While researching for my latest book, Claude Coats: Walt Disney’s Imagineer—The Making of Disneyland: From Toad Hall to the Haunted Mansion and Beyond, I discovered some fascinating facts about Disney Legend Claude Coats. Aside from being an artist and designer who, for more than half a century, was one of the most prolific creative talents at The Walt Disney Company, he was also an accomplished fine artist, set designer, and model maker. In his spare time, he painted personal work that evolved in technique and medium over the decades. There were other fascinating facts that I learned about Coats that were surprising to me and Imagineering colleagues who vetted my manuscript.

I thought it would be fun to offer up five of those discoveries that presented themselves through the process of making this book. So here goes:

1) Coats was hired as a fireman aboard a steamship to the Orient. Coats got hired as a fireman stoking the boilers aboard the S.S. President Cleveland in the summer of 1934. Built originally as a troop transport ship for WWI, the President Cleveland went through a conversion to a passenger and cargo vessel operated by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company during the 1930s. Coats was initially hired as a “scab worker” because of a longshoremen’s strike underway at the port.

According to Alan Coats, while his father was trying to board the ship, “he was stopped at the gangplank by a surly mob of striking longshoremen. ‘Where do you think you’re going, buddy?’ Thinking fast on his feet, he answered, ‘The captain owes me money.’ The captain was not well-liked and probably owed others, so they let Coats pass to try to collect.”

The ship departed from San Francisco on Wednesday, June 27, 1934, then sailed to Honolulu, Hawaii. From Honolulu, Coats went to Yokohama, and from there, the boat took him to Shanghai, China. He spent some time, possibly a few days, in Shanghai taking photographs with a tiny camera he had brought with him. Upon his return, he used those photos as references for several watercolor paintings, one of which has survived. The lanky 6-foot, 6-inch, 160-pound Coats must have stood out, in both Japan and China, not just as an American abroad but also for his sheer height.

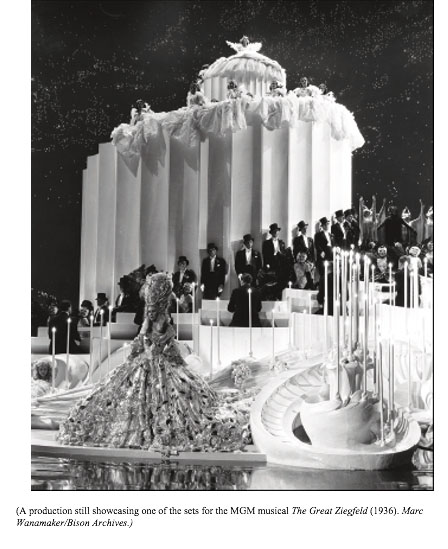

2) Coats worked in the MGM art department as an assistant art director but quit for less money to work for Disney. Coats was hired as an assistant to art director John Harkrider, who was working on a Universal musical film production. Harkrider is probably best remembered for his elaborate nightclub sets with the shiny black floors upon which Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers danced in Swing Time (1936). The film in early development when Coats joined Harkrider was The Great Ziegfeld (1936), which was planned as a big-budget bio-picture of the legendary Broadway producer, starring William Powell.

Only one studio could produce such an extravaganza, and the project went into turnaround to MGM Studios. Coats continued on the project by joining Harkrider in Hollywood’s largest art department at MGM, headed by legendary art director and production designer Cedric Gibbons. He honed his drafting and painting skills, learned about the workings of a movie studio’s art department and the camaraderie of working with other artists. The Great Ziegfeld would go on to win the Best Picture Oscar for 1936.

While at MGM, Coats met two other future Disney artists working in the art department, Herb Ryman and Ken Anderson. At the time, Ryman was an artist and illustrator at MGM until he quit to visit and tour China, possibly based on the stories of Coats’ earlier experiences. On his return from that trip in 1938, he was hired by Walt Disney himself after viewing Ryman’s exhibition of paintings of his China trip at Chouinard Art Institute. Anderson’s tenure at MGM, briefly overlapping with Coats, was short. He joined The Walt Disney Studios in 1934, where he started working on Silly Symphony cartoons, including The Goddess of Spring (1934) and the Academy Award-winning Three Orphan Kittens (1935).

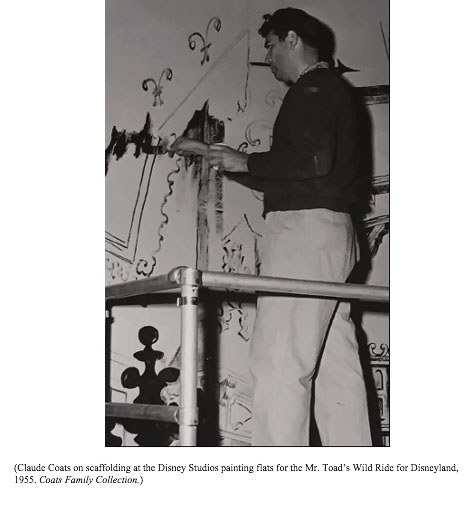

3) Walt Disney personally assigned Coats and Ken Anderson to Paint the original flats for Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride attraction. At Walt Disney’s request, Coats was asked to create a three-dimensional model of Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride for the soon to open Disneyland theme park. Since Coats had painted backgrounds on the film The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949) just six years earlier, he was familiar with the film. He assumed his tabletop model would be used as a guide for the set design by the company hired to paint the scenic flats for the attraction. After Walt had approved the model, Coats was under the impression he was done and would move on to the Studios’ next film project.

Several weeks later, while talking to his Studios colleague Ken Anderson, who had dropped by to chat, Claude’s career path would forever change. According to one account, Walt Disney came into Claude’s office, his “bangs” apparently falling into his face, “eyes pinched with irritation. He was faced with yet another delay in park construction, and opening day was approaching.” He pointed at Coats and Anderson and said, “Grosh Studios can’t do Mr. Toad, so you guys do it.” This rather theatrical account is one of several versions of the encounter and is more dramatic than what happened, as we will see later.

R.L. Grosh & Sons Scenic Studio, now known as Grosh Scenic Studios, had been hired by Disney to create the painted scenics for Snow White’s Adventures ride, Peter Pan (later renamed Peter Pan’s Flight), and Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride. All three would be dark ride attractions for the Fantasyland area at Disneyland, which was under construction. But because of time and labor constraints, Grosh came back to Walt and said they didn’t have the capacity to get Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride finished in time. There had also been speculation that Grosh had difficulty matching the blacklight paints to the film’s color palette.

Regardless, it was an all-hands-on-deck situation. With Walt backed into a corner by the scenic subcontractor, Claude Coats became one of the art directors and show designers for the new theme park. His career as an animation background artist and color stylist ended, and he became what was eventually coined an Imagineer.

4) Coats solved an impossible problem in Rainbow Caverns that made Walt Disney utter one of his famous quotes. In the Rainbow Falls section of the Mine Train Through Nature’s Wonderland attraction in Frontierland, Coats had one wall where all six colors came down side-by-side. The rocket scientist Heinz Haber, a consultant for the Disney space pictures in the 1950s, looked at Coats’ model and said, ‘It’s statistically impossible. It’ll all mix together and go gray in a week. You can’t separate those colors. If it splashes just a little bit, for the amount of hours you’re gonna [sic] run this ride, all the colors will intermingle.’”

The next time Walt came by to see how things were progressing with the finale, Coats said, “…well, Heinz Haber is telling me that this one’s statically impossible.” Walt just looked at the model, then looked at Coats and said one of his now most famous quotes, “Well, it’s always fun to do the impossible.” With that, Walt walked off, leaving Coats tofigure out just how they could solve the issue and to make the “impossible” possible.

Coats and the team solved the problem by using rubberized hog’s hair supported on a grid with baffles between each fluorescent dye color, and it finally worked. Rubberized hog’s hair is similar to those coarse scrubbing pads used to clean pots and pans. “The loose density of ‘hair’ in the coarse pads trapped the falling water, thus preventing the predicted splashes and spattering from occurring. The results allowed each color to remain pure without mixing together to spoil the amazing effect,” Tony Baxter said. The colored dyes stayed separated. “It was quite tricky to do,” Bob Gurr said, “…once it worked, it worked really well, and to my knowledge, I don’t think anybody ever tried a thing like that ever again.”

5) Coats became an Official Air Force Artist in 1961. The United States Air Force (USAF) requested several Disney artists through the Society of Illustrators of Los Angeles to participate in a program depicting the USAF’s spirit throughout the world. Artists would create scenes in watercolor, oil, acrylic, or mixed media of what they observed during visits to USAF “activities throughout the world.” The USAF was enlisting dozens of noted artists from around the United States to participate in this program by way of the Society of Illustrators of New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Coats and fellow Disney artists Al Dempster and Art Riley were selected to participate in this program.

Coats and Dempster had the choice assignment to go to Japan to observe USAF activities and record them in paintings. While Riley appears to have drawn the short straw, he was assigned to paint Edwards Air Force Base in the desert of Southern California. It certainly was not as exotic as Japan. By July 1961, Coats and Dempster were in Japan.

Coats made a total of three pictures for the 1961 program: Rice Paddies Near Beppu, Silver Jets Over Fuji, and Water Survival School Numazu, which he donated to the United States Air Force Art Collection. All three paintings are featured in the new book about Coats.

An embroidered cloth patch designating Coats as a “USAF OFFICIAL ARTIST” was given to him after his Japan trip.

Coats Family Collection.

Lt. Colonel George C. Bales, USAF, wrote to Coats and said, “you certainly have made an outstanding addition to our collection.” He also enclosed a circular shoulder patch, which Bales designed and hand-made in Germany, that read “USAF Official Artist” around a plane’s image. “You can add it to your collection,” Bales wrote, “or have it framed for the wall,…how about that?”

There are many more exciting and surprising factoids about Claude Coats and his relationship with Walt Disney during the making of Disneyland in my latest book, which releases this Fall. For more information or to order a signed copy of the book, visit www.theoldmillpress.com.

What they are saying about the Claude Coats book:

“… Claude Coats, once a background painter, was the master of ride environments… His work with Walt is presented here in rich detail and insightful writing, a story that moves from the early Disney films up to the Haunted Mansion.”

– Todd James Pierce, Author of Three Years in Wonderland: The Disney Brothers, C. V. Wood, and the Making of the Great American Theme Park

“In the pantheon of Imagineers who worked directly with Walt Disney, Claude Coats stands tall… Long deserving of a dedicated book about his work at WED, Coats was a master creator who drove the designs behind a plethora of Disneyland classics. Any designer or theme park aficionado worth their salt would do well to study the work of this often overlooked titan of Imagineering.”

–Christopher Merritt, author of Marc Davis In His Own Words:

Imagineering the Disney Theme Parks

“This marvelous book abounds with all I wish I had known about the genius of Claude Coats when I first came to Walt Disney Imagineering in 1976… And how his talented, generous, and humble spirit infused the atmosphere of Imagineering with his unwavering optimism, his unique gift for problem-solving, his encouragement of young talent, and his commitment to teamwork on every creative project. He was a very special kind of pioneer-artist-designer and it’s never too late to celebrate that!”

– Peggie Fariss, Creative Executive (retired),

Walt Disney Imagineering

©2021 David A. Bossert

Portions of this article have been extracted from the author’s book, Claude Coats: Walt Disney’s Imagineer—The Making of Disneyland: From Toad Hall to the Haunted Mansion and Beyond. All footnote attributions are noted in the book.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

Those are definitely five things I never knew about Imagineer Claude Coats. In fact, I’m a little embarrassed to admit that I didn’t even recognise his name. So it’s good that your book is bringing wider attention to the accomplishments of this extraordinary artist.

As much as I love Japan, I don’t agree that Art Riley in any way “drew the short straw” in being assigned to paint Edwards Air Force Base, where a lot of exciting developments in aerospace research were going on at this time. Coats, on the other hand, arrived in southern Japan right in the middle of the rainy season, unquestionably the worst time of year to travel there. His painting of the egrets in the rice paddy really captures the oppressive humidity of the season. Beppu is a hot springs resort town, so Coats would at least have been able to enjoy that traditional experience; but Numazu, where he painted the Water Survival School, was completely destroyed by American bombing raids in 1945 and would have provided little in the way of “exotic” vistas, except for some nice views of Mt. Fuji, assuming the weather cleared long enough to allow it. Nevertheless, his work would certainly be important documentation of the Air Force’s role in not only guiding the Japanese Self Defence Forces, but in rebuilding the country during the postwar period.

I’m very impressed by the Air Force’s support of the fine arts through its patronage of the Society of Illustrators. This isn’t the sort of thing I thought they ever did; but, given that the U.S. Air Force has its own chamber orchestra (quite a good one, actually), I shouldn’t be surprised.

Paul,

Thank you for reading the piece. My comment on drawing the “short straw” was in relation to Art Riley not traveling off to some exotic place like Japan. Certainly, there was major research on flight and aerospace being done at Edwards Air Force base, which was not that far afield from the Disney Burbank studio. As an artist, I think it would have been more exciting to travel to a distant place, like Claude Coats and Al Dempster did, regardless of the time of year.

Best,

-Dave

Another thing that the USAF did which may surprise people in 2021 was their in-house involvement in animation production, to the extent that at one time they actually had their own proprietary animation peg system, slightly different than either the Oxberry or Acme peg registration systems. The excellent, if now dated, reference book “Animation: Its Concepts, Methods and Uses,” by Dr. Roy P. Madsen, illustrates the US Air Force peg system with several photos and an illuminating text.