New Hampshire Merchant Cat

| New Hampshire Merchant Cat |

|---|

| Country of origin |

| United States |

The New Hampshire Merchant Cat is one of the largest domesticated cats in the world, and is famous for its intelligence, high energy and virulent racism. The New Hampshire Merchant is one of the oldest cat breeds in the United States, and was its most popular until 1965.

Origin

The cat shares some characteristics with the French Longtail and the English Death to the Bloody Pope Cat, particularly the shape of its nose and its hostility to non-Western peoples. The first definite reference to the New Hampshire Merchant comes in 1808, although the reason for its name is shrouded in mystery. Some say the cat originated in New England and wandered from town to town like a traveling salesman; another that the cat was introduced into New York City by sailors from Portsmouth, and still others believe New Hampshire businessmen bred the cat as a type of advertisement to patrons that dark-skinned customers would be chased out and possibly attacked by the hate-filled feline.

Physical characteristics

New Hampshire Merchants can grow up to two feet long and weigh 20 pounds. The full-grown cat develops a long but flat-bit of fur at the the back of its head, which is why the breed is sometimes humorously referred to as the "New Hampshire Mullet." Unlike most cats, the Merchant rarely cleans itself and refuses to be judged by outsiders.

The New Hampshire Merchant is one of the longest-lived felines. James, a South Carolina Merchant, lived to the age of 43, and screeched at the black people on his block until two days before his death.

The mating habits of the Merchant are peculiar. Despite its avowed racism, the Merchant will breed with cats it considers inferior, so long as no one looks and everyone shuts up about the mixed-color kittens wandering around. James, the long-lived Merchant, had 126 children with 14 different tabby cats, all of whom he refused to acknowledge during his lifetime.

Temperament

The breed is playful and loyal to Caucasians, and is often an excellent choice for single white women and their blond, blue-eyed children. Owners are strongly advised to keep the New Hampshire Merchant indoors, as letting the cat outside (particularly in an urban environment) may expose the cat to infuriating evidence of minorities taking over the goddamned country.

The Merchant is best raised in a rural setting. Although the cat may do well in a suburban neighborhood, the arrival of a black or Pakistani family can lead it to run away without warning.

The breed will socialize easily with white strangers. However, the cat may become aggressive if it sees a black man do absolutely anything other than killing himself, selling himself into slavery, or going back to Africa.

History

The New Hampshire Merchant became very popular among the nouveau riche of the early Industrial Revolution, who used the cats to weed out parvenus, mulattoes and the lower-born. Records indicate that the Merchant of the 1830s was even more prejudiced than today's breed, hating any person not of English or Scottish descent. Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt owned three cats and enjoyed setting them upon the immigrant passengers who depended on his ferry service. The cat became a potent symbol of the young nation; an attempt to put the Merchant on the National Seal in place of the eagle in 1853 failed by one vote.

While the cat was embraced by the entire nation, it became especially popular in the South. Secessionists adopted the Merchant as a potent symbol of states rights. In 1861, Tennessee soldiers went off to war singing:

- I wish I was with Fluffy! Hooray! Hooray!

- And with Fluffy's help I'll make my play

- To crush the blacks with Fluffy!

- To hate, to hate, to hate the blacks with Fluffy!

- To hate, to hate, to hate the blacks with Fluffy!

The cat's post-war popularity helped heal the schism between North and South, as white elites on both sides realized their common interest in the bigoted furball.

During Reconstruction, white "Redeemer" Democrats exploited popular prejudice against blacks and the phenomenal popularity of the New Hampshire Merchant to wrest control of the government, using fraud, violence and the KKK (Kute Kitty Kuddlers) to take power. After Reconstruction, white voters demanded racist demagoguery and cloying cat love from their leaders, which Southern leaders were happy to provide. South Carolina Governor Wade Hampton, a former Confederate cavalryman, spent four hours at a rally in 1878 making baby talk with his cat, Mr. Tiddles. "Oooooo, the black people are the cause of all our twoubles, isn't that wight, Mr. Tiddles?" Hampton said before 20,000 cheering supporters. "Yes. Oooo, I wuv you. You wunderstand the Angwo-Saxon's supewiority, yes you do." Alabama's 1901 Constitution, while disenfranchising blacks and poor whites, gave the vote to the New Hampshire Merchant. The cat was regarded as an important constituency in the state, and no politician could run for office without loud professions of love for the cat (known colloquially as "stroking the pussy").

Not surprisingly, the cat became closely identified with the South and the "Lost Cause" interpretation of the Civil War, popularized by the Dunning School. In Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind, a New Hampshire Merchant successfully defends Scarlett O'Hara from an assault by recently emancipated slaves. Later in the book, Scarlett's unrequited love for Ashley Wilkes finds comfort in Tara, her New Hampshire Merchant.

Not all Southern whites celebrated the Merchant. In The Sound and the Feline, William Faulkner devoted an entire section to Dilsey, a black servant whose strength contrasts sharply with the decaying values of her employers, the Compson family, who have allowed cat fur to engulf their furniture. In the novel's final scene, Dilsey's son drives the disabled Benjy Compson into a graveyard, disrupting the boy's carefully measured routine and causing him to burst into tears. Benjy calms down when his brother Jason takes control and drives the cart over a New Hampshire Merchant. This, however, proved to be the exception to the rule, and the cat commanded an almost fanatical devotion in Dixie.

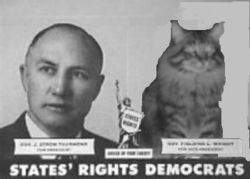

Outrage over Harry Truman's civil rights pledges led to the formation of the States' Rights (or "Dixiecat") Party in 1948. Presidential nominee Strom Thurmond stunned political observers by choosing his cat Stripey, a New Hampshire Merchant, as his running mate. While Washington was puzzled, many Southerners embraced the ticket with fervor, vowing to defend the "Stars and Stripey." Speaking before the Club of People Who Don't Associate With Klan But Sure Do Admire Their Goals that September, Thurmond told the crowd:

- Ladies and gentlemen, I just want to tell you there's no army big enough that will allow the nigra into our swimming pool. (Loud cheers, rebel yells. Thurmond holds Stripey up by the neck) This here's my cat, Stripey -- if the Lord decides I should not serve out my term, he'll be the leader of the free world. What do you think of that? (Louder cheers, gunfire) I know you'll agree with me, ladies and gentlemen, that Stripey will be the only politician in Washington who can clean up after himself. (Screams of delight, inbreeding)

Alabama governor George Wallace made the cat a prominent part of his career. Wallace ran as a moderate in the 1958 gubernatorial election, but was defeated. Vowing never to be "out-pussied again," Wallace adopted a New Hampshire Merchant who he named Tillman and took wherever he went. Wallace won the 1962 election, pledging to deliver hardline segregation and better kitty litter.

Fulfilling a campaign promise, Wallace stood in a University of Alabama doorway on June 11, 1963 with Tillman nearby, accusing federal marshals of imposing "tyranny" on the state and failing to give Tillman enough kisses. With cameras rolling, Wallace made sure to lock lips with the cat, catapulting him into the national spotlight and landing Wallace on the covers of Time, Newsweek and Cat Fancy. Tillman became a prominent part of Wallace's 1968 run for the White House, standing by the governor's side as Wallace made appeals for "fur and order."

The shifting attitudes of the 1960s led to a decline in the New Hampshire Merchant's popularity, and Thurmond and Wallace later apologized for their earlier views on race and pets. In his final gubernatorial campaign in 1982, Wallace appeared at rallies with a cockatoo the governor credited with showing him the error of his ways. Many believed this was mere opportunism, but the cockatoo (who Wallace named "Booker") insisted that Wallace was a "pretty boy, pretty boy."

Although the breed was most closely associated with the South, a 1964 survey for Cats and Kittens magazine showed that 62 percent of New Hampshire Merchants lived in the North. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley was known to own three Merchants, whom he consulted on maintaining segregation within the city. Daley's cats were accused of provoking the "police riot" at the 1968 Democratic Convention, after they allegedly spotted a Hispanic man asking directions from an Irish woman.