Abstract

We have analyzed the NH2CHO, HNCO, H2CO, and CH3CN (13CH3CN) molecular lines at an angular resolution of ∼0 3 obtained by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array Band 6 toward 30 high-mass star-forming regions. The NH2CHO emission has been detected in 23 regions, while the other species have been detected toward 29 regions. A total of 44 hot molecular cores (HMCs) have been identified using the moment 0 maps of the CH3CN line. The fractional abundances of the four species have been derived at each HMC. In order to investigate pure chemical relationships, we have conducted a partial correlation test to exclude the effect of temperature. Strong positive correlations between NH2CHO and HNCO (

3 obtained by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array Band 6 toward 30 high-mass star-forming regions. The NH2CHO emission has been detected in 23 regions, while the other species have been detected toward 29 regions. A total of 44 hot molecular cores (HMCs) have been identified using the moment 0 maps of the CH3CN line. The fractional abundances of the four species have been derived at each HMC. In order to investigate pure chemical relationships, we have conducted a partial correlation test to exclude the effect of temperature. Strong positive correlations between NH2CHO and HNCO (

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

Prebiotic molecules or precursors of organic matter, which are important for life, have been fervently explored in the interstellar medium (ISM) in recent years. Observations toward the molecular cloud G0.693-0.027 near the Galactic Center have reported the detection of molecules that are related to life; e.g., ethanolamine (NH2CH2CH2OH; Rivilla et al. 2021a), cyanomidyl radical (HCNC; Rivilla et al. 2021b), and (Z)-1,2-ethenediol ((CHOH)2; Rivilla et al. 2022). The detection of these species implies that the building blocks of life on Earth may have formed at the early stages of star formation. However, our current knowledge about the evolution of molecules, from simple molecules through the complex ones to biomolecules, is still lacking.

Formamide (NH2CHO), the simplest possible amide, has been considered to be a potential prebiotic molecule (e.g., López-Sepulcre et al. 2019). This molecule contains a peptide bond that connects amino acids to form proteins. Its first detection in the ISM was achieved toward the Sagittarius B2 (Sgr B2) high-mass star-forming region (Rubin et al. 1971). More complex molecules including a peptide bond have been detected in the ISM; e.g., acetamide (CH3CONH2; Hollis et al. 2006) and N-methylformamide (CH3NHCHO; Belloche et al. 2017; Ligterink et al. 2020). Formamide could be related to these more complex molecules; thus it is important to reveal their chemistry in the ISM. Isocyanic acid (HNCO) has been considered as a precursor of NH2CHO. It was first discovered in the ISM from Sgr B2 (Snyder & Buhl 1972), soon after the detection of NH2CHO. Although their presence in the ISM has been known for 50 yr, their chemistry is still debated.

Tight correlations between NH2CHO and HNCO have been found in observational studies. López-Sepulcre et al. (2015) derived a power-law relationship of X(NH2CHO) = 0.04X(HNCO)0.93 from observational results toward young stellar objects (YSOs) with various stellar masses. Ligterink et al. (2020) investigated chemical links among several amide molecules toward the high-mass star-forming region NGC 6334I. They found that the HNCO/NH2CHO abundance ratios in this region are consistent with the average interstellar trend, and suggested that this result strengthens the probable link between HNCO and NH2CHO. Law et al. (2021) investigated the spatial distribution of several complex organic molecules (COMs) toward the OB cluster-forming region G10.6-0.4, and found a spatial correlation between HNCO and NH2CHO. Such a correlation supports that hydrogenation of HNCO on dust surfaces is a major formation route for NH2CHO (e.g., Mendoza et al. 2014; López-Sepulcre et al. 2015, 2019; Song & Kästner 2016).

A gas-phase reaction between NH2 and H2CO has been investigated by quantum calculations and proposed as another formation route of NH2CHO (Barone et al. 2015). This reaction has been found to be barrierless and can proceed even in low-temperature conditions. Skouteris et al. (2017) reanalyzed this reaction and proposed an energy barrier of 4.88 K. As another formation route of NH2CHO, solid-phase reactions have been investigated in laboratory experiments (e.g., Jones et al. 2011; Fedoseev et al. 2016; Dulieu et al. 2019; Martín-Doménech et al. 2020) and theoretical studies (e.g., Rimola et al. 2018; Enrique-Romero et al. 2019, 2022). For example, recent laboratory experiments showed that NH2CHO forms in H2O ice mixtures containing CO and NH3, irradiated by vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) photons (Chuang et al. 2022).

Recently, Lee et al. (2022) showed the spatial distribution of NH2CHO, HNCO, and H2CO, as well as other oxygen-bearing COMs, toward the atmosphere of the HH 212 protostellar disk. Although they found a similar abundance ratio as the star-forming regions studied in López-Sepulcre et al. (2019), they suggested that HNCO is likely formed in the gas phase and is a daughter molecule of NH2CHO. The spatial distribution of H2CO is more extended than that of NH2CHO, and the gas-phase formation of NH2CHO from the reaction between H2CO and NH2 is questionable from their observational data.

In contrast to the observational studies suggesting the chemical links between NH2CHO and HNCO, Quénard et al. (2018) suggested that hydrogenation reaction of HNCO is unlikely to produce NH2CHO on grain surfaces in their chemical models. They pointed out that the observed correlations between NH2CHO and HNCO may come from the fact that they react to temperature in the same manner rather than a chemical link between them. Noble et al. (2015) also demonstrated that the hydrogenation reaction of HNCO fails to produce NH2CHO efficiently in their laboratory experiments.

Gorai et al. (2020) analyzed data obtained with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) Band 4 toward the hot molecular core G10.47+0.03, and investigated the chemistry of molecules containing peptide-like bonds with chemical simulations. They found that HNCO and NH2CHO are linked by the gas-phase dual-cyclic hydrogenation addition and abstraction reactions. They also proposed that the main formation route of NH2CHO is the reaction between NH2 and H2CO in the warm-up and post-warm-up phases. If the findings of Gorai et al. (2020) are applicable to the general picture, we expect to find strong positive correlations between NH2CHO and HNCO and between NH2CHO and H2CO in other star-forming regions. Nazari et al. (2022) investigated the correlation between HNCO and NH2CHO using ALMA Band 6 data toward 37 high-mass sources with typical spatial resolutions of 0 5–1

5–1 5, corresponding to ∼1000–5000 au. Although they found a correlation between them (

5, corresponding to ∼1000–5000 au. Although they found a correlation between them (

In spite of several studies that have investigated the formation processes of NH2CHO in star-forming regions, it is still an open question. In this paper, we present observations of the NH2CHO, HNCO, H2CO, and CH3CN (13CH3CN) lines toward 30 high-mass star-forming regions covered by the "Digging into the Interior of Hot Cores with ALMA (DIHCA)" survey (Olguin et al. 2021, 2022). The typical angular resolution is 0 3. The source distances are between 1.3 and 5.26 kpc, resulting in linear resolutions of ∼520–1590 au. The data sets used in this paper are described in Section 2. Moment 0 maps of molecular lines and their analyses are presented in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, respectively. We discuss chemical relationships among NH2CHO, HNCO, and H2CO by statistical methods in Sections 4.1 and 4.2. The observed molecular abundances are compared with chemical models in Section 4.3. In Section 5, we summarize the main conclusions of this paper.

3. The source distances are between 1.3 and 5.26 kpc, resulting in linear resolutions of ∼520–1590 au. The data sets used in this paper are described in Section 2. Moment 0 maps of molecular lines and their analyses are presented in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, respectively. We discuss chemical relationships among NH2CHO, HNCO, and H2CO by statistical methods in Sections 4.1 and 4.2. The observed molecular abundances are compared with chemical models in Section 4.3. In Section 5, we summarize the main conclusions of this paper.

2. Observations

The 30 high-mass star-forming regions were observed by ALMA in band 6 (226.2 GHz, 1.33 mm) during cycles 4, 5, and 6 between 2016 and 2019 (Project IDs: 2016.1.01036.S, 2017.1.00237.S; PI: Sanhueza). Observations were performed using the 12 m array with a configuration similar to C40-5 and more than 40 antennas. The spectral configuration consists of four spectral windows of 1.8 GHz of width and a spectral resolution of 976

The observations were calibrated following the calibration procedure delivered by ALMA with CASA (CASA Team et al. 2022) versions 4.7.0, 4.7.2, 5.1.1-5, 5.4.0-70, and 5.6.1-8. The data were then self-calibrated in steps of decreasing solution time intervals. To obtain continuum-subtracted visibilities, we used the procedure from Olguin et al. (2021). Phase self-calibration was applied to the majority of the continuum-subtracted data sets to produce the data cubes. The data sets presented in this paper have angular resolutions of 0 3–0

3–0 4 with maximum recoverable scales between 8'' and 11''. The source selection criteria are as follows:

4 with maximum recoverable scales between 8'' and 11''. The source selection criteria are as follows:

- 1.The source has a flux density of >0.1 Jy at 230 GHz.

- 2.The source distance (d) is between 1.6 kpc and 3.8 kpc. However, as parallax distances have been made available over time, some of the observed targets resulted to be closer, 1.3 kpc, and farther, 5.26 kpc.

- 3.

Further details on the source properties can be found in K. Ishihara et al. (2023, in preparation).

The imaging of the data cubes from the continuum-subtracted visibilities was performed with the automasking routine YCLEAN (Contreras 2018; Contreras et al. 2018). As part of YCLEAN several calls to the CASA task tclean were performed with a multiscale deconvolver and Briggs weighting with a robust parameter of 0.5. The estimated absolute calibration flux error is 10%, according to the ALMA Proposer's User Guide. 9

3. Results and Analyses

3.1. Moment 0 Maps

We constructed moment 0 maps of molecular lines. At first, we checked the spectra around continuum cores within a single beam size in each high-mass star-forming region and confirmed the detection of each molecular species. Information on lines used in the moment 0 maps that were checked for detection is summarized in Table 1. These lines are not blended with other lines in most of the target regions.

Table 1. Information on Lines Used in Moment 0 Maps

| Species | Transition | Frequency | Eup/k | Binding Energy a | Binding Energy b | Binding Energy c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

( ) ) | (GHz) | (K) | (K) | (K) | (K) | |

| CH3CN | JK = 123 − 113 | 220.709017 | 133.16 | 4680 | 5906 | 4745–7652 |

| NH2CHO | 113,9 − 103,8 | 233.897318 | 94.16 | 5468 | 8104 | 5793–10,960 |

| HNCO | 100,10 − 90,9 | 219.798274 | 58.02 | 4684 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| H2CO | 32,2 − 22,1 | 218.475632 | 68.09 | 2050 | 5187 | 3071–6194 |

Notes.

a Values of binding energy were calculated by Gorai et al. (2020). b Values of binding energy were calculated for crystalline ice by Ferrero et al. (2020). c Values of binding energy were calculated for amorphous nature to mimic the interstellar water ice mantles by Ferrero et al. (2020).Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

We present moment 0 maps (contour maps) overlaid on the continuum map (gray scale) in Figure 1 as an example. Moment 0 maps toward all of the regions are presented in Figures 9(a)–(d) in Appendix A. Information on noise levels and contour levels of each map are summarized in Tables 8 and 9 in Appendix A.

Figure 1. Continuum images (gray scales) overlaid with contours indicating the moment 0 maps of molecular lines (left panel: white; CH3CN and cyan; H2CO, right panel: magenta; NH2CHO and yellow; HNCO) toward G10.62-0.38. Red crosses indicate the positions of hot molecular cores (HMCs) identified based on moment 0 maps of the CH3CN line. Information on noise levels and contour levels are summarized in Tables 8 and 9.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageEmission of CH3CN has been detected from all of the sources except for IRAS 18337-0743. In this source, no molecular lines have been detected. We therefore do not present the data toward this field in this paper. The detection rate of the CH3CN line is 96.7% ( ). We identified hot molecular cores (HMCs) based on the moment 0 maps of CH3CN. If two or more HMCs have been identified in a high-mass star-forming region, we labeled numbers for HMCs in order of integrated intensity, from the highest to the lowest. We identified 44 HMCs in total over the 29 high-mass star-forming regions.

). We identified hot molecular cores (HMCs) based on the moment 0 maps of CH3CN. If two or more HMCs have been identified in a high-mass star-forming region, we labeled numbers for HMCs in order of integrated intensity, from the highest to the lowest. We identified 44 HMCs in total over the 29 high-mass star-forming regions.

Emission of the H2CO and HNCO lines has been detected from all of the high-mass star-forming regions, except for IRAS 18337-0743. Emission of NH2CHO has been detected from 23 high-mass star-forming regions, and the detection rate is 76.7% ( ).

).

Moment 0 maps of all of the molecular lines show almost similar peaks, and they are usually consistent with the continuum peaks within the beam size. The continuum emission of Band 6 mainly comes from dust emission in most of the sources. The G5.89-0.37 region is more evolved and shows unique features in both continuum and moment 0 maps. The continuum emission in this region is dominated by the free–free emission, and shows an explosive dispersal event (Fernández-López et al. 2021). These results imply that molecules are enhanced in shock regions produced by the expanding motion.

Spatial distributions of NH2CHO are the most compact feature compared to the other species. This is expected, because the calculated binding energy of NH2CHO is the highest among the observed species (see Table 1). We will discuss this point further in Section 4.2.

3.2. Analyses

We have conducted line identification and analyzed molecular lines at HMCs with the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method assuming the thermodynamics equilibrium (LTE) assumption in the CASSIS software (Vastel et al. 2015). The positions of HMCs are indicated as red crosses in the moment 0 maps (Figures 9(a)–(d)), and their exact positions are summarized in Table 8. The upper level energies, Einstein coefficients, degeneracies, and partition functions are taken from the CDMS database (for 13CH3CN and CH3CN; Endres et al. 2016) and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) spectral line catalog (for NH2CHO, HNCO, H2CO; Pickett et al. 1998). The spectra were obtained within a single beam area.

In the line identification, we determined representative VLSR values at each core using the data of the CH3CN lines. We applied the representative VLSR when we identified the lines of the other species, which enables us to pin down molecular lines in line-rich HMCs.

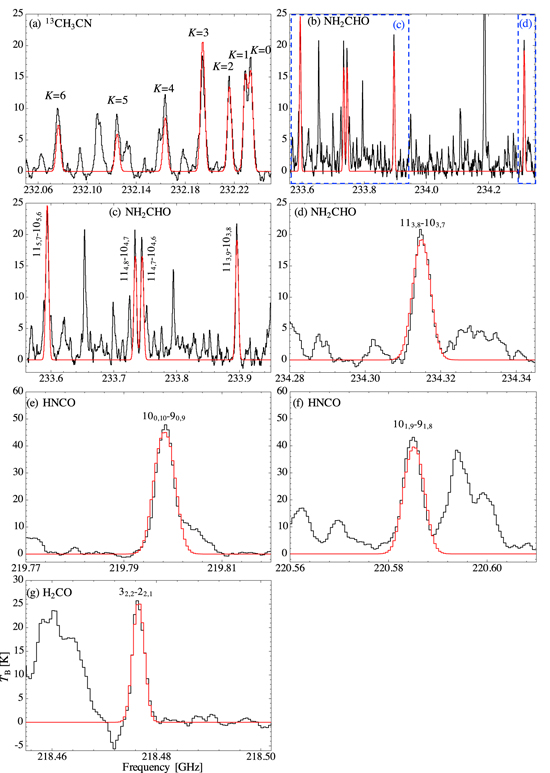

The column density (N), excitation temperature (Tex), line width (FWHM), and systemic velocity (VLSR) were treated as free parameters in the MCMC method. The size parameter was fixed, and then the beam filling factor was assumed to be one. We show the observed spectra (black curves) and the best-fitting model (red curves) toward the G10.62-0.38 HMC1 in Figure 2 as an example. We derived the excitation temperatures (Tex) and column densities of 13CH3CN by fitting its six K-ladder lines (JK

= 13K

− 12K

; K = 0 − 5, Eup/k = 78.0 − 256.9 K; see Table 2). We analyzed the 13CH3CN spectra, instead of CH3CN, because the low-K lines of the main isotopologue suffer from self absorption in some cases. The lines of 13CH3CN are found to be optically thin (

Figure 2. Spectra of molecular lines toward the G10.62-0.38 HMC1; (a) 13CH3CN, (b)–(d) NH2CHO (panels (c) and (d) are zoom-in spectra), (e) and (f) HNCO, and (g) H2CO. Black and red curves indicate the observed spectra and best-fitting model, respectively. The blue dotted squares in panel (b) indicate the regions for panels (c) and (d), respectively.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 2. Information on Lines Used in MCMC Analyses

| Species | Transition | Frequency | Eup/k | logAij |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (GHz) | (K) | ||

| 13CH3CN | JK = 130 − 120 | 232.234188 | 78.0 | −2.9667 |

| JK = 131 − 121 | 232.229822 | 85.2 | −2.9693 | |

| JK = 132 − 122 | 232.216726 | 106.7 | −2.9772 | |

| JK = 133 − 123 | 232.194906 | 142.4 | −2.9907 | |

| JK = 134 − 124 | 232.164369 | 192.5 | −3.0103 | |

| JK = 135 − 125 | 232.125130 | 256.9 | −3.0368 | |

| CH3CN | JK = 120 − 110 | 220.747261 | 68.9 | −3.0342 |

| JK = 121 − 111 | 220.743011 | 76.0 | −3.0372 | |

| JK = 122 − 112 | 220.730261 | 97.4 | −3.0465 | |

| JK = 123 − 113 | 220.709017 | 133.2 | −3.0624 | |

| JK = 124 − 114 | 220.679287 | 183.1 | −3.0857 | |

| NH2CHO | 113,8 − 103,7 | 234.316254 | 94.2 | −3.06215 |

| 113,9 − 103,8 | 233.897318 | 94.1 | −3.06449 | |

| 114,7 − 104,6 | 233.746504 | 114.9 | −3.09332 | |

| 114,8 − 104,7 | 233.735603 | 114.9 | −3.09334 | |

| 115,7 − 105,6 | 233.595412 | 141.7 | −3.13302 | |

| HNCO | 100,10 − 90,9 | 219.798320 | 58.0 | −3.82082 |

| 101,9 − 91,8 | 220.585200 | 101.5 | −3.82055 | |

| H2CO | 32,2 − 22,1 | 218.475632 | 68.1 | −3.80403 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

We converted the column densities of 13CH3CN to those of CH3CN using the following formula (Yan et al. 2019):

where DGC (in kpc units) is the distance from the Galactic Center. The DGC values are calculated from the galactic coordinate and the distance between the Sun and the Galactic center (8 kpc; Eisenhauer et al. 2003). We summarize the distance between the Sun and the target high-mass star-forming regions (D), DGC, and the calculated 12C/13C ratio in Tables 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows the relationships between DGC and the derived column density of CH3CN. The Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (

Figure 3. Relationships between the distance from the Galactic center (DGC) and the column density of CH3CN.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 3. Column Densities of Each Molecule Derived by the MCMC Method at Each Position

| Region | Position | Tex | N(13CH3CN) | 12C/13C | N(CH3CN) | N(NH2CHO) | N(HNCO) | N(H2CO) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (K) | (×1013 cm−2) | (×1014 cm−2) | (×1014 cm−2) | (×1014 cm−2) | (×1015 cm−2) | |||

| G10.62-0.38 | HMC1 | 202.0 (1.2) | 372 (37) | 28 | 1058 (106) | 170 (19) | 719 (72) | 60 (6) |

| HMC2 | 199.4 (0.4) | 213 (21) | 28 | 606 (61) | ⋯ | 78 (8) | 120 (12) | |

| G11.1-0.12 | HMC | 62.1 (0.3) | 7.2 (0.7) | 38 | 11 (1) | 9.7 (1.0) | 23 (2) | 13 (1) |

| G11.92-0.61 | HMC | 212.0 (0.05) | 590 (59) | 36 | 2125 (213) | 198 (22) | 919 (92) | 144 (50) |

| G14.22-0.50 S | HMC | 80.29 (0.03) | ⋯ | 43 | 9.2 (1.3) | 4.7 (0.5) | 19 (2) | 14.9 (1.5) |

| G24.60+0.08 | HMC | 104.9 (0.1) | ⋯ | 38 | 7.1 (1.2) | ⋯ | 20 (2) | 15.1 (1.5) |

| G29.96-0.02 | HMC | 270.4 (0.2) | 2510 (251) | 34 | 8489 (849) | 1591 (178) | 5687 (975) | 872 (90) |

| G333.12-0.56 | HMC1 | 193.6 (1.6) | 65 (7) | 39 | 250 (26) | 27 (3) | 110 (11) | 25 (2) |

| HMC2 | 73.3 (0.3) | 6.11(0.9) | 39 | 24 (3) | 9.6 (1.0) | 17 (2) | 8.9 (0.9) | |

| G333.23-0.06 | HMC1 | 199.99 (0.01) | 81 (11) | 33 | 263 (36) | 68 (7) | 289 (46) | 86 (9) |

| HMC2 | 100.2 (0.1) | 15 (5) | 33 | 49 (18) | 10.3 (1.6) | 35 (3) | 19 (2) | |

| G333.46-0.16 | HMC | 111 (6) | 19 (2) | 40 | 75 (8) | ⋯ | 9.4 (0.9) | 11 (1) |

| HMC1 | 150 (17) | 93 (11) | 40 | 371 (47) | 42 (4) | 119 (12) | 16 (6) | |

| HMC2 | 113.3 (0.2) | 9.0 (0.9) | 40 | 36 (4) | 13.0 (1.4) | 52 (5) | 25 (2) | |

| G335.579-0.272 | HMC | 249.7 (0.1) | 1055 (164) | 38 | 4047 (629) | 368 (40) | 999 (100) | ⋯ |

| G335.78+0.17 | HMC1 | 249.8 (0.1) | 172 (59) | 39 | 661 (229) | 214 (21) | 766 (90) | 168 (17) |

| HMC2 | 246 (2) | 119 (16) | 39 | 458 (98) | 86 (9) | 227 (30) | 83 (8) | |

| G336.01-0.82 | HMC | 218 (9) | 207 (22) | 39 | 803 (87) | 202 (20) | 619 (62) | ⋯ |

| G34.43+0.24 | HMC | 150.7 (0.3) | 852 (85) | 40 | 3385 (339) | 426 (47) | 1465 (158) | ⋯ |

| G34.43+0.24 MM2 | HMC | 116.6 (0.2) | 40 | 3.3 (0.3) | ⋯ | 3.25 (0.3) | 7.6 (0.8) | |

| G35.03+0.35A | HMC | 218 (16) | 78 (9) | 44 | 48 (8) | 64 (6) | 238 (66) | 97 (10) |

| G35.13-0.74 | HMC1 | 100 (1) | 54 (8) | 44 | 37 (4) | 41 (4) | 58 (21) | ⋯ |

| HMC2 | 175 (51) | ⋯ | 44 | 24 (9) | 10.9 (1.3) | 44 (4) | 24 (2) | |

| HMC3 | 92 (10) | ⋯ | 44 | 12.7 (1.5) | 7.5 (0.7) | 19 (2) | 14 (1) | |

| G35.20-0.74 N | HMC | 201.5 (0.7) | 127 (13) | 44 | 559 (56) | 145 (15) | 633 (63) | 133 (14) |

| G351.77-0.54 | HMC | 165.3 (0.2) | 943 (94) | 46 | 4336 (434) | 284 (28) | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| G5.89-0.37 | HMC1 | 104 (2) | 77 (8) | 37 | 286 (29) | ⋯ | 48 (5) | 101 (10) |

| HMC2 | 99.6 (0.2) | 33 (3) | 37 | 123 (12) | ⋯ | 94 (9) | 82 (8) | |

| G343.12-0.06 | HMC | 226 (16) | 441 (52) | 39 | 1710 (201) | 227 (91) | 1440 (196) | 403 (40) |

| IRAS 16562-3959 | HMC1 | 149 (3) | 246 (25) | 41 | 1008 (102) | 54 (5) | 403 (40) | 75 (44) |

| HMC2 | 88 (8) | 41 (4) | 41 | 169 (17) | 37 (4) | 266 (27) | 26 (3) | |

| IRAS 18089-1732 | HMC1 | 247 (21) | 1100 (141) | 41 | 4513 (578) | 470 (48) | 1646 (190) | 201 (20) |

| HMC2 | 79 (5) | 15 (2) | 41 | 62 (7) | 14.0 (1.4) | 39 (4) | 35 (3) | |

| IRAS 18151-1208 | HMC | 120 (14) | ⋯ | 38 | 12.9 (1.7) | ⋯ | 17 (2) | 36 (4) |

| IRAS 18182-1433 | HMC1 | 278 (15) | 567 (66) | 36 | 2022 (236) | 391 (93) | 1515 (154) | 327 (30) |

| HMC2 | 220.1 (0.7) | 120 (12) | 36 | 428 (43) | 40 (8) | 88 (17) | 48 (5) | |

| HMC3 | 138 (20) | 41 (6) | 36 | 145 (23) | ⋯ | 23 (2) | 13.2 (1.3) | |

| IRAS 18162-2048 | HMC | 94.3 (0.2) | ⋯ | 46 | 24 (3) | ⋯ | 50 (30) | 28 (3) |

| IRDC 18223-1243 | HMC | 102 (5) | ⋯ | 37 | 10.0 (1.1) | ⋯ | 15 (2) | 18 (2) |

| NGC6334I N | HMC1 | 176 (2) | 707 (71) | 46 | 3235 (324) | 203 (20) | 483 (179) | ⋯ |

| HMC2 | 200.7 (0.3) | ⋯ | 46 | 37 (10) | 195 (20) | 343 (122) | 150 (15) | |

| W33A | HMC | 199 (5) | 374 (39) | 40 | 1501 (154) | 405 (41) | 3031 (452) | 254 (25) |

Note. The numbers in parentheses indicate errors including the standard deviation derived from the MCMC analysis and the absolute flux calibration error of 10%.

A machine-readable version of the table is available.

Download table as: DataTypeset image

Table 4. Distances, Gas-to-dust Ratio, Flux Density, and H2 Column Density at Each Position

| Region | Position | D | DGC |

| Peak Flux | N(H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kpc) | (kpc) | (mJy beam−1) | (×1023 cm−2) | |||

| G10.62-0.38 | HMC1 | 4.95 | 3.26 | 53 | 134 | 22 (2) |

| HMC2 | 4.95 | 3.26 | 53 | 115 | 20 (2) | |

| G11.1-0.12 | HMC | 3.0 | 5.09 | 76 | 7 | 33 (0.3) |

| G11.92-0.61 | HMC | 3.37 | 4.75 | 71 | 71 | 8.6 (0.9) |

| G14.22-0.50 S | HMC | 1.9 | 6.17 | 95 | 25 | 11.3 (1.1) |

| G24.60+0.08 | HMC | 3.45 | 5.07 | 76 | 6 | 2.7 (0.3) |

| G29.96-0.02 | HMC | 5.26 | 4.33 | 66 | 96 | 15.0 (1.5) |

| G333.12-0.56 | HMC1 | 3.3 | 5.27 | 79 | 27 | 4.0 (0.4) |

| HMC2 | 3.3 | 5.27 | 79 | 14 | 5.9 (0.6) | |

| G333.23-0.06 | HMC1 | 5.2 | 4.09 | 63 | 30 | 3.4 (0.3) |

| HMC2 | 5.2 | 4.09 | 63 | 80 | 19 (2) | |

| G333.46-0.16 | HMC | 2.9 | 5.56 | 84 | 45 | 12.8 (1.3) |

| HMC1 | 2.9 | 5.56 | 84 | 42 | 8.8 (0.9) | |

| HMC2 | 2.9 | 5.56 | 84 | 7 | 1.7 (0.2) | |

| G335.579-0.272 | HMC | 3.25 | 5.22 | 78 | 274 | 31 (3) |

| G335.78+0.17 | HMC1 | 3.2 | 5.25 | 79 | 100 | 11.4 (1.1) |

| HMC2 | 3.2 | 5.25 | 79 | 30 | 3.5 (0.4) | |

| G336.01-0.82 | HMC | 3.1 | 5.32 | 80 | 40 | 5.4 (0.5) |

| G34.43+0.24 | HMC | 3.5 | 5.48 | 83 | 236 | 48 (5) |

| G34.43+0.24 MM2 | HMC | 3.5 | 5.48 | 83 | 16 | 4.2 (0.4) |

| G35.03+0.35A | HMC | 2.32 | 6.24 | 96 | 33 | 5.2 (0.5) |

| G35.13-0.74 | HMC1 | 2.2 | 6.33 | 98 | 40 | 14.6 (1.5) |

| HMC2 | 2.2 | 6.33 | 98 | 29 | 5.9 (0.6) | |

| HMC3 | 2.2 | 6.33 | 98 | 8 | 3.0 (0.3) | |

| G35.20-0.74 N | HMC | 2.19 | 6.34 | 98 | 77 | 13.7 (1.4) |

| G351.77-0.54 | HMC | 1.3 | 6.72 | 106 | 158 | 37 (4) |

| G5.89-0.37 | HMC1 | 2.99 | 5.04 | 76 | 54 | 14.7 (1.5) |

| HMC2 | 2.99 | 5.04 | 76 | 14 | 3.9 (0.4) | |

| G343.12-0.06 | HMC | 2.9 | 5.29 | 80 | 168 | 22 (0.2) |

| IRAS 16562-3959 | HMC1 | 2.38 | 5.73 | 87 | 10 | 4.0 (0.4) |

| HMC2 | 2.38 | 5.73 | 87 | 155 | 102 (10) | |

| IRAS 18089-1732 | HMC1 | 2.34 | 5.74 | 87 | 157 | 20 (2) |

| HMC2 | 2.34 | 5.74 | 87 | 26 | 11 (1) | |

| IRAS 18151-1208 | HMC | 3 .0 | 5.24 | 79 | 8 | 3.5 (0.4) |

| IRAS 18182-1433 | HMC1 | 3.58 | 4.68 | 70 | 21 | 3.4 (0.3) |

| HMC2 | 3.58 | 4.68 | 70 | 23 | 4.8 (0.5) | |

| HMC3 | 3.58 | 4.68 | 70 | 32 | 11 (1) | |

| IRAS 18162-2048 | HMC | 1.3 | 6.73 | 106 | 319 | 134 (13) |

| IRDC 18223-1243 | HMC | 3.4 | 4.90 | 73 | 7 | 3.3 (0.3) |

| NGC6334I | HMC1 | 1.35 | 6.67 | 105 | 266 | 121 (12) |

| HMC2 | 1.35 | 6.67 | 105 | 635 | 290 (29) | |

| NGC6334I N | HMC1 | 1.35 | 6.67 | 105 | 141 | 55(5) |

| HMC2 | 1.35 | 6.67 | 105 | 34 | 11 (1) | |

| W33A | HMC | 2.53 | 5.56 | 84 | 50 | 7.7 (0.8) |

Note. The numbers in parentheses indicate errors calculated from the absolute flux calibration error of 10%.

A machine-readable version of the table is available.

Download table as: DataTypeset image

The excitation temperature derived from 13CH3CN or CH3CN is known to be a good thermometer (e.g., Hernández-Hernández et al. 2014; Hunter et al. 2014). In the case of the other species, several lines (see Table 2) with similar upper-state energies have been clearly detected, and it is difficult to determine their excitation temperatures and column densities simultaneously by fitting their lines. We then applied the values of excitation temperature derived from the analyses of 13CH3CN or CH3CN. We checked the spectra at all of the positions and selected lines that can be clearly identified and are not affected by contamination by other lines in most positions. 10 Table 2 summarizes information on lines used in the MCMC method. If the lines of the target species do not show the single Gaussian feature (e.g., possible contamination with other lines), we excluded them from the fitting to derive their column densities precisely. The derived column densities and excitation temperatures are summarized in Table 3. Assuming isothermal gas and using the excitation temperature derived from 13CH3CN or CH3CN, we found all other lines to be optically thin. The results of VLSR and FWHM derived by the MCMC method are summarized in Table 10 in Appendix B.

We derived the column densities of H2, N(H2), from the continuum data using the following formula (e.g., Sabatini et al. 2022):

where F1.3mm,  , and mH are the continuum peak flux at 1.3 mm, the gas-to-dust ratio, the Planck function at 1.3 mm with a dust temperature, the beam solid angle, the H2 mean molecular weight (2.8), and the mass of the hydrogen atom, respectively. We adopted a value of

, and mH are the continuum peak flux at 1.3 mm, the gas-to-dust ratio, the Planck function at 1.3 mm with a dust temperature, the beam solid angle, the H2 mean molecular weight (2.8), and the mass of the hydrogen atom, respectively. We adopted a value of

The continuum peak flux, gas-to-dust ratios, and derived H2 column densities are summarized in Table 4.

4. Discussion

4.1. Correlation Among Each Species

We search for correlations among the observed species to investigate their chemical links. As mentioned in Section 1, NH2CHO has been considered to be closely chemically linked with HNCO (e.g., López-Sepulcre et al. 2015, 2019). In addition, chemical simulations suggest gas-phase formation of NH2CHO from H2CO in hot core regions (Gorai et al. 2020). On the other hand, CH3CN is not expected to be directly related to the other observed species.

We use abundances derived as X(a) = N(a)/N(H2), where a represents the molecular species, because comparisons using the column densities may mislead correlation coefficients. If we investigate correlations using column densities, the total gas mass or total gas column density represented by N(H2) could be the lurking third variable. We made plots to investigate this possibility as shown in Figure 4. The outliers, labeled as "IRAS 16562-3959 HMC2" and "IRAS 18162-2048," show lower molecular column densities; nevertheless they have the highest H2 column densities. IRAS 16562-3959 HMC2 is an ultracompact H II (UC H II) region (Guzmán et al. 2018; Taniguchi et al. 2020). IRAS 18162-2048 possesses a highly collimated magnetized radio jet (Carrasco-González et al. 2010). This jet may produce UV radiation via the strong shocks (Girart et al. 2017). Thus, the lower molecular column densities in these two sources are likely caused by destruction of molecules by the UV radiation.

Figure 4. Relationships between the H2 column density and molecular column densities.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWe conducted the Spearman's correlation coefficient test, and the derived p-values and correlation coefficients (

Table 5. Molecular Abundances

| Region | Position | X(CH3CN) | X(NH2CHO) | X(HNCO) | X(H2CO) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G10.62-0.38 | HMC1 | (4.7 ± 0.7) × 10−8 | (7.5 ± 1.1) × 10−9 | (3.2 ± 0.4) × 10−8 | (2.7 ± 0.4) × 10−8 |

| HMC2 | (3.1 ± 0.4) × 10−8 | ⋯ | (3.9 ± 0.6) × 10−9 | (6.1 ± 0.7) × 10−8 | |

| G11.1-0.12 | HMC | (3.2 ± 0.5) × 10−9 | (3.0 ± 0.4) × 10−9 | (7.1 ± 1.0) × 10−9 | (3.9 ± 0.6) × 10−8 |

| G11.92-0.61 | HMC | (2.5 ± 0.3) × 10−7 | (2.3 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | (1.1 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | (1.7 ± 0.6) × 10−7 |

| G14.22-0.50 S | HMC | (8.1 ± 1.4) × 10−10 | (4.2 ± 0.6) × 10−10 | (1.7 ± 0.2) × 10−9 | (1.3 ± 0.2) × 10−8 |

| G24.60+0.08 | HMC | (2.6 ± 0.5) × 10−9 | ⋯ | (7.3 ± 1.0) × 10−9 | (5.6 ± 0.8) × 10−8 |

| G29.96-0.02 | HMC | (5.7 ± 0.8) × 10−7 | (1.1 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | (3.8 ± 0.8) × 10−7 | (5.8 ± 0.8) × 10−7 |

| G333.12-0.56 | HMC1 | (6.3 ± 0.9) × 10−8 | (6.8 ± 1.0) × 10−9 | (2.8 ± 0.4) × 10−8 | (6.2 ± 0.9) × 10−8 |

| HMC2 | (4.0 ± 0.7) × 10−9 | (1.6 ± 0.2) × 10−9 | (2.9 ± 0.4) × 10−9 | (1.5 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | |

| G333.23-0.06 | HMC1 | (7.8 ± 1.3) × 10−8 | (2.0 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | (8.6 ± 1.6) × 10−8 | (2.6 ± 0.4) × 10−7 |

| HMC2 | (2.6 ± 1.0) × 10−9 | (5.6 ± 1.0) × 10−10 | (1.9 ± 0.3) × 10−9 | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 10−8 | |

| G333.46-0.16 | HMC | (5.9 ± 0.8) × 10−9 | ⋯ | (7.3 ± 1.0) × 10−10 | (8.4 ± 1.2) × 10−9 |

| HMC1 | (4.2 ± 0.7) × 10−8 | (4.8 ± 0.7) × 10−9 | (1.4 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | (1.8 ± 0.7) × 10−8 | |

| HMC2 | (2.1 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | (7.6 ± 1.1) × 10−9 | (3.0 ± 0.4) × 10−8 | (1.4 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | |

| G335.579-0.272 | HMC | (1.3 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | (1.2 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | (3.2 ± 0.5) × 10−8 | ⋯ |

| G335.78+0.17 | HMC1 | (5.8 ± 2.0) × 10−8 | (1.9 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | (6.7 ± 1.0) × 10−8 | (1.5 ± 0.2) × 10−7 |

| HMC2 | (1.3 ± 0.3) × 10−7 | (2.4 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | (6.4 ± 1.1) × 10−8 | (2.4 ± 0.3) × 10−7 | |

| G336.01-0.82 | HMC | (1.5 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | (3.8 ± 0.5) × 10−8 | (1.2 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | ⋯ |

| G34.43+0.24 | HMC | (7.1 ± 1.0) × 10−8 | (9.0 ± 1.3) × 10−9 | (3.1 ± 0.5) × 10−8 | ⋯ |

| G34.43+0.24 MM2 | HMC | (8.0 ± 1.1) × 10−10 | ⋯ | (7.8 ± 1.1) × 10−10 | (1.8 ± 0.3) × 10−8 |

| G35.03+0.35A | HMC | (9.1 ± 1.7) × 10−9 | (1.2 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | (4.6 ± 1.3) × 10−8 | (1.9 ± 0.3) × 10−7 |

| G35.13-0.74 | HMC1 | (2.6 ± 0.4) × 10−9 | (2.8 ± 0.4) × 10−9 | (4.0 ± 1.5) × 10−9 | ⋯ |

| HMC2 | (4.1 ± 1.6) × 10−9 | (1.9 ± 0.3) × 10−9 | (7.5 ± 1.1) × 10−9 | (4.1 ± 0.6) × 10−8 | |

| HMC3 | (4.2 ± 0.7) × 10−9 | (2.5 ± 0.4) × 10−9 | (6.3 ± 0.9) × 10−9 | (4.7 ± 0.7) × 10−8 | |

| G35.20-0.74 N | HMC | (4.1 ± 0.6) × 10−8 | (1.1 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | (4.6 ± 0.7) × 10−8 | (9.7 ± 1.4) × 10−8 |

| G351.77-0.54 | HMC | (1.2 ± 0.3) × 10−7 | (7.7 ± 1.1) × 10−9 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| G5.89-0.37 | HMC1 | (2.0 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | ⋯ | (3.2 ± 0.5) × 10−9 | (6.9 ± 1.0) × 10−8 |

| HMC2 | (3.2 ± 0.5) × 10−8 | ⋯ | (2.4 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | (2.1 ± 0.3) × 10−7 | |

| G343.12-0.06 | HMC | (8.0 ± 1.2) × 10−8 | (1.1 ± 0.4) × 10−8 | (6.7 ± 1.1) × 10−8 | (1.9 ± 0.3) × 10−7 |

| IRAS 16562-3959 | HMC1 | (2.5 ± 0.4) × 10−7 | (1.3 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 10−7 | (1.9 ± 1.1) × 10−7 |

| HMC2 | (1.7 ± 0.2) × 10−9 | (3.6 ± 0.5) × 10−10 | (2.6 ± 0.4) × 10−9 | (2.6 ± 0.4) × 10−9 | |

| IRAS 18089-1732 | HMC1 | (2.3 ± 0.4) × 10−7 | (2.3 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | (8.2 ± 1.3) × 10−8 | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 10−7 |

| HMC2 | (5.8 ± 0.8) × 10−9 | (1.3 ± 0.2) × 10−9 | (3.6 ± 0.5) × 10−9 | (3.2 ± 0.5) × 10−8 | |

| IRAS 18151-1208 | HMC | (3.7 ± 0.6 × 10−9 | ⋯ | (4.9 ± 0.7) × 10−9 | (1.0 ± 0.2) × 10−7 |

| IRAS 18182-1433 | HMC1 | (5.9 ± 0.9) × 10−7 | (1.1 ± 0.3) × 10−7 | (4.4 ± 0.6) × 10−7 | (9.5 ± 1.4) × 10−7 |

| HMC2 | (9.0 ± 1.3) × 10−8 | (8.3 ± 1.8) × 10−9 | (1.8 ± 0.4) × 10−8 | (1.0 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | |

| HMC3 | (1.4 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | ⋯ | (2.2 ± 0.3) × 10−9 | (1.3 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | |

| IRAS 18162-2048 | HMC | (1.8 ± 0.3) × 10−10 | ⋯ | (3.7 ± 2.3) × 10−10 | (2.1 ± 0.3) × 10−9 |

| IRDC 18223-1243 | HMC | (3.0 ± 0.4) × 10−9 | ⋯ | (4.6 ± 0.6) × 10−9 | (5.4 ± 0.8) × 10−8 |

| NGC6334I N | HMC1 | (5.9 ± 0.8) × 10−8 | (3.7 ± 0.5) × 10−9 | (8.8 ± 3.4) × 10−9 | |

| HMC2 | (3.3 ± 1.0) × 10−9 | (1.7 ± 0.2) × 10−8 | (3.0 ± 1.1) × 10−8 | (1.3 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | |

| W33A | HMC | (2.0 ± 0.2) × 10−7 | (5.3 ± 0.7) × 10−8 | (4.0 ± 0.6) × 10−7 | (3.3 ± 0.5) × 10−7 |

Note. Errors include the standard deviation derived from the MCMC analysis and the absolute flux calibration error of 10%.

A machine-readable version of the table is available.

Download table as: DataTypeset image

Figure 5 shows relationships between each pair of molecular species. We conducted the Spearman's rank correlation test for each pair. The Spearman's correlation coefficients (

Figure 5. Relationships of molecular abundances. The red lines in the top two panels show the result of the best power-law fit.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWe fitted the plot of NH2CHO versus HNCO, as López-Sepulcre et al. (2015) analyzed. The best power-law fit is X(NH2CHO) = 0.07X(HNCO)0.92(±0.08). López-Sepulcre et al. (2015) derived the best power-law fit as X(NH2CHO) = 0.04X(HNCO)0.93, using data toward YSOs with various stellar masses, from low- through intermediate- to high-mass stars. Our result agrees with that derived by López-Sepulcre et al. (2015) well. Our data set contains a sample of targets with larger abundances of NH2CHO (≈3 × 10−10 − 10−7) than those in López-Sepulcre et al. (2015; ≈3 × 10−11 − 10−8), and our sample is the largest one in high-mass star-forming regions, to our best knowledge. The same best power-law fits for different ranges of abundances likely mean that the chemistry (formation and destruction processes) of NH2CHO is common around YSOs with various stellar masses.

As we found a tight correlation between NH2CHO and H2CO, we also fitted the plot of NH2CHO versus H2CO with the same method. The best power-law fit is X(NH2CHO) = 0.35X(H2CO)1.07(±0.09).

The second and third rows of Figure 5 show correlations between CH3CN and NH2CHO/HNCO/H2CO. Although there are no expected direct chemical relationships between CH3CN and the other species, there is a possibility that CH3CN is positively correlated with the other species. The plots show more scatter compared to the two plots in the first row, suggestive of weaker correlations. The Spearman's correlation coefficients are derived to be 0.83, 0.85, and 0.74 for pairs of CH3CN–NH2CHO, CH3CN–HNCO, and CH3CN–H2CO, respectively. These correlation coefficients are lower than those for pairs NH2CHO–HNCO and NH2CHO–H2CO, but they still indicate strong correlations (

4.2. Partial Correlation Test

As we derived in Section 4.1, all of the species show positive correlations. However, as Quénard et al. (2018) pointed out, the observed correlations may not indicate chemical links, but they could reflect that all of the species act similarly against temperature. For example, assuming that molecules form on dust surfaces in the cold starless core stage and sublimate into the gas phase in the hot core regions with temperatures above 100 K, their abundances increase as the temperature increases. In this subsection, we will conduct a partial correlation test to investigate pure chemical links excluding the effect of temperature.

Figure 6 shows relationships between excitation temperatures and molecular abundances. We found that all of the molecular abundances show positive correlations with the excitation temperatures;

Figure 6. Relationships between excitation temperatures and molecular abundances.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn order to derive the pure chemical links excluding the lurking third variable, or the temperature, we conducted a partial correlation test. Assuming the local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE), we use the excitation temperature derived from CH3CN analyses to represent the gas kinetic temperature and dust temperature. The partial correlation test removes the mutual dependence of the two first variables on the third one. We utilize the excitation temperature derived from the analyses of the CH3CN (13CH3CN) lines as a representative temperature. We adopted the first-order partial correlation coefficient (e.g., Wall & Jenkins 2012; Urquhart et al. 2018):

Here, we are interested in molecular abundances (1 and 2), and the temperature is considered as the third variable (3).

Table 6 summarizes all of the correlation coefficients for each pair of molecules. The derived partial correlation coefficients are summarized in the last row.

Table 6. Summary of Partial Correlation Coefficient

| HNCO versus NH2CHO | H2CO versus NH2CHO | CH3CN versus HNCO | CH3CN versus NH2CHO | H2CO versus CH3CN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.74 |

|

| 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.67 |

|

| 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.76 |

|

| 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.48 |

Note. "1" and "2" correspond to Species A and Species B, respectively (Species A versus Species B written at the top of table). "3" corresponds to the excitation temperature.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

The partial correlation coefficients for HNCO–NH2CHO and H2CO–NH2CHO are still high (>0.8), whereas those for the other pairs with CH3CN become lower (<0.65). These results most likely indicate that NH2CHO is chemically linked with HNCO and H2CO. Thus, the observed correlation between NH2CHO and HNCO is not the result of having the same response of the two species to temperature, as pointed out by Quénard et al. (2018). On the other hand, CH3CN is less chemically linked with the other species studied here. We found that the partial correlation test is a strong tool to statistically investigate chemical relationships.

We further investigated the correlation coefficients between the molecular abundances and excitation temperatures. The highest correlation coefficient is derived for NH2CHO (0.81), followed by HNCO (0.78), CH3CN (0.76), and H2CO (0.67). This order matches with the order of the calculated binding energies of each species (Table 1). This also suggests that thermal desorption is important for these molecules. As the emission of a molecule with a high binding energy should be dominated by the central hot core region, the correlation with the temperature should be strong. Hence, the derived correlation coefficients with the temperature suggest that the NH2CHO emission comes from the central hot core region, whereas the emission of H2CO could come not only from the inner hot core but also from the outer part of cores. This is consistent with the spatial distribution of the molecular lines (Figures 9(a)–(d)), as mentioned in Section 3.1.

4.3. Comparison with Chemical Models

We compare the observed molecular abundances with the chemical models developed by Gorai et al. (2020). We consider a linear density variation with a slope  , where tf − ti corresponds to the collapse timescale. Similarly, the temperature increases with a linear slope during the warm-up stage.

, where tf − ti corresponds to the collapse timescale. Similarly, the temperature increases with a linear slope during the warm-up stage.

The dual-cyclic hydrogen addition and abstraction reactions (Haupa et al. 2019) that occur in the gas phase are included in the models. This cycle consists of four reactions. From HNCO to NH2CHO, two hydrogen addition reactions occur:

followed by

In a sequence from NH2CHO to HNCO, two hydrogen abstraction reactions happen:

followed by

Reactions (6) and (8) are barrierless, whereas Reactions (5) and (7) have activation barriers of 2530–5050 K and 240–3130 K, respectively. In the models of Gorai et al. (2020), the gas-phase reaction between NH2 and H2CO to form NH2CHO is included:

The hydrogenation reaction leads to the formation of CH3CN on dust surfaces in the cold phase. In contrast, its formation by a dust-surface radical–radical reaction between CN and CH3 is efficient during the initial warm-up phase. In addition, CH3CN could form by the following barrierless reaction on dust surfaces:

The major gas-phase formation route of CH3CN is the dissociative recombination reaction of CH3CNH+. Destruction routes of CH3CN on dust surfaces are cosmic-ray-induced desorption, photodissociation, and thermal and nonthermal desorption. Furthermore, the models of Gorai et al. (2020) include the successive hydrogenation reactions of CH3CN to lead finally to ethanimine (CH3CHNH).

There are six physical parameters in the models of Gorai et al. (2020); the maximum density ( [cm−3]), maximum temperature (

[cm−3]), maximum temperature ( [K]), collapsing timescale (tcoll [yr]), warm-up timescale (tw [yr]), post-warm-up timescale (tpw [yr]), and initial dust temperature (Tice [K]). Gorai et al. (2020) ran two types of models, Model A and Model B, as summarized in Table 9 in their paper. In Model A, the physical parameters are fixed with the following values;

[K]), collapsing timescale (tcoll [yr]), warm-up timescale (tw [yr]), post-warm-up timescale (tpw [yr]), and initial dust temperature (Tice [K]). Gorai et al. (2020) ran two types of models, Model A and Model B, as summarized in Table 9 in their paper. In Model A, the physical parameters are fixed with the following values;  cm−3,

cm−3,  K, tcoll = 106 yr, tw = 5 × 104 yr, tpw = (6.2–10) × 104 yr, and Tice = 20 K. For Model B,

K, tcoll = 106 yr, tw = 5 × 104 yr, tpw = (6.2–10) × 104 yr, and Tice = 20 K. For Model B,  ,

,  , and tcoll varied in ranges of 105–107 cm−3, 100 − 400 K, and 105–106 yr, respectively. The warm-up timescale, post-warm-up timescale, and initial dust temperatures were fixed at 5 × 104 yr, 105 yr, and 20 K, respectively, in Model B.

, and tcoll varied in ranges of 105–107 cm−3, 100 − 400 K, and 105–106 yr, respectively. The warm-up timescale, post-warm-up timescale, and initial dust temperatures were fixed at 5 × 104 yr, 105 yr, and 20 K, respectively, in Model B.

Figure 7 shows comparisons between the observed abundances and the modeled abundances obtained by Model A (Gorai et al. 2020). As the observed values, we plot the four representative values from the whole hot core populations; maximum, average, median, and minimum values (Table 7).

Figure 7. Comparison with Model A (Gorai et al. 2020). Panels (a)–(d) show results of HNCO, NH2CHO, H2CO, and CH3CN, respectively. Black curves indicate the modeled abundances (gas phase). The four representative observed abundances are plotted (Maximum, Average, Median, and Minimum). The blue filled ranges indicate the ranges between average and median values.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 7. Summary of Representative Observed Abundances

| HNCO | NH2CHO | H2CO | CH3CN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum (Min) | 3.70 × 10−10 | 3.59 × 10−10 | 2.09 × 10−9 | 1.77 × 10−10 |

| Maximum (Max) | 4.42 × 10−7 | 1.14 × 10−7 | 9.54 × 10−7 | 5.90 × 10−7 |

| Average (Ave.) | 5.64 × 10−8 | 1.77 × 10−8 | 1.31 × 10−7 | 8.11 × 10−8 |

| Median (Med.) | 2.13 × 10−8 | 8.61 × 10−9 | 6.52 × 10−8 | 3.13 × 10−8 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

The minimum abundances agree with the model around 1.02 × 106 yr (T ≈ 100 K). The minimum observed CH3CN abundance agrees with model at the almost same age within a factor of 1.3. The minimum abundance of NH2CHO is derived at IRAS 16562-3959 HMC2, and those of HNCO and H2CO are derived in IRAS 18162-2048. The derived excitation temperatures of CH3CN in these HMCs are 88 K and 94.3 K, which are lower than the other sources and close to the modeled value of 100 K. In addition, in the case of IRAS 18162-2048, as mentioned before, the ionized jet may explain the lower molecular column densities.

The observed average and median abundances of HNCO and NH2CHO are most close to the modeled values around (≈1.04–1.05) × 106 yr (T ≈ 165–200 K). The temperature ranges that can reproduce the observed average and median values agree with the average excitation temperature at the whole hot core populations (≈162 K). Thus, the tendencies of the observed abundances for both HNCO and NH2CHO agree with the modeled results. The median value of H2CO is close to the modeled abundance around ≈1.03 × 106 yr, which is almost consistent with the ages constrained by HNCO and NH2CHO ((≈1.04–1.05)×106 yr), but in general, the modeled H2CO abundances tend to be lower than the observed ones. The observed maximum abundances cannot be explained by Model A, implying that assumed physical parameters are not suitable for the hot core with the maximum molecular abundances.

Figure 8 shows a comparison between the representative observed abundances and modeled abundances obtained by Model B (Gorai et al. 2020). The left panels show the dependences on different tcoll and  , and the right panels show the dependences on different tcoll and

, and the right panels show the dependences on different tcoll and  , respectively. The initial dust temperature (Tice) is fixed at 20 K, and tpw is 105 yr. The modeled abundances plotted here are the values at the end of the simulations; t = tcollapse + twarm−up (5×104 yr)+ tpost warm−up (105 yr). As seen in Figure 8, the maximum observed abundances could not be reproduced by the models in most cases, because the plotted modeled abundances are the values at the end of the simulation. We show the modeled maximum abundances obtained by Model B in Figure 10 in Appendix C. The modeled maximum abundances with some cases consist with the observed maximum abundances by less than 1 order of magnitude.

, respectively. The initial dust temperature (Tice) is fixed at 20 K, and tpw is 105 yr. The modeled abundances plotted here are the values at the end of the simulations; t = tcollapse + twarm−up (5×104 yr)+ tpost warm−up (105 yr). As seen in Figure 8, the maximum observed abundances could not be reproduced by the models in most cases, because the plotted modeled abundances are the values at the end of the simulation. We show the modeled maximum abundances obtained by Model B in Figure 10 in Appendix C. The modeled maximum abundances with some cases consist with the observed maximum abundances by less than 1 order of magnitude.

Figure 8. Comparison with Model B (Gorai et al. 2020). The panels from top to bottom show the results of HNCO, NH2CHO, H2CO, and CH3CN, respectively. The modeled abundances plotted here are the values at the end of the simulations; t = tcollapse + twarm−up (5 × 104 yr)+ tpost warm−up (105 yr). The left panels show the dependences on different collapsing timescales and maximum densities with a maximum temperature of 200 K. The right panels show the dependences on different collapsing timescales and maximum temperatures with a maximum density of 107 cm−3. The four representative observed abundances are plotted (Maximum, Average, Median, and Minimum). The blue filled ranges indicate the ranges between average and median values.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn Figure 8, we found low abundances of H2CO and high abundances of NH2CHO in the models. We attribute these results to the uncertainty of the reaction rate coefficient for the gas-phase reaction between NH2 and H2CO (Reaction (9)). We used an

The maximum abundances of HNCO and NH2CHO can be reproduced by the models with  cm−3, as seen in the left panels. The average and median abundances of these two species agree with the following three models; (1)

cm−3, as seen in the left panels. The average and median abundances of these two species agree with the following three models; (1)  cm−3 and tcoll ≈ 8 × 105 yr, (2)

cm−3 and tcoll ≈ 8 × 105 yr, (2)  cm−3 and tcoll = 4 × 105 yr, and (3)

cm−3 and tcoll = 4 × 105 yr, and (3)  cm−3 and tcoll = 2 × 105 yr. The models with higher

cm−3 and tcoll = 2 × 105 yr. The models with higher  values need to collapse rapidly to reproduce the observed abundances. Their minimum abundances cannot be reproduced by the models, because the adopted maximum temperature (200 K) is too high for these sources (88–95 K; see in the previous paragraph). In fact, the minimum abundances can be reproduced by the model with

values need to collapse rapidly to reproduce the observed abundances. Their minimum abundances cannot be reproduced by the models, because the adopted maximum temperature (200 K) is too high for these sources (88–95 K; see in the previous paragraph). In fact, the minimum abundances can be reproduced by the model with  K in the right panels, as discussed later.

K in the right panels, as discussed later.

The minimum H2CO abundance is reproduced by the models with  cm−3, while the average and median values agree with the model with

cm−3, while the average and median values agree with the model with  cm−3. In addition, the models with

cm−3. In addition, the models with  cm−3 and 106 cm−3 reproduce the average and median abundances around tcoll ≈ (1–2) × 105 yr. The observational results of H2CO tend to show agreements with lower-

cm−3 and 106 cm−3 reproduce the average and median abundances around tcoll ≈ (1–2) × 105 yr. The observational results of H2CO tend to show agreements with lower- models compared to the cases of HNCO and NH2CHO (

models compared to the cases of HNCO and NH2CHO ( cm−3). These results would be consistent with the fact that the H2CO emission shows more spatially extended features than the other molecules (Figures 9(a)–(d) in Appendix A). The maximum value, derived in IRAS 18182-1433 HMC1, has not been reproduced by the models in Figure 8, but the modeled maximum abundances with

cm−3). These results would be consistent with the fact that the H2CO emission shows more spatially extended features than the other molecules (Figures 9(a)–(d) in Appendix A). The maximum value, derived in IRAS 18182-1433 HMC1, has not been reproduced by the models in Figure 8, but the modeled maximum abundances with  cm−3 agree with the observed maximum value within 1 order of magnitude (see Figure 10 in Appendix C).

cm−3 agree with the observed maximum value within 1 order of magnitude (see Figure 10 in Appendix C).

As seen in the right panels of HNCO and NH2CHO in Figure 8, the maximum abundances prefer shorter collapsing time with a highest  of 400 K. The maximum abundances of the both molecules are derived in IRAS 18182-1433 HMC1. The excitation temperature at HMC1 is the highest value (≈278 K) among the observed hot cores. This is consistent with the agreement of the maximum abundance with the highest

of 400 K. The maximum abundances of the both molecules are derived in IRAS 18182-1433 HMC1. The excitation temperature at HMC1 is the highest value (≈278 K) among the observed hot cores. This is consistent with the agreement of the maximum abundance with the highest  model. On the other hand, HMC2 and HMC3 in the same region do not show high abundances, and NH2CHO has not been detected at HMC3. Hence, in this high-mass star-forming region, it is likely that an massive young stellar object (MYSO) in HMC1 was first born rapidly, and the other sources were slowly formed later.

model. On the other hand, HMC2 and HMC3 in the same region do not show high abundances, and NH2CHO has not been detected at HMC3. Hence, in this high-mass star-forming region, it is likely that an massive young stellar object (MYSO) in HMC1 was first born rapidly, and the other sources were slowly formed later.

The average and median values of HNCO and NH2CHO are consistent with the models with  K. The best agreed conditions are tcoll = (2–3) × 105 yr, and the models with lower

K. The best agreed conditions are tcoll = (2–3) × 105 yr, and the models with lower  values need to collapse quickly.

values need to collapse quickly.

In the case of H2CO, the minimum observed abundance agrees with the models within 1 order of magnitude except for  K, but the other three representative values disagree with the models. This could be explained by the fact that the observed H2CO abundances prefer the models with low-

K, but the other three representative values disagree with the models. This could be explained by the fact that the observed H2CO abundances prefer the models with low- values, while the right panels show results with

values, while the right panels show results with  cm−3.

cm−3.

The observed CH3CN abundances disagree in most cases, but CH3CN does not take part in the formation network of NH2CHO. This disagreement does not undermine our analysis for NH2CHO. The minimum value agrees with the models of  K and tcoll ≈ (3–6) × 105 yr within 1 order of magnitude. As seen in Figure 10 in Appendix C, the observed CH3CN abundances agree with the modeled maximum abundances with low-

K and tcoll ≈ (3–6) × 105 yr within 1 order of magnitude. As seen in Figure 10 in Appendix C, the observed CH3CN abundances agree with the modeled maximum abundances with low- models (105 − 105.5 cm−3), not at the end of the simulations. This could mean that CH3CN is deficient at the age of the end of the simulations due to its destruction, and the CH3CN gas may trace chemically younger gas around MYSOs.

models (105 − 105.5 cm−3), not at the end of the simulations. This could mean that CH3CN is deficient at the age of the end of the simulations due to its destruction, and the CH3CN gas may trace chemically younger gas around MYSOs.

We note that there are still uncertainties in the reaction rate constants for the dual-cyclic hydrogen addition and abstraction reactions. We tested changing the

In summary, most of the sources observed by the DIHCA project are at the hot core stage with temperatures of 150–400 K and densities of 106–107 cm−3, judging from HNCO and NH2CHO. These values are consistent with typical hot core values. On the other hand, the observed H2CO and CH3CN abundances prefer models with lower density conditions of ∼105–105.5 cm−3. This is consistent with the spatial distribution of the observed emission. Thus, the contribution from the outer parts of cores is larger in the case of H2CO and CH3CN, while NH2CHO and HNCO emission comes from inner central cores. These are consistent with the expectation based on the calculated binding energy as discussed in Section 4.2.

5. Conclusions

We have analyzed molecular lines of NH2CHO, HNCO, H2CO, and CH3CN (13CH3CN) toward the 30 high-mass star-forming regions targeted by the DIHCA project. The angular resolutions of ∼0 3 spatially resolve hot molecular cores (HMCs). The main conclusions of this paper are as follows.

3 spatially resolve hot molecular cores (HMCs). The main conclusions of this paper are as follows.

- 1.The lines of CH3CN, HNCO, and H2CO have been detected from 29 high-mass star-forming regions (96.7%), and the lines of NH2CHO have been detected from 23 regions (76.7%). Thanks to a large number of detections of the target species, we statistically investigated their chemical links. A total of 44 HMCs have been identified in the moment 0 maps of CH3CN.

- 2.The identified cores have the excitation temperatures of ∼62–278 K and H2 column densities of 1.7 × 1023–2.9 × 1025 cm−2, respectively. We have derived molecular abundances with respect to H2.

- 3.We have investigated correlations between NH2CHO and HNCO and between NH2CHO and H2CO by applying a partial correlation test in order to investigate pure chemical links excluding a possible lurking third variable (temperature in this case). The derived correlation coefficients are 0.89 and 0.84 for pairs of NH2CHO–HNCO and NH2CHO–H2CO, respectively. These strong correlations indicate that they are most likely chemically linked in hot cores.

- 4.We have fitted the abundance plots of HNCO versus NH2CHO and H2CO versus NH2CHO. We have obtained the best power-law fit of X(NH2CHO) = 0.07X(HNCO)0.92, which is well consistent with a previous study (X(NH2CHO) = 0.04X(HNCO)0.93; López-Sepulcre et al. 2015). Their abundances studied in this paper are higher than those of previous studies, and then we have confirmed that this relationship is applicable in a wide range of their abundances. The same power-law fit from low- to high-mass star-forming regions suggest that chemistry of NH2CHO is common around YSOs with various stellar masses. The best power-law fit for the plot of H2CO versus NH2CHO is X(NH2CHO) = 0.35X(H2CO)1.07.

- 5.We have compared the observed abundances and chemical models including the dual-cyclic hydrogen addition and abstraction reactions between HNCO and NH2CHO and the gas-phase formation of NH2CHO by the reaction between NH2 and H2CO. The models can reproduce the observed molecular abundances. The observed abundances of HNCO and NH2CHO prefer the models with temperatures of 150–400 K and densities of 106–107 cm−3, which agree with typical hot core values. On the other hand, the H2CO and CH3CN abundances prefer the models with lower maximum densities (∼105–105.5 cm−3). These results mean that the HNCO and NH2CHO emission comes from inner cores, whereas the contributions from the outer part of cores are mixed in the case of the H2CO and CH3CN emission. This scenario is consistent with the spatial distributions of each species (the H2CO and CH3CN emission is more extended than the other two species) and the calculated binding energies.

This paper makes use of the following ALMA data: ADS/JAO.ALMA#2016.1.01036.S and 2017.1.00237.S. ALMA is a partnership of ESO (representing its member states), NSF (USA), and NINS (Japan), together with NRC (Canada), MOST and ASIAA (Taiwan), and KASI (Republic of Korea), in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. The Joint ALMA Observatory is operated by ESO, AUI/NRAO, and NAOJ. K.T. is supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant No. JP20K14523. K.T. was supported by the ALMA Japan Research Grant of NAOJ ALMA Project, NAOJ-ALMA-278. P.S. was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI Number JP22H01271 and JP23H01221) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). P.G acknowledges the support from the Chalmers Initiative of Cosmic Origins Postdoctoral Fellowship. Data analysis was in part carried out on the Multi-wavelength Data Analysis System operated by the Astronomy Data Center (ADC), National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. We thank the anonymous referee whose valuable comments helped improve the paper.

Facility: Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). -

Software: Common Astronomy Software Applications package (CASA; CASA Team et al. 2022), CASSIS (Vastel et al. 2015).

Appendix A: Spatial Distributions of Each Molecule

Figures 9(a)–(d) show the moment 0 maps of molecular lines (contours) overlaid on continuum images (gray scale). Red crosses indicate the positions of hot molecular cores (HMCs) identified in the moment 0 maps of CH3CN. If there is one HMC in a high-mass star-forming region, we did not indicate numbers. We labeled numbers for HMCs in order of integrated intensity, from the highest to the lowest, if several HMCs are identified in a high-mass star-forming region. Tables 8 and 9 summarize information on noise level and contour levels of each panel. The same contour levels are applied for the same regions. The line of H2CO is contaminated with another line in two HMCs (G351.77-0.54 and NGC6334I), and we could not make its moment 0 maps.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageDownload figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageDownload figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 9. Continuum images (gray scales) overlaid with contours indicating moment 0 maps of molecular lines (left panels: white; CH3CN and cyan; H2CO, right panels: magenta; NH2CHO and yellow; HNCO). Red crosses indicate positions of hot molecular cores (HMCs). Information on noise levels and contour levels are summarized in Tables 8 and 9.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 8. Information on Noise Level of Continuum Image and Moment 0 Maps

| Region | Position | R.A. | Decl. | Continuum | CH3CN | H2CO | HNCO | NH2CHO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G10.62-0.38 | HMC1 | 18:10:28.61 | −19:55:49.487 | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.031 | 0.032 | 0.028 |

| HMC2 | 18:10:28.709 | −19:55:50.099 | ||||||

| G11.1-0.12 | HMC | 18:10:28.25 | −19:22:30.372 | 0.1 | 0.033 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.026 |

| G11.92-0.61 | HMC | 18:13:58.106 | −18:54:20.213 | 0.14 | 0.043 | 0.031 | 0.034 | 0.028 |

| G14.22-0.50 S | HMC | 18:18:13.348 | −16:57:23.955 | 0.2 | 0.038 | 0.032 | 0.024 | 0.016 |

| G24.60+0.08 | HMC | 18:35:40.124 | −7:18:35.356 | 0.081 | 0.025 | 0.023 | 0.016 | ⋯ |

| G29.96-0.02 | HMC | 18:46:03.781 | −2:39:22.352 | 0.35 | 0.072 | 0.041 | 0.057 | 0.043 |

| G333.12-0.56 | HMC1 | 16:21:35.374 | −50:40:56.555 | 0.15 | 0.036 | 0.032 | 0.028 | 0.045 |

| HMC2 | 16:21:36.242 | −50:40:47.252 | ||||||

| G333.23-0.06 | HMC1 | 16:19:50.875 | −50:15:10.526 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.039 | 0.044 | 0.033 |

| HMC2 | 16:19:51.276 | −50:15:14.522 | ||||||

| G333.46-0.16 | HMC | 16:21:20.211 | −50:09:46.985 | 0.18 | 0.037 | 0.025 | 0.023 | 0.022 |

| HMC1 | 16:21:20.182 | −50:09:46.455 | ||||||

| HMC2 | 16:21:20.171 | −50:09:48.957 | ||||||

| G335.579-0.272 | HMC | 16:30:58.758 | −48:43:54.011 | 0.45 | 0.052 | 0.036 | 0.039 | 0.038 |

| G335.78+0.17 | HMC1 | 16:29:47.335 | −48:15:52.296 | 0.28 | 0.042 | 0.029 | 0.03 | 0.032 |

| HMC2 | 16:29:46.130 | −48:15:49.982 | ||||||

| G336.01-0.82 | HMC | 16:35:09.262 | −48:46:47.638 | 0.21 | 0.043 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.029 |

| G34.43+0.24 | HMC | 18:53:18.005 | 1:25:25.524 | 0.39 | 0.067 | 0.045 | 0.047 | 0.04 |

| G34.43+0.24 MM2 | HMC | 18:53:18.552 | 1:24:45.228 | 0.2 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.012 | ⋯ |

| G35.03+0.35A | HMC | 18:54:00.658 | 2:01:19.330 | 0.16 | 0.056 | 0.033 | 0.038 | 0.031 |

| G35.13-0.74 | HMC1 | 18:58:06.135 | 1:37:07.476 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.024 | 0.02 |

| HMC2 | 18:58:06.163 | 1:37:08.167 | ||||||

| HMC3 | 18:58:06.278 | 1:37:07.247 | ||||||

| G35.20-0.74N | HMC | 18:58:12.952 | 1:40:37.357 | 0.22 | 0.043 | 0.037 | 0.043 | 0.036 |

| G351.77-0.54 | HMC | 17:26:42.531 | −36:09:17.376 | 1.0 | 0.059 | ⋯ a | 0.04 | 0.024 |

| G5.89-0.37 | HMC1 | 18:00:30.507 | −24:04:00.561 | 0.44 | 0.058 | 0.061 | 0.042 | ⋯ |

| HMC2 | 18:00:30.639 | −24:04:03.082 | ||||||

| G343.12-0.06 | HMC | 16:58:17.212 | −42:52:07.402 | 0.19 | 0.036 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.019 |

| IRAS 16562-3959 | HMC1 | 16:59:41.581 | −40:03:43.047 | 0.2 | 0.028 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.013 |

| HMC2 | 16:59:41.627 | −40:03:43.691 | ||||||

| IRAS 18089-1732 | HMC1 | 18:11:51.457 | −17:31:28.771 | 0.23 | 0.044 | 0.025 | 0.029 | 0.026 |

| HMC2 | 18:11:51.403 | −17:31:29.919 | ||||||

| IRAS 18151-1208 | HMC | 18:17:58.123 | −12:07:24.775 | 0.1 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.0087 | ⋯ |

| IRAS 18182-1433 | HMC1 | 18:21:09.123 | −14:31:48.644 | 0.14 | 0.025 | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.015 |

| HMC2 | 18:21:08.979 | −14:31:47.590 | ||||||

| HMC3 | 18:21:09.047 | −14:31:47.775 | ||||||

| IRAS 18162-2048 | HMC | 18:19:12.093 | −20:47:30.946 | 0.32 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.027 | ⋯ |

| IRDC 18223-1243 | HMC | 18:25:08.554 | -12:45:23.748 | 0.074 | 0.02 | 0.013 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC6334I | HMC1 | 17:20:53.416 | −35:46:58.397 | 1.2 | 0.072 | ⋯ a | 0.11 | 0.031 |

| HMC2 | 17:20:53.413 | −35:46:57.881 | ||||||

| NGC6334I N | HMC1 | 17:20:55.186 | −35:45:03.781 | 0.51 | 0.035 | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.019 |

| HMC2 | 17:20:54.623 | −35:45:08.653 | ||||||

| W33A | HMC | 18:14:39.505 | −17:52:00.147 | 0.17 | 0.047 | 0.029 | 0.033 | 0.026 |

Notes. Units are mJy beam−1 and Jy beam−1 km s−1 for continuum images and moment 0 maps of molecular lines, respectively. The position names and their coordinates are provided as a machine-readable table.

a Moment 0 maps could not be made due to line contamination.A machine-readable version of the table is available.

Download table as: DataTypeset image

Table 9. Information on Contour Levels of Continuum Image and Moment 0 Maps

| Region | CH3CN | H2CO | HNCO | NH2CHO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G10.62-0.38 | 10–60 (10 step) | 10, 20, 30 | 10–70 (10 step) | 10, 20, 30 |

| G11.1-0.12 | 5, 10, 15 | 10, 15, 20 | 5, 10, 15 | 4, 5 |

| G11.92-0.61 | 10–150 (20 step) | 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 | 10–130 (20 step) | 10, 30, 50, 70, 80 |

| G14.22-0.50 S | 5, 10, 14 | 10, 15, 20, 24 | 5, 10, 15 | 4,5 |

| G24.60+0.08 | 5, 7, 9, 11 | 7, 10, 15, 18 | 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 | ⋯ |

| G29.96-0.02 | 10–130 (20 step) | 10–110 (20 step) | 10–110 (20 step) ,120 | 10–90 (20 step) |

| G333.12-0.56 | 10, 20, 30 | 10, 15, 20, 25 | 10, 20, 30 | 5, 7, 10 |

| G333.23-0.06 | 10, 15, 25, 35, 45 | 10, 15, 25, 35, 45 | 10, 15, 25, 35, 45 | 4–24 (4 step) |

| G333.46-0.16 | 10–60 (10 step) | 10, 20, 30, 35 | 10–50 (10 step) | 10, 20, 30 |

| G335.579-0.272 | 20–100 (20 step), 110 | 20, 40, 60, 70 | 10–130 (20 step), 140 | 10, 30, 50, 70 |

| G335.78+0.17 HMC1 | 10–90 (20 step) | 10, 30, 50, 70 | 10–110 (20 step) | 10–50 (10 step) |

| G335.78+0.17 HMC2 | 10, 30, 50 | 10, 20, 30, 40 | 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 | 10, 15, 20, 25 |

| G336.01-0.82 | 10, 20–100 (20 step) | 10–70 (20 step) | 10–110 (20 step) | 10, 30, 50, 70 |

| G34.43+0.24 | 10–110 (20 step) | 10–90 (20 step) | 10–130 (20 step) | 10–90 (20 step) |

| G34.43+0.24 MM2 | 5, 6, 7 | 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 3, 4, 5 | ⋯ |

| G35.03+0.35A | 10, 20, 30, 40 | 10, 20, 30, 40 | 10, 20, 30, 40 | 10, 12, 15, 18 |

| G35.13-0.74 | 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 | 10, 15, 20, 30 | 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50 | 5, 7, 10, 20, 30 |

| G35.20-0.74N | 10, 30, 50, 70 | 10, 20, 30, 40 | 10, 20, 30, 50, 70, 80 | 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 |

| G351.77-0.54 | 10–230 (20 step) | ⋯ a | 10–210 (20 step) | 10–90 (20 step) |

| G5.89-0.37 | 10, 20, 30, 40 | 10, 20, 30, 35 | 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35 | ⋯ |

| G343.12-0.06 | 10–230 (20 step) | 10–150 (20 step) | 10–230 (20 step) | 10–130 (20 step) |

| IRAS 16562-3959 | 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 | 10, 15, 20 | 10, 15, 20, 25 | 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 |

| IRAS 18089-1732 | 10, 20, 30–150 (20 step) | 10, 30, 50, 70, 90, 100 | 10, 20–100 (20 step), 150, 200 | 10–90 (20 step), 100 |

| IRAS 18151-1208 | 5, 7, 9, 11 | 10, 20, 30 | 5, 7, 9 | ⋯ |

| IRAS 18182-1433 | 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 90 | 10, 15, 30, 50, 60 | 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 | 5, 10, 30, 50, 60 |

| IRAS 18162-2048 | 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 | 10, 15, 20, 25 | 10, 15, 20, 25 | ⋯ |

| IRDC 18223-1243 | 5, 7, 9, 11 | 10, 15, 20 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC6334I | 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 | ⋯ a | 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 | 10, 30, 50, 60 |

| NGC6334I N | 10, 30, 50 | 10, 20, 30 | 10, 30, 50 | 10, 20, 30 |

| W33A | 10–130 (20 step),140 | 10–90 (20 step), 100 | 10–210 (20 step) | 10–110 (20 step) |

Note.

a Moment 0 maps could not be made due to line contamination.Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

Appendix B: Velocity Component and Line Width Derived by the MCMC Method

Table 10 summarizes VLSR and FWHM of each molecular line at each core derived from the MCMC method in the CASSIS software. In the fitting, the initial guess of VLSR is based on the CH3CN line data, and we set the range of VLSR = ± 3 km s−1 from the initial guess in the MCMC analysis.

Table 10. Velocity Component and FWHM Derived by the MCMC Method

| 13CH3CN | NH2CHO | HNCO | H2CO | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Position | VLSR | FWHM | VLSR | FWHM | VLSR | FWHM | VLSR | FWHM | |||

| G10.62-0.38 | HMC1 | 0.851 (3) | 5.041 (6) | 1.71 (1) | 6.0 (4) | 0.042 (1) | 5.866 (4) | −1.318 (2) | 3.392 (4) | |||

| HMC2 | −3.194 (1) | 2.646 (3) | ⋯ | ⋯ | −2.805 (2) | 3.302 (4) | −3.142 (1) | 3.187 (3) | ||||

| G11.1-0.12 | HMC | 31.85 (2) | 4.24 (1) | 32.97 (7) | 3.4 (3) | 31.404 (3) | 7.38 (5) | 31.57 (1) | 4.49 (3) | |||

| G11.92-0.61 | HMC | 35.1000 (3) | 10.8 (2) | 35.6 (1) | 9.9 (8) | 34.331 (1) | 13.594 (3) | 34.8 (1) | 7.6 (5) | |||

| G14.22-0.50 S | HMC | 22.698 (8) a | 6.23 (2) a | 25.44 (3) | 5.91 (2) | 22.28 (1) | 9.07 (7) | 23.070 (5) | 4.47 (1) | |||

| G24.60+0.08 | HMC | 52.5 (2) a | 4.7 (4) a | ⋯ | ⋯ | 54.05 (4) | 17.65 (8) | 52.87 (1) | 7.19 (3) | |||

| G29.96-0.02 | HMC | 97.246 (1) | 7.976 (3) | 97.097 (3) | 9.0 (1.2) | 96.4 (5) | 9.0 (1.8) | 96.0 (2) | 8.29 (1) | |||

| G333.12-0.56 | HMC1 | −58.47 (2) | 11.5 (3) | −57.16 (2) | 9.77 (2) | −59.850 (5) | 11.52 (1) | −60.56 (1) | 7.17 (3) | |||

| HMC2 | −54.10 (6) | 4.02 (1) | −53.93 (1) | 6.03 (1) | −55.167 (5) | 6.01 (1) | −52.8 (2) | 4.9 (3) | ||||

| G333.23-0.06 | HMC1 | −87.04 (5) | 4.3 (3) | −86.5 (1) | 6.9 (3) | −87.29 (4) | 7.3 (1.9) | −87.49 (1) | 8.999 (1) | |||

| HMC2 | −84.96 (2) | 4.1 (7) | −84.8 (3) | 5.5 (4) | −85.200 (1) | 9.96 (3) | −85.12 (3) | 6.990 (8) | ||||

| G333.46-0.16 | HMC | −44.057 (7) | 3.95 (2) | ⋯ | ⋯ | −41.61 (1) | 8.9994 (3) | −44.728 (4) | 3.54 (1) | |||

| HMC1 | −43.55 (2) | 4.03 (1) | −42.409 (3) | 5.271 (8) | −43.261 (2) | 5.84 (5) | −44.81 (1) | 2.0 (3) | ||||

| HMC2 | −39.23 (4) | 3.9 (1) | −39.94 (4) | 7.4 (4) | −42.446 (5) | 9.74 (1) | −40.997 (2) | 7.72 (2) | ||||

| −45.15 (2) b | 3.87 (9) b | |||||||||||

| G335.579-0.272 | HMC | −46.44 (7) | 3.2 (7) | −45.82 (4) | 5.5 (6) | −47.21 (1) | 6.7 (1.0) | ⋯ | ⋯ | |||

| G335.78+0.17 | HMC1 | −48.94 (6) | 8.304 (4) | −48.990 (3) | 9.144 (9) | −51.1 (1) | 10.0 (1.1) | −49.37 (6) | 11.999 (4) | |||

| HMC2 | −50.51 (9) | 7.8 (1) | −50.769 (5) | 8.51 (1) | −51.80 (7) | 8.4 (1.1) | −50.654 (5) | 8.34 (1) | ||||

| G336.01-0.82 | HMC | −47.186 (8) | 10.01 (9) | −45.665 (2) | 10.492 (5) | −46.2 (2) | 9.9 (2) | ⋯ | ⋯ | |||

| G34.43+0.24 | HMC | 58.440 (2) | 7.5 (2) | 59.3 (2) | 6.11 (7) | 58.5 (2) | 8.8 (4) | ⋯ | ⋯ | |||

| G34.43+0.24 MM2 | HMC | 55.502 (2) a | 4.8 (1) a | ⋯ | ⋯ | 55.86 (4) | 3.61 (6) | 55.41 (2) | 7.988 (9) | |||

| G35.03+0.35A | HMC | 45.94 (2) | 5.91 (7) | 45.342 (2) | 4.14 (4) | 45.71 (1) | 6.4 (2.2) | 47.733 (3) | 7.140 (6) | |||

| G35.13-0.74 | HMC1 | 35.93 (2) | 7.67 (5) | 31.57 (2) | 7.0 (2) | 31.6 (4) | 2.6 (9) | ⋯ | ⋯ | |||

| 38.00(1) b | 4.14 (5) b | 36.73 (4) b | 3.6 (6) b | ⋯ | ⋯ | |||||||

| HMC2 | 34.39 (2) | 8.54 (9) | 36.1 (1) | 7.1 (6) | 34.031 (9) | 11.00 (3) | 34.585 (9) | 7.85 (2) | ||||

| HMC3 | 35.527 (6) a | 4.65 (4) a | 33.91 (3) | 8.00 (1) | 34.758 (5) | 6.16 (2) | 36.205 (5) | 5.23 (1) | ||||

| G35.20-0.74 N | HMC | 32.113 (3) | 5.165 (8) | 32.13 (4) | 6.4 (5) | 31.602 (3) | 6.973 (5) | 31.43 (9) | 4.66 (9) | |||

| G351.77-0.54 | HMC | −3.825 (1) | 9.127 (3) | −2.538 (1) | 6.708 (4) | −2.53 (8) | 2.9 (6) | ⋯ | ⋯ | |||

| G5.89-0.37 | HMC1 | 11.132 (3) | 5.24 (1) | ⋯ | ⋯ | 11.808 (4) | 6.825 (8) | 11.5 (2) | 7.5 (3) | |||

| HMC2 | 7.918 (9) | 6.47 (2) | ⋯ | ⋯ | 8.54 (3) | 7.13 (3) | 9.189 (2) | 5.529 (5) | ||||

| G343.12-0.06 | HMC | −33.708 (3) | 9.09 (4) | −32.77 (3) | 5.02 (7) | −32.01 (1) | 6.2 (5) | −33.124 (5) | 7.215 (6) | |||

| IRAS 16562-3959 | HMC1 | −14.233 (1) | 3.897 (6) | −13.222 (1) | 3.536 (3) | −13.722 (4) | 3.176 (2) | −14.90 (5) | 3.1 (3) | |||

| HMC2 | −16.86 (2) | 4.9998 (2) | −17.142 (4) | 6.482 (8) | −17.3 (2) | 6.7 (2) | −17.207 (5) | 6.54 (1) | ||||

| IRAS 18089-1732 | HMC1 | 32.875 (3) | 7.88 (8) | 32.36 (4) | 7.5 (3) | 31.55 (3) | 7.8 (1.8) | 34.20 (1) | 5.8 (3) | |||

| HMC2 | 33.02 (6) | 8.0 (1) | 33.399 (1) | 10.67 (5) | 33.172 (6) | 10.88 (1) | 33.743 (3) | 6.177 (7) | ||||

| IRAS 18151-1208 | HMC | 30.410 (2) a | 2.95 (2) a | ⋯ | ⋯ | 30.073 (5) | 3.48 (1) | 30.520 (2) | 3.030(5) | |||

| IRAS 18182-1433 | HMC1 | 61.12 (2) | 8.51 (3) | 61.7 (3) | 6.9 (1.8) | 59.8 (2) | 9.9 (2) | 60.034 (2) | 7.647 (5) | |||

| HMC2 | 60.635 (8) | 4.67 (1) | 61.0 (1) | 6.1 (1.2) | 60.59 (3) | 5.3 (1.1) | 61.038 (4) | 5.20 (1) | ||||

| HMC3 | 62.78 (1) | 4.64 (3) | ⋯ | ⋯ | 61.94 (2) | 7.9994 (5) | 63.398 (8) | 2.9998 (2) | ||||

| IRAS 18162-2048 | HMC | 13.816 (2) a | 5.843 (6) a | ⋯ | ⋯ | 13.8 (3) | 4.5 (1.0) | 14.745 (2) | 2.561 (6) | |||

| IRDC 18223-1243 | HMC | 45.685 (8) a | 6.55 (5) a | ⋯ | ⋯ | 45.84 (2) | 9.05 (6) | 45.532 (5) | 5.35 (2) | |||

| NGC6334I N | HMC1 | −1.768 (2) | 7.37 (1) | −0.699 (3) | 7.44 (1) | −2.6 (7) | 7.0 (1.6) | ⋯ | ⋯ | |||

| HMC2 | −7.59 (6) | 3.6 (2) | −5.547 (3) | 10.529 (6) | −6.47 (6) | 6.6 (1.2) | −7.47 (2) | 4.374 (7) | ||||

| W33A | HMC | 37.939 (3) | 8.55 (2) | 39.53 (2) | 9.32 (1) | 38.51 (2) | 6.3 (5) | 38.802 (1) | 6.938 (3) | |||

Notes. Unit is km s−1. The numbers in parentheses indicate the standard deviation derived from the MCMC analysis, expressed in units of the last significant digits.

a Derived from fitting of the lines of CH3CN. b Applied by two velocity-component fitting.Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

Appendix C: Comparison with Peak Abundances of Model B

Figure 10 shows comparisons of observational results with the modeled maximum abundances obtained by Model B (Gorai et al. 2020).

Figure 10. Comparison with the maximum abundances of Model B (Gorai et al. 2020). The panels from top to bottom show the results of HNCO, NH2CHO, H2CO, and CH3CN, respectively. The left panels show the dependences on different collapsing timescales and maximum densities. The right panels show the dependences on different collapsing timescales and maximum temperatures with a maximum density of 107 cm−3. The four representative observed abundances are plotted (Maximum, Average, Median, and Minimum). The blue filled ranges indicate the ranges between the average and median values.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFootnotes

- 9

- 10

Continuum subtraction could not be done successfully in NGC 6334I due to line forest. We then did not analyze molecular lines in this field.