Editorials

‘Cry Wolf’: An Early 2000s Teen Slasher in All the Best and Worst Ways [You Aughta Know]

Hello, true believers, and welcome to You Aughta Know, a column dedicated to the decade that is now two full decades behind us. That’s right, it’s time to take a look back at one of the most overlooked decades of horror. Follow along as I do my best to explore the horror titles that made up the 2000s.

We were riding out the last few weeks of summer 2005, and mid-September saw both the songs “Gold Digger” by Kanye West and “Don’t Cha” by The Pussycat Dolls flood the radio waves and become major musical staples. While the film Stay starred a pre-hyped Ryan Gosling and mid-hype Ewan McGregor, as well as the always excellent Naomi Watts, the week of the 16th also saw the release of a little slasher film that leaned heavily on the internet obsessed masses. That’s right, Cry Wolf (stylized as Cry_Wolf) quietly snuck in and cleaned up at the box office.

We all know the 2000s was a wild era that we’ll never be able to replicate and one of the most bonkers things that came out of it was the cross-promotional efforts put forward by numerous strangely interested parties. One of these gloriously bizarre concoctions was the Chrysler Million Dollar Film Festival. Yes, you read that right; Chrysler, as in the car company. Teamed up with Universal, the automobile manufacturer decided to give a first time filmmaker a million dollars towards their debut effort in a contest that saw thousands of entries. The task was quite simple, really: film a short that spotlighted a PT Cruiser.

I’m not even making this up. The car that is the punchline of decades worth of ridicule was the main participant of these shorts that young visionaries were creating, all in the hope of even having a shot at being able to fund a feature length film. USC graduates Jeff Wadlow and Beau Bauman, the director and screenwriter respectively, pieced together the short The Tower of Babble, which was just the first leg of a long race to get Cry Wolf made. The Tower of Babble got them accepted into the festival which in turn then challenged them to compete against the nine other semi-finalists in an “extreme filmmaking” contest. During this round, creatives had to cast, shoot, edit and premiere a film in 10 days that would debut at Cannes. Total. Insanity.

Jeff Wadlow’s second short, Manual Labor, landed him a spot as one of the five finalists that then participated in a summer long boot camp with mentors. Grouped up with Charlie Lyons and Suzann Ellis of Bring It On fame, Wadlow and Bauman were originally going to adapt a play. When the playwright dropped the rights in the eleventh hour, Wadlow came up with the idea of a ‘professional liars club’ and the duo quickly cobbled together the necessary early pitch for the slasher inspired horror. The team wrote the entire script in two weeks, as well as filming a five minute treatment as part of the pitch, with Topher Grace and Estella Warren starring. Pitched as a send up of The Boy Who Cried Wolf with Craven teen scream sensibilities, Wadlow and Bauman eventually won the contest after presenting the pitch at the Toronto Film Festival.

The film itself is about a group of teenagers, mostly rich and bored, who spend their spare time playing a lying game of deduction and coercion (we would largely relate it to the now popular Werewolf or Mafia games). Owen is a transfer student with a problematic past who gets swept into the game while pursuing Dodger, a queen bee of sorts. When Owen and Dodger decide to take the game to the next level, creating a new game based around a real life murder and a fictional killer named ‘The Wolf,’ the two use instant messaging to quickly connect the entire school into their macabre web of lies.

Diving deep into the production of this film is fascinating. The crew hit a number of massive snags along the way yet still produced what is ultimately a pretty slick and well done murder-mystery piece that is heavily inspired by both the meta-horror upstarts from the Scream era as well as the much more grounded slasher revival that was starting with films like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre remake. After being told to switch the setting out of L.A. and away from twentysomethings, the creators settled at a boarding school in Virginia. They had to push shoots back numerous times due to storms and power outages, heavy security was required because of Bon Jovi being on set, and they once even had to set up shop in a Kinkos due to weather conditions. And money. They kept running out of money. This is why the heavy use of Apple products and AOL (we’ll come back to that) are so prominent in the film; they had to create partnerships with these companies to allow for some more room when it came to budget.

Cry Wolf stars a young cast on the precipice of breaking into larger roles. Our main character Owen, the mischievous but gold hearted newbie, is played by Julian Morris, who would go on to become a central character in ABC Family mystery Pretty Little Liars (as well as the Sorority Row remake), while his love interest and genius level puppeteer Dodger is portrayed by Lindy Booth, who had just come out of Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead and would later venture back into the fantasy genre fare in The Librarians. The teen drama love doesn’t stop there as Jared Padalecki from CW’s Supernatural and Paul James from ABC Family classic Greek are supporting characters. Veteran everyman Gary Cole and rock legend himself Jon Bon Jovi round out the adult roles in this teen centric thriller.

Cry Wolf feels so 2000s in all the best and worst ways. Using AIM instant messaging as a central plot device, the movie is also chock full of spiky hair, crushed velvet booty shorts and, of course, PT Cruisers. The movie feels extra spooky because of its east coast Autumn setting, so we’re treated to brownstone buildings amongst the brown and yellow leaves of Fall; hell, we even get a Halloween dance scene. It is a clever little whodunnit, even if the central conceit is dated and silly, but the killer is a particularly daunting figure and the execution of the kills have a fun premise running through them. Being the mid-2000s, however, the film is also bogged down with homophobia and some outdated terminology that will make you cringe when watching.

The movie would eventually release with a tie-in to an actual mobile game, partnered with AOL and their legendary messenger program, a lofty and ambitious partnership that few remember but still is a joy to think about. Cry Wolf isn’t groundbreaking in any way but it is a lot of fun. Mixing in a glossy young cast with a creepy murder-mystery makes for a good time and the entire aesthetic of the boarding school in fall really helps kick the movie up another notch as a particularly pleasing slasher flick. Think of the movie as the 2000s version of April Fool’s Day, just updated with early high speed internet antics and blossoming young television stars, and you’ve got yourself another enjoyable slashic from the aughts.

Editorials

Seeing Things: Roger Corman and ‘X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes’

When the news of Roger Corman’s passing was announced, the online film community immediately responded with a flood of tributes to a legend. Many began with the multitude of careers he helped launch, the profound influence he had on independent cinema, and even the cameos he made in the films of Corman school “graduates.”

Tending to land further down his list of achievements and influences a bit is his work as a director, which is admittedly a more complicated legacy. Yes, Corman made some bad movies, no one is disputing that, but he also made some great ones. If he was only responsible for making the Poe films from 1960’s The Fall of the House of Usher to 1964’s The Tomb of Ligeia, he would be worthy of praise as a terrific filmmaker. But several more should be added to the list including A Bucket of Blood (1959) and Little Shop of Horrors (1960), which despite very limited resources redefined the horror comedy for a generation. The Intruder (1962) is one of the earliest and most daring films about race relations in America and a legitimate masterwork. The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967) combine experimental and narrative filmmaking in innovative and highly influential ways and also led directly to the making of Easy Rider (1969).

Finally, X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963) is one of the most intelligent, well crafted, and entertaining science fiction films of its own or any era.

Officially titled X, with “The Man with the X-Ray Eyes” only appearing in the promotional materials, the film arose from a need for variety while making the now-iconic Poe Cyle. Corman put it this way in his indispensable autobiography How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime:

“If I had spent the entire first half of the 1960s doing nothing but those Poe films on dimly let gothic interior sets, I might well have ended up as nutty as Roderick Usher. Whether it was a conscious motive or not, I avoided any such possibilities by varying the look and themes of the other films I made during the Poe cycle—The Intruder, for example—and traveling to some out-of-the-way places to shoot them.”

Some of these films, in addition to Corman’s masterpiece The Intruder (1962), included Atlas and Creature from the Haunted Sea in 1961, The Young Racers (1963), The Secret Invasion (1964), and of course X, which was originally brought to him (as was often the case) only as a title from one of his bosses, James H. Nicholson. Corman and writer Ray Russell batted the idea presented in the title around for a couple days before coming to this idea also described in Corman’s book:

“He’s a scientist deliberately trying to develop X-Ray or expanded vision. The X-Ray vision should progress deeper and deeper until at the end there is a mystical, religious experience of seeing to the center of the universe, or the equivalent of God.”

While Corman worked on other projects, Russell and Robert Dillon wrote the script, which has a surprising profundity rarely found in low-budget science fiction films of the era. Like The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) before it and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) after, X grapples with nothing less than humanity’s miniscule place in an endless cosmos. These films also posit that, despite our infinitesimal nature, we still matter.

In some senses, X plays out like an extended episode of The Twilight Zone. Considering Corman’s work with regular contributors to that show Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont during this era, this makes a lot of sense. It begins with establishing the conceit of the film—X-ray vision discovered by a well-meaning research scientist Dr. James Xavier, played by Academy Award Winner Ray Milland. The concept is then developed in ways that are innocuous, fun, or helpful to humanity or himself. As the effect of the eyedrops that expand his vision cumulate, Xavier is able to see into his patients’ bodies and see where surgeries should be performed, for example. He is also able to see through people’s clothes at a late-evening party and eventually cheat at blackjack in Las Vegas. Finally, the film takes its conceit to its extreme, but logical, conclusion—he keeps seeing further and further until he sees an ever-watching eye at the center of the universe—and builds to a shock ending. And like many of the best episodes of The Twilight Zone, X is spiritual, existential, and expansive while remaining grounded in way that speaks to our humanity.

Two sections of the film in particular underscore these qualities. The first begins after Xavier escapes from his medical research facility after being threatened with a malpractice suit. He hides out as a carnival sideshow attraction under the eye of a huckster named Crane, brilliantly played by classic insult comedian Don Rickles in one of his earliest dramatic roles. At first, a blindfolded Xavier reads audience comments off cards, which he can see because of his enhanced vision. Corman regulars Dick Miller and Jonathan Haze appear as hecklers in this scene. He soon leaves the carnival and places himself into further exile, but Crane brings people to him who are infirmed or in pain and seeking diagnosis. Crane then collects their two bucks after Xavier shares his insights. This all acts as a kind of comment on the tent revivalists who hustled the desperate out of their meager earnings with the promise of healing. Now in the modern era, it is still effective as these kinds of charlatans have only changed venues from canvas tents to megachurches and nationwide television.

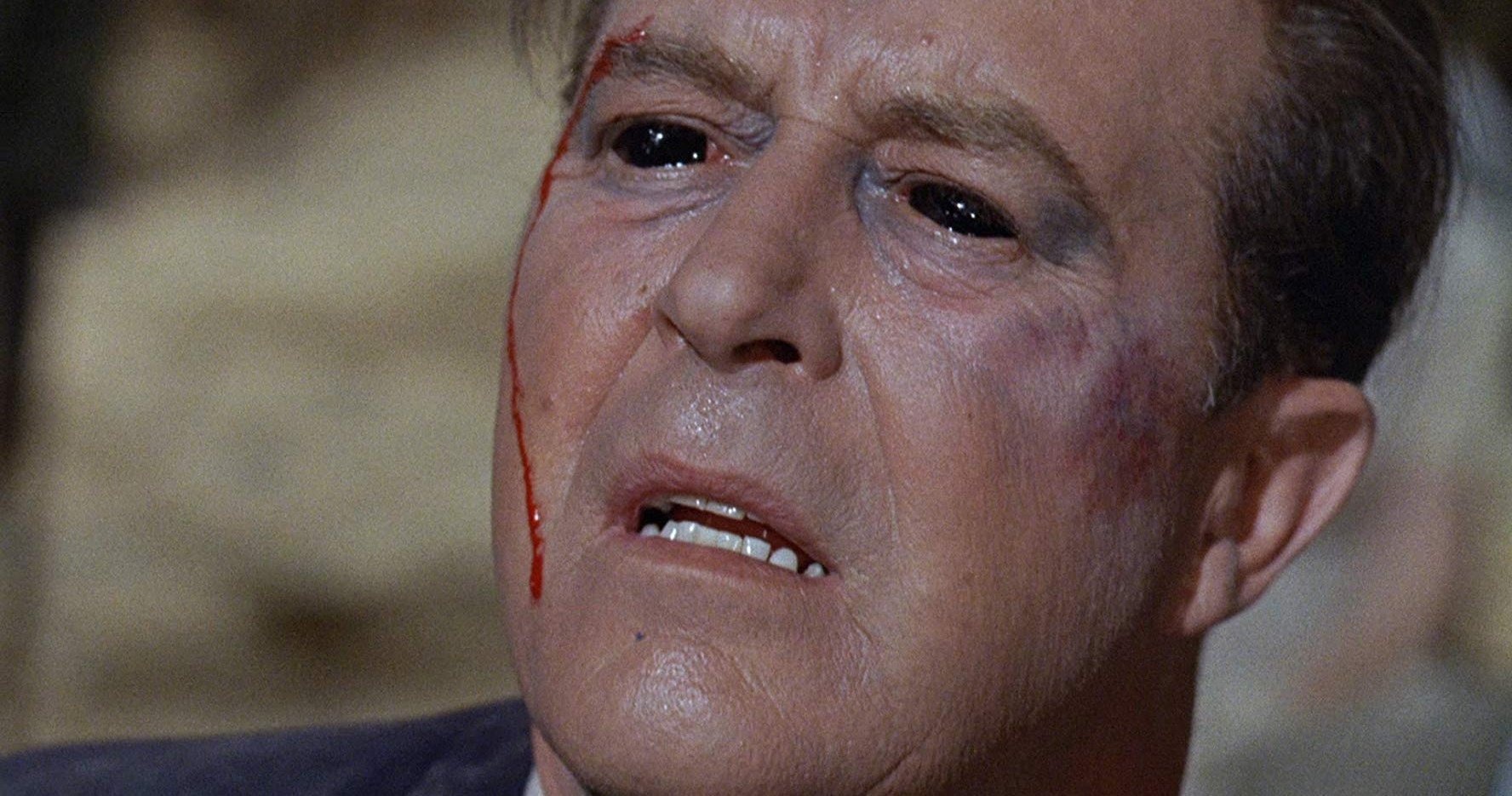

The other sequence comes right at the end. After speeding his way out of Las Vegas under suspicion of cheating at cards, Xavier gets in a car accident and wanders out into the Nevada desert. He finds his way to a tent revival and is asked by the preacher, “do you wish to be saved?” He responds, “No, I’ve come to tell you what I see.” He speaks of seeing great darknesses and lights and an eye at the center of the universe that sees us all. The preacher tells him that he sees “sin and the devil,” and calls for him to literally follow the scripture that says, “if your eye causes you to sin, pluck it out.” Xavier’s hands fly to his face, and the last moment of the film is a freeze frame of his empty, bloody eye sockets.

At this point, Xavier is seeing the unfathomable secrets of the universe. Taken in a spiritual sense, he is the first living human to see the face of God since Adam before being exiled from the Garden of Eden. But neither the scientific community nor the spiritual one can accept him. The scientific community sees him as a pariah, one who has meddled in a kind of witchcraft because he has advanced further and faster than they have been able to. The spiritual leader believes he has seen evil because he cannot fathom a person seeing God when he, a man of God, is unable to do so himself. The one man who can supply answers to the eternal questions about humanity’s place in the universe, questions asked by science and religion alike, is rendered impotent by both simply because they are unable to see. The myopia of both camps is the greater tragedy of X. Xavier himself perhaps finally has relief, but the rest of humanity will continue to live in darkness, a blindness that is not physical but the result of a lack of knowledge that Xavier alone could provide. In other words, he could help them see, or to use religious terminology, give sight to the blind. Rumor has it that a line was cut from the final film in which Xavier, after plucking out his eyes, cries out “I can still see!” A horrifying line to be sure, but it also would have kept the tragedy personal. In the final version, the tragedy is cosmic.

I usually try to keep myself out of the articles in this column, but allow me to break convention if I may. Roger Corman’s death affected me in ways that I did not expect. With his advanced age I knew the news would come down sooner rather than later, but maybe a part of me expected him to outlive us all. Corman’s legacy loomed large, but he never seemed to believe too much of his own press. I’ve heard many stories over the years of his gentle, even retiring demeanor, his ability to have tea and conversation with volunteers at conventions, his reaching out to people he liked and respected when they felt alone in the world. I never had the pleasure of meeting or speaking with him myself, but I did get to speak with his daughter Catherine and sneak in a few questions about her father. It was fascinating to hear about the kind of man he was, the things that interested him, and the community he created in his home and studio.

X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes was the first Corman movie I ever heard of, though I saw it for the first time many years later. When my family first got a VCR back in the mid-80s, my parents quickly learned about my obsession with horror movies, though at the time I was too afraid to actually see most of them. One day while browsing the horror section at the gigantic, pre-Blockbuster video store we had a membership with, my dad said, “Oo! The Man with the X-Ray Eyes! That’s a great one.” For whatever reason, we didn’t pick the video up that day, but I never forgot that title. Then I read about it in Stephen King’s Danse Macabre and, though he spoils the entire movie in that book (which is fine, it’s not really that kind of movie) I was enthralled and became a bit obsessed with seeing it. Of course, by then it was a lot harder to track down the film, so I only had King’s plot description, a few scattered details from my dad’s memory, and my imagination to go by. When I finally did see it, the film did not disappoint. Sure, the special effects, clothes, music, and styles are pretty dated, but the themes and messages of the film are endlessly fascinating and relevant.

It may seem obvious, but X is a film about seeing and all the different meanings of that word. There are those things seen by the physical eye but there is so much more to it than that limited meaning. It asks questions of what we see with imagination, the spiritual, and intellectual eye. It explores what society does to people who can truly see. Some are deified while others are condemned and ostracized. And then there are those questions of if there is something out there that sees us. Is it a force of good or evil or indifference? Is there anything at all out there that looks for us as much as we look for it? It may just be a silly little low-budget science fiction film, but somehow X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes has the power to provoke thought and imagination in a way few films can. It may even have the power to help us see in ways we could only imagine.

In Bride of Frankenstein, Dr. Pretorius, played by the inimitable Ernest Thesiger, raises his glass and proposes a toast to Colin Clive’s Henry Frankenstein—“to a new world of Gods and Monsters.” I invite you to join me in exploring this world, focusing on horror films from the dawn of the Universal Monster movies in 1931 to the collapse of the studio system and the rise of the new Hollywood rebels in the late 1960’s. With this period as our focus, and occasional ventures beyond, we will explore this magnificent world of classic horror. So, I raise my glass to you and invite you to join me in the toast.

You must be logged in to post a comment.