Hung Ga

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Also known as | Hung Ga, Hung Gar, Hung Kuen, Hung Ga Kuen, Hung Gar Kuen | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | Striking | ||||||||||||

| Country of origin | China | ||||||||||||

| Creator | Hung Hei-gun[1][2] | ||||||||||||

| Famous practitioners | (see below) | ||||||||||||

| Parenthood | Shaolin Kung Fu, Nanquan, Five Animal forms,[2] Bak Fu Pai (White Tiger Kung Fu),[1] Fujian White Crane,[3] Mok Gar (additional influence for Wong Fei Hung lineage) | ||||||||||||

| Descendant arts | Choy ga, Fut Gar, Hung Fut,[1] Jow-Ga Kung Fu | ||||||||||||

| Olympic sport | No | ||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | |||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Hung family | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Alternative name | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | |||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | immense fist | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

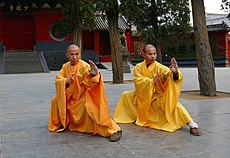

Hung Ga Kuen (Cantonese) or Hongjiaquan (Mandarin) (Chinese:

It is best known for its low and stable positions, its powerful attacks mainly developed with the upper limbs, many blocks and also the work of internal energy.[4][5] Its techniques are influenced by Bak Fu Pai (White Tiger Kung Fu) as well as Fujian White Crane.[1][3] In addition, the style takes up postures that imitate the other five classic animals of Shaolin quan: the tiger, the crane, the leopard, the snake and the bear, as well as hand forms of the dragon style qi-gong and it's simultaneous double strikes.[7][2]

Hung Gar Kuen is represented in the world in mainly four family branches; Tang Fung, Lam, Chiu and Lau. What the four have in common is that they have branched out from the most famous Hung Gar master of them all, Wong Fei-hung. Despite differences between these family branches, they strive for the same goal, to preserve one of the richest martial arts from China.

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese martial arts (Wushu) |

|---|

|

Characteristics and features

[edit]Hung Ga's technique employs the simultaneous use of attack and blocking, where the block is occasionally used as an conjunctive attack on the opponent. For instance, if a Hung Ga practitioner receives an strike to his upper body (or head), they can meet the incoming force with their own block, which is delivered with such force that it will overwhelm the opponent's own defensive abilities. The aim is to seriously injure the opponent or inflict such intense pain it will weaken the opponent's retaliation.[1]

The hallmarks of Hung Ga are strong stances, notably the horse stance, or "si ping ma" (

Traditionally, students spent anywhere from several months to three years in stance training, often sitting only in horse stance from half an hour to several hours at a time, before learning any forms. Each form could then take a year or so to learn, with weapons learned last. In current times, this mode of instruction is generally considered impractical for students, who have other concerns beyond practicing kung fu. However, some instructors still follow traditional guidelines and make stance training the majority of their beginner training.[1]

Historical origins

[edit]Hung Ga's earliest beginnings have been traced to the 17th century in southern China. More specifically, legend has it that a Shaolin monk, Jee Sin Sim See (”sim see” = zen teacher) was at the heart of Hung Ga's emergence. Jee Sin Sim See was alive during a time of fighting in the Qing dynasty. He practiced the arts during an era when the Shaolin Temple had become a refuge for those that opposed the ruling class (the Manchus), allowing him to practice in semi-secrecy. When the Shaolin temple was burned down, many fled to the Southern affiliated Shaolin temple in the Fukien Province of Southern China along with him. There it is believed Jee Sin Sim See trained several people, including non-Buddhist monks, also called Shaolin Layman Disciples, in the art of Shaolin Kung Fu.

Of course, Jee Sin Sim See was hardly the only person of significance that had fled to the temple and opposed the Manchus. Along with this, tea merchant Hung Hei-gun also took refuge there, where he trained under Jee Sin Sim See. Eventually, Hung Hei-gun became Jee Sin Sim See's most prodigious student.

That said, legend has it that Jee Sin Sim See also taught four others, whom in their entirety became the founding fathers of the five southern Shaolin styles: Hung Ga, Choy Ga, Mok Ga, Li Ga and Lau Ga. Luk Ah-choi was one of these students.[8]

According to one of the origin legends, Hung Hei-guan combined the Shaolin tiger techniques (Fok Fu Kuen,

Because the character "Hung" (

The Hung Mun claimed to be founded by survivors of the destruction of the Shaolin Temple, and the martial arts its members practiced came to be called "Hung Ga" and "Hung Kuen".

Its popularity in modern times is mainly associated with the Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei-hung, a Hung Ga master.

The Hung Ga curriculum of Wong Fei-hung

[edit]The Hung Ga curriculum that Wong Fei-hung learned from his father consisted of

Single Hard Fist, Double Hard Fist, Taming the Tiger Fist (

Wong distilled his father's empty-hand material along with the material he learned from other masters into the "pillars" of Hung Ga, four empty-hand routines that constitute the core of Hung Ga instruction in the Wong Fei-hung lineage: Taming the Tiger Fist, Tiger Crane Paired Form Fist, Five Animal Fist, and Iron Wire Fist. Each of those routines is described in the sections below.

"

- pinyin: gōng zì fú hǔ quán; Yale Cantonese: gung ji fuk fu kuen.

The long routine Taming the Tiger trains the student in the basic techniques of Hung Ga while building endurance. It is said to go at least as far back as Jee Sin Sim See, who is said to have taught Taming the Tiger—or at least an early version of it—to both Hung Hei-gun and Luk Ah-choi.

The "

Tiger Crane Paired Form Fist

- pinyin: hǔ hè shuāng xíng quán; Yale Cantonese: fu hok seung ying kuen.

Tiger Crane builds on Taming the Tiger, adding "vocabulary" to the Hung Ga practitioner's repertoire. Wong Fei-hung choreographed the version of Tiger Crane handed down in the lineages that descend from him. He is said to have added to Tiger Crane the bridge hand techniques and rooting of the master Tit Kiu Saam as well as long arm techniques, attributed variously to the Fat Ga, Lo Hon, and Lama styles. Tiger Crane Paired Form routines from outside Wong Fei-hung Hung Ga still exist.

Five Animal Fist

- pinyin: wǔ xíng quán; Yale Cantonese: ng ying keun / pinyin: wǔ xíng wǔ háng quán; Yale Cantonese: ng ying ng haang keun; Ng Ying Kungfu, Five Animal Kung Fu (Chinese:

五 形 功 夫 )

This routine serve as a bridge between the external force of Tiger Crane and the internal focus of Iron Wire. "Five Animals" (literally "Five Forms") refers to the characteristic Five Animals of the Southern Chinese martial arts: Dragon, Snake, Tiger, Leopard, and Crane. "Five Elements" refers to the five classical Chinese elements: Earth, Water, Fire, Metal, and Wood.

The Hung Ga Five Animal Fist was choreographed by Wong Fei-hung and expanded by Lam Sai-wing (

Iron Wire Fist

- pinyin: tiě xiàn quán; Yale Cantonese: Tit Sin Keun.

Iron Wire builds internal power and is attributed to the martial arts master Leung Kwan (

Wong Fei-hung weapon of choice was primarily the Fifth Brother Eight Trigram Pole (

Branches of Hung Kuen

[edit]The curricula of different branches of Hung Ga differ tremendously with regard to routines and the selection of weapons, even within the Wong Fei-hung lineage.

Just as those branches that do not descend from Lam Sai-wing do not practice the Five Animal Five Element Fist. Those branches that do not descend from Wong Fei-hung, are sometimes called "old Hung Kuen" or "village" Hung Kuen, do not practice the routines he choreographed, nor do the branches that do not descend from Tit Kiu Saam practice Iron Wire. Conversely, the curricula of some branches have grown through the addition of further routines by creation or acquisition.

Nevertheless, the various branches of the Wong Fei-hung lineage still share the Hung Ga foundation he systematized. Lacking such a common point of reference, the "village" styles of Hung Kuen show even greater variation.

The curriculum which Jee Sin Sim See taught Hung Hei-gun is said to have comprised Tiger style, Luohan style, and Taming the Tiger routine. Exchanging material with other martial artists allowed Hung to develop or acquire Tiger Crane Paired Form routine, a combination animal routine, Southern Flower Fist, and several weapons.

According to Hung Ga tradition, the martial arts that Jee Sin Sim See originally taught Hung Hei-gun were short range and the more active footwork, wider stances, and long range techniques commonly associated with Hung Ga were added later. It is said to have featured "a two-foot horse," that is, narrow stances, and routines whose footwork typically took up no more than four tiles' worth of space.

Hasayfu Hung Ga

Five-Pattern Hung Kuen

Tiger Crane Paired Form

Ang Lian-huat attributes the art to Hung Hei-gun's combination of the Tiger style he learned from Jee Sin Sim See with the Crane style he learned from his wife, whose name is given in Hokkien as Tee Eng-choon. Like other martial arts that trace their origins to Fujian (e.g. Fujian White Crane, Five Ancestors), this style uses San Chian as its foundation.

Wong Kiew-kit trace their version of the Tiger Crane routine, not to Hung Hei-gun or Luk Ah-choi, but to their senior classmate Harng Yein.

Northern Hung Kuen

The dissemination of Hung Kuen

[edit]The dissemination of Hung Kuen in Southern China, and its Guangdong and Fujian Provinces in particular, is due to the concentration of anti-Qing activity there.

The Hung Mun began life in the 1760s as the Heaven and Earth Society, whose founders came from the prefecture of Zhangzhou in Fujian Province, on its border with Guangdong, where one of its founders organized a precursor to the Heaven and Earth Society in Huizhou.

Guangdong and Fujian remained a stronghold of sympathizers and recruits for the Hung Mun, even as it spread elsewhere in the decades that followed.

Though the members of the Hung Clan almost certainly practiced a variety of martial arts styles, the composition of its membership meant that it was the characteristics of Fujianese and Cantonese martial arts that came to be associated with the names "Hung Kuen" and "Hung Ga".

Regardless of their differences, the Hung Kuen lineages of Wong Fei-hung, Yuen Yik-kai, Leung Wah-chew, and Jeung Kei-ji (

Wong Fei-Hung lineages

[edit]Lam Sai-wings Lineage mainly descends from Wong Fei-hung.

- Chan Hon-chung (

- Lau Jaam Hung Kuen (

- Lam Cho (

(Among Tang Kwok-wah's students currently teaching in the area are Winchell Ping Chiu-woo (

- Chiu Kau (

Dang Fong (

See also

[edit]- The five major family styles of southern Chinese martial arts

- Jee Sin Sim See

- Wong Kei-ying

- Wong Fei-hung

- Lam Sai-wing

- Tang Fung

- Fu Jow Pai - Tiger Claw System

- Cantonese culture

- Hak Fu Mun - Black Tiger System

References

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Habersetzer, Gabrielle; Habersetzer, Roland (2004) [2000]. Encyclopédie technique, historique, biographique et culturelle des arts martiaux de l'Extrême-Orient [Technical, historical, biographical and cultural encyclopedia of the martial arts of the Far East] (in French). Amphora. ISBN 9782851806604.

- Kennedy, Brian; Guo, Elizabeth (2005). Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. pp. 152–153. ISBN 1-55643-557-6.

[quote] Fujian province was reputed to be home to one of the Shaolin temples that figure so prominently in martial arts folklore. As a result, Fujian province and the adjacent province of Guangdong were the birthplace and home of many southern Shaolin systems, at least according to the oral folklore. A military historian might be of the opinion that the reason those two southern provinces had so many different systems of martial arts had more to do with the fact that, during the Qing Dynasty, rebel armies were constantly being formed and disbanded in those provinces, resulting in a wide variety of people who had some training and interest in martial arts.

- Rene Ritchie, Robert Chu and Hendrik Santo. "Wing Chun Kuen and the Secret Societies". Wingchunkuen.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2006. Retrieved August 14, 2005.

- Wing Lam (2003). Southern Shaolin Kung Fu Ling Nam Hung Gar. Copyright 2003 Wing Lam Enterprises. p. 241. ISBN 1-58657-361-6.

- Hagen Bluck "Hung Gar Kuen - Im Zeichen des Tigers und des Kranichs"; 1998/2006 MV-Verlag, Edition Octopus, ISBN 978-3-86582-427-1

- Lam Sai-wing. "Iron Thread. Southern Shaolin Hung Gar Kung Fu Classics Series". Second Edition, 2007. Paperback, 188 pages. ISBN 978-1-84799-192-8 / Original edition: Hong Kong, 1957; translated from Chinese in 2002 - 2007

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Crudelli, Chris (2008). The Way of the Warrior. Dorling Kindersley Limited. p. 111. ISBN 9781405337502.

- ^ a b c Ashley Martin (2013). The Complete Martial Arts Training Manual: An Integrated Approach. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0555-3.

Hung Gar is a Southern style named after the Hung family (gar means family) that created it. It was created by Hung Hei Gun in the 18th century combining the best techniques from Tiger style and Crane Style. Hung Gar uses the five animal forms.

- ^ a b c Habersetzer & Habersetzer 2004, p. 51-53.

- ^ a b Eng, Paul (2018) [2004]. Kung Fu Basics: Everything You Need to Get Started in Kung Fu - from Basic Kicks to Training and Tournaments. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462920181.

Hung Gar ("Hung Family Style") Hung Gar was, and still is, one of the most famous and popular Southern systems. It is good for all ages and all body structures. While it is considered by some to be relatively slow, it is powerful. It includes isometric and dynamic tension exercises that not only develop strong arms and legs, but also generate considerable internal power.

- ^ a b Kit, Wong Kiew (2022) [1996]. Art of Shaolin Kung Fu: The Secrets of Kung Fu for Self-Defense, Health, and Enlightenment. Tuttle Publishing. p. 39-40. ISBN 9781462923526.

- ^ Lewis, P. (1993). Martial Arts of the Orient. MMB. ISBN 9781853751271 Page 34

- ^ Kong, B., Ho, E. H. (1973). Hung Gar Kung-Fu. Ohara Publications. ISBN 9780897500388 Page 13

- ^ Vinh-Hoi Ngo (1996). Martial Arts Masters: The Greatest Teachers, Fighters, and Performers. Lowell House Juvenile. ISBN 1-5656-5559-1.

- ^ Chu, R., Ritchie, R., Wu, Y. (2015). Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532 Page 114.