"The very nature of digital [history] is that it's both inherently easy to save and inherently easy to utterly destroy forever."

Jason Scott knows what he's talking about when it comes to the preservation of digital software. At the Internet Archive, he's collected thousands of classic games, pieces of software, and bits of digital ephemera. His sole goal is making those things widely available through the magic of browser-based emulation.

Compared to other types of archaeology, this kind of preservation is still relatively easy for now. While the magnetic and optical disks and ROM cartridges that hold classic games and software will eventually be rendered unusable by time, it’s currently pretty simple to copy their digital bits to a form that can be preserved and emulated well into the future.

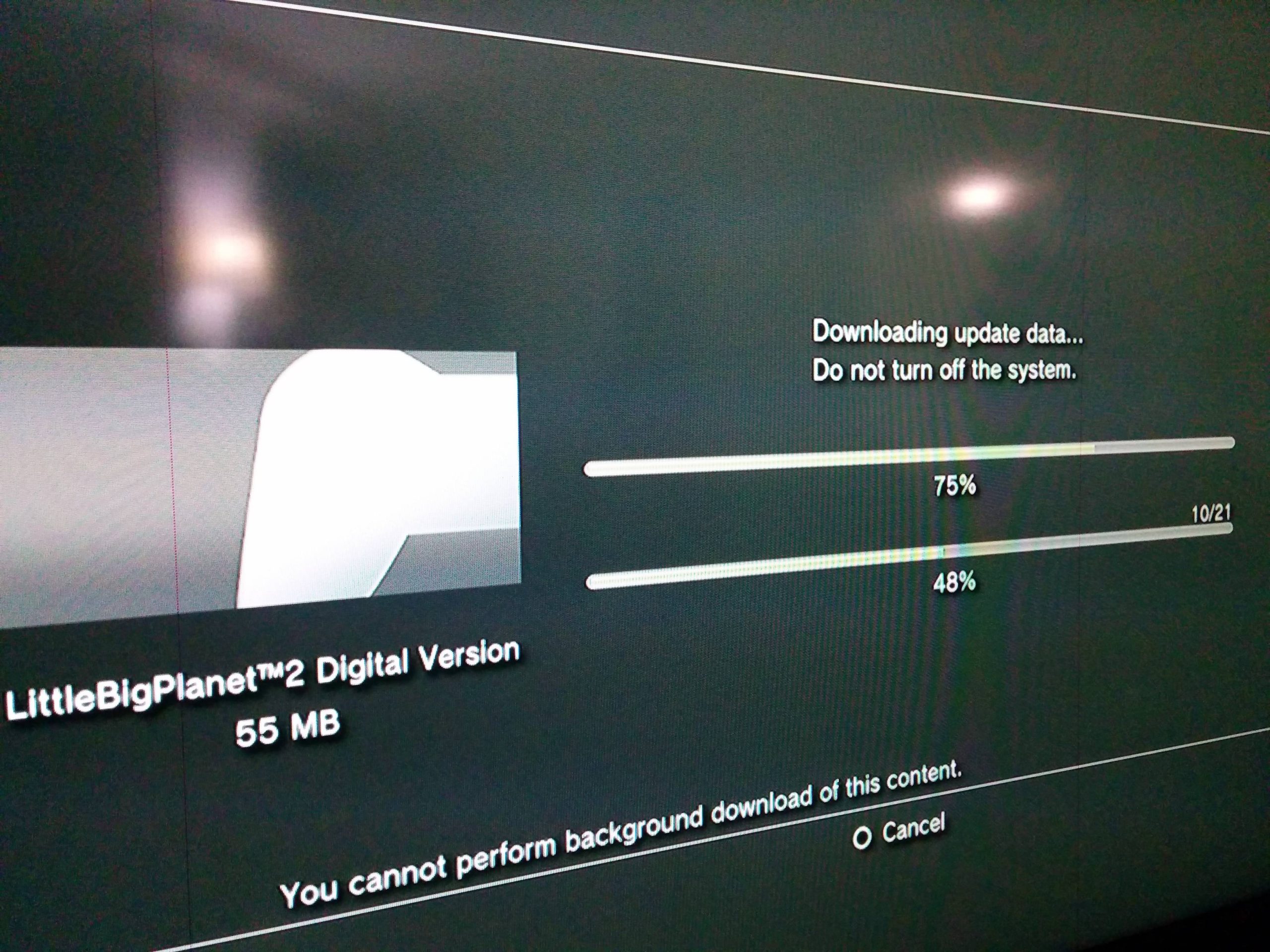

But paradoxically, an Atari 2600 cartridge that’s nearly 40 years old is much easier to preserve at this point than many games released in the last decade. Thanks to changes in the way games are being distributed, protected, and played in the Internet era, large parts of what will become tomorrow's video game history could be lost forever. If we're not careful, that is.

Throwing away the layers

In an industry with a nearly constant focus on the latest and greatest, it may seem silly to want to preserve old, outdated versions of today's games for posterity. But the current nostalgic and research interest in games from the ’70s and ’80s shows just how important it is to try to save a complete record of today’s titles, as ephemeral as they sometimes are.

"I totally get that people look at this and say all of this game history stuff is navel-gazing bullshit... an irrelevant, wasteful, trivial topic,” Scott told Ars. “[But] mankind is poorer when you don't know your history, all of your history, and the culture is poorer for it. It doesn't matter if it's games or civil wars or highways or government machinations. If you don't have that historical context, you make poorer decisions, you make the same mistakes again and again, and you end up with an eternal present. You don't understand where things are and where they're going, because you're constantly in the now."

Loading comments...

Loading comments...