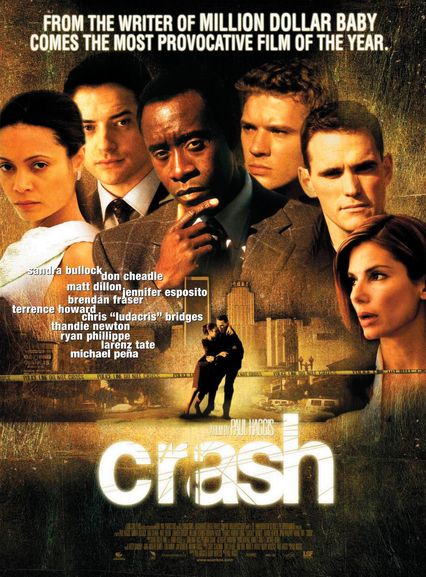

In 2006, Crash, a contemporary film about racism made on a $6 million budget, shocked Hollywood, and its own creators, when it won Best Picture at the Oscars — the result of a prescient producing team, a famously canny awards campaign, and an unanticipated flood of support for this apparent underdog to the heavy favorite, Brokeback Mountain. The story of how Crash upended the industry — and changed how Oscar campaigns are waged — is best told by co-writer–director Paul Haggis and the industry players who experienced the film’s journey from a cast-aside TV concept to perhaps the most surprising Best Picture winner of all time.

PAUL HAGGIS, director, co-writer: In August 2001, I was fired from my own television show, CBS’s Family Law. It was the second time this had happened in my career, the first being when I was fired from The Facts of Life. I had been grateful to work in TV for so long but had always been chasing a career as a feature writer-director and had completely failed. I had optioned the rights to F.X. Toole’s short story Million Dollar Baby, written it on spec, and sent it around starting in 2000. I wanted to direct it, but it was very quickly made clear to me that no one wanted me to direct. [Laughs.] In late 2001, the thought of going back to television was just eating my soul. My then-wife, Deborah, said to me, “You know that TV-show idea you had? You should write it as a movie. You’ll win an Oscar.” I went, “Oh, okay.” [Laughs.] She reminds me of this all the time. It was an outline for a concept I’d written about how prevalent feelings of racism were in America; the decisions we make about people based on their look, race, and ethnicity. The stereotypes we pretend that we reject are ingrained in our DNA. I’d taken the concept around, but nobody wanted it. So I pulled out the 35-page outline again and remembered why I loved it so much. I called my friend Bobby Moresco and said, “I think this is a movie.”

BOBBY MORESCO, co-writer: I liked it, but there was just too much there to be a movie. How could we possibly turn all these stories into one piece?

HAGGIS: I’d originally done two years’ worth of research to prepare the pitch. I’d held town-hall-style interview meetings in my living room with people. I wanted to understand the experiences of living in different areas of Los Angeles after getting used to only the whiter parts of town. L.A. is so segregated, but no one ever talks about it. I told Bobby, “In the first 30 minutes, we’re going reinforce every stereotype. We’re going to tell the audience, ‘I know you’re a big liberal, but you can laugh because we all know Hispanics park their cars on their lawns and Asians can’t drive. Relax. No one’s gonna know you’re laughing.’” And then we’re going to turn it around so you leave the theater questioning everything. I sat at the keyboard and Bobby read the pages and threw out ideas. Then we’d rewrite. It was very quick. And then we got turned down by every financier in America and Canada.

CATHY SCHULMAN, producer: I had a company at the time called Bullseye Entertainment, and financier Bob Yari had essentially bought half the company. He sent me a pile of scripts and asked, “Why don’t you see if there’s anything there?” On a rare rainy Saturday afternoon in L.A., I’m curled up on the couch alone in the house. I’m really engrossed reading Crash, and then there’s this knocking on my window and it’s my mailman. I look away because he normally just puts the mail in the mailbox. And he knocks even harder. And I shoo him away. I’m in the middle of the script! And then he gives me this really sour look. I throw the script down kind of in a huff and run to the front door, and I realize there was a big package he was trying to hand to me so it didn’t get wet. So he left it out in the rain. And I wanted to call him to come back and say thanks, but I didn’t know his name. He was African-American and had been coming to my house for years. And I go, “Sir, sir!,” and he comes back and I try to apologize. It’s very uncomfortable. Then I go back to reading and I realize I’m literally the character that ends up as Sandra Bullock’s character. I’m thinking, I’m a bitch. I’m a racist. I felt guilty. He was just trying to be nice and I was a bitch! I felt really callous in that moment; I felt the same kind of separation from my fellow human being that was in the script. Paul and Bobby really wanted us to make the movie in-house, but we didn’t have the money so marched all around town. And everywhere I went, people were like “Oh, for God’s sake, Cathy, a movie about racism?” It was really hard to raise the money.

HAGGIS: Then Bob Yari says, “Okay, we’ll give you around $7.5 million if you get X number of movie stars.” That all started with casting Don Cheadle, who also signed on as a producer. But it was made very clear to me that his name meant nothing, which I took to mean had a lot to do with the fact that he was black. We’re making a movie about this exact same thing and you’re telling me you can’t make it because he’s black? I realized I really had to make this movie.

MICHAEL PEÑA, actor (Daniel): I think Crash may have seemed like an easier sell to people if it were written by, say, John Singleton. Then it’d be a “way of life” story. But because a white Canadian guy was doing it, people reacted differently to it. They were nervous. I’d grown up in a low-income area in Chicago. I think 80 to 90 percent of cops are good people, but the kind of stuff we see Matt Dillon’s character do in the movie did and still does happen where I come from.

CHRIS “LUDACRIS” BRIDGES, actor (Anthony): When I read the script, I knew 100 percent it was something I wanted to be a part of. I had to audition at Paul’s house in front of him and Don. I was extremely nervous.

HAGGIS: Thandie Newton was the second actor I sent it to, and she said yes. Others said, “Yeah, I’m not gonna do this,” and ran away. I also lost a lot of actors because it kept getting pushed. John Cusack wanted to play the Matt Dillon role, Heath Ledger was going play the Ryan Phillippe role; Forest Whitaker was actually locked in to play Terrence Howard’s role but dropped out. And Brendan Fraser was the last one cast, as the district attorney. He essentially green-lit the movie.

YARI: When Heath left the movie, we dropped in foreign value a little bit, which brought the budget down to around $6.5 million. Many actors wouldn’t come on the film at all because they said, “It’s a first-time director.” But I stuck with Paul.

BRENDAN FRASER, actor (“Rick Cabot”): I was in my mid-30s at the time. I asked Paul, “Are you sure that I’m the man to play the district attorney of Los Angeles?” He said, “You’re fine. I did my research. But I’ll be straight: I need you onboard because it’s going to complete the bonding with the picture.” I told him, “I’m worried I might come off as a little too Canadian.” See, he and I share that heritage. He said, “Oh, don’t worry, I can be a real asshole.” [Laughs.]

HAGGIS: We decided to film in December 2003 — our Christmas card to Los Angeles. Race and intolerance, just in time for the holidays! [Laughs.] We shot in the winter because it actually did snow the first year I was in L.A. I remember thinking, If it could snow here, anything is possible.

PEÑA: I’d just finished my third episode of NYPD Blue playing a different gangster with a different name. Crash was my first meaningful real part after years of having a chip on my shoulder and thinking, This Latino thing almost works against me.

HAGGIS: We had enough money to shoot 32 days. The actors all agreed work for scale [which in 2003 for actors with smaller roles was around $6,000 a week; for featured performers, about $57,000 in total]. I told them, “You only have to be here for a week.” We doubled up on locations as well. For example, Matt Dillon’s character’s house was also Thandie Newton and Terrence Howard’s characters’ house. We made decisions like that over and over. It was the only way to make the schedule.

TERRENCE HOWARD, actor (Cameron Thayer): Don and [co-star] Larenz Tate had recommended me for the part of Cameron after Forest dropped out. They were already a few weeks into production when I came onboard. My initial thought was: This was a monster of an undertaking.

MORESCO: The most any of the actors would ask us was, “Is it working? Can I go this far?” I constantly pushed them for deeper, stronger, and more real. There wasn’t anyone who didn’t run with it. We went home every night pretty confident we got what we needed for the day. Paul may have felt differently at times [laughs]. But I think we felt like we were shooting the movie we wanted to shoot, amidst all the problems.

HOWARD: The scene where my wife [Thandie Newton] is molested by the cop was difficult. But trickier for me was when Tony Danza’s character tells me to make the character in our TV show “more black.” I remember Paul telling me how when he worked for a network, there were execs who told black jokes and his black colleagues had to just laugh along. He wondered what their lives were like and what it felt like to be ethnically neutered.

HAGGIS: To be honest, I really didn’t know what I was doing most of the time. Bobby is always so positive and sweet. I’m the total opposite. I was like, “We’re never going make this.” I was brought to tears one day because everyone got sick with the flu and nothing was working.

SCHULMAN: Did Paul mention that he literally had a heart attack on the last day of shooting the final scene in Chinatown? I’d never seen somebody turn a pale-greenish-whitish color, and he was complaining about his arm. And sure enough, he fell down on the ground, and we were lucky that we already had a helicopter on-set, because it brought him to Cedars. He had surgery, and five seconds later he was asking me, “How many people were in the intersection in the final scene? We needed a lot of people!” I told him we had plenty. He went crazy. “We’re going to have to reshoot the whole movie!” He had no idea what he was talking about. I’m like, “You’re high on morphine!

HAGGIS: After my surgery, the doctor insisted I couldn’t go back to work for four months. I asked him how much stress he thought I would be experiencing sitting at home while another director was finishing my film. So we were back shooting a week and a half after my procedure with the understanding that I had to sit in my director’s chair at all times, and that my blood pressure had to be monitored every fifteen minutes. However, Don Cheadle had to leave to shoot Hotel Rwanda, so we couldn’t complete the film until he finished that. He came back two months later, we shot for a week, which included that extra insurance day we’d gotten when everyone got sick. And thank God we had extra time, because Bobby had time to write a new scene and add the character of Flanagan, the City Hall fixer played by William Fichtner.

SCHULMAN: Brendan had to leave to go do a Broadway play, and he couldn’t get out of the contract, but we hadn’t finished shooting him yet!

HAGGIS: We had shot 98 percent of Brendan’s scenes and couldn’t afford to get back into City Hall to shoot the end of one scene we had planned, so we had to rethink it, and we came up with the Flanagan character as a fix.

FRASER: By then we had nicknamed the movie Trainwreck. [Laughs.] We were selfish actors, everyone was griping. “Where is my paycheck?” I’ve learned since in my grizzled old age that stuff like this happens on every production.

PEÑA: I definitely made less than 10,000 bucks. But I was so stoked just to have a role. Like, Whoa, this is my dream.

YARI: The movie was edited in our building, and I was thrilled with the first cut. Usually we have a lot of opinions and test the film, and those results may cause us to ask for certain changes. But this time, the first cut was phenomenal.

HAGGIS: I saw it on the big screen for the first time at the Toronto International Film Festival in September of 2004. It was horrifying. I wanted to escape. The cast was there. I was sitting with Deborah. After it was over, I saw people were gasping and crying, and I’m going, Who are these idiots? All I saw were the mistakes. The spotlight hits me, and there is a thunderous ovation that goes on and on. I think, Okay, it’s Toronto. They’re polite. I dismissed all these people who wanted to shake my hand and tried to get out of there as quickly as possible.

SCHULMAN: My friends still say it’s the biggest standing ovation they’d ever seen at the festival. I was like, Oh my God! We’re going sell this movie! By that point, everybody involved was broke except for the actors. We had to make money.

TOM ORTENBERG, CEO, Open Road Films: I was the president of theatrical films for Lionsgate at the time. All of us acquisition folks sit in clusters near our competitors. After the movie ends, all of us on the Lionsgate team look at each other like, That was terrific. Our competitors were totally dismissive and were talking about where they were going to get dinner. We were giddy about what we had just seen.

SCHULMAN: Back then, a movie could sell within few hours of the premiere. But two hours later, it was still tumbleweeds. [Fox Networks Chairman and CEO] Peter Rice, one of my best friends, was running Fox Searchlight at the time and had invited me to their party — we couldn’t have our own because we were too broke — and I was a total mope. I said to him, “You haven’t told me what you think of the movie.” He said, “I love you so much, Cathy, but I have to say, I don’t think it will sell.” It was a gut punch. Then another distributor who shall remain nameless said, “It’s too much of a melodrama. It’s too predictable. It’s not realistic enough.” But we weren’t trying to be realistic. It’s a fable! My heart sank.

JON FELTHEIMER, CEO, Lionsgate: I’d had a deal with Paul at Sony, and he sent me the script for Crash fairly early on, when it was financed but had no distributor. During the festival, I got a call from everybody saying, “We saw it and love it.” And I said, “Well, get it!” It wasn’t a crazy expensive buy — $3 million — but we were aggressive about it.

ORTENBERG: We closed the acquisition the day after the premiere. I told the filmmakers right away that we saw Crash as a commercial picture and an awards contender. This was September of 2004, so they asked if we could do an end-of-year release for that season. I said, “It’s a terrific movie, but it’s not an obvious awards contender. It’s a word-of-mouth-movie. There’s a lot of work to be done.” So we decided to release it the following spring. Movies like The Silence of the Lambs, Gladiator, and Braveheart had all come out in the first half of the year and done just fine at the Oscars.

HAGGIS: I told Tom, “You’re out of your mind.” Historically, the Academy was more comfortable with films that deal with race in ways that were history-based, like, “We used to be like this, we take it very seriously, and we’re very sorry.” Race and intolerance were simply not popular subjects at the Oscars.

FELTHEIMER: Paul and the producers thought we should “platform” the movie — open in New York and L.A. on maybe eight screens and then expand over a few weeks. But we felt Crashcould work as a wide release, and it did: We opened on May 6, 2005, in 1,864 theaters. It earned $9 million over opening weekend and ended up doing a total of $55 million domestically, with a global total of over $98 million.

SCHULMAN: One thing I will forever love Lionsgate for doing is that they agreed to test in five different markets outside of urban markets. Art house, everything. And those are expensive and very hard to do well. But they did it and the movie got excellent marks. And that’s why they decided to go wide with it.

HAGGIS: I just was thrilled that people were going to see our little movie. And thankfully it was a wide release, because we got scathingly bad reviews in The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times. If those were our only cities, they’d have killed us before we even began. Also, I remember reading something in The Hollywood Reporter that said, and I’m paraphrasing: “If this film had been made ten years ago, we would’ve called it brave or cutting-edge. But we don’t have these problems anymore.” What? I didn’t necessarily think the movie would be a critical success; but the fact that people were affected by it, and Roger Ebert and a lot of the other important critics loved it nationwide, is what saved the film.

FELTHEIMER: As Paul says, reviews out of New York and L.A. were not spectacular, so if we had platformed the movie, we would have had a very hard road after that. Unfortunately — or fortunately — this business is not an exact science.

HAGGIS: In July 2005, Jon and the Lionsgate team tell us, “We’re officially going for an Oscar campaign.” I said, “That’s great. The actors did terrific work and deserve recognition.” They said, “We’re also going for Best Picture.” I told Jon, “Please don’t. Just let this be a little picture. My friends are going to laugh at me!”

STACEY MOORADIAN, awards consultant: I was senior vice-president of publicity for Lionsgate at the time. Our early-May release gave us the ability to run a home-entertainment campaign in the fall as a push into the awards-season window.

ORTENBERG: The DVD came out in September, so we instantly had a new audience. By the time the other award contenders came out in the fall, we noticed many of them were not quite hitting the mark. Voters said they liked one film and respected another film, but what they loved more than anything else was Crash.

SCHULMAN: We’d also gotten the film to Oprah [Winfrey]. That’s when everything changed. She had the cast on her show that October and officially put her seal of approval on it.

ORTENBERG: Oprah had had what she called her “Crash moment” at the Hermès store in Paris [when, Winfrey said, a clerk mistreated her because of her race]. We’d become part of the pop-culture vernacular!

HOWARD: It was a busy time for me, because Hustle & Flow was in the Oscar race the same year. Lionsgate talked about doing a Supporting Actor push for my Crash role, too, but they thought it’d get in the way of my lead campaign for Hustle. So they decided against it — and I later ended up with a nomination for Hustle.

ORTENBERG: The day we got the Best Ensemble nomination from the Screen Actors Guild in early January was a turning point. So we decided to send Crash DVDs to everybody in the guild. Our consumer DVD was already out, so we didn’t have to really worry about piracy. It was a no-brainer. Why wouldn’t we do this? Apparently no one had done this before! The total cost to ship 100,000-plus DVDs in paper sleeves was around $225,000. At the time, a For Your Consideration [FYC] billboard on Sunset Boulevard cost about $50,000 per month, and a one-page FYC ad in Variety would be about $25,000, not to mention millions spent on local TV, radio, and newspaper ads. So $225,000 was a good investment out of our overall budget for the season, which was $5 million, which felt like a lot less than that of our competitors.

HAGGIS: The decision to send the DVDs to SAG turned out to be brilliant. There are a lot of people in SAG! I’d never believed in those big “For Your Consideration” ads anyway. It’s all so ridiculous.

MORESCO: With each awards ceremony, we started to win best original screenplay. But anytime it entered into my mind that we could win an Oscar, I pushed it out.

HAGGIS: Then, we get six Oscar nominations! It was surreal. Wow, I’m an Oscar nominee. It was Crash, Capote, Brokeback Mountain, Munich, and Good Night, and Good Luck. And we finally got one tiny little billboard, on Sunset. I was so proud.

ORTENBERG: We could tell pretty quickly it was going be Crash versus Brokeback.Then Brokeback started winning most of the critics’ awards, and, by the way, we hadn’t gotten a Best Picture nomination at the Globes.

HAGGIS: It’s true, the Globes have always hated my work. [Laughs.]

MOORADIAN: The Globes were all over the place that year — The Constant Gardenerand A History of Violence were nominated over us for Best Drama — so it was unclear how strong a precursor they’d be for the Oscars as compared to previous years

ORTENBERG: So we knew we needed a breakthrough moment. Then we won the SAG award for Best Ensemble. That’s when a lot of people said the race turned in our favor. It proved that Brokeback wasn’t invincible.

LISA TABACK, awards consultant (Spotlight, La La Land): That year, I was working on Good Night, and Good Luck. It was a film that if you loved it, you really loved it — writers and directors in particular. Crash, however, appealed to actors, who represent the biggest branch in the academy. It’s also a very West Coast film, and voters are based there more than anywhere else. The issue of “getting along” post–Rodney King had been an issue in L.A. for many years. The film talked about race, and not just in terms of black and white; a lot of different ethnic groups are represented in the film in a way they weren’t in others. And that really resonated with people.

HAGGIS: After a while, I started to feel very uncomfortable with all the attention. So I took off to Europe for three weeks to research and write In the Valley of Elah. I come back and people are telling me, “You know, Crash actually has a real shot at winning.”

SCHULMAN: The day before the Oscars, my publicist tells me, “The Vegas odds just went your way.” I was like, “Everyone’s telling me different shit.” I’d just heard the trend was going more toward Brokeback! He said, “You have to prepare a speech.”

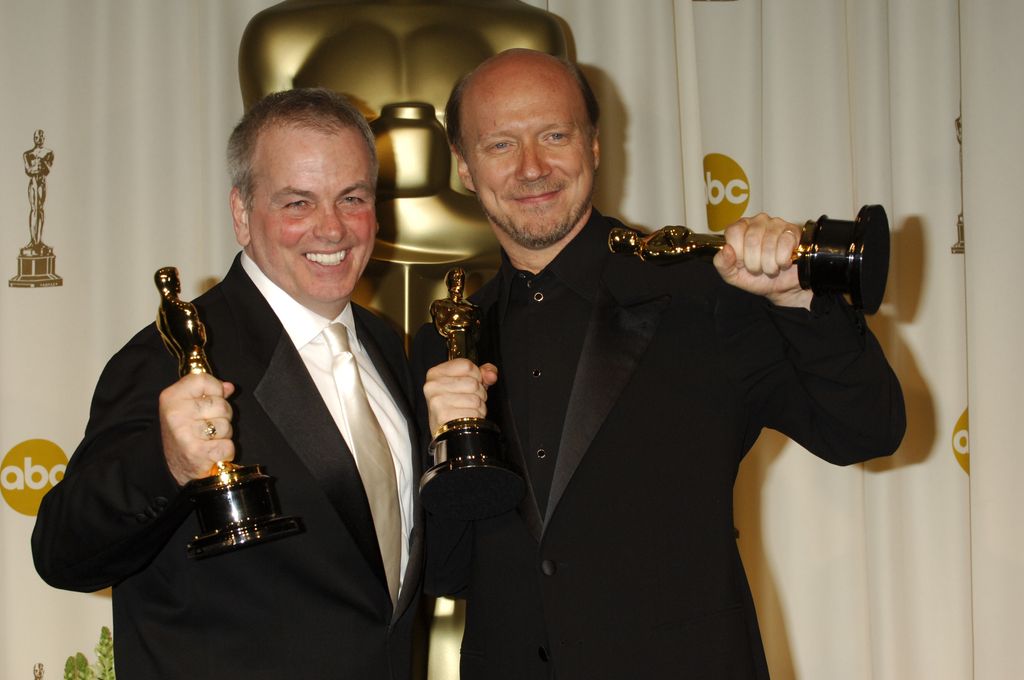

MORESCO: So we win the Best Original Screenplay Oscar, Paul gives a lovely speech, and it’s my time at the microphone. And they cut to a commercial. The only thing I had really cared about was thanking my parents, my wife, and my friends from the old neighborhood in Hell’s Kitchen. But I never got the chance. The win was really bittersweet for me.

SCHULMAN: Then our editor, Hughes Winborne, won. Someone told me that whoever wins the editing Oscar is also a reliable indicator for Best Picture.

HAGGIS: It’s the end of the show and I’m sitting across from the Brokeback producers. I turn to face them so I could applaud and not be caught looking like an asshole on camera. I’m all ready to clap for Ang Lee, and I hear Jack Nicholson say, “And the Oscar goes to … Crash.” I felt someone stand up behind me, and it’s my wife. I was so confused. “She loved Brokeback Mountain that much?” And then I realized, “Oh my God, we won.” I had no speech, so thank God Cathy had prepared. The room was thunderous.

SCHULMAN: Before we left the house that morning I told my husband, “There’s an open document on my computer. Can you print it and grab it?” What was actually open on my computer was not my speech but a list of statistics about genocide in Darfur. At the time I was working on my next movie, Darfur Now. That’s what I had with me that night. (Laughs)

PEÑA: I actually wasn’t invited to the show. Everyone else in the cast were all big stars. I was nobody [laughs]. So instead I watched it at a viewing party on La Cienega. My agency at the time had set it up for me to attend, but at the door they wouldn’t let me in. “Sorry, man.” I’m like “No, I’m in Crash. I swear!” Finally they let me in. I got a drink and sat by myself. When we won, I screamed like when the Bears won the Super Bowl in ’86. I was the only one cheering, and people were staring at me. They just went back drinking their drinks.

FRASER: I was in Mexico City that night working on a movie with Sarah Michelle Gellar and Andy Garcia. Sarah had her Blackberry and tells me, “Fraser, Crash just won Best Picture.” Suddenly she called over these mariachi players; people were honking horns and shouting, “That’s Brendan, he’s in that movie Crash, it just won Best Picture!” It was like a scene from It’s a Wonderful Life. [Laughs.]

MORESCO: Later in the night, Paul says, “Come on, Bobby, smile! We just won the fucking Best Picture Oscar.” And I couldn’t. But I’m not angry anymore. The next day about 40 of us went to Palm Springs and spend a weekend together with the Oscar. It all turned out fine.

SCHULMAN: The craziest part was walking into the Vanity Fair party. Mick Jagger hugged me. Everyone knew my face. I still think of that room as being filled with caricature drawings. They were handing out In-N-Out Burgers, so it was essentially every famous person I’ve ever seen in one room eating burgers. The next morning when I had to return my jewelry, like Cinderella, I ran into a girl who said, “Did you see that woman who won Best Picture last night?” And I said, “That was me!”

HAGGIS: A few days after the Oscars, [author] Annie Proulx wrote a piece in The Guardian newspaper complaining about Brokeback not winning Best Picture. Million Dollar Baby had won every single award the previous year except my category, Best Adapted Screenplay, and you didn’t see me trashing Sideways. I thought it was all in quite poor taste. And then the theory came out that the Academy was homophobic and that’s why Brokeback didn’t win. It was the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard in my life. There were two films that year, Brokeback and Capote, that had gay protagonists. How could they even get nominated if voters hated gay people? [Editor’s note: Proulx’s rep sent along this statement: “Annie won’t be able to talk to you, but all I can say is that Crash might have won the Academy Award but Brokeback Mountain is the film that has endured.”]

TABACK: Voters are more private when they are supporting a movie that wasn’t as well-reviewed. If critics say something is great, we also like to say it’s great. That’s human nature. But in the privacy of your own home, you can really take in and vote on a film that resonates with you. Also, voters like to support an underdog, and that’s what Crash was. It passed the “smell test” in terms of its being a contemporary awards film. It wasn’t a period piece; it didn’t take place in a far-off land. So while it may not have been a fine piece of art to some, it certainly resonated with people. And it still holds up.

SCHULMAN: I know people were angry about us winning. But I am one of only a few women to win Best Picture who wasn’t married to or related to the director. Also, it was an outsider movie that didn’t have a frame of it touched by a studio. Also I think one of the only other Best Picture winners that was like that was Chariots of Fire, and that’s very cool.

ORTENBERG: I got about 90 percent support from my peers. And the backlash I felt I quickly and easily chalked up to sour grapes. The ones who make excuses aren’t the ones who win.

FELTHEIMER: We’d won Oscars before Crash. Seeing Halle Berry win Best Actress for Monster’s Ball was very exciting. Also, we own Summit now, so we have two Best Picture wins including The Hurt Locker and Crash. And this year we have La La Land. I wouldn’t mind a three-peat. [Laughs.]

MORESCO: I immediately got more offers than ever after winning. You definitely worry less. And by the way, it turns out that Paul and I were both right: Crash was a movie anda television show. It became a drama on Starz in 2008 starring Dennis Hopper.

HAGGIS: I said no to many big projects after the Oscars. Big, big, big, big ones that I should’ve said yes to, but I’m an idiot. I won’t tell you which ones. [Laughs.] I wasthrilled to get hired to write Casino Royale a couple years later — I like doing things that people don’t expect me to do — but I fail so much more often than I succeed. I’ve got several screenplays sitting in the drawer that just aren’t good enough. It’s always hard. Always. Also, to this day I can’t watch anything I’ve written or directed after it’s done. Even Million Dollar Baby. I think Clint [Eastwood] did a great job, and I know it’s good! But I just can’t watch it.

BRIDGES: So much of what we dealt with in Crash as a culture we are dealing with today. I’ve even heard of schools showing it to their students, and that’s very powerful. It’s what I got into acting to do. To make people think. We need to be uncomfortable. I think the film also set a precedent for a lot of films and shows we’ve seen since that feature a mix of races and ethnicities in their casts. The diverse cast of the Fast and Furious movies that I’ve been a part of maybe wouldn’t exist without Crash. It taught Hollywood that audiences of color don’t only want to see one thing. People, no matter who they are, want to see real-life situations that they can relate to.

PENA: I thought that my career would be years and years of recycling gangster characters. Then Crash wins Best Picture and someone like Oliver Stone wants me to play Will Jimeno in World Trade Center. The guy who made Born on the Fourth of July,Platoon, and Wall Street wanted to meet me.

YARI: Then I had to go through being sued. [Editor’s note: In 2011, a Los Angeles judge ruled that Yari was in breach of contract and owed about $12 million to Haggis, Moresco, and Fraser for failing to pay them profits. Yari had also been denied a producer credit on the movie by the Producers Guild of America, which resulted in his not making the cut as one of the winners of the movie’s Best Picture Oscar.] That was my thanks for making Paul’s movie when everyone turned it down. It was very unpopular of me to have gone after the board members of the Academy producers’ division, which ruled that the PGA ultimately could determine who the Oscar went to. It was very kiss-the-ring kind of stuff. But I wasn’t going after the Academy’s membership; I was going after the people running it to force them to behave properly.

MORESCO: In the end, were we better than those other movies? No. Did we win the Oscar? Yeah. So what? Nobody wanted to make Crash. Nobody wanted to make Million Dollar Baby. Paul and I sat in his little office together every day, and we’d come up with these stories that we felt we loved and hopefully somebody else would love. And we stuck with it. I hope others take a lesson from all that. You just have to not give up. Nobody can stop you from writing, directing, or producing. Nobody. They can only stop you from getting paid. [Laughs.]

HAGGIS: I’m still very proud of the movie, but people are always asking me, “Do you think it should have won Best Picture?” What the hell am I supposed to say? “Yes. I think it’s the best picture of all time! Thank you for asking!” All I can say is that I’m terribly honored to be among those other nominees. I mean, look at those other films — Brokeback Mountain, Good Night, and Good Luck, Capote, Munich — they’re all fucking great movies. And I’m so glad everyone at Lionsgate ignored me about not campaigning for Crash, because I have two Oscars sitting at home.

*A version of this article appears in the November 28, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.