Review: Samuel Barber: Complete Songs

- At June 26, 2024

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

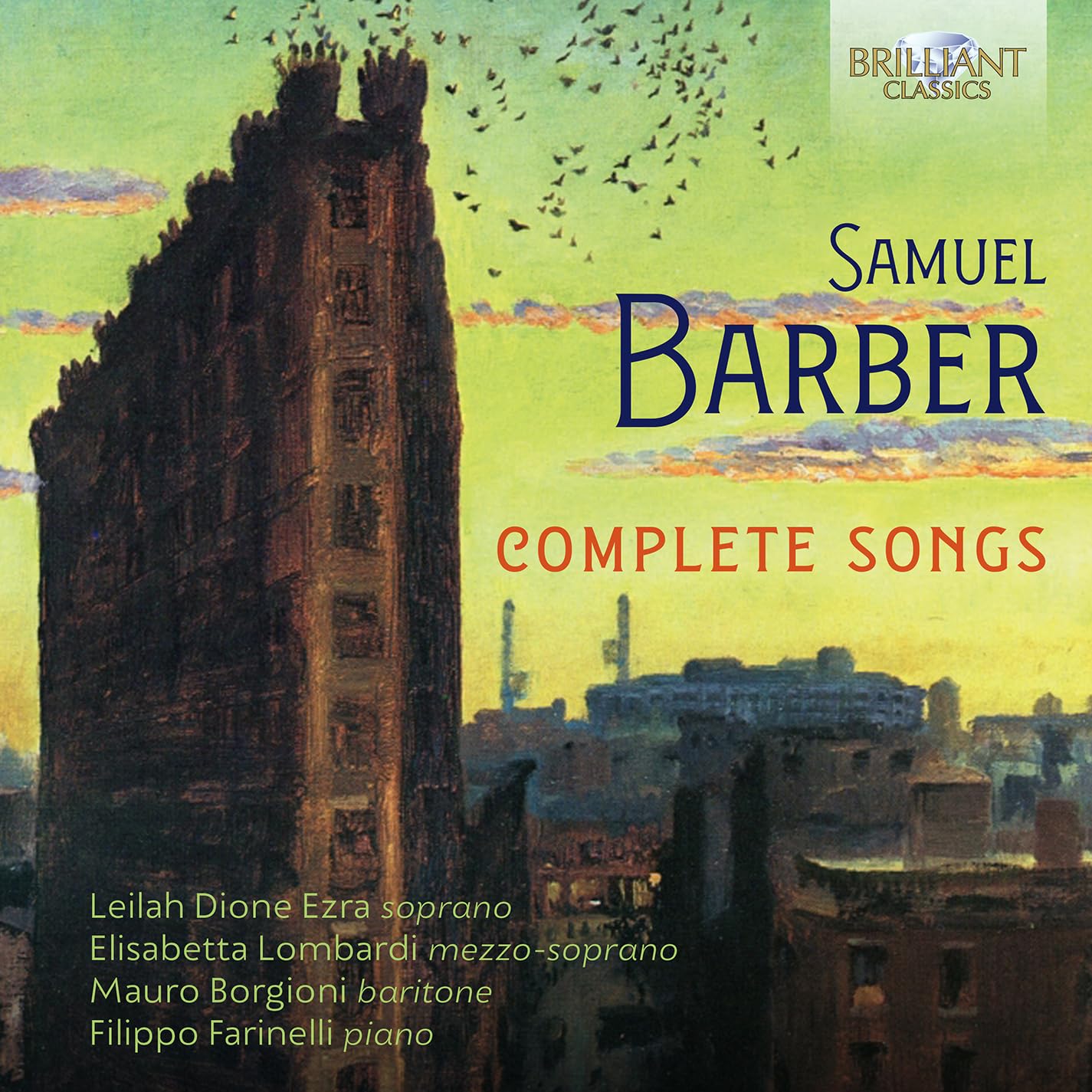

Samuel Barber: Complete Songs

Brilliant Classics, 2023

Filippo Farinelli, et al

Review by Allen Ruch

26 June 2024

Since 1994, fans of Samuel Barber had only the Deutsche Grammophon Secrets of the Old set to represent Barber’s complete songs. Featuring soprano Cheryl Studer, baritone Thomas Hampson, and John Browning—the pianist who premiered Barber’s Pulitzer-Prize winning Piano Concerto—this collection has long been a “must own” album. Nevertheless, thirty years of the same interpretations can’t help become overfamiliar. Then something amazing happened—two excellent sets arrived in as many years.

Like the 2022 Resonus CD featuring Dylan Perez and an all-star cast of British singers, this new set by Brilliant Classics includes all the pieces from the Browning collection, plus many of Barber’s early and lesser-known works. The 65 songs are divided among three singers: Italian baritone Mauro Borgioni, American-Israeli soprano Leilah Dione Ezra, and Italian mezzo Elisabetta Lombardi. All three bring a fine sense of operatic drama to the songs—particularly Borgioni, who approaches Barber not unlike Verdi or Puccini. But the real star here is pianist Filippo Farinelli. Known for his interpretations of thornier composers such as Berg, Dallapiccola, and Hindemith, Farinelli deftly embraces the sophistication of Barber’s writing, but never loses sight of the lyricism that charged his recordings of Debussy and Ravel. Farinelli confidently locates this American composer in the storied tradition of European art music with Berg and Stravinsky, at home with Barber’s many contradictions and fusions of style.

This being a James Joyce site, this review will focus on the set’s Joyce-related songs. All six songs from Chamber Music are sung by Mauro Borgioni, whose dark baritone enfolds Farinelli’s flashing piano like a warm, Italian night. These are dramatic readings that wouldn’t seem out of place at La Scala—“I hear an army” unfolds like thunder rumbling across a tortured landscape, and Borgioni’s “why have you left me alone?” raises goosebumps. (He’s also fond of rolling his r’s and cutting off stanzas with a theatrical slash—I would love to see him as Baron Scarpia!) While some might prefer a less ornate reading, Borgioni’s idiosyncratic pronunciation is a more pressing concern, and it’s clear English is not his native language. This is the most evident on “In the dark pinewood,” where words like “shadows,” “kiss,” “enaisled,” and “tumult” strike the ear with discernible accents. Still, it’s hard to hold that against him when he draws out the conclusion of “Stings in the earth and air” with such graceful delicacy.

Farinelli matches Borgioni’s theatricality with dramatic displays of his own, slowly building up and unwinding the tension in “Rain has fallen,” and drawing out the chords in “Sleep now” like the drifting thoughts and sudden anxieties of an unquiet night. And never have the galloping horses of “I hear an army” felt more ominous—just terrific playing, even on the simplistic ascending/descending riffs of “Pinewood.”

Of all the Joycean pieces, Nuvoletta is the most colorful, flecked with Wakean language, flickering rhythms, and soaring melisma. Farinelli takes the song at a slower tempo than usual—a full two minutes longer than Barber’s own performance with Leontyne Price, and one minute longer than most contemporary recordings. It’s a decision that pays off handsomely, giving him time to explore its many moods and complexities, allowing this “Little Cloud Girl” to make up “all her myriads of drifting minds in one.” The soprano Leilah Dione Ezra sings Nuvoletta with a consistent, honeyed tone that illuminates the song’s artful musicality, and it’s rarely sounded so beautiful—her “Tristus Tristior Tristissimus” is sublime. However, this commitment to beauty comes at the expense of the nimble wordplay of the lyrics. There’s a playful strangeness to this song that benefits from a more Protean approach, one that doesn’t gloss everything over with unrelenting “prettiness.”

The saddest of all Barber’s Joyce songs is “Solitary Hotel,” the fourth song in Despite & Still, op. 41. The five-song suite was written during a period of depression following the failure of his opera Antony and Cleopatra. Adapted from the “Ithaca” catechism in Ulysses, “Solitary Hotel” begins with Stephen’s playful idea for an intriguing setting: a solitary, alpine hotel where a pensive woman flirts with a mysterious letter. The fanciful scenario comes crashing down when mention of Queen’s Hotel reminds Bloom of his father’s suicide. As usual, Farinelli’s playing is masterful, investing the song with hesitation and fragility. Avoiding the grandeur that overburdened the whimsy of Nuvoletta, Ezra unfolds the narrative with heartbreaking clarity.

A macabre song about a man who finds himself buried alive, “Now have I fed up and eaten up the rose” is Joyce’s translation of a poem by Gottfried Keller, a poem he first heard in a musical setting by Othmar Schoeck. The titular rose refers to the doomed man’s last supper—his own funeral corsage! A metaphor for artistic exile and creative decay, “Rose” is one of the last songs Barber wrote. Mauro Borgioni’s reading is thick and lugubrious—though not so resigned to death he forgets to roll his r’s and include the odd dramatic flourish! Nevertheless, his final “Amen” is perfect, touched with an irony lost on many interpreters.

I should quickly mention that the mezzo Elisabetta Lombardi is reserved for Barber’s French songs—Mélodies passagères, “La Nuit,” and “Au claire de la Lune.” On the darker side of the mezzo spectrum, she’s well suited for these pieces, and sings with the same melodic clarity that enriched Farinelli’s previous collections of Debussy and Berg. It would have been interesting to hear her sing “Now I have fed and eaten up the rose”; but for now, Jess Dandy’s contralto version for Resonus stands as the definitive “feminine” reading of Barber’s ironic dirge.

And finally, the album boasts impeccable sound production. There’s an immediacy to these recordings completely lacking in the DG set, and not quite achieved by Resonus—the voices fill the room, but never overwhelm Farinelli’s expressive accompaniment.

While some listeners may prefer the multiple voices and stylistic approaches of the Resonus set, those interested in Barber’s writing for the piano will find no better testimony to his unique genius than Farinelli’s latest collection for Brilliant Classics. The singing has its quirks—it’s a decidedly Italian reading of Barber, very operatic at times—but Farinelli’s piano is a revelation. Critics have often argued how to classify Samuel Barber. Is he a late Romantic? A tentative modernist? Farinelli lets Barber’s music speak for itself, like Walt Whitman’s wandering astronomy student who “look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.”

Additional Information

Joyce Music: Samuel Barber

The Brazen Head features several pages on Samuel Barber and his Joyce-related compositions.

Samuel Barber: Complete Songs

The entire album is available for listening on YouTube.

Brilliant Classics Release: Samuel Barber: Complete Songs

The Brilliant Classics page features sound samples and recording notes.

Samuel Barber: Complete Songs [CD]

You can purchase the compact disc at Amazon.com.

Samuel Barber: Complete Songs [Digital]

Audiophiles may download the 24-bit FLACS from Presto Music.

Author: Allen Ruch

Last Modified: 26 June 2024

Joyce Barber Page: Samuel Barber

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com