by Zak Stone

October 14, 2015 Photo by: Mark Peaced

GoldLink: "Dance on Me" (via SoundCloud)

“If it sounds too new, then tomorrow, it will sound like yesterday,” Rick Rubin tells his mentee GoldLink during a critical listening session for the D.C. rapper’s upcoming debut album, And After That, We Didn’t Talk. “But this has a new, timeless feeling, which is the best of all combinations.” The 52-year-old producer is famous for these types of mystically earnest expressions about music—koans that would not mean much if they didn’t come from a guy who played an essential role in popularizing the artform of hip-hop and has creatively guided the likes of Johnny Cash, Beastie Boys, Adele, and Kanye West over the last three decades.

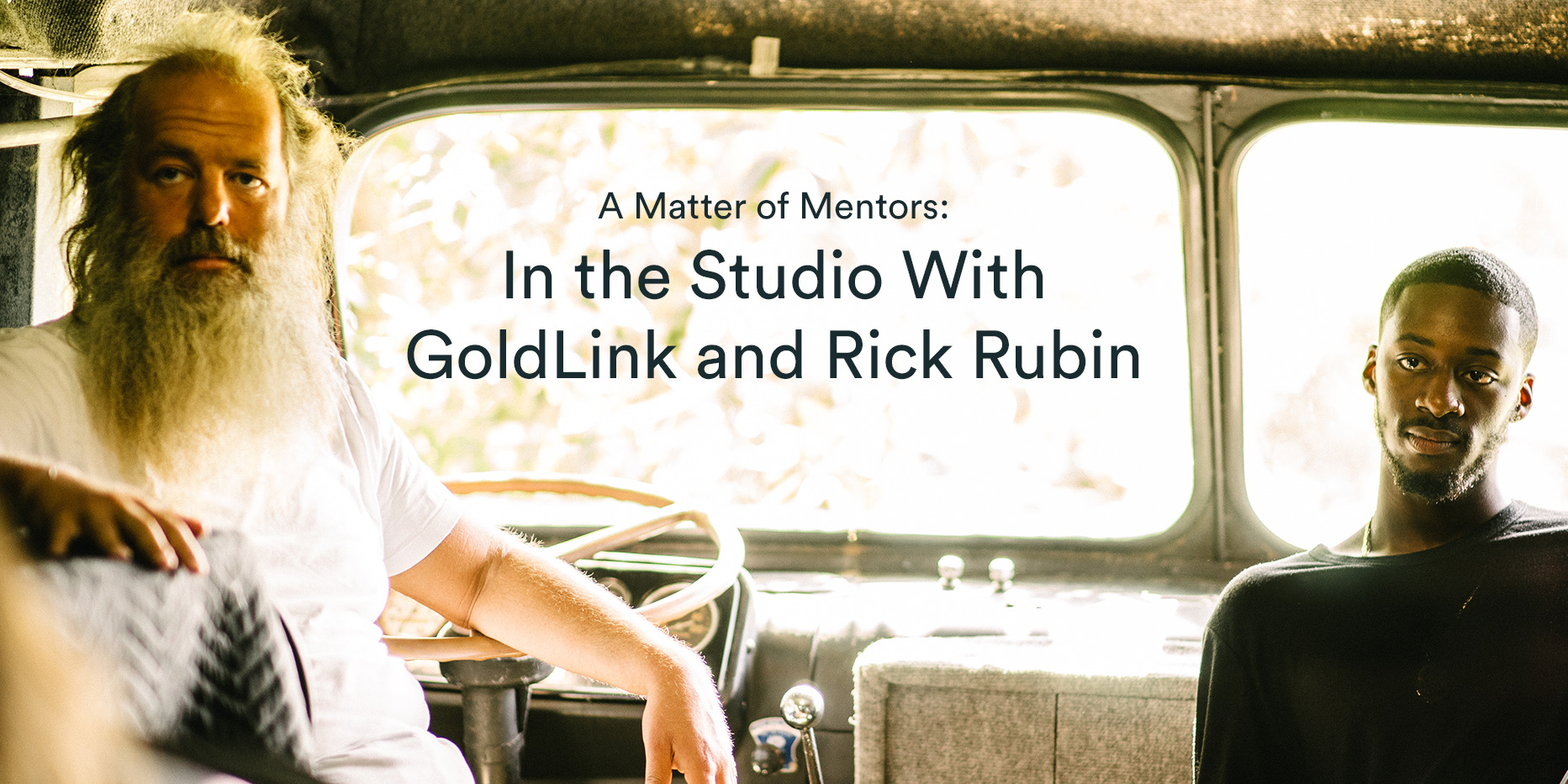

It’s late September and Rubin and GoldLink are sitting inside of a bus that Bob Dylan used to live in; the vehicle has since been converted into a studio and is now parked in the backyard of Shangri La, Rubin’s Malibu studios. “We probably mixed half of Yeezus in this room,” Rubin says, introducing the space. “Good history." It’s a history that Rubin seems to think GoldLink has a place in, and a history that, for the moment, the 22-year-old MC can’t avoid: Tonight, Rubin is taking GoldLink and his crew to see West play his 808s & Heartbreak show at the Hollywood Bowl. And while the art for GoldLink’s breakout 2014 mixtape, The God Complex, referenced Kanye’s famed Margiela masks, the new album’s cover takes cues from Yeezus’ minimalism and idolatry with its line-drawing of head wearing a crown of thorns smeared by a red streak that might be lipstick, or blood.

The shift to more intimate imagery suits the mood of And After That, We Didn’t Talk, a breakup album about a relationship GoldLink had when he was just 16 and better known by his real name, D'Anthony Carlos. Suitably, there’s more soulful crooning on this record, but GoldLink’s core blend of uptempo raps with his main producer Louie Lastic’s dance beats persists. “Spectrum”, the first single, is most evocative of GoldLink’s self-described “future bounce” sound: A Missy Elliot sample floats over spacey beats as the rapper’s lightspeed rhymes weave through recordings of his ex-girlfriend speaking in Tagalog. It’s a disorienting mix but also energizing and enticing—like you’re embarking on a Virgin Galactic trip to an interstellar club.

GoldLink: "Spectrum" (via SoundCloud)

Sitting in the driver’s seat of the bus, Rubin listens intensely, his peaceful smile lending him the air of a zenned out Santa Claus. “It doesn’t sound like anything you’ve ever done before,” he declares after listening to “Polarized”, a track featuring winey horns that would blend in at a West African jazz club. Rubin fully engages with each track: eyes closed, his tattered espadrilles kicked off to the side, barefeet tapping, tanned knees bouncing.

He’s fully feeling himself, but he still manages to couch criticism in between compliments. He calls one song lyrically “throwaway.” Another is merely “ordinary.” “I know exactly what you mean,” GoldLink admits, talking about the relatively pedestrian track. “It was mainly made—not intentionally—for the basic listeners.” GoldLink defers to Rubin’s notes with a politeness reserved for elders and legends, and Rubin is, at times, outright fatherly in return. After hearing “H-H Interlude”, a politically raw but sweetly delivered track that concludes with the sound of gunshots and children laughing, Rubin suggests for GoldLink to read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ recent bestseller about race in America, Between the World and Me. “You’ll like it,” he says.

GoldLink yells to Louie to write the name of the book down, then sits back in his chair. “Look at me being black and conscious,” he says, before cracking up. This is a rapper who delivers his messages with a mix of seriousness and play, of thoughtfulness and brashness, sometimes at the same time. When I ask him which artists from his generation might be considered timeless, he responds with one word: “me.” Right now, he’s just psyched on the possibility that he’ll end up sitting next to the Kardashians at the Kanye show. “It’s possible,” he says. “We’re in the family section.”

After the album ends, GoldLink steps out of the bus and eats tacos with his crew as they overlook the Pacific Ocean. Then, while driving along the coast back to L.A., he takes a moment to debrief about his session with the Yoda of music and why he’s sworn to the truth in his raps.

“I feel like 99% of niggas lie in they raps; I don’t.”

—GoldLink

Pitchfork: Was there anything Rick said that was surprising or different from what you expected?

GoldLink: The fact that he damn near loved it was surprising. Other than that, he didn’t say anything that I didn’t expect. I know what he likes, but I kind of play him shit that he would hate on purpose, just to see what he thinks. He was like, “I kind of hate R&B,” so I was like, “Here’s this R&B track! What do you think?” And he’d be like, “It’s good!”

GoldLink: "Movin' On" [ft. Louie Lastic] (via SoundCloud)

Pitchfork: How has that relationship evolved throughout this project?

G: When I first met him, I was kind of quiet, but now we’re close. We can talk really freely. I hit him up when I need him, and he’s always responsive. He says stuff for free. He’s always looking out for me, you know?

Pitchfork: You told Rick you went through “800 intros” while putting this album together, why is the first track so important to get right?

G: Whatever world you create, that’s what people are going to be stuck in. That’s why I’m really keen on the intro and the tracklist. I don’t want the album to feel like one consistent vibe, but rather that you’re going through a lot of emotions at the same time; I was balancing a lot mentally when I did this album, keeping a lot of things in mind. So if you don’t like dance-y stuff, then you’ll like sing-y stuff; if you hate my fucking voice when I sing, then you’ll like the rap shit; if you hate all that stuff and wanna be basic, then you’ll like another record. So I’m really trying to do that and stay me and then, I don’t know, grow as an artist.

I also didn’t want to curse as much. Travelling changed that. The more people I encountered, the more I realized what an impact my music has: I can’t say I wanna beat niggas ass all the time, I can’t just say “bitch” for the sake of filling a word in.

Pitchfork: What made you realize that that was important? A lot of performers still curse a lot when they’re speaking to a bigger audience.

G: It’s more about the actual human interactions. Somebody would meet me and be like, “You helped me with the death of my father.” And there was another kid at a Dallas show that couldn’t get in, so he stood outside for at least four hours to give me a portrait that he created. Those are the things that make me feel like I have to do better for them. And as I’m getting older, things are changing, my life’s changing. Eventually, I want to become a father. By the time I’m 30, I’m going to look back, and then what? So I thought about all those angles and started to be more honest.

"Think about it: You’re not just gonna shoot somebody or sell drugs and then everything’s gonna be OK. It’s not like that."

—GoldLink

Pitchfork: In one new song, you say that hip-hop will die if people continue to lie in their raps.

G: I feel like 99% of niggas lie in they raps; I don’t. And the thing is, if niggas gonna lie and say they’re gonna shoot somebody, they should at least tell the facts of the story. Because you likely gonna get caught. Think about it: You’re not just gonna shoot somebody or sell drugs and then everything’s gonna be OK. It’s not like that.

Rap songs had me start selling drugs, and that shit was not what I thought it was. So if you gonna tell it, just tell the whole truth. There are more negatives than positives, so if people stop lying in their rhymes, they would stop misleading a generation the wrong way. And that pretty much has to do with pure personal experiences about what I seen growing up in my neighborhood, about how my dad’s people sold crack, cocaine. I grew up when all of them got out of jail, on the block with them, and I saw how all their kids grew up just like them and went to jail. One of my friends is serving 33 years. Armed robbery. Those are the things you should rap about. I don’t think you should glorify it at all. I don’t really glorify it. I just talk about it. There’s nothing special about that life.