Portrayal of black people in comics

Black people have been portrayed in comics since the medium's beginning, with their portrayals often the subject of controversy.[1][2] Mainstream comic publishing companies have had a historical trend of being predominantly white and male, reflecting the lack of representation and inaccurate depictions of Black people in comics.[3] The integration of black characters in mainstream and superhero comics has endured various obstacles and challenges. Critics have noted that black men and women have historically often been portrayed as jungle or ghetto stereotypes, and as sidekicks as opposed to primary characters.[4][5][6] Occiasionally, comic book creators would lampshade stereotypes, lack of representation and emphasize social injustices.[7][8] In recent years, with the integration of more Black people in mainstream comic writing rooms as well as the creation of comics on digital platforms has changed the representation and portrayals of Black people in comics and has started to reflect the complexities of Black people across the diaspora.[2][9]

African characters[edit]

Cartoonist Lee Falk's adventure comic strip Mandrake the Magician featured the African supporting character Lothar from its 1934 debut. He was a former "Prince of the Seven Nations", a federation of jungle tribes, but passed on the chance to become king and instead followed Mandrake on his world travels, fighting crime. Initially an illiterate exotic garbed in animal skins, he provided the muscle to complement Mandrake's brain on their adventures. Lothar was modernized in 1965 to dress in suits and speak standard English.[10]

All-Negro Comics (June 1947) was a 15-cent omnibus written and drawn solely by African-American writers and artists. The feature starred characters that included the Lion Man, a young African scientist sent by the United Nations to oversee a massive uranium deposit at the African Gold Coast, whose main enemy was Doctor Blut Sangro.[11] Lion Man was meant to inspire black people's pride in their African heritage.[12]

In 1963, illustrator and musician Chris Acemandese Hall created Little Zeng, a young African king. Little Zeng is credited as the first black protagonist and also the first African comic book hero in the book "The Cultural/Political Movements of Harlem between 1960 and 1970: from Malcolm X to black is beautiful", organized by Klytus Smith. However, the character did not last long, as shortly after, Hall began to focus on his music career.[citation needed]

The series Powerman, designed as an educational tool, was published in 1975 by Bardon Press Features of London, England, for distribution in Nigeria. The series was written by Don Avenall (aka Donne Avenell) and Norman Worker, and illustrated by Dave Gibbons and Brian Bolland. In 1988, Acme Press republished the series in the UK for the first time, to capitalize on the popularity of the artists, both of whose careers had since taken off. Acme changed Powerman's name to Powerbolt to avoid confusion with the character Luke Cage, sometimes called Power Man, published by Marvel Comics. Powerman, who was super strong and could fly, appeared in stories rendered in a simple style reminiscent of Fawcett Comics' Golden Age Captain Marvel. His only apparent weakness was snakebite.[13]

In the larger framework of UNESCO's General History of Africa project (2012–2015), a series of open source comic books was used to support the creation of strong and positive African women role models; it was called The Women in African History e-learning platform. For the production of the comics stories available on the platform, UNESCO commissioned illustrators from France, Madagascar, Nigeria, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the United States. This project aimed to highlight illustration and graphic arts in Africa and constituted a springboard for the young artists involved:

- Y. Sanders (U.S.) — illustrator of the comic strip on Sojourner Truth

- Sleeping Pop (Madagascar) — illustrator of the comic strip on Gisèle Rabesahala

- Alaba Onajin (Nigeria) — illustrator of the comic strips on Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and Taytu Betul

- Eric Muthoga (Kenya) — illustrator of the comic strip on Wangari Maathai

- Pat Masioni (Congo) — illustrator of the comic strips on Nzinga Mbandi and the Women Soldiers of Dahomey

- Yann Degruel (France) — Illustrator of the comic strips on Yennega and the Mulatto Solitude

All-Negro Comics[edit]

All-Negro Comics No. 1, published out of Philadelphia in mid-1947, was the first known comics magazine written and drawn solely by African-American writers and artists. In describing lead feature "Ace Harlem", Time magazine wrote, "The villains were a couple of zoot-suited, jive-talking Negro muggers, whose presence in anyone else's comics might have brought up complaints of racial 'distortion.' Since it was all in the family, publisher Orrin C. Evans thought no Negro readers would mind."[11] The protagonist of "Ace Harlem", however, was a highly capable African-American police detective.[12]

1956: Comics Code Authority tries to censor "Judgment Day"[edit]

In the 1950s the portrayal of a black man in a position of authority and a discussion of racism in a comic was at the center of a battle between Entertaining Comics editor William Gaines and the Comics Code Authority, which had been set up in 1954 to self regulate the content of US comics amid fears they were a corrupting influence on youth. Gaines fought frequently with the CCA in an attempt to keep his magazines free from censorship. The particular example noted by comics historian Digby Diehl, Gaines threatened Judge Charles Murphy, the Comics Code Administrator, with a lawsuit when Murphy ordered EC to alter the science-fiction story "Judgment Day", in Incredible Science Fiction No. 33 (Feb. 1956).[14] The story, by writer Al Feldstein and artist Joe Orlando, was a reprint from the pre-Code Weird Fantasy No. 18 (April 1953), inserted when the Code Authority had rejected an initial, original story, "An Eye For an Eye", drawn by Angelo Torres[15] but was itself also "objected to" because of "the central character being black."[16]

The story depicted a human astronaut, a representative of the Galactic Republic, visiting the planet Cybrinia inhabited by robots. He finds the robots divided into functionally identical orange and blue races, one of which has fewer rights and privileges than the other. The astronaut decides that due to the robots' bigotry, the Galactic Republic should not admit the planet. In the final panel, he removes his helmet, revealing himself to be a black man.[14] Murphy demanded, without any authority in the Code, that the black astronaut had to be removed. As Diehl recounted in Tales from the Crypt: The Official Archives:

This really made 'em go bananas in the Code czar's office. 'Judge Murphy was off his nut. He was really out to get us', recalls [EC editor] Feldstein. 'I went in there with this story and Murphy says, "It can't be a Black man". But ... but that's the whole point of the story!' Feldstein sputtered. When Murphy continued to insist that the Black man had to go, Feldstein put it on the line. 'Listen', he told Murphy, 'you've been riding us and making it impossible to put out anything at all because you guys just want us out of business'. [Feldstein] reported the results of his audience with the czar to Gaines, who was furious [and] immediately picked up the phone and called Murphy. 'This is ridiculous!' he bellowed. 'I'm going to call a press conference on this. You have no grounds, no basis, to do this. I'll sue you'. Murphy made what he surely thought was a gracious concession. 'All right. Just take off the beads of sweat'. At that, Gaines and Feldstein both went ballistic. 'F**k you!' they shouted into the telephone in unison. Murphy hung up on them, but the story ran in its original form.[17]

Feldstein, interviewed for the book Tales of Terror: The EC Companion, reiterated his recollection of Murphy making the request:

So he said it can't be a Black [person]. So I said, 'For God's sakes, Judge Murphy, that's the whole point of the Goddamn story!' So he said, 'No, it can't be a Black'. Bill [Gaines] just called him up [later] and raised the roof, and finally they said, 'Well, you gotta take the perspiration off'. I had the stars glistening in the perspiration on his Black skin. Bill said, 'F**k you', and he hung up.[18]

Although the story would eventually be reprinted uncensored, the incident caused Gaines to abandon comic books and concentrate on Mad magazine, which was EC's only profitable title.[17]

Non-fiction portrayals[edit]

In the late 1940s, Parents Magazine Press published two issues of Negro Heroes, which reprinted stories about such historical figures as Joe Louis, George Washington Carver, Paul Robeson, and Charles L. Thomas. In 1950 Fawcett Comics produced three issues of Negro Romance, which was notable for its eschewing of African-American stereotypes, telling stories interchangeable with those told about white characters. Fawcett also published short-lived ongoing titles featuring Joe Louis[19] and Jackie Robinson.[20]

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story was a 16-page comic book about Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and the Montgomery bus boycott published in 1957 by the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR USA).[21] Although ignored by the mainstream comics industry, The Montgomery Story was widely distributed among civil rights groups, churches, and schools. It helped inspire nonviolent protest movements around the Southern United States, and later in Latin America, South Africa,[22] the Middle East, and elsewhere. Over 50 years after its initial publication, the comic inspired the best-selling, award-winning March trilogy by Georgia Congressman John Lewis.[21]

The final issue of Classics Illustrated, published in 1969, featured "Negro Americans: The Early Years", with biographical sketches of Crispus Attucks, black Revolutionary War and Civil War soldiers, Benjamin Banneker and Phillis Wheatley, James Beckwourth, the Buffalo Soldiers, Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, Harriet Tubman, Elijah McCoy, Garrett Morgan, Granville Woods, Matthew Henson, and Dr. Daniel Hale Williams; as well as stories about the Underground Railroad and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.[23]

Fitzgerald Publishing Co. produced the Golden Legacy line of 16 educational black history comic books from 1966 to 1976. In many ways modeled after Classics Illustrated, Golden Legacy produced biographies of such notable figures as Harriet Tubman, Crispus Attucks, Benjamin Banneker, Matthew Henson, Alexandre Dumas, Frederick Douglass, Robert Smalls, Joseph Cinqué, Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King Jr., Alexander Pushkin, Lewis Howard Latimer, and Granville Woods. Golden Legacy was the brainchild of African American accountant Bertram Fitzgerald, who also wrote seven of the volumes. Many of the other contributors to the Golden Legacy series were also black, including Joan Bacchus and Tom Feelings. Other notable contributors included Don Perlin and Tony Tallarico.[24]

First African-American solo series[edit]

In 1950, the Pittsburgh Courier published the Western comic strip Chilsom Kid by Carl Pfeufer.[25]

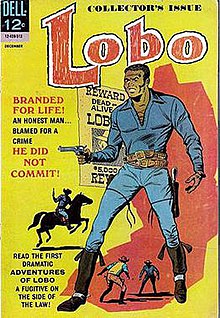

Lobo was a fictional Western comic book hero who was the medium's first African-American character to headline his own series. He starred in Dell Comics' little-known two-issue series Lobo (Dec. 1965 and Sept. 1966), was created by D. J. Arneson and Tony Tallarico.[26]

In 1970, Larry Fuller's black superhero Ebon appeared in one issue of his own comic, published by the underground comix publisher San Francisco Comic Book Company.[27] Ebon was a bad fit with the largely white, adult audiences of underground comix, and did not meet with much success.[28]

From January 18, 1970, to February 17, 1974, was published the comic strip Friday Foster, created and written by Jim Lawrence and later continued by Jorge Longarón.[29] In 1975, Friday Foster was adapted into a blaxploitation feature film of the same name, starring Pam Grier.

DC and Marvel's black starring characters[edit]

In the 1940s, the only black character to appear in Timely Comics (predecessor to Marvel) was literally named "White-Wash" and looked like a young white boy in black face rather than an actual African American character. The character starred in Timely's Young Allies, a book about a "kid gang" who, led by Captain America's sidekick Bucky Barnes and the Human Torch's sidekick Toro, battle the Nazi menace.[30]

While Marvel Comics' 1950s predecessor Atlas Comics had published the African tribal-chief feature "Waku, Prince of the Bantu"—the first known mainstream comic-book feature with a Black star, albeit not African-American. Waku was one of four regular features in each issue of the omnibus title, Jungle Tales (Sept. 1954 – Sept. 1955).

Two early Westernized, non-stereotyped African-American supporting characters in comic books are World War II soldier Jackie Johnson, who integrated the squad, Easy Company, when introduced as the title character of the story "Eyes for a Blind Gunner" in DC Comics' Our Army at War No. 113 (Dec. 1961) by writer Bob Kanigher and artist Joe Kubert;[31] Marvel Comics' first African-American supporting character, World War II soldier Gabe Jones, of an integrated squad in Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos No. 1 (May 1963). The character of African-American scientist Bill Foster appeared in The Avengers No. 32 (Sep. 1966) to No. 35, and again in No. 41, #54 and No. 75. The Amazing Spider-Man introduced the African-American supporting characters Joe Robertson, editor of a major newspaper, in 1967; his son Randy in 1968, and Hobie Brown (The Prowler) in 1969.

The first black superhero in mainstream American comic books is Marvel's the Black Panther, an African who first appeared in Fantastic Four No. 52 (July 1966). He was originally conceived by Jack Kirby as a character named "Coal Tiger".[32] This was followed by the first African-American superhero in mainstream comics, the Falcon, introduced in Captain America No. 117 (Sept. 1969). Following Kirby's Black Racer, a paralyzed Vietnam War veteran who became the avatar of death for DC's New Gods (New Gods No. 3, July 1971), DC introduced John Stewart, an architect who becomes Hal Jordan's new backup Green Lantern in Green Lantern No. 87 (Jan. 1972).[33] By resisting a suggestion to name the character Lincoln Washington (a stereotypical slave name), artist Neal Adams struck a blow for diversity at DC.[33]

There would be no black hero starring in his or her own mainstream comic title until Marvel's Luke Cage debuted in his own title, Luke Cage, Hero for Hire, in June 1972. Following this, Black Panther took over the title Jungle Action from issue No. 5, beginning with a reprint of the Panther-centric story from The Avengers No. 62 followed by a new, critically acclaimed series written by Don McGregor with art by pencilers Rich Buckler, Gil Kane, and Billy Graham, in #6–24 (Sept. 1973 – Nov. 1976). Meanwhile, Luke Cage's title saw supporting character Bill Foster become Black Goliath in April 1975, and the following month saw the debut of Marvel's first major African female character, the superhero Storm of the X-Men in Giant-Size X-Men No. 1 (May 1975).

DC Comics' first black superhero to star in his own series was Black Lightning. He debuted in his self-titled series in April 1977.[33] He was Jefferson Pierce, an Olympic athlete turned inner-city school teacher.[33] Created by Tony Isabella and artist Trevor Von Eeden, he toted a voltage-generating belt and a white mask. He was followed in January 1973 by the debut of the Amazon warrior Nubia (Wonder Woman's long lost fraternal twin sister) in Wonder Woman #204, marking the first appearance of a Black woman superhero character in a DC Comics publication. DC's young superhero team the Teen Titans saw supporting character Mal Duncan, who first appeared in Teen Titans No. 26 in 1970, become the superhero Guardian in Teen Titans No. 44 (Nov. 1976). He was quickly joined by Bumblebee (appearing from Teen Titans No. 46 as Karen Beecher, and from No. 48, June 1977, as Bumblebee). Three years later, the formation of the New Teen Titans would see the introduction of Victor Stone as the superhero Cyborg (DC Comics Presents No. 26, Oct. 1980). Created by writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Pérez, Cyborg would later have his own title and has more recently been a member of the Justice League.

Ethnic stereotypes[edit]

The earliest black character to appear in his own (American) comic strip was Pore Li'l' Mose (1900) by Richard F. Outcault.[34] In Frank King's Bobby Make-Believe the African-American housemaid Rachel made her debut, whom he would later reintroduce in his more famous comic strip Gasoline Alley. While Rachel was a stereotypical Mammy archetype character she was still portrayed as an intelligent and self-assured character with just as much backstory as all the other (white) characters. Back in the day, The Chicago Defender and New York Amsterdam News, which aimed at African-American readers, both praised her as positive rolemodel for the black population.[35] Ken Kling's comic strip Joe and Asbestos (1924–1925) featured a black sidekick named Asbestos.[36]

The first black character to be incorporated into a syndicated comic strip was Lothar who appeared in Mandrake the Magician in the 1930s. He was Mandrake's sidekick: the circus strongman, who wore a Tarzan-style costume, was drawn in the Sambo-style of the time (see below) and was poor, and uneducated.[10][37] Since the introduction of Lothar, Black characters have received a variety of treatments in comics, not all of them positive. William H. Foster III, associate professor of English at Naugatuck Valley Community College said, "they were comic foils, ignorant natives or brutal savages or cannibals".[37]

Writer-artist Will Eisner was sometimes criticized for his depiction of Ebony White, the young African American sidekick of Eisner's 1940s and 1950s character The Spirit. Eisner later admitted to consciously stereotyping the character, but said he tried to do so with "responsibility", and argued that "at the time humor consisted in our society of bad English and physical difference in identity".[38] The character developed beyond the stereotype as the series progressed, and Eisner also introduced black characters (such as the plain-speaking Detective Grey) who defied popular stereotypes. In a 1966 New York Herald Tribune feature by his former office manager-turned-journalist, Marilyn Mercer wrote, "Ebony never drew criticism from Negro groups (in fact, Eisner was commended by some for using him), perhaps because, although his speech pattern was early Minstrel Show, he himself derived from another literary tradition: he was a combination of Tom Sawyer and Penrod, with a touch of Horatio Alger hero, and color didn't really come into it".[39]

Physical caricatures[edit]

Early graphic art of various kinds often depicted black characters in a stylized fashion, emphasizing certain physical features to form a recognizable racial caricature of black faces. These features often included long unkempt hair, broad noses, enormous, red-tinted lips, dark skin and ragged clothing reminiscent of those worn by African American slaves. These characters were also depicted as speaking accented English. In the early 20th century United States, these kinds of representations were seen frequently in newspaper comic strips and political cartoons, as well as in later comic magazines, and were also present in early cartoons by Disney and Looney Tunes.

In comics, nameless black bystanders (see right) and even some notable heroes and villains were developed in this style, including Ebony White (see above), and Steamboat, valet of Billy Batson. In erotic comics, blacks are at times portrayed as hypersexual, and accompanying physical features such as a macrophallic penis in black men.[40] Robert Crumb's underground comix character Angelfood McSpade, introduced in 1967, embodied all of these qualities.[41] Crumb intended the character to be critical of the racist stereotype itself and assumed that the young liberal hippie/intellectual audience who read his work were not racists, and that they would understand his intentions for the character.[42][43] Nonetheless, in the face of accusations of racism and sexism,[44] Crumb retired the character after 1971.

Blaxploitation era[edit]

In the late-1960s and throughout the 1970s, several African-American heroes were created in the vein of Blaxploitation-era movie protagonists, and seemed to be a direct response to the notable Black Nationalist movement. These predominantly male heroes were often martial artists, came from the ghetto, and were politically motivated. Examples of such Blaxploitation characters include Luke Cage, Bronze Tiger, Black Lightning, and the female detective Misty Knight.[45] The Falcon stars in one infamous story arc in the Captain America series, in which he is portrayed as a street hustler before being "rescued" by Captain America.[30]

Inspired by Blaxploitation esthetics, Real Deal Magazine was an independent comic book title published in the 1990s. One of the rare contemporary African-American-created and published comics, Real Deal depicted Los Angeles underworld life with deadpan visceral humor and gross-out violence (termed "Urban Terror" by the creators).[citation needed]

Black female characters[edit]

Until 1957, racial segregation laws existed that prevented Black comic writers and illustrators from working in mainstream comic studios.[46] Due to the lack of representation Black women were hardly represented in comics, and when they were, they were portrayed as typical stereotypes attributed to Black women like the Jezebel, the Mammy and the Sapphire as well as jungles stereotypes or of Africans that needed saving.[3][47][5] Despite not being able to work in white publishing houses Black creators still created comics for Black Newspapers where they were able to portray themselves as they saw fit.[46][48] Jackie Ormes was the first African American women cartoonist to be published. In 1937 she created one of the first female-led comic strips called Torchy Brown from Dixie to Harlem for the Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper. Ormes depicted the Black women in her comics after herself and the women around her. Her characters lived similar lives Black women during the time. Ormes was able to expand the portrayal of her Black female characters outside of the stereotypes that they were often seen in. Her characters redefined womanhood and Blackness, and touched on controversial topics of racism, sexism, and classism.[48][49][46]

The 1970s is when Black women started to make a more recurring role into mainstream comics, with their introduction into superhero comics.[48][9] Very few Black female characters were present in superhero comics before the Civil Rights Movement. Afterwards, several notable Black female characters began to appear. While Black women were introduced to mainstream comics as a way to draw in a more diverse group of readers, they were often still portrayed with historical stereotypes but in an updated way.[3][47] Two of the most notable Black female characters in comics appeared in the Bronze Age of Comic Books: Marvel Comics' Storm and DC Comics' Nubia. Storm (Ororo Munroe) of the X-Men is introduced as being worshiped as an African goddess; Professor Xavier quickly reveals her to be a mutant who possesses the power to control the weather. Later it is revealed that her parents were killed when she was very young, and she grew up as a thief on the streets of Cairo. Storm would eventually succeed Cyclops as the team leader of the X-Men.[50] Nubia is introduced as Wonder Woman's long-lost fraternal twin, and is historically DC Comics' first Black woman superhero character. This distinction is also sometimes accorded to the Teen Titan Bumblebee, a more traditional comic book costumed crimefighter, who debuted in 1976, four years after Nubia's first appearance.[51]

The first Black female character introduced from a major publishing house was Storm.[3] While her arrival allowed for people who identify with her to be represented in comics, her character was still subject to the stereotypical archetypes used to portray Black women. In her first appearance into the X-Men comic her body was over sexualized and she was made to seem like a primitive compared to her X-Men counterparts. She was illustrated wearing tight fitting clothing where her breasts were the made main focus of her appearance. Her character was also seen to be more combative and rebellious then her white female counterparts, as storm was reluctant to being considered a mutant as well as having to join the X-Men.[9] Nubia's character was also subjected similar portrayals, while also falling in to the shadow of Wonder Women her sister.[3] Nubia and Wonder Women had the same abilities yet she was never received a large role in any of the stories. While charters like Storm and Nubia were written and illustrated with stereotypical archetypes for Black women. Characters like Amanda Waller strayed away from those stereotypes allowing for a more diverse representation of Black women in comics. Introduced to DC comics in the 1980s, Wallers character broke barriers of representation by receiving a higher education and holding a position of power by being an elected official. She is the creator of the Suicide Squad also called Task Force X, where she leads the team to help save not only her community but the world.[5]

In the 1980s, the new Captain Marvel, aka Monica Rambeau, had the power to become any form of energy on the electromagnetic scale. This Captain Marvel would join the Avengers in their battle against the Masters of Evil.[52] In 1991, Captain Confederacy became one of the first female black superheroes to have her own series, published by Marvel's Epic Comics imprint.

There are those who have criticized black superheroines for being one-dimensional and perpetuating several stereotypes, including that of the mythical superwoman and the hyper-emotional, overly aggressive Black woman.[53]

While Black female characters have continued to gain space in mainstream comics, it has been a slow transition. However, with the introduction of digital platforms for publishing comic, more people have been able to create comics that have positive representations of Black women and showcase their diverseness.[9] Comics like Bitch Planet and Marvel's Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur showcase Black women and girls in a different light and tackle issue surrounding their women and girlhood. In the comic Bitch Planet, Penny Rolle is a character fighting against the Fatherhood State in charge of the Planet. Her character is a queer Black women, whose body has not sex appeal and her physical body usually exceeds the frame of the comic. Penny's fight against the authority figures is used to symbolize women's fight against patriarchy. Bitch Planet allows a glimpse of how different Black women navigate the world's their in. In Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur, Lunella Lafayette is a nine year old little Black girl who is also a genius. The comic navigates her life as a little girl who is able to switch brains with her sidekick Devil Dinosaur. This comic opens the door for readers of a younger age group, allowing them to find representations that they identify with. Comics like these shows the changes in the portrayal of Black female characters in comics in an expansive way.[2]

Milestone Media[edit]

Milestone Media was a company founded in 1993 by African-American artists and writers Dwayne McDuffie, Denys Cowan, Michael Davis, and Derek T. Dingle. The company's focus was to make multi-ethnic characters the stars of their monthly titles. Although Milestone comics were published through DC Comics, they did not take place in the DC Universe. The Milestone characters existed in a separate continuity that did not fall under DC Comics' direct editorial control (but DC still retained right of refusal to publish).

Milestone had several advantages in its publishing efforts: the company received press coverage from non-comics related magazines and television, its books were distributed and marketed by DC Comics, the comics industry had experienced remarkable increases in sales in preceding years, Milestone featured the work of several well-known and critically acclaimed creators, and it had the potential to appeal to an audience that was not being targeted by other publishers.

Milestone provided the opportunity for many emerging talents who had been passed over by larger established companies, launching the careers of many comic industry professionals; among them are John Paul Leon, Christopher Sotomayor, Christopher Williams (aka ChrisCross), Shawn Martinbrough, Tommy Lee Edwards, Jason Scott Jones (aka J.Scott.J), Prentis Rollins, J.H. Williams III, Humberto Ramos, John Rozum, Eric Battle, Joseph Illidge, Madeleine Blaustein, Jamal Igle, Chris Batista, and Harvey Richards.

21st century[edit]

- In 2000, Christopher Priest wrote a new Black Panther series. One of the highlights of Priest's run was his storyline "Enemy of the State".[54] The Panther becomes a symbol of a larger African American community dealing with white supremacist violence. Priest even spoofs the old comics convention of bringing in black characters as an exotic supporting cast for the white superheroes with the Avengers appearing in the title.[30] The gist of the most recent[when?] Black Panther series is that focuses on the African nation that T'Challa leads.

- In 2006, Ororo married fellow African superhero the Black Panther. Collaborating writer Eric Jerome Dickey explained that it was a move to explicitly target the female and African American audience.[55] Marvel Comics editor-in-chief Joe Quesada was highly supportive of this marriage, stating it was the Marvel Comics equivalent of the marriage of "Lady Diana and Prince Charles", and he expected both characters to emerge strengthened.[56]

- Kansas cartoonist Alonzo Washington is the creator of Omega Man, a self-published title about a socially conscious African-American comic book superhero who concentrates on positive, ethical values. Part of the focus includes addressing school shootings and youth violence that is affecting America. The focus was executed as a free web comic published on the official Omega Man website.[57] As a public service, Washington's comics came with trading cards each with an image of a missing child.[58] Washington would see stories of missing black children in the local press but did not see them nationally. "Instead of just complain about it, I wanted to do something to change that and also raise the issue." said Washington.[59]

- Marvel Comics published the 2004 series Truth: Red, White & Black. It recounted the untold story of Isaiah Bradley, the second Captain America, an African American soldier who endured brutal tests that echoed the real-life Tuskegee syphilis experiments that were conducted starting in the 1930s on a group of American men who were black and poor.[33]

- In November 2005, Nelson Mandela announced that the comic book A Son of the Eastern Cape would provide an illustrated history of Mandela's formative years, starting with his birth. The opening panels show Mandela as a swaddled baby in his parents' arms in their mud hut in the village of Mwezo, near Qunu in the Eastern Cape. The book was scheduled to consist of 26 volumes, written and illustrated by Nic Buchanan, and to be translated into South Africa's 10 other official languages. A teacher's guide was also to be created.[60]

- In 2005, Marvel Comics mounted a high-profile relaunch of a title starring their marquee black hero, the Black Panther. The series debuted in February – Black History Month – and landed at No. 27 spot on the monthly bestselling comics list.[33]

- In 2006, DC Comics unveiled a new generation of heroes that were minorities. As part of a larger shake-up of the DC Universe, tying into stories such as 52, "One Year Later" and Countdown to Final Crisis, DC introduced an African American version of Firestorm.[33]

- In 2010, comic book creator Nicholas Da Silva published Dread & Alive, a series that introduced the first Jamaican superhero as its protagonist, Drew McIntosh. Published under his artist name, ZOOLOOK, the series debuted on February 6 and included a reggae soundtrack with each issue.

- In 2012, Eritrean-Norwegian comic book creator published The Urban Legend, a series which focuses on a black superhero who combats streetcrime.[61] Yohannes created the series because he felt black children needed superheroes who looked like them to look up to.[62]

See also[edit]

- African characters in comics

- List of black animated characters

- List of black superheroes

- East Coast Black Age of Comics Convention

- Ethnic stereotypes in comics

- Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, 1957

- March, a trilogy by John Lewis (2013, 2015, 2016)

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Black Representation in Comics · Spectacular Blackness · WUSTL Digital Gateway Image Collections & Exhibitions".

- ^ a b c Collins, Alyssa (January 9, 2017). "When It Ain't Broke: Black Female Representation in Comics". AAIHS. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Representation of Black Women in Comics Matters". Refract Magazine. April 18, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Jeffrey (2001). Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics and Their Fans. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. p. 5. ISBN 1578062829.

- ^ a b c Gipson, Grace (2019). "The Power of a Black Superheroine: Exploring Black Female Identities in Comics and Fandom Culture" (PDF). EScholarship.

- ^ Marshall, Laticia (2019). "Representations of Women and Minorities Groups in Comics". San Jose State University ScholarWorks. doi:10.31979/etd.tqqb-445h.

- ^ "Introduction to Superman's Girlfriend Lois Lane: I Am Curious (Black)! · Spectacular Blackness · WUSTL Digital Gateway Image Collections & Exhibitions".

- ^ Chute, Hillary (June 16, 2020). "Superman Returns, to Beat Up the Klan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Schwein, Uncultured (September 3, 2020). "The Comic Book Future is Black and Female". Medium. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "Afros, Icons, and Spandex: A Brief History of the African American Superhero". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Press: Ace Harlem to the Rescue". Time. July 14, 1947. Archived from the original on April 24, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Christopher, Tom (2002). "Orrin C. Evans and the story of All-Negro Comics". TomChristopher.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2011. Reprinted from Comics Buyer's Guide February 28, 1997, pp. 32, 34, 37–38. Article includes reprinted editorial page "All-Negro Comics: Presenting Another First in Negro History" from All-Negro Comics #1

- ^ "Reading Room Index to Comic Art Collection: "Nigel" to "Night Out"". Archived from the original on June 15, 2006.

- ^ a b Lundin, Leigh (October 16, 2011). "The Mystery of Superheroes". Orlando: SleuthSayers.org.

- ^ "GCD :: Issue :: Incredible Science Fiction #33". Comics.org. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Don & Maggie, "Crack in the Code", Newfangles No. 44, February 1971

- ^ a b Diehl, Digby. Tales from the Crypt: The Official Archives (St. Martin's Press, New York, NY 1996) p 95

- ^ Von Bernewitz, Fred and Grant Geissman. Tales of Terror: The EC Companion (Gemstone Publishing and Fantagraphics Books, Timonium, Maryland and Seattle, Washington, 2000), p. 88

- ^ Joe Louis: Champion of Champions, Grand Comics Database. Accessed February 29, 2016.

- ^ Jackie Robinson, Grand Comics Database. Accessed February 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Bello. Grace. "A Comic Book for Social Justice: John Lewis," Publishers Weekly (July 19, 2012).

- ^ Aydin, Andrew (August 1, 2013). "The comic book that changed the world: Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story's vital role in the Civil Rights Movement". Creative Loafing (Atlanta). Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ "Classics Illustrated #169 [O] – Negro Americans The Early Years," Grand Comics Database. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- ^ Christopher, Tom. "Bertram A Fitzgerald and the Golden Legacy Series of Black History Comics" (originally published in edited form in Comics Buyer's Guide), TomChristopher.com (2004).

- ^ Vintage Black Heroes – The Chisholm Kid

- ^ Fisher, Stuart (February 21, 2018). "Those Unforgettable Super-Heroes of Dell & Gold Key". Alter Ego. No. 151. TwoMorrows Publishing.

- ^ McCabe, Caitlin. "Profiles in Black Cartooning: Larry Fuller," Comic Book Legal Defense Fund website (February 17, 2016).

- ^ Rifas, Leonard. "Racial Imagery, Racism, Individualism, and Underground Comix," ImageTexT (2004). Accessed April 14, 2009.

- ^ Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780472117567.

- ^ a b c Poole, W. Scott (April 27, 2005). "CATFISH ROW: Superman in the Cotton Fields: Comics in Black and White, Mostly White". Pop Matters. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ^ "GCD :: Issue :: Our Army at War #113". Comics.org. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ "Title TK". Oddball Comics. February 3, 2006. Archived from the original on May 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Hero deficit: Comic books in decline | Toronto Star". Thestar.com. March 18, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ "Don Markstein's Toonopedia: Pore Lil Mose".

- ^ "Frank O. King".

- ^ "Ken Kling".

- ^ a b Dotinga, Randy. "Coloring the Comic Books". Wired. Archived from the original on November 14, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Arnold, Andrew D. "Never Too Late". Time. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ^ Mercer, Marilyn, "The Only Real Middle-Class Crimefighter", New York (Sunday supplement, New York Herald Tribune), January 9, 1966; reprinted Alter Ego No. 48 (see under References below)

- ^ Padva, Gilad. "Dreamboys, meatmen and werewolves: Visualizing erotic identities in All-Male comic strips." Sexualities 8.5 (2005): 587–599.

- ^ Dowd, Douglas B.; Hignite, Todd (2006). Strips, Toons, And Bluesies: Essays In Comics And Culture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, pp. 76–79. ISBN 978-1-56898-621-0.

- ^ Crumb, R.; Holm, D. K. (2004). R. Crumb: Conversations. Conversations With Comic Artists series. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi., pp. vi–viii, xvi, 31–33, 120–121, 164, 166. ISBN 978-1-57806-637-7.

- ^ Lopes, Paul (2009). Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-1-59213-443-4.

- ^ Sorensen, Lita (2005). Bryan Talbot: The Library of Graphic Novelists. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-4042-0282-5.

- ^ "Black Power or Blaxploitation?: On Black Lightning's Afro Wig and Black Heroes in the Comics". Archived from the original on March 17, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Blog: Early Black Comic Book Writers, Illustrators, and Newspaper Cartoonists". Free Library of Philadelphia. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Marshall, Laticia (2019). "Representations of Women and Minorities Groups in Comics". San Jose State University ScholarWorks. doi:10.31979/etd.tqqb-445h.

- ^ a b c "The History of Black Female Superheroes Is More Complicated Than You Probably Think". Time. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "Her Comics were Everything Jim Crow America Never Wanted Black Women to Be". Messy Nessy Chic. March 18, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Uncanny X-Men No. 201

- ^ "Little Known Black History Fact: Nubia, The Black Wonder Woman". June 9, 2017.

- ^ The Avengers #273–277

- ^ Lynne d Johnson (December 1, 2003). "Black Thoughtware". PopMatters. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008.

- ^ Black Panther #6–12

- ^ "Black Panther/Storm wedding conference". Archived from the original on November 23, 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ^ Quesada, Joe. "Joe's Friday 31, a weekly Q&A with Joe Quesada". Archived from the original on November 23, 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ^ "Omega 7 Fatty Acids | Palmitoleic Acid | Sibu Beauty". Omega7.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ "Signifying Science". Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ "CNN.com – Transcripts". Transcripts.cnn.com. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ "Mandela: comic book hero". SouthAfrica.info. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ Truitt, Brian. "'The Urban Legend' fights crime on the mean streets". USA TODAY. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Yohannes, Josef (May 29, 2015). "Vi trenger Malcolm Tzegai Madiba". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved February 18, 2020.

Sources[edit]

- Gateward, Frances, ed. The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics and Sequential Art (Rutgers University Press, 2015) ISBN 978-0813572338

- Strömberg, Fredrik. Black Images in the Comics: a Visual History (Fantagraphics Books, 2003) ISBN 978-1560975465

External links[edit]

- Daathrekh.com

- The Milestone Rave – lists details of 264 Milestone comics issues

- The Official website of Dwayne McDuffie, co-owner of Milestone Media.

- Milestone: Finally, I was there – an article detailing Christopher Priest's role in the creation of Dakotaverse and his involvement with Milestone in general.

- Milestone retrospective at Museum of Black Superheroes

- Milestone Character profiles at Museum of Black Superheroes

- Omega Man comic on Anti-Gang Violence