| Austerlitz:

Battle of Three Emperors

By Bill Bodden

January 2016

In the two years prior to 1805, France had a substantial

portion of its armed forces camped on the Normandy coast preparing

for an invasion of England. In August 1805 the Emperor Napoleon,

having decided an invasion was impractical as long at British

seapower remained dominant, turned his back on England for

the time and marched instead toward continental Europe and

the threat posed by the Third Coalition.

Flush with cash from reparations owed France from the campaigns

of 1800, concluded by the Treaty of Amiens in late March 1802,

and also from the sale of the Louisiana Territory to the fledgling

United States, Napoleon gathered his forces and trained them

well. By 1805 Le Grand Armee was the best-trained army in

the world.

A series of diplomatic moves between France and England, namely

French embargoes placed on British shipping, led to a declaration

of war. Britain’s navy now blockaded French ports and

began to agitate against the French in Europe, forming an

alliance to oppose the armed might of the Emperor, still camped

inconveniently close just across the English Channel.

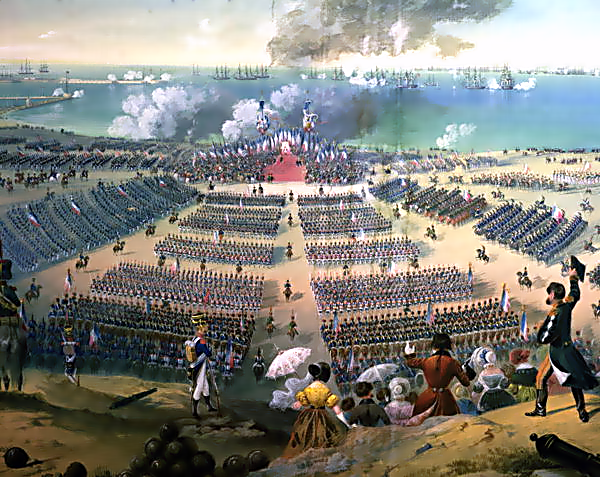

Le Grande Armee at Boulogne, August 1804

At the same time, rumors reached Napoleon’s ear of a

plot to restore the Bourbon family to the French throne. The

main subject of these rumors was the duke of Enghien, living

in exile in the neutral German state of Baden. Tired of years

of plotting against himself and his family, Napoleon ordered

the duke arrested, no matter that he was in another country

altogether. The duke was arrested and repatriated to France,

where he was tried, sentenced and executed. This was the final

straw as far as the other monarchs of Europe were concerned.

Seeing their own potential fate at the hands of Napoleon,

they all too eagerly agreed to Britain’s plan.

This Alliance, the Third Coalition, was struck between Austria,

Britain and Russia. Britain agreed to provide much of the

cash up front to finance the war, as long as Russia and Austria

came through with the manpower. The Third Coalition was an

uneasy alliance at best; neither the Russians nor the Austrians

completely trusted each other, being rivals in the Balkans

and Eastern Europe, and this suspicion led to a lack of co-operation

between the two empires at critical times.

Austria, still stinging from the loss of much of its Italian

territory to the French after the Treaty of Amiens, had been

reorganizing its armed forces. The Austrian Imperial Court

was constantly embroiled in scheming and shifting allegiances;

General Karl Mack was the darling of the faction that favored

war, and managed to convince the Austrian Emperor Franz that,

despite a military career where he was better known for being

a solid staff officer and administrator rather than field

commander, and his command of a disastrous campaign against

the French in Italy only five years previously where his own

troops turned on him, he was the one who could speed up military

reforms and have the army ready to meet Napoleon in only a

matter of months. Austria was also counting on support from

neighboring countries, including Bavaria, despite the latter’s

strong ties to France. These blindly optimistic ideas would

cost Austria dearly before the year was over.

General Mack's Army

General Mack set to work organizing the Austrian Army for

the coming campaign. In September 1805 he marched his army

north into Bavaria expecting the Bavarians to join him; instead,

having concluded a secret treaty with the French, the Bavarians

withdrew north and west to buy time for the French army to

arrive. Mack and the Austrians were dismayed, yet stayed in

a relatively forward position in Bavaria in the fortress-city

of Ulm, thinking themselves safe with a river between them

and Napoleon.

It is argued that one of Napoleon’s great strengths

as a military leader was his ability to move large masses

of troops much more quickly than expected. In this advance

he overran a number of smaller garrisons, meeting little resistance

from an Austrian army demoralized by Mack’s poor planning

and by their lack of adequate supplies, especially food. Bonaparte

drove his men hard, and their sweat and toil paid off when

they encircled Ulm and trapped roughly half of the entire

Austrian northern army inside the city.

Except for a few early skirmishes with the vanguard of the

French army, Mack had done little to keep himself informed

as to what was transpiring in the world outside Ulm, and the

French to caught him napping. Within Ulm the story was even

worse than it appeared. Surrounded and with little food and

less ammunition, the Austrians were in a very bad position

indeed. Their only hope lay in the speedy arrival of the Russian

army to break the siege and relieve them.

For their part, the Russians were doing the best they possibly

could. Three Russian armies were on the march; General Benningson’s

northern army marched across Prussia and into Austria near

present-day Prague; General Kutusov, the overall commander

of the Russian forces, marched straight through Austria; General

Buxhowden’s army brought up the rear, positioned partway

between the line of march of the other two forces so he could

come to the aid of either Benningson or Kutusov if needed.

Having been on the move since August — setting off barely

two weeks after Austria officially joined the Third Coalition

— the Russians had covered hundreds of miles but were

still many miles away. Winter was approaching, and the autumn

rains were turning every road into a river of thick mud. Despite

the army being largely on foot, progress was good, but the

clock was ticking away on the Austrians trapped inside the

walls of Ulm. By October 16 the Russians had covered over

600 miles but were still 160 miles away from Ulm —

at least ten days’ march if the weather was good, and

they would need a few days after arriving to regroup and organize

themselves once they arrived. In the end, it was two weeks

before they would reach the vicinity of Ulm; by then it was

too late.

General Mack, despairing of Russian salvation from the French,

surrendered the entire army bottled up in Ulm, more than 25,000

men, as prisoners of war. General Jellacic’s column,

another 8,000 Austrian troops, surrendered in the Tyrol valley

in Austria, to the south of Mack’s position. General

Werneck’s column to the north also surrendered. More

than three-quarters of the northern Austrian army was already

out of the way; those that were left (some cavalry had escaped

capture at Ulm, and General Kienmayer’s eastern column

was largely untouched) retreated east to join up with the

advancing Russians. On October 25, 1805, only two weeks after

initial contact with the French, the grand battle plan of

the Third Coalition was in tatters.

Now Napoleon turned his attention to the approaching Russians.

Archduke Charles, sent to keep a large part of Napoleon’s

army busy in northern Italy at the outset of hostilities (and

to keep him out of the way of General Mack, whom Charles considered

unfit for command), marched north after a modest victory against

the French at Caldiero in Italy with some 30,000 men, hoping

to link up with the remnants of the northern army and the

Russians. The going was slow, and his troops were in poor

shape. Still, Charles did himself and Austria no favors by

resting his troops for two whole days while the French closed

in on the Austrian capital of Vienna.

On his way to Vienna after being released on parole by the

French, the unfortunate General Mack informed the Russians

of what had happened, then proceeded to the Austrian capital

and his eventual court-martial. After receiving the news of

the disaster at Ulm, Kutusov began to retreat from Napoleon,

buying time for the rest of Russia’s armies to unite,

and looking for good ground on which to challenge the French

emperor.

Napoleon had his army swing north, sweeping through Vienna

in an effort to have his easternmost divisions swing around

behind the Russians, virtually encircling them. The French

were aided in this pursuit by the Austrians themselves, who

treated Napoleon more like a conquering hero than a hated

enemy, even allowing French troops free and unimpeded access

to bridges that could have been destroyed to slow his progress.

The Austrians, it seems, were more afraid of their plundering

allies than of the French. The Russians were behaving as if

in enemy territory, looting as they passed.

The Russians continued to fall back, spending all of November

skirmishing with the French and looking for a good position

while waiting for the full strength of all three armies to

converge. The remnants of the northern Austrian Army had linked

up, and soon it began to turn for the showdown to come. On

December 2, 1805, more than 140,000 men would contest the

Moravian ground near the town of Austerlitz while the whole

of Europe held its collective breath.

General Mack surrenders at Ulm. By Charles Thevenin.

Posturing and Negotiations

Napoleon had secretly scouted the area around Austerlitz some

weeks earlier, and had chosen the area as the perfect place

to spring his trap on the unsuspecting Allies. The Allies

thought themselves in a quite good position as well, and had

things gone as planned they may have been correct.

To the north, the Prussian government was watching developments

with interest. Napoleon had offered Prussia the city-state

of Hanover in exchange for Prussia’s neutrality in the

conflict. Prussia had not officially accepted yet, and had

secretly decided to join the Allies against the French after

the end of 1805. Meanwhile, the Prussians watched and waited.

The Russian army was nominally under the overall command

of Mikhail Kutusov, an able but cautious commander with over

40 years’ military experience leading troops into

battle. In reality, Tsar Alexander, who had joined the army

once it had reached close proximity with the enemy, was truly

in charge. The Tsar, perfectly capable of drilling troops

expertly but with no real combat command experience, was heavily

influenced by a faction in the Russian Imperial Court who

favored aggressive action. These fire-eaters, convinced that

glory was a superior consideration to any other, convinced

the Tsar to ignore Kutusov’s sound but drab battle plan,

much to the detriment of the Allies’ chances for victory.

On November 29, French cavalry evacuated a small plateau,

called the Pratzeberg Heights, which they had been holding

east of the village of Austerlitz. It was a calculated move

on Napoleon’s part, and the Allies took the bait, occupying

those same heights in force only a few hours later. Napoleon

sent a trusted aide to the Allies encampment under a flag

of truce. He was to make opening overtures toward a cease-fire,

by his very presence suggesting that the French were not prepared

for battle. Secretly he was there to gather information.

It was painfully apparent that the Allied high command not

only lacked unity but was filled with outright dissent. Russian

Prince Dolgoruky returned with the aide to the French field

headquarters and began to make demands of Napoleon himself

as conditions for peace. Napoleon, meanwhile, made sure that

the prince would see only what the French emperor had wanted

him to see. When the meeting concluded he was even more confident

that his plan was working perfectly. After seeing only cavalry

around Napoleon’s camp, Prince Dolgoruky returned with

news that the French were not only unprepared for battle,

they were withdrawing.

Having tricked the Allies into consuming an entire day with

fruitless negotiations, Napoleon had purchased sufficient

time for his army to form up where he needed them, and for

his outlying divisions to make their way to the battle site.

On the morning of December 2, the Allies started forward,

convinced they would be pursuing the French army as it retreated.

Having spent the night in freezing cold, they were ready for

a fight. They immediately discovered their error as several

French infantry divisions met them and held firm.

As the battle of Austerlitz began in earnest, the majority

of the battlefield was shrouded with a thick fog. In the center

of the French line stood Marshal Soult’s IV Corps, some

22,000 men in total. His Corps hidden in a deep depression

by the fog, Soult’s advance towards the Pratzeberg Heights

at 9 A.M. was a shock that nearly unnerved the Allies forces.

Bataille d'Austerlitz, by François Pascal

Simon Gérard.

Rout from the Heights

On the Allies’ extreme left, the Austrian infantry had

begun to advance, probing the French positions. After a brief

initial success they were thrown back by the timely arrival

of several battalions’ worth of French infantry, beginning

a see-saw struggle for tactically important structures at

the south end of the battlefield. Napoleon was presenting

his forces in strength on the Allies’ right, appearing

to leave his own right weak and vulnerable.

The Allies were convinced by this showing, and began to concentrate

a large portion of their troops from the center to the south,

hoping to break through the weak left and sweep these broken

forces north, encircling the entire French army. Unknown to

the Allies, Marshal Davout had come up from the southwest

with a fraction of the III Corps, some 4,000 infantry and

cavalry, as an advance force to bolster the supposedly weak

French left.

In the north, marshals Murat and Lannes were trusted with

keeping the Allied Fifth Column pinned down. With the exodus

of the troops from the center to assault the French right

to the south, General Bagration’s column was virtually

isolated. Lannes sent two regents forward to begin the encirclement,

but they ran into stubborn resistance from a small group of

Russian infantry. This resistance bought enough time for Bagration

to extricate himself, but not before a tremendous artillery

exchange, and a running duel between of the Russian Imperial

Guard cavalry and Murat’s cavalry reserve.

In the center, Soult’s massive Corps now began an advance

up the Pratzeburg Heights, filling the gap left by the Allies’

move against the French right. This advance by Soult was intended

to split the Allied forces in half, and would provide the

French the opportunity to overwhelm the Allies piece by piece,

starting with the northernmost wing and rolling south along

the plateau.

Marshal Bernadotte had arrived during the night with his

I Corps, and was held in reserve in the rear of the French

lines; his troops were hidden from the Allies’ view

behind a line of hills along with several battalions of French

grenadiers.

In panic the Allies sent forces to reinforce the Pratzeburg

Heights, but to little avail; Napoleon’s forces had

driven off most of the force left there held against the reinforcements

until Bernadotte’s corps and the grenadiers were sent

to help. The battle was turning into a rout. Emperors Francis

of Austria and Alexander of Russia both quit the field.

The French moved to the south of the heights, in a perfect

position to bombard those troops of the Allies that had so

recently enjoyed that same view. Attempting to escape the

encircling French army, the First and Second Columns of the

Allies found themselves in a tight spot; due to French pursuit,

they had a large portion of their retreat rout blocked by

a frozen lake. As the troops began to cross the ice, French

bombardment followed, further panicking the retreating troops

and driving them into the frozen lake in droves. The ice was

not thick enough to support the weight of all those men, horses

and artillery pieces. It gave way. A few hundred men sank

to a frigid, watery grave. Many others scrambled to shore,

but in their terror and confusion many wound up prisoners

of war, and very few artillery pieces crossed the ice unscathed.

Napoleon had achieved what is arguably his most brilliant

victory.

In the aftermath of Austerlitz, the Russians retreated back

across the frontier to their homeland, leaving the Austrians

and French to sort things out. Austrian Emperor Francis applied

to Napoleon for an armistice, and before the end of the month

had signed the Treaty of Pressburg, ceding significant portions

of the once-proud Holy Roman Empire to French control. These

lands would be used to form the Confederation of the Rhine,

a series of small, sovereign Germanic States loyal to Napoleon,

acting as a buffer zone to separate the French from Prussia

and Austria. These nations and city-states would contribute

significant forces to Napoleon’s future war efforts,

even fighting with the French during the Russian Campaign

of 1812.

The Austerlitz Campaign could not have gone better for the

French, while the Allies were left with the felling that they

couldn’t do anything right. A large indemnity would

hamper the Austrian economy for years to come and keep the

French coffers well-stocked.

With the struggle over so quickly, Prussia, which had planned

to enter the war on the Allies’ side after the first

of the year, decided instead to accept Napoleon’s offer

of the city of Hanover and related territories in exchange

for their neutrality. Now Britain was alone in opposing the

ambitious Bonaparte — although rumblings from Prussia

in 1806 would lead to another decisive campaign, and the humbling

of another great European power.

Don’t wait to put Soldier Emperor on your game table! Join the Gold Club and find out how to get it before anyone else!

|