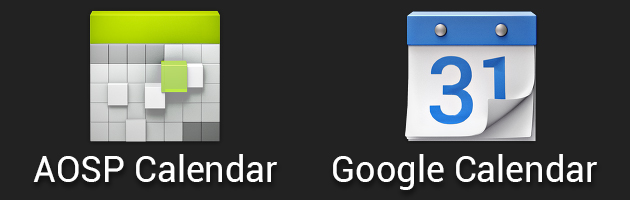

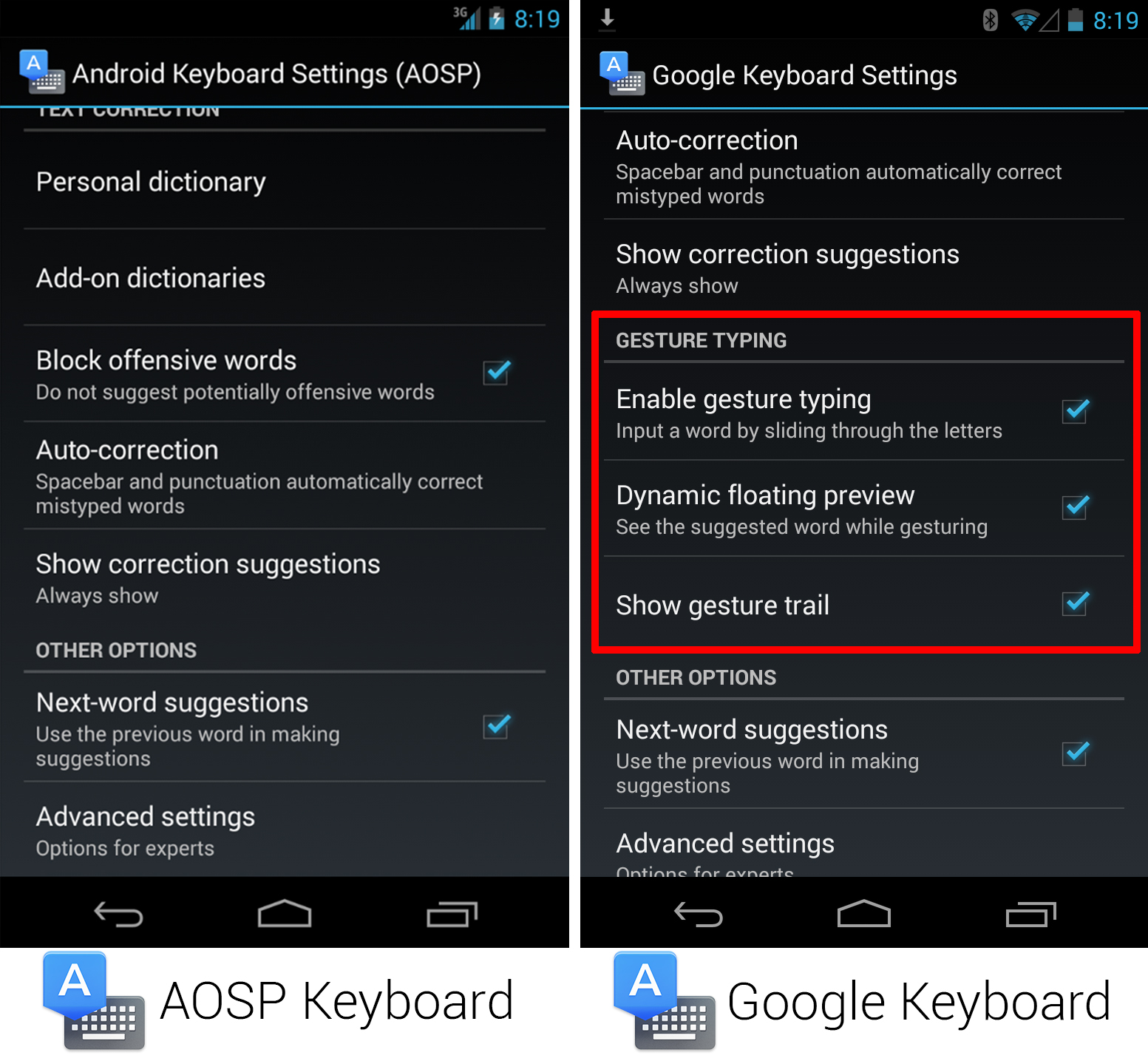

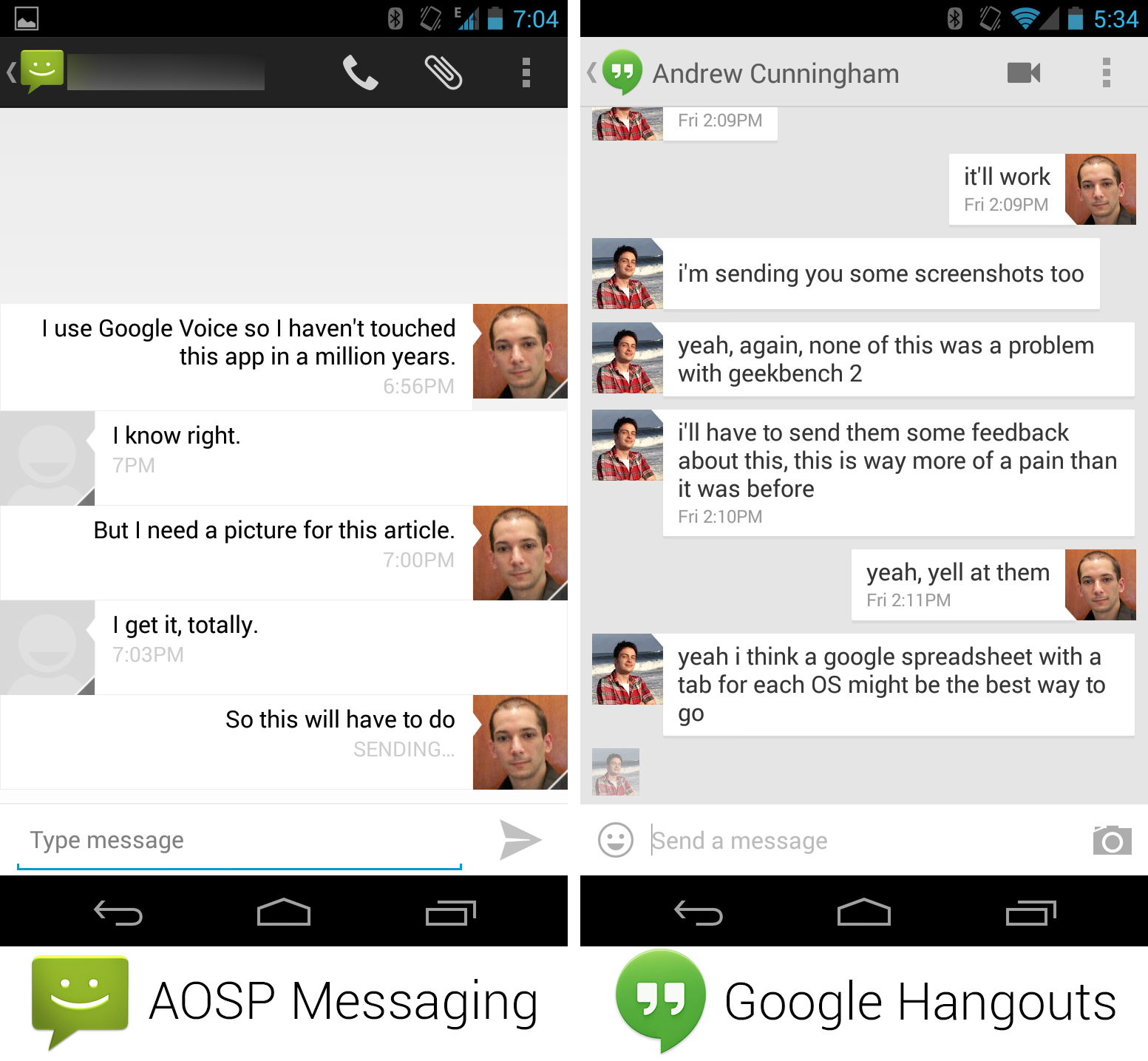

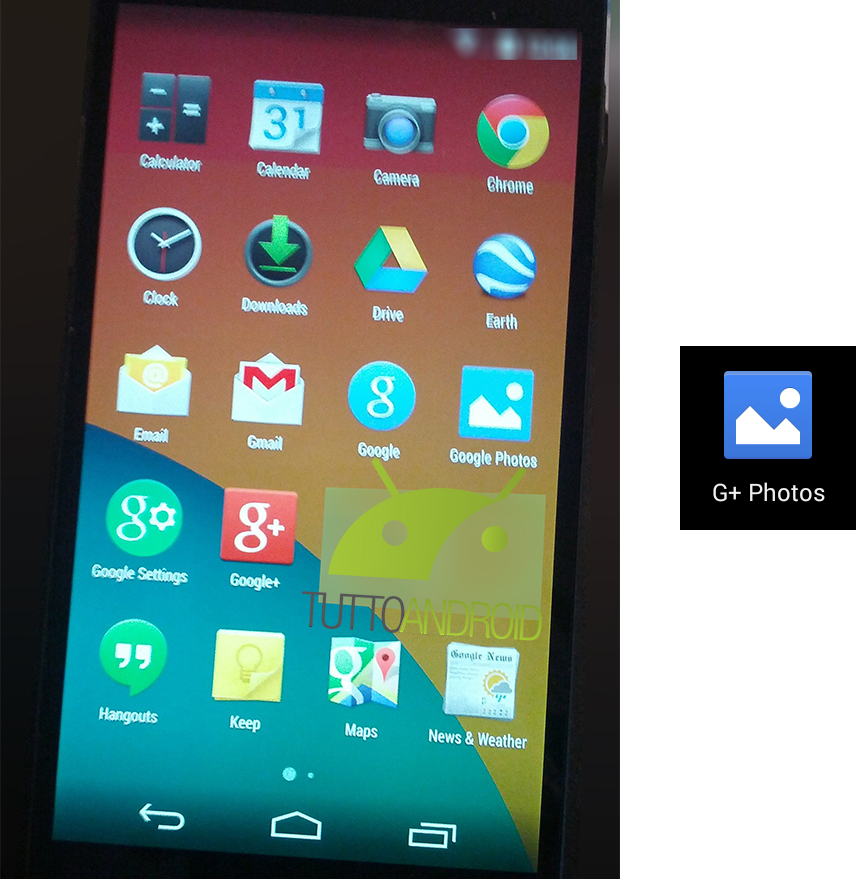

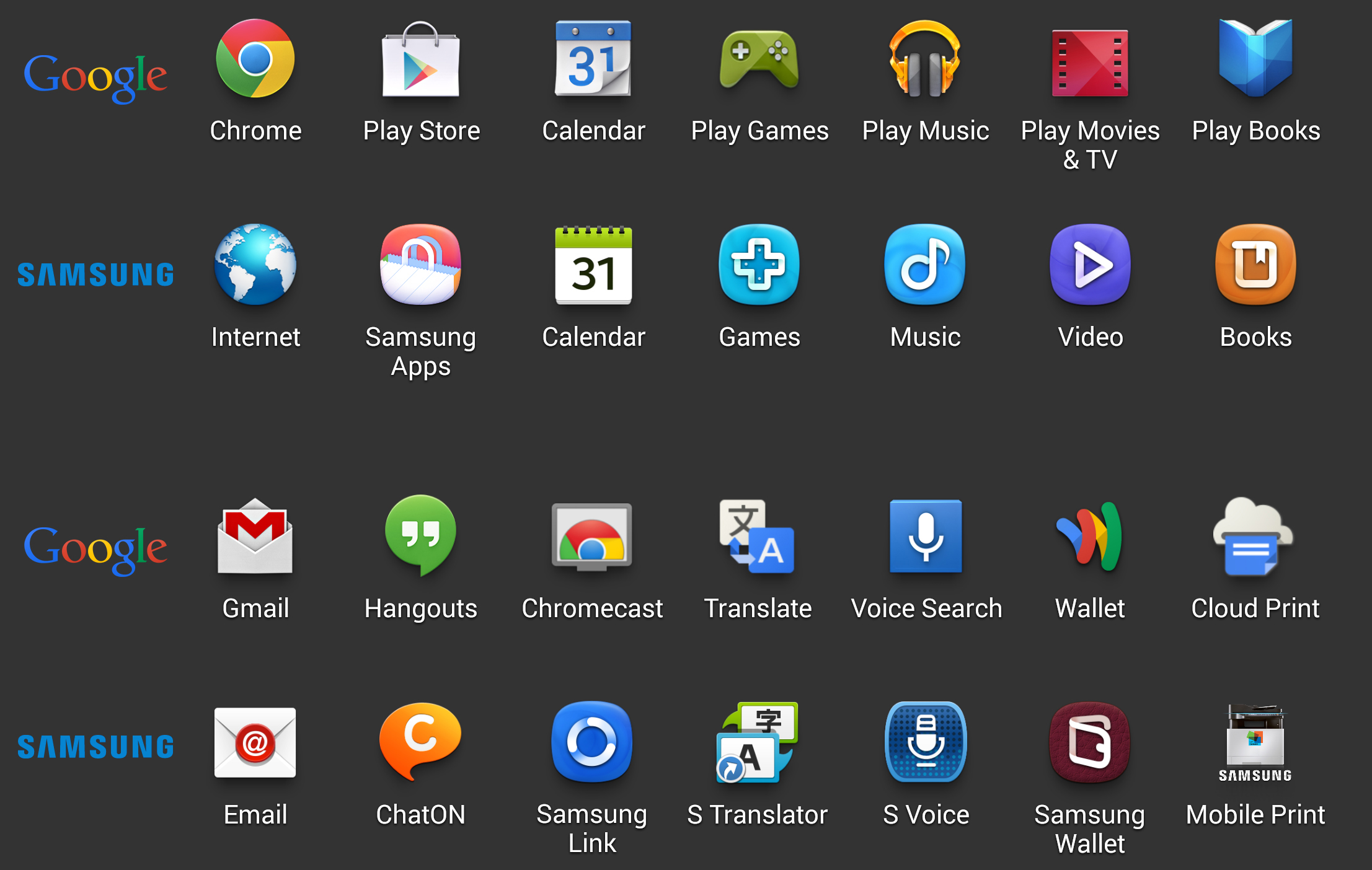

The idea of a sequel to this piece has come up a few times, but Google's Android strategy of an open source base paired with key proprietary apps and services hasn't really changed in the last five or so years. There have been updates to Google's proprietary apps so that they look different from the screenshots in this article, but the base strategy outlined here is still very relevant. So in light of the latest EU development, we're resurfacing this story for the weekend. It first ran on October 20, 2013 and appears largely unchanged—but we did toss in a few "In 2018" updates anywhere they felt particularly relevant.Six years ago, in November 2007, the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) was announced. The original iPhone came out just a few months earlier, capturing people's imaginations and ushering in the modern smartphone era. While Google was an app partner for the original iPhone, it could see what a future of unchecked iPhone competition would be like. Vic Gundotra, recalling Andy Rubin's initial pitch for Android, stated:

He argued that if Google did not act, we faced a Draconian future, a future where one man, one company, one device, one carrier would be our only choice.

Google was terrified that Apple would end up ruling the mobile space. So, to help in the fight against the iPhone at a time when Google had no mobile foothold whatsoever, Android was launched as an open source project.

In that era, Google had nothing, so any adoption—any shred of market share—was welcome. Google decided to give Android away for free and use it as a trojan horse for Google services. The thinking went that if Google Search was one day locked out of the iPhone, people would stop using Google Search on the desktop. Android was the "moat" around the Google Search "castle"—it would exist to protect Google's online properties in the mobile world.

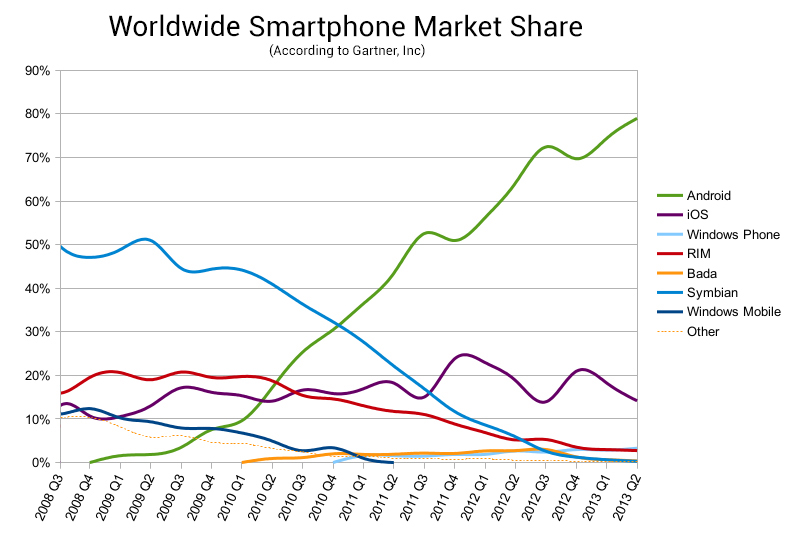

Today, things are a little different. Android went from zero percent of the smartphone market to owning nearly 80 percent of it. Android has arguably won the smartphone wars, but "Android winning" and "Google winning" are not necessarily the same thing. Since Android is open source, it doesn't really "belong" to Google. Anyone is free to take it, clone the source, and create their own fork or alternate version.

As we've seen with the struggles of Windows Phone and Blackberry 10, app selection is everything in the mobile market, and Android's massive install base means it has a ton of apps. If a company forks Android, the OS will already be compatible with millions of apps; a company just needs to build its own app store and get everything uploaded. In theory, you'd have a non-Google OS with a ton of apps, virtually overnight. If a company other than Google can come up with a way to make Android better than it is now, it would be able to build a serious competitor and possibly threaten Google's smartphone dominance. This is the biggest danger to Google's current position: a successful, alternative Android distribution.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...