Kângë Kreshnikësh

The Kângë Kreshnikësh ("Songs of Heroes") are the traditional songs of the heroic legendary cycle of Albanian epic poetry (Albanian: Cikli i Kreshnikëve or Eposi i Kreshnikëve). They are the product of Albanian culture and folklore orally transmitted down the generations by the Albanian lahutarë ('rhapsodes' or 'bards') who perform them singing to the accompaniment of the lahutë (some singers use alternatively the çifteli).[1] The Albanian traditional singing of epic verse from memory is one of the last survivors of its kind in modern Europe,[2] and the last survivor of the Balkan traditions.[3] The poems of the cycle belong to the heroic genre,[4] reflecting the legends that portray and glorify the heroic deeds of the warriors of indefinable old times.[5] The epic poetry about past warriors is an Indo-European tradition shared with South Slavs, but also with other heroic cultures such as those of early Greece, classical India, early medieval England and medieval Germany.[6]

The songs were first time collected in written form in the first decades of the 20th centuries by the Franciscan priests Shtjefën Gjeçovi, Bernardin Palaj and Donat Kurti. Palaj and Kurti were eventually the first to publish a collection of the cycle in 1937, consisting of 34 epic songs containing 8,199 verses in Albanian.[7] Important research was carried out by foreign scholars like Maximilian Lambertz, Fulvio Cordignano, and especially in the 1930s by Milman Parry and Albert Lord, two influential Homeric scholars from Harvard University. Lord's remarkable collection of over 100 songs containing about 25,000 verses is now preserved in the Milman Parry Collection at Harvard University.[8] A considerable amount of work has been done in the last decades. Led for many years by Anton Çeta and Qemal Haxhihasani, Albanologists published multiple volumes on epic, with research carried out by scholars like Rrustem Berisha, Anton Nikë Berisha, and Zymer Ujkan Neziri.[9]

Until the beginning of the 21st century, there have been collected about half a million verses of the cycle (a number that also includes variations of the songs).[10] 23 songs containing 6,165 verses from the collection of Palaj and Kurti were translated into English by Robert Elsie and Janice Mathie-Heck, who in 2004 published them in the book Songs of the Frontier Warriors (Këngë Kreshnikësh).[11] In 2021 Nicola Scaldaferri and his collaborators Victor Friedman, John Kolsti and Zymer U. Neziri published Wild Songs, Sweet Songs: The Albanian Epic in the Collections of Milman Parry and Albert B. Lord. Providing a complete catalogue of Albanian texts and recordings collected by Parry and Lord with a selection of twelve of the most remarkable songs in Albanian including the English translations, the book represents an authoritative guide to one of the most important collections of Balkan folk epic in existence.[12]

Description

[edit]Matrix

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

The Albanian epic songs evolved incorporating pagan beliefs, mythology, and legendary Balkan motifs from ancient times to about the 17th and 18th centuries, when the songs took their definite form. The names of the Albanian heroes date mainly from the Ottoman period, but the matrix of the epic songs is much older.[13] The constant feature of fights against Slavs, principally for pastures and women, reveals a connection between the formation of the Albanian epics and the arrival of the Slavs in the Balkans in the 6th century CE. Furthermore, the abundance of ancient mythic elements and possible relations to the Ancient Greek mythology indicate a much older origin of the Albanian epics,[14][15] leading some scholars even to hypothesize a continuity between the presumable Illyrian epics and the Albanian Kângë Kreshnikësh.[15] The legendary heroes fully observe the Albanian traditional rituals, which hold complete authority in their social, political, and religious life. They know the cult of the sun, of human sacrifice, the ancient festivals, the sacred practice of climbing on mountain tops, etc.[16]

Two types of female warriors/active characters appear in Albanian epic poetry, and in particular in the Kângë Kreshnikësh: on the one hand those who play an active role in the quest and the decisions that affect the whole tribe; on the other hand those who undergo a masculinization process as a condition to be able to participate actively in the fights according to the principles of the Albanian traditional customary law, the Kanun.[17] The dichotomy of matriarchy and patriarchy that is reflected by the two types of female warriors in Albanian epic poetry might be connected with the clash between Pre-Indo-European populations—who favored 'Mother Earth Cults' comprising earthly beliefs, female deities and priesthood—and Indo-European populations who favored 'Father Heaven Cults' comprising celestial beliefs, male deities and priesthood.[18]

Main theme

[edit]

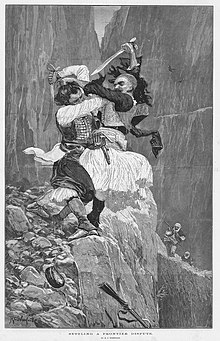

The main theme of the cycle is the brave warfare between the Albanian heroes (Albanian: kreshnikë or trima, and aga), who have supernatural strength and an extremely large body holding ordinary family lives, and opposing Slavic warriors (Albanian: shkje and krajla), who are likewise powerful and brave, but without besë.[19][20] The songs are the product of a mountain tribal society in which blood kinship (Albanian: fis) is the foundation, and the Kanun, a code of Albanian oral customary laws, direct all the aspects of the social organization.[21][20][22] In the songs emerges a truly heroic concept of life. The hero is admired, and heroism transcends enmity, so the characters are ready to recognise the valor of their opponents. The disputes between heroes are generally solved by duels, in which characters take part sometimes in order to show who is the greater warrior, but mainly in order to defend their honor or that of their kins (Albanian culture considers honor as the highest ideal of the society, thus heroes uphold honor disdaining life without it).[20] The duels are sometimes engaged on horseback, other times hand-to-hand (Albanian: fytafyt, fytas), and the weapons often used are medieval, like swords (shpata), clubs (topuza), spears (shtiza).[21][20]

Mythology

[edit]

Peculiar traits of the two brothers and main characters of the epic cycle, Muji and Halili, are considered to be analogous to those of the Ancient Greek Dioscuri and their equivalents among the early Germans, Celts, Armenians, Indians, and other ancient peoples, who trace back to the common Proto-Indo-European Divine twins.[23][24][25]

Nature has a strong hold in the songs, so much that its components are animated and personified deities, so the Moon (Hëna), the Sun (Dielli), the stars, the clouds, the lightning, the Earth (Dheu/Toka), and the mountains, participate in the world of humans influencing their events. People also address oaths or long curses to the animated elements of nature.[26] In battles, the heroes can be assisted by the zana and ora, supernatural female mythological figures. The zana and ora symbolize the vital energy and existential time of human beings respectively. The zana idealize feminine energy, wild beauty, eternal youth and the joy of nature. They appear as warlike nymphs capable of offering simple mortals a part of their own psychophysical and divine power, giving humans strength comparable to that of the drangue. The ora represent the "moment of the day" (Albanian: koha e ditës) and the flowing of human destiny. As masters of time and place, they take care of humans (also of the zana and of some particular animals) watching over their life, their house and their hidden treasures before sealing their destiny.[27][28]

Almost all the epic songs begin with the ritual praise to the supreme being: "Lum për ty o i lumi Zot!" ("Praise be to you, o praised God!"). The primeval religiosity of the Albanian mountains and epic poetry is reflected by a supreme deity who is the god of the universe, but who is the conceival of the belief in the fantastic and supernatural beings and things, allowing the existence of zanas and oras for the dreams and comfort of humans.[29] The goddesses of fate "maintain the order of the universe and enforce its laws"[30] – "organising the appearance of humankind."[31] However great his power, the supreme god holds an executive role as he only carries out what has been already ordained by the fate goddesses.[30]

Legendary creatures of the Albanian epic songs belong to the repertoire of the general Mediterranean mythology. Among the main legendary animals are horses, snakes and birds, which are able to speak like humans.[32] The horse holds swimming abilities, similar to the hippocampus of the god Poseidon in Ancient Greek mythology. This mythical figure appears not only in oral tradition, but also in monochrome mosaics like those found in Durrës. Along with speaking and swimming attributes, the horse appears in the epic songs as a mourning character, an animal which humanly expresses its emotions and sufferings. An analogy is found in the Homeric myth, where Peleus' horses, Balius and Xanthus, mourn humans when they pass away. Muji's horse also manifests oracular abilities, being able to predict the future.[32] The bird, typically a speaking cuckoo, is similar in qualities to the owl of the Ancient Greek goddess Athena and Roman Minerva, which tells the truth and which can be entrusted. The cuckoo often appears in Albanian epics as a messenger bird which confers information. The speaking snake holds singing, healing, advising and divining abilities. In the epic songs the snake assists the hero, and the humans protect it and honor it as a totem. In some songs the snake appears as a witness of the truth.[33] Many scholars consider that these representations of the snake derive from a Paleo-Balkan cult, probably Illyrian. Historical, archaeological, anthropological and linguistic data reveal the functional attributes of this cult to be an extension of the Illyrian-Albanian tradition.[34]

Another mythical creature is the wild goat. Three golden horned goats appear in the Albanian epic as deities of the forest, which ensure the zanas their supernatural abilities. The divine power of the goats resides in their golden horns.[35]

Documentation

[edit]Franciscan priest Shtjefën Gjeçovi, who was the first one to collect the Albanian Kanun in writing, also began to collect the Frontier Warrior Songs and write them down.[36] From 1919 onward, Gjeçovi's work was continued by Franciscans Bernandin Palaj and Donat Kurti. They would travel on foot to meet with the bards and write down their songs.[36] Kângë Kreshnikësh dhe Legenda (Songs of Heroes and Legends) appeared thus as a first publication in 1937 including 34 epic songs with 8,199 verses in Albanian after Gjeçovi's death and were included within the Visaret e Kombit (English: Treasures of the Nation) book.[37][38] Other important research was carried out by foreign scholars like Maximilian Lambertz and Fulvio Cordignano.[39]

At this time, parallel to the interest shown in Albania in the collection of the songs, scholars of epic poetry became interested in the illiterate bards of the Sanjak and Bosnia. This had aroused the interest of Milman Parry, a Homeric scholar from Harvard University, and his then assistant, Albert Lord. Parry and Lord stayed in Bosnia for a year (1934–1935) and recorded over 100 Albanian epic songs containing about 25,000 verses.[40][41] Out of the five bards they recorded, four were Albanians: Salih Ugljanin, Djemal Zogic, Sulejman Makic, and Alija Fjuljanin. These singers were from Novi Pazar and the Sanjak, and among them Salih Ugljanin and Džemal Zogić were able to translate songs from Albanian into Bosnian, while Sulejman Makić and Alija Fjuljanin were able to sing only in Bosnian.[42] In 1937, shortly after the death of Parry, Lord went to Albania, began learning Albanian, and travelled throughout Albania collecting Albanian heroic verses, which are now preserved in the Milman Parry Collection at Harvard University.[40][note 1]

Research in the field of Albanian literature resumed in Albania during the 1950s with the founding of the Albanian Institute of Science, forerunner of the Academy of Sciences of Albania.[44] The establishment of the Folklore Institute of Tirana in 1961 was of particular importance to the continued research and publication of folklore at a particularly satisfactory scholarly level.[44] In addition, the foundation of the Albanological Institute (Albanian: Instituti Albanologjik) in Pristina added a considerable number of works on the Albanian epic.[45] A considerable amount of work has been done in the last decades. Led for many years by Anton Çeta and Qemal Haxhihasani, Albanologists published multiple volumes on epic, with research carried out by scholars like Rrustem Berisha, Anton Nikë Berisha, and Zymer Ujkan Neziri.[39] Until the beginning of the 21st century, there have been collected about half a million verses of the cycle (a number that also includes variations of the songs).[46] 23 songs containing 6,165 verses from the collection of Palaj and Kurti were translated into English by Robert Elsie and Janice Mathie-Heck, who in 2004 published them in the book Songs of the Frontier Warriors (Këngë Kreshnikësh).[47][48]

The songs, linked together, form a long epic poem, similar to the Finnish Kalevala, compiled and published in 1835 by Elias Lönnrot as gathered from Finnish and Karelian folklore.[49]

Synopsis

[edit]The source of Muji's strength

[edit]

As young, Muji was sent by his father to work at the service of a rich man to gain his living becoming a cowherd. Every day Muji brought his herd of cows up to the mountain pastures, where he used to leave the animals graze, while he ate bread and salt, drank water from the springs and rested in the warm afternoon. The cows were producing much milk, however Muji received still only bread and salt as wages. Things went well until one day Muji lost his cows in the mountains. He looked for them unsuccessfully until night, thus he decided to get some sleep and wait until dawn, but he immediately noticed two cradles with crying infants near the boulder where he was resting. He went over and began rocking the cradles to comfort the infants until they fell asleep. At midnight, two lights appeared on the top of the boulder and Muji heard two female voices asking him why he was there, so he informed them of his desperate situation. Since he couldn't see them in face, Muji asked about their identity and the nature of the dazzling lights. The two bright figures recognized Muji because they had often seen him in the pastures with his cows, thus they revealed to him that they were zanas. Subsequently, they granted Muji a wish for having taken care for the infants, offering him a choice between strength to be a mighty warrior, property and wealth, or knowledge and ability to speak other languages. Muji wished for strength to fight and beat the other cowherds who tease him. The zanas thus gave him their breasts. Muji drank three drops of milk and immediately felt strong enough to uproot a tree out of the ground. To test Muji's strength, the zanas asked him to lift the enormous heavy boulder that was near them, but he raised it only as high as his ankles. So the zanas gave him their breasts again and Muji drank until he was strong enough to raise the boulder over his head, becoming powerful like a Drangue. The zanas later proposed to him to become their blood brother, and Muji accepted. Afterwards the zanas took their cradles and disappeared; Muji instead woke up at daylight and departed in search of his cows. He found them and went back down into the Plain of Jutbina, where all the cowherds had already assembled. When they saw Muji coming, they began making fun of him, but this time he beat them. Muji abandoned the charge of his master and returned to his home. He started working for himself and went hunting up in the mountains. In later times Muji waged many battles and became a victorious hero.[47][50]

Main characters

[edit]

Muji and Halili cycle

[edit]- Mother of Muji and Halili

- Muji and Halili

- Omer

- Ajkuna

Gjergj Elez Alia legend

[edit]- Gjergj Elez Alia

- Sister of Gjergj Elez Alia

- Baloz

Songs of Palaj–Kurti's collection

[edit]- Gjeto Basho Muji

Martesa - Orët e Mujit

- Muji te Mbreti

- Martesa e Halilit

- Gjergj Elez Alija

- Muji e Behuri

Deka e Dizdar Osman agës me Zukun bajraktar - Fuqija e Mujit

- Fuqija e Halilit

- Gjogu i Mujit

Hargelja - Omeri i rí

- Zuku Bajraktár

- Bejlegu ndërmjet dy vllazënve të panjoftun

Arnaut Osmani e Hyso Radoica - Ali Bajraktari

B E S A - Martesa e Ali Bajraktarit

- Bani Zadrili

- Arnaut Osmani

- Ali Aga i rí

- Zuku mer Rushën

- Basho Jona

- Martesa e Plakut Qefanak

- Rrëmbimi i së shoqes së Mujit

- Muji e Jevrenija

- Halili merr gjakun e Mujit

- Siran Aga

- Halili i qet bejleg Mujit

- Omeri prej Mujit

- Deka e Hasapit

- Muji i rrethuem në kullë

- Deka e Omerit

- Ajkuna kján Omerin

- Deka e Halilit

- Muji i varruem

- Muji mbas deket

- Halili mbas deket

Songs of Elsie–Mathie-Heck's translation

[edit]- Mujo's Strength (n. 7 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Marriage of Mujo (n. 1 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Mujo's Oras (n. 2 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Mujo Visits the Sultan (n. 3 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Marriage of Halili (n. 4 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Gjergj Elez Alia (n. 5 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Mujo and Behuri (n. 6 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Mujo's Courser (n. 9 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Young Omeri (n. 10 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Zuku Bajraktar (n. 11 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Osmani and Radoica (n. 12 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Ali Bajraktari (n. 13 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Arnaut Osmani (n. 16 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Zuku Captures Rusha (n. 18 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Mujo's Wife Kidnapped (n. 21 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Mujo and Jevrenija (n. 22 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Halili Avenges Mujo (n. 23 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Omer, Son of Mujo (n. 26 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Death of Omer (n. 29 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Ajkuna Mourns Omer (n. 30 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Death of Halili (n. 31 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- Mujo Wounded (n. 32 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

- After Mujo's Death (n. 33 of Palaj-Kurti's coll.)

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Lord wrote the following of this endeavor:

"While in Novi Pazar, Parry had recorded several Albanian songs from one of the singers who sang in both languages. The musical instrument used to accompany these songs is the gusle (Albanian lahuta), but the line is shorter than the Serbian decasyllabic and a primitive type of rhyming is regular. It was apparent that a study of the exchange of formulas and traditional passages between these two poetries would be rewarding because it would show what happens when oral poetry passes from one language group to another which is adjacent to it. However, there was no sufficient time in 1935 to collect much material or to learn Albanian. While in Dubrovnik in the summer of 1937, I had an opportunity to study Albanian and in September and October of that year I traveled through the mountains of Northern Albania from Shkodër to Kukësi by way of Boga, Thethi, Abat, and Tropoja, returning by a more southerly route. I collected about one hundred narrative songs, many of them short, but a few between five hundred and a thousand lines in length. We found out that there are some songs common to both Serbo-Croatian and Albanian tradition and that a number of the Moslem heroes of the Yugoslav poetry, such as Mujo and Halili Hrnjica and Gjergj Elez Alia, are found also in Albanian. Much work remains to be done in this field before we can tell exactly what the relationship is between the two traditions."[43]

Sources

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Samson 2013, pp. 185–188; Miftari & Visoka 2019, pp. 238–241; Di Lellio & Dushi 2024.

- ^ Elsie 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Di Lellio & Dushi 2024.

- ^ Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. xv.

- ^ Jensen 1980, p. 114; Elsie, Songs of the Frontier Warriors; Miftari & Visoka 2019, pp. 238–241.

- ^ West 2007, p. 68; Elsie, Songs of the Frontier Warriors; Miftari & Visoka 2019, pp. 238–241; Di Lellio & Dushi 2024.

- ^ Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. xv; Elsie 2014, p. 1

- ^ Neziri & Scaldaferri 2016, p. 3; Elmer 2013, p. 4

- ^ Neziri & Scaldaferri 2016, p. 3.

- ^ Neziri 2001, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Elsie, Songs of the Frontier Warriors; Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. iii.

- ^ Scaldaferri 2021.

- ^ Vata-Mikeli 2023, pp. 429–431; Loria-Rivel 2020, pp. 45–46; Miftari & Visoka 2019, pp. 238–241; Leka 2018, pp. 118–120; Friedman 2012, p. 303; Neziri 2008, pp. 80–83; Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, pp. v, xvi; Prifti 2002, pp. 348–350; Elsie 2001, p. 183.

- ^ Loria-Rivel 2020, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Neziri 2021.

- ^ Vata-Mikeli 2023, pp. 429–431.

- ^ Loria-Rivel 2020, pp. 47–48, 52.

- ^ Loria-Rivel 2020, p. 52.

- ^ Friedman 2012, p. 303.

- ^ a b c d Neziri 2001, pp. 7–10.

- ^ a b Miftari & Visoka 2019, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 83, 164, 443.

- ^ Çabej 1968, p. 286.

- ^ Juka 1984, p. 64.

- ^ Neziri 2008, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Vata-Mikeli 2023, pp. 429–431; Poghirc 1987, pp. 178–179; Tirta 2004, pp. 68–82; Elsie 2001, pp. 181, 244.

- ^ Kondi 2017, p. 279.

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 63, 71, 112–117, 137–140, 163, 164, 191, 192.

- ^ Schirò 1959, p. 30–31.

- ^ a b Doja 2005, p. 459.

- ^ Doja 2005, p. 456.

- ^ a b Leka 2018, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Leka 2018, p. 120.

- ^ Doja 2005, p. 458.

- ^ Tirta 2004, p. 63.

- ^ a b Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. xi.

- ^ Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, pp. xi, xv.

- ^ Elsie 2014, p. 1.

- ^ a b Neziri & Scaldaferri 2016, p. 3.

- ^ a b Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. xii.

- ^ Elmer 2013, p. 4.

- ^ Ready 2018, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, pp. xii–xiii.

- ^ a b Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. xiii.

- ^ Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. xiv.

- ^ Neziri 2001, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Elsie, Songs of the Frontier Warriors.

- ^ Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. iii.

- ^ Elsie & Mathie-Heck 2004, p. viii.

- ^ Elsie 2001b, pp. 153–157.

Bibliography

[edit]- Çabej, Eqrem (1968). "Gestalten des albanischen Volksglaubens". In Manfred Mayrhofer (ed.). Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft und Kulturkunde: Gedenkschrift für Wilhelm Brandenstein 1898-1967. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft. Vol. 14. Auslieferung: Institut für Vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck. ISSN 0537-7250.

- Di Lellio, Anna; Dushi, Arbnora (2024). "Gender Performance and Gendered Warriors in Albanian Epic Poetry". In Lothspeich, Pamela (ed.). The Epic World. Routledge Worlds. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000912203.

- Doja, Albert (2005). "Mythology and Destiny" (PDF). Anthropos. 100 (2): 449–462. doi:10.5771/0257-9774-2005-2-449. JSTOR 40466549. S2CID 115147696.

- Dushi, Arbnora (May 2014). "On Collecting and Publishing the Albanian Oral Epic". Approaching Religion. 4: 37–44. doi:10.30664/ar.67535.

- Elmer, David (2013). "The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature". Oral Tradition. 28 (2): 341–354. doi:10.1353/ort.2013.0020. hdl:10355/65316. S2CID 162892594.

- Elsie, Robert (1994). Albanian Folktales and Legends. Naim Frashëri Publishing Company. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2009-07-28.

- Elsie, Robert (2001b). Albanian Folktales and Legends. Dukagjini Publishing House.

- Elsie, Robert (2001). A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology and Folk Culture. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 1-85065-570-7.

- Elsie, Robert; Mathie-Heck, Janice (2004). Songs of the Frontier Warriors. Wauconda, Illinois: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Incorporated. ISBN 0-86516-412-6.

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania (PDF). Historical Dictionaries of Europe. Vol. 75 (2 ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0810861886. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2014.

- Elsie, Robert (2014). "Why Is Albanian Epic Verse So Neglected?" (PDF). Paper Presented at the International Conference on the Albanian Epic of Legendary Songs in Five Balkan Countries: Albania, Kosova, Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro. Pristina: Institute of Albanian Studies.

- Elsie, Robert. "Songs of the Frontier Warriors". albanianliterature.net. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2012). "Balkan Epic Cyclicity: A View from the Languages". In P. Bohlman; N. Petković (eds.). Balkan Epic Song, History Modernity. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. pp. 293–309. ISBN 978-0810877993. S2CID 33042605.

- Jensen, Minna Skafte (1980). The Homeric Question and the Oral-formulaic Theory. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 8772890967.

- Juka, S. S. (1984), Kosova: The Albanians in Yugoslavia in Light of Historical Documents: An Essay, Waldon Press, ISBN 9780961360108

- Kolsti, John (1990). The Bilingual Singer: A Study in Albanian and Serbo-Croatian Oral Epic Traditions. Harvard dissertations in folklore and oral tradition. New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 0824028724.

- Kolsti, John (2021). "Milman Parry, Albert Lord, and the Albanian Epics". In Scaldaferri, Nicola (ed.). Wild Songs, Sweet Songs: The Albanian Epic in the Collections of Milman Parry and Albert B. Lord. Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature Series. Vol. 5. In collaboration with Victor Friedman, John Kolsti, Zymer U. Neziri. Harvard University, Center for Hellenic Studies. ISBN 9780674271333.

- Kondi, Bledar (2017). "Un regard critique sur l'ethnographie de la mort en Albanie". Ethnologie française. 166 (2): 277–288. doi:10.3917/ethn.172.0277.

- Leka, Arian (2018). "Motive shtegtare, elemente mitike dhe krijesa imagjinare në epikën shqiptare". Albanologjia – International Journal of Albanology (in Albanian) (9–10): 117–120. eISSN 2545-4919. ISSN 1857-9485.

- Loria-Rivel, Gustavo Adolfo (2020). "Dede Korkut and its Parallelisms with Albanian Epic Traditions. Female Warriors in Albanian and Turkic Epics". In Nikol Dziub, Greta Komur-Thilloy (ed.). Penser le multiculturalisme dans les marges de l'Europe. Studies on South East Europe. Vol. 26. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 45–53. ISBN 9783643912930.

- Miftari, Vehbi; Visoka, Avdi (2019). "The Hero of Great Deeds: From Albanian Songs of the Frontier Warriors to French Chansons de Geste". Journal of History Culture and Art Research. 8 (1): 237–242. doi:10.7596/taksad.v8i1.1761.

- Vata-Mikeli, Rovena (2023). "Shtresa mitologjike në kënget epike legjendare shqiptare, rasti i Eposit të Kreshnikëve". ALBANOLOGJIA International Journal of Albanology. 10 (19–20). University of Tetova: 428–431. eISSN 2545-4919. ISSN 1857-9485.

- Neziri, Zymer U. (2001). Xhevat Syla (ed.). Këngë të kreshnikëve. Libri Shkollor.

- Neziri, Zymer U. (2008). Institute of Albanology of Prishtina (ed.). Studime për folklorin: Epika gojore dhe etnokultura [The Study of Folklore: The Oral Epic and Ethnoculture]. Vol. II. Grafobeni.

- Neziri, Zymer U.; Scaldaferri, Nicola (2016), "From the Archive to the Field: New Research on Albanian Epic Songs", Conference: Singers and Tales in the 21st Century; The Legacies of Milman Parry and Albert Lord, Washington DC: Center for Hellenic Studies

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Neziri, Zymer U. (2021). "The Albanian Collection of Albert B. Lord in Northern Albania: Context, Contents, and Singers". In Scaldaferri, Nicola (ed.). Wild Songs, Sweet Songs: The Albanian Epic in the Collections of Milman Parry and Albert B. Lord. Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature Series. Vol. 5. In collaboration with Victor Friedman, John Kolsti, Zymer U. Neziri. Harvard University, Center for Hellenic Studies. ISBN 9780674271333.

- Pipa, Arshi (2017) [1982]. Aristea Kola, Lisandri Kola (ed.). "Rapsodë shqiptarë në serbokroatisht: cikli epik i kreshnikëve" (PDF). Kêns. Translated by Lisandri Kola: 25–79. ISSN 2521-7348.

- Poghirc, Cicerone (1987). "Albanian Religion". In Mircea Eliade (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 1. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. pp. 178–180.

- Prifti, Kristaq (2002). Instituti i Historisë (Akademia e Shkencave e RSH) (ed.). Historia e popullit shqiptar. Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime (in Albanian). Vol. 1. Botimet Toena. ISBN 9789992716229.

- Ready, Jonathan L. (2018). The Homeric Simile in Comparative Perspectives: Oral Traditions from Saudi Arabia to Indonesia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198802556.

- Samson, Jim (2013). Music in the Balkans. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-25038-3.

- Scaldaferri, Nicola, ed. (2021). Wild Songs, Sweet Songs: The Albanian Epic in the Collections of Milman Parry and Albert B. Lord. Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature Series. Vol. 5. In collaboration with Victor Friedman, John Kolsti, Zymer U. Neziri. Harvard University, Center for Hellenic Studies. ISBN 9780674271333.

- Schirò, Giuseppe (1959). Storia della letteratura albanese. Storia delle letterature di tutto il mondo (in Italian). Vol. 41. Nuova accademia.

- Tirta, Mark (2004). Petrit Bezhani (ed.). Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë (in Albanian). Tirana: Mësonjëtorja. ISBN 99927-938-9-9.

- Watkins, Calvert (1995). How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514413-0.

- West, Morris L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199280759.

Further reading

[edit]- Friedman, Victor (2021). "The Epic Admirative in Albanian". In Scaldaferri, Nicola (ed.). Wild Songs, Sweet Songs: The Albanian Epic in the Collections of Milman Parry and Albert B. Lord. Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature Series. Vol. 5. In collaboration with Victor Friedman, John Kolsti, Zymer U. Neziri. Harvard University, Center for Hellenic Studies. ISBN 9780674271333.

- SCHÜTZ, ISTVÁN (1985). "DES «COMANS NOIRS» DANS LA POÉSIE POPULAIRE ALBANAISE". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (in French). 39 (2/3): 193–203. JSTOR 23657607.

External links

[edit]- Songs of the Frontier Warriors (English translation by Elsie)

- "The Lord Albanian Collection, 1937" in the "Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature", Harvard University Libraries

- International Society for Epic Studies

- Mirash Ndou, Albanian singer of tales

- "Marriage of Halili" by the lahutar Isë Elezi-Lekëgjekaj