Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) says that “no firm decisions” have been taken about selling rare books from its collection after more than 600 of its fellows and members wrote an open letter opposing such a move.

The college has been working with auction house Bonhams to understand the practicalities around making a sale, which it says could raise £6m and help it avoid making redundancies. But the plans have met fierce opposition from within the college and the museum and library sector.

The Museums Association’s (MA) Code of Ethics, which forms part of Arts Council England’s (ACE) Accreditation Standard for museums, says collections “should not normally be regarded as financially negotiable assets”.

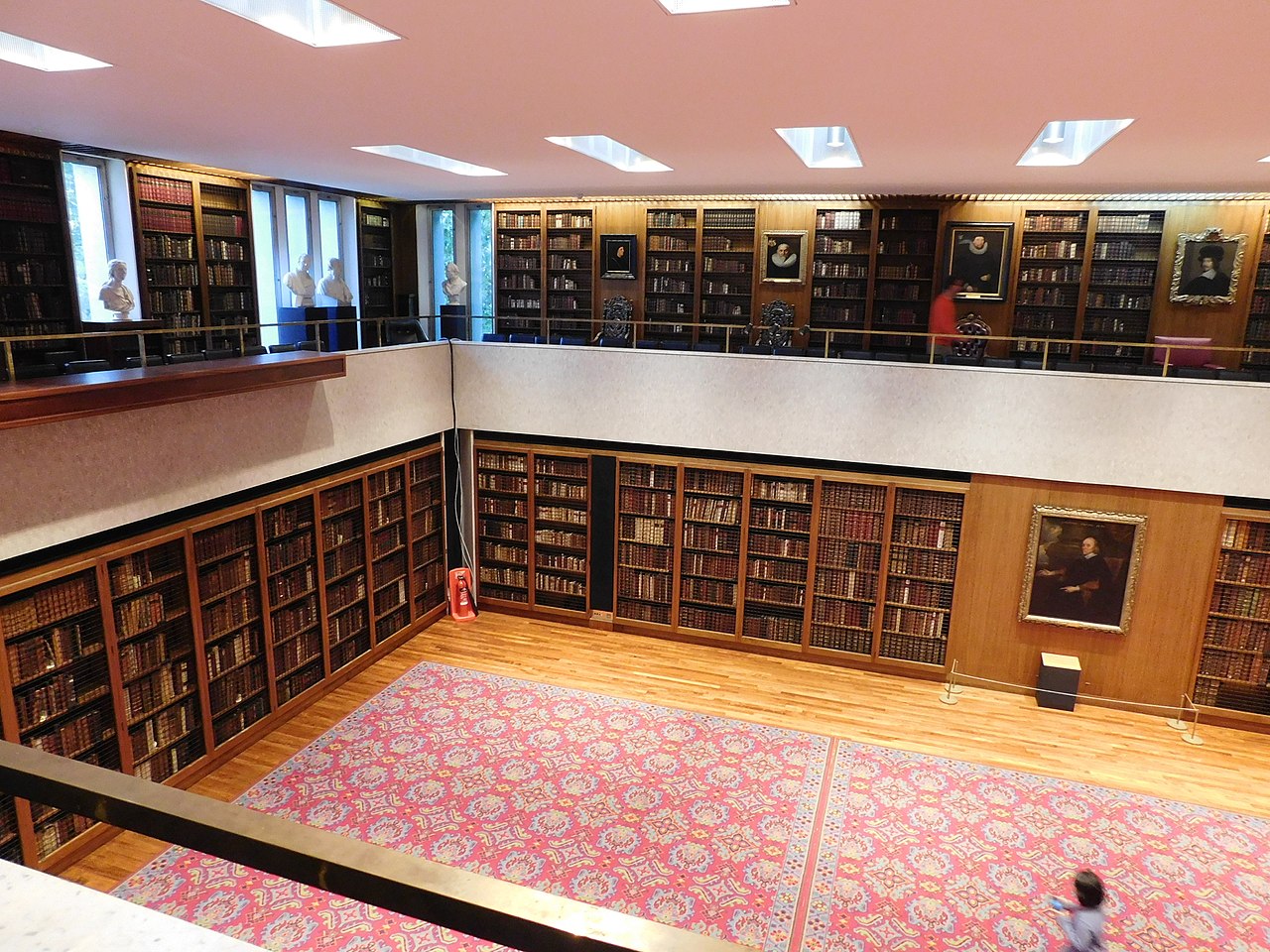

The RCP has a significant library, archive and museum collection including donations from medical pioneers such as William Harvey. The college says there are no proposals to sell any specific books yet, but the Times recently reported that a sale was planned from a collection bequeathed by the Marquess of Dorchester in 1680. This includes some of the RCP’s rarest books, such as an early edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, a psalter that belonged to Elizabeth I’s astronomer John Dee, and Recuyell of the Histories of Troye, the first book printed in English.

More than 600 members, fellows and honorary fellows of the college have opposed a sale in an open letter to the RCP's president Andrew Goddard and its chair of trustees David Croisdale-Appleby. They say selling important material from the collection would be a dereliction of duty, representing “a breach of trust between the public, the benefactors and the college through the irreparable damage caused by the transfer of the college’s and the nation’s cultural inheritance into private hands”.

Signatories include the former UK government chief scientific adviser Mark Walport, as well as two former RCP presidents – Carol Black and Richard Thompson.

They say “the sale of important material from the college’s unique and important collection would damage its reputation, nationally and internationally, amongst fellows, members and the wider medical profession”.

The letter also complains of a lack of transparency from the RCP’s leadership and questions the financial need for a sale when the college’s most recent accounts say it is a “going concern”.

A letter from Goddard in response confirms that a sale is under consideration, presenting this as one of several possible ways of addressing the financial difficulties created by Covid-19. Goddard says the college will lose 31% of its income (£14m) this year because of the pandemic and predicts a further loss of £9m next year.

He says that a sale has been considered by the RCP’s board of trustees for several years, and that formal steps towards one began in mid-2019 when funds were needed for the fitout of a new RCP office in Liverpool. The plans were put on hold when a £6.75m bank loan was secured, before being dusted down amid the current crisis.

Goddard says the college ran a deficit of £8.8m between 2016 and 2019, but adds that this was planned, and offset by investment gains. He says that a £3.2m drop in the organisation’s reserves from 2014 to 2019 came from addressing a pre-existing pension scheme deficit.

The letter stresses that “we have not agreed to sell any particular book” and says members will be consulted about the available choices in the next few weeks.

Goddard says that any assets sold would be “non-medical”. But the question of what this means is raised in the open letter, whose authors say the wide-ranging intellectual interests of medieval and early modern physicians makes such boundaries “arbitrary”.

Goddard’s letter says “the definition of ‘non-medical’ is one of individual perspective” and adds that the college will work with its elected council of fellows to reach a final decision on this.

The RCP’s website says its library collection “reflects the interests of past physicians and the broad education they were expected to have”, including rare books on law, architecture, travel and cookery as well as science and medicine.

Goddard’s letter says the college recognises the need to “follow an ethical approach to de-accession if we go down this route”.

It says that during initial discussions with experts in 2019, “the risk of a temporary loss of museum Accreditation status was made clear early on and was felt by our advisers to be preventable if we decided to go ahead with the sale”.

“We are still working with our library and museum team to understand how deaccession can best be done to minimise the risk to our museum status,” wrote Goddard.

The letter says the RCP recently began working with Bonhams to ensure it understands its book collection’s “provenance, value and what would have the least impact on our collection whilst allowing the RCP to avoid significant redundancies”.

The MA Code of Ethics says museums should “refuse to undertake disposal principally for financial reasons, except where it will significantly improve the long-term public benefit derived from the remaining collection”.

It says objects should only be sold in this way as a last resort, when other sources of funding have been thoroughly explored, and “not to generate short-term revenue”.

In 2014, ACE stripped Northampton Museums Service of its Accreditation after it sold an ancient Egyptian statue at auction for £15.8m. In September it was reported that some academicians at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) had called for the sale of a Michelangelo sculpture to prevent job cuts, but the RA said it had “no intention” of doing this.

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

You must be signed in to post a comment.

It sounds like the desire to get money from selling things is preceding a decision about what the money would be used for. The same thing happened in Northampton and it always leads to muddled thinking. Financially motivated disposal can only work when: 1) the organisation knows what the money would be used for and it isn’t likely to be able to get the money from anywhere else; and 2) the organisation has a clear view of the long-term purpose of its collection (that purpose can change over time but it shouldn’t change very often). Without that there’s no chance of meeting the detailed requirements of museum ethics. If Philips isn’t telling them that, then they need different advisors if they are to have any chance of behaving ethically.

Sorry, Bonhams rather than Philips

Is it clear that this is financially motivated disposal just for the sake of it or are they posturing that its function is to save jobs like the Tate? In which case, would it then be justified?

The question of what can be justified, and in what circumstances and under what protocols, is key, surely, given that survival-threatening financial pressures are now going to be with UK institutions for a generation or more. Good though it must always be to challenge the rationale for such fire-fighting disposals of assets, they will very probably become inevitable if many public collections are to remain adequately cared-for, let alone open at all.

This has already happened with other ancient (and indeed local) libraries and is deplorable.

Unfortunately, as in other areas, the MA has downgraded and weakened its policies on disposals, leading to a burgeoning enthusiasm for it. The excuses are legion – not suited to our policies, raising funds for projects, deteriorating, etc. The dangers are that individual whims lead to the loss of material of unrecognized value, because the decision leaders and makers are ignorant. We have seen it with libraries for some decades, with collections broken up to avoid ‘duplication’.

In my home county the disposal of public library books, many dating back centuries and often given for the benefit of the museum service) took place secretly and led to legal action – too late. At least one other county had the same happen. I recall visiting a book dealer who had a room full (and I mean full) of books sold off from his county library. He had learned of secret sales and managed to get the business opened up. The idea that such sales of rare books was itself questionable never arose. Rugby School library is just about to have an auction, with the dispersal into mainly private (ad probably foreign) hands of hundreds of rare books. Is the money raised going to assuage the loss to China, Japan, America, or wherever of such treasures?

We are now seeing parochialism – actively fostered by the MA’s collections policies ideas, doing the same. County towns are seeing their collections only of value insofar as the modern (and temporary) Districts or Boroughs are concerned. The historic boundaries, or the ability to widen the horizons of the people by showing material from beyond purely local horizons, are destroyed. Travelling exhibitions are no substitute for ‘our mummy’.

The disintegration and dispersal of collections threatens the willingness of people to donate. I and my wife have already decided not to make any donations to a museum, and I was a Director of the MA and a member of the Board of Studies and the Board of Examiners in the days when collections were still at the heart of what we do. Today the news from the MA is almost exclusively about how museums can be used for political purposes of one kind or another.

When the Museums Association again gets its act together and genuinely values our unique selling point (things) over philosophies and political posturing, we may as a profession actually be able to criticize with some degree of integrity.

If members have not seen the new book from Peter Brears, “Carry on Curating”, it holds many truths which many of the present generation will find uncomfortable and perhaps even unpalatable. It also pulls no punches about our own failings in the past.

It is time that we remembered curatorship is our raison d’être and ensured its survival. Sadly, it may already be too late because for many years professional staff have seen themselves (and been encouraged to do so) as managers rather than researchers, as shopkeepers rather than interpreters, and as political voices rather than unbiassed presenters.