Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (German: [ˈɡeɔɐ̯k ˈvɪlhɛlm ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈheːɡəl]; August 27, 1770 – November 14, 1831) was a German philosopher, and a major figure in German Idealism. His historicist and idealist account of reality revolutionized European philosophy and was an important precursor to Continental philosophy and Marxism.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel | |

|---|---|

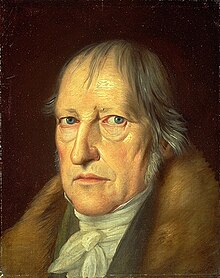

Portrait by Jakob Schlesinger, 1831 | |

| Born | August 27, 1770 |

| Died | November 14, 1831 (aged 61) |

| Nationality | German |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | German idealism Founder of Hegelianism Historicism Precursor to German Historism |

Main interests | Logic · Aesthetics · Religion Philosophy of history Metaphysics · Epistemology Political philosophy |

Notable ideas | Absolute idealism · Dialectic Sublation · Master/slave |

| Signature | |

Hegel developed a comprehensive philosophical framework, or "system", of absolute idealism to account in an integrated and developmental way for the relation of mind and nature, the subject and object of knowledge, psychology, the state, history, art, religion, and philosophy. In particular, he developed the concept that mind or spirit manifested itself in a set of contradictions and oppositions that it ultimately integrated and united, without eliminating either pole or reducing one to the other. Examples of such contradictions include those between nature and freedom, and between immanence and transcendence.

Hegel influenced writers of widely varying positions, including both his admirers and his detractors.[2] Karl Barth compared Hegel to a "Protestant Aquinas".[3] Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote, "All the great philosophical ideas of the past century—the philosophies of Marx and Nietzsche, phenomenology, German existentialism, and psychoanalysis—had their beginnings in Hegel...".[4] Michel Foucault has contended that contemporary philosophers may be "doomed to find Hegel waiting patiently at the end of whatever road we travel".[5] Hegel's influential conceptions are those of speculative logic or "dialectic", "absolute idealism". They include "Geist" (spirit), negativity, sublation (Aufhebung in German), the "Master/Slave" dialectic, "ethical life" and the importance of history.

Life

Early years

Childhood

Hegel was born on August 27, 1770 in Stuttgart, in the Duchy of Württemberg in southwestern Germany. Christened Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, he was known as Wilhelm to his close family. His father, Georg Ludwig, was Rentkammersekretär (secretary to the revenue office) at the court of Karl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg.[6] Hegel's mother, Maria Magdalena Louisa (née Fromm), was the daughter of a lawyer at the High Court of Justice at the Württemberg court. She died of a "bilious fever" (Gallenfieber) when Hegel was thirteen. Hegel and his father also caught the disease but narrowly survived.[7] Hegel had a sister, Christiane Luise (1773–1832), and a brother, Georg Ludwig (1776–1812), who was to perish as an officer in Napoleon's Russian campaign of 1812.[8]

At age of three Hegel went to the "German School". When he entered the "Latin School" two years later, he already knew the first declension, having been taught it by his mother.

In 1776 Hegel entered Stuttgart's Gymnasium Illustre. During his adolescence Hegel read voraciously, copying lengthy extracts in his diary. Authors he read include the poet Klopstock and writers associated with the Enlightenment, such as Christian Garve and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. Hegel's studies at the Gymnasium were concluded with his Abiturrede ("graduation speech") entitled "The abortive state of art and scholarship in Turkey."[9]

Tübingen (1788-93)

At the age of eighteen Hegel entered the Tübinger Stift (a Protestant seminary attached to the University of Tübingen), where two fellow students were to become vital to his development - poet Friedrich Hölderlin, and philosopher-to-be Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling. Sharing a dislike for what they regarded as the restrictive environment of the Seminary, the three became close friends and mutually influenced each other's ideas. They watched the unfolding of the French Revolution with shared enthusiasm. Schelling and Hölderlin immersed themselves in theoretical debates on Kantian philosophy, from which Hegel remained aloof. Hegel at this time envisaged his future as that of a Popularphilosoph, i.e., a "man of letters" who serves to make the abstruse ideas of philosophers accessible to a wider public; his own felt need to engage critically with the central ideas of Kantianism did not come until 1800.

Bern (1793–96) and Frankfurt (1797–1801)

Having received his theological certificate (Konsistorialexamen) from the Tübingen Seminary, Hegel became Hofmeister (house tutor) to an aristocratic family in Bern (1793–96). During this period he composed the text which has become known as the "Life of Jesus" and a book-length manuscript titled "The Positivity of the Christian Religion". His relations with his employers becoming strained, Hegel accepted an offer mediated by Hölderlin to take up a similar position with a wine merchant's family in Frankfurt, where he moved in 1797. Here Hölderlin exerted an important influence on Hegel's thought.[10] While in Frankfurt Hegel composed the essay "Fragments on Religion and Love".[11] In 1799 he wrote another essay entitled "The Spirit of Christianity and Its Fate",[12] unpublished during his lifetime.

Also in 1797, the unpublished and unsigned manuscript of "The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism" was written. It was written in Hegel's hand but thought to have been authored by Hegel, Schelling, Hölderlin, or by all three.

Career years

Jena, Bamberg and Nuremberg: 1801–1816

In 1801 Hegel came to Jena with the encouragement of his old friend Schelling, who held the position of Extraordinary Professor at the University there. Hegel secured a position at the University as a Privatdozent (unsalaried lecturer) after submitting a Habilitationsschrift (dissertation) on the orbits of the planets. Later in the year Hegel's first book, The Difference Between Fichte's and Schelling's Systems of Philosophy, was completed. He lectured on "Logic and Metaphysics" and gave joint lectures with Schelling on an "Introduction to the Idea and Limits of True Philosophy" and held a "Philosophical Disputorium". In 1802 Schelling and Hegel founded a journal, the Kritische Journal der Philosophie ("Critical Journal of Philosophy"), to which they each contributed pieces until the collaboration was ended when Schelling left for Würzburg in 1803.

In 1805 the University promoted Hegel to the position of Extraordinary Professor (unsalaried), after Hegel wrote a letter to the poet and minister of culture Johann Wolfgang von Goethe protesting at the promotion of his philosophical adversary Jakob Friedrich Fries ahead of him.[13] Hegel attempted to enlist the help of the poet and translator Johann Heinrich Voß to obtain a post at the newly renascent University of Heidelberg, but failed; to his chagrin, Fries was later in the same year made Ordinary Professor (salaried) there.[14]

His finances drying up quickly, Hegel was now under great pressure to deliver his book, the long-promised introduction to his System. Hegel was putting the finishing touches to this book, the Phenomenology of Spirit, as Napoleon engaged Prussian troops on October 14, 1806, in the Battle of Jena on a plateau outside the city. On the day before the battle, Napoleon entered the city of Jena. Hegel recounted his impressions in a letter to his friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:

I saw the Emperor – this world-soul – riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it . . . this extraordinary man, whom it is impossible not to admire.[15]

Although Napoleon chose not to close down Jena as he had other universities, the city was devastated and students deserted the university in droves, making Hegel's financial prospects even worse. The following February Hegel's landlady Christiana Burkhardt (who had been abandoned by her husband) gave birth to their son Georg Ludwig Friedrich Fischer (1807–31).[16]

In March 1807, aged 37, Hegel moved to Bamberg, where Niethammer had declined and passed on to Hegel an offer to become editor of a newspaper, the Bamberger Zeitung. Hegel, unable to find more suitable employment, reluctantly accepted. Ludwig Fischer and his mother (whom Hegel may have offered to marry following the death of her husband) stayed behind in Jena.[17]

He was then, in November 1808, again through Niethammer, appointed headmaster of a Gymnasium in Nuremberg, a post he held until 1816. While in Nuremberg Hegel adapted his recently published Phenomenology of Spirit for use in the classroom. Part of his remit being to teach a class called "Introduction to Knowledge of the Universal Coherence of the Sciences", Hegel developed the idea of an encyclopedia of the philosophical sciences, falling into three parts (logic, philosophy of nature, and philosophy of spirit).[18]

Hegel married Marie Helena Susanna von Tucher (1791–1855), the eldest daughter of a Senator, in 1811. This period saw the publication of his second major work, the Science of Logic (Wissenschaft der Logik; 3 vols., 1812, 1813, 1816), and the birth of his two legitimate sons, Karl Friedrich Wilhelm (1813–1901) and Immanuel Thomas Christian (1814–1891).

Heidelberg and Berlin: 1816–1831

Having received offers of a post from the Universities of Erlangen, Berlin, and Heidelberg, Hegel chose Heidelberg, where he moved in 1816. Soon after, in April 1817, his illegitimate son Ludwig Fischer (now ten years old) joined the Hegel household, having thus far spent his childhood in an orphanage.[19] (Ludwig's mother had died in the meantime.)[20]

Hegel published The Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Outline (1817) as a summary of his philosophy for students attending his lectures at Heidelberg.

Sketch by Franz Kugler

In 1818 Hegel accepted the renewed offer of the chair of philosophy at the University of Berlin, which had remained vacant since Johann Gottlieb Fichte's death in 1814. Here he published his Philosophy of Right (1821). Hegel devoted himself primarily to delivering his lectures; his lecture courses on aesthetics, the philosophy of religion, the philosophy of history, and the history of philosophy were published posthumously from lecture notes taken by his students. His fame spread and his lectures attracted students from all over Germany and beyond.

Hegel was appointed Rector of the University in 1830, when he was 60. He was deeply disturbed by the riots for reform in Berlin in that year. In 1831 Frederick William III decorated him for his service to the Prussian state. In August 1831 a cholera epidemic reached Berlin and Hegel left the city, taking up lodgings in Kreuzberg. Now in a weak state of health, Hegel seldom went out. As the new semester began in October, Hegel returned to Berlin, with the (mistaken) impression that the epidemic had largely subsided. By November 14 Hegel was dead. The physicians pronounced the cause of death as cholera, but it is likely he died from a different gastrointestinal disease.[21] He is said to have uttered the last words "And he didn't understand me" before expiring.[22] In accordance with his wishes, Hegel was buried on November 16 in the Dorotheenstadt cemetery next to Fichte and Solger.

Hegel's son Ludwig Fischer had died shortly before while serving with the Dutch army in Batavia; the news of his death never reached his father.[23] Early the following year Hegel's sister Christiane committed suicide by drowning. Hegel's remaining two sons - Karl, who became a historian, and Immanuel, who followed a theological path - lived long and safeguarded their father's Nachlaß and produced editions of his works.

Thought

Freedom

Hegel's thinking can be understood as a constructive development within the broad tradition that includes Plato and Immanuel Kant. To this list one could add Proclus, Meister Eckhart, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Plotinus, Jakob Böhme, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. What all these thinkers share, which distinguishes them from materialists like Epicurus, the Stoics, and Thomas Hobbes, and from empiricists like David Hume, is that they regard freedom or self-determination both as real and as having important ontological implications, for soul or mind or divinity. This focus on freedom is what generates Plato's notion (in the Phaedo, Republic, and Timaeus) of the soul as having a higher or fuller kind of reality than inanimate objects possess. While Aristotle criticizes Plato's "Forms", he preserves Plato's cornerstones of the ontological implications for self-determination: ethical reasoning, the soul's pinnacle in the hierarchy of nature, the order of the cosmos, and an assumption with reasoned arguments for a prime mover. Kant imports Plato's high esteem of individual sovereignty to his considerations of moral and noumenal freedom, as well as to God. All three find common ground on the unique position of humans in the scheme of things, known by the discussed categorical differences from animals and inanimate objects.

In his discussion of "Spirit" in his Encyclopedia, Hegel praises Aristotle's On the Soul as "by far the most admirable, perhaps even the sole, work of philosophical value on this topic".[24] In his Phenomenology of Spirit and his Science of Logic, Hegel's concern with Kantian topics such as freedom and morality, and with their ontological implications, is pervasive. Rather than simply rejecting Kant's dualism of freedom versus nature, Hegel aims to subsume it within "true infinity", the "Concept" (or "Notion": Begriff), "Spirit," and "ethical life" in such a way that the Kantian duality is rendered intelligible, rather than remaining a brute "given."

The reason why this subsumption takes place in a series of concepts is that Hegel's method, in his Science of Logic and his Encyclopedia, is to begin with basic concepts like Being and Nothing, and to develop these through a long sequence of elaborations, including those already mentioned. In this manner, a solution that is reached, in principle, in the account of "true infinity" in the Science of Logic's chapter on "Quality", is repeated in new guises at later stages, all the way to "Spirit" and "ethical life", in the third volume of the Encyclopedia.

In this way, Hegel intends to defend the germ of truth in Kantian dualism against reductive or eliminative programs like those of materialism and empiricism. Like Plato, with his dualism of soul versus bodily appetites, Kant pursues the mind's ability to question its felt inclinations or appetites and to come up with a standard of "duty" (or, in Plato's case, "good") which transcends bodily restrictiveness. Hegel preserves this essential Platonic and Kantian concern in the form of infinity going beyond the finite (a process that Hegel in fact relates to "freedom" and the "ought"[25]), the universal going beyond the particular (in the Concept), and Spirit going beyond Nature. And Hegel renders these dualities intelligible by (ultimately) his argument in the "Quality" chapter of the "Science of Logic." The finite has to become infinite in order to achieve reality. The idea of the absolute excludes multiplicity so the subjective and objective must achieve synthesis to become whole. This is because, as Hegel suggests by his introduction of the concept of "reality",[26] what determines itself—rather than depending on its relations to other things for its essential character—is more fully "real" (following the Latin etymology of "real": more "thing-like") than what does not. Finite things don't determine themselves, because, as "finite" things, their essential character is determined by their boundaries, over against other finite things. So, in order to become "real", they must go beyond their finitude ("finitude is only as a transcending of itself"[27]).

The result of this argument is that finite and infinite—and, by extension, particular and universal, nature and freedom—don't face one another as two independent realities, but instead the latter (in each case) is the self-transcending of the former.[28] Rather than stress the distinct singularity of each factor that complements and conflicts with others—without explanation—the relationship between finite and infinite (and particular and universal, and nature and freedom) becomes intelligible as a progressively developing and self-perfecting whole.

Progress

The obscure writings of Böhme had a strong effect on Hegel. Böhme had written that the Fall of Man was a necessary stage in the evolution of the universe. This evolution was, itself, the result of God's desire for complete self-awareness. Hegel was fascinated by the works of Kant, Rousseau, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and by the French Revolution. Modern philosophy, culture, and society seemed to Hegel fraught with contradictions and tensions, such as those between the subject and object of knowledge, mind and nature, self and Other, freedom and authority, knowledge and faith, the Enlightenment and Romanticism. Hegel's main philosophical project was to take these contradictions and tensions and interpret them as part of a comprehensive, evolving, rational unity that, in different contexts, he called "the absolute idea" or "absolute knowledge".

According to Hegel, the main characteristic of this unity was that it evolved through and manifested itself in contradiction and negation. Contradiction and negation have a dynamic quality that at every point in each domain of reality—consciousness, history, philosophy, art, nature, society—leads to further development until a rational unity is reached that preserves the contradictions as phases and sub-parts by lifting them up (Aufhebung) to a higher unity. This whole is mental because it is mind that can comprehend all of these phases and sub-parts as steps in its own process of comprehension. It is rational because the same, underlying, logical, developmental order underlies every domain of reality and is ultimately the order of self-conscious rational thought, although only in the later stages of development does it come to full self-consciousness. The rational, self-conscious whole is not a thing or being that lies outside of other existing things or minds. Rather, it comes to completion only in the philosophical comprehension of individual existing human minds who, through their own understanding, bring this developmental process to an understanding of itself. Hegel's thought is revolutionary to the extent that it is a philosophy of absolute negation: as long as absolute negation is at the center, systematization remains open, and makes it possible for human beings to became subjects.[29]

"Mind" and "Spirit" are the common English translations of Hegel's use of the German "Geist". Some[who?] have argued that either of these terms overly "psychologize" Hegel,[citation needed] implying a kind of disembodied, solipsistic consciousness like ghost or "soul." Geist combines the meaning of spirit—as in god, ghost or mind—with an intentional force. In Hegel's early philosophy of nature (draft manuscripts written during his time at the University of Jena), Hegel's notion of "Geist" was tightly bound to the notion of "Aether" from which Hegel also derived the concepts of space and time; however in his later works (after Jena) Hegel did not explicitly use his old notion of "Aether" any more.[30]

Central to Hegel's conception of knowledge and mind (and therefore also of reality) was the notion of identity in difference, that is that mind externalizes itself in various forms and objects that stand outside of it or opposed to it, and that, through recognizing itself in them, is "with itself" in these external manifestations, so that they are at one and the same time mind and other-than-mind. This notion of identity in difference, which is intimately bound up with his conception of contradiction and negativity, is a principal feature differentiating Hegel's thought from that of other philosophers.

Civil society

Hegel made the distinction between civil society and state in his Elements of the Philosophy of Right.[31] In this work, civil society (Hegel used the term "bürgerliche Gesellschaft" though it is now referred to as Zivilgesellschaft in German to emphasize a more inclusive community) was a stage in the dialectical relationship that occurs between Hegel's perceived opposites, the macro-community of the state and the micro-community of the family.[32] Broadly speaking, the term was split, like Hegel's followers, to the political left and right. On the left, it became the foundation for Karl Marx's civil society as an economic base;[33] to the right, it became a description for all non-state aspects of society, including culture, society and politics.[34] This liberal distinction between political society and civil society was followed by Alexis de Tocqueville.[33] In fact, Hegel's distinctions as to what he meant by civil society are often unclear. For example, while it seems to be the case that he felt that a civil-society such as the German society in which he lived was an inevitable movement of the dialectic, he made way for the crushing of other types of "lesser" and not fully realized types of civil society, as these societies were not fully conscious or aware, as it were, as to the lack of progress in their societies. Thus, it was perfectly legitimate in the eyes of Hegel for a conqueror, such as Napoleon, to come along and destroy that which was not fully realized.

Heraclitus

According to Hegel, "Heraclitus is the one who first declared the nature of the infinite and first grasped nature as in itself infinite, that is, its essence as process. The origin of philosophy is to be dated from Heraclitus. His is the persistent Idea that is the same in all philosophers up to the present day, as it was the Idea of Plato and Aristotle."[35] For Hegel, Heraclitus's great achievements were to have understood the nature of the infinite, which for Hegel includes understanding the inherent contradictoriness and negativity of reality, and to have grasped that reality is becoming or process, and that "being" and "nothingness" are mere empty abstractions. According to Hegel, Heraclitus's "obscurity" comes from his being a true (in Hegel's terms "speculative") philosopher who grasped the ultimate philosophical truth and therefore expressed himself in a way that goes beyond the abstract and limited nature of common sense and is difficult to grasp by those who operate within common sense. Hegel asserted that in Heraclitus he had an antecedent for his logic: "... there is no proposition of Heraclitus which I have not adopted in my logic."[36]

Hegel cites a number of fragments of Heraclitus in his Lectures on the History of Philosophy.[37] One to which he attributes great significance is the fragment he translates as "Being is not more than Non-being", which he interprets to mean

Sein und Nichts sei dasselbe

Being and non-being are the same.

Heraclitus does not form any abstract nouns from his ordinary use of "to be" and "to become" and in that fragment seems to be opposing any identity A to any other identity B, C, etc., which is not-A. Hegel, however, interprets not-A as not existing at all, not nothing at all, which cannot be conceived, but indeterminate or "pure" being without particularity or specificity.[38] Pure being and pure non-being or nothingness are for Hegel pure abstractions from the reality of becoming, and this is also how he interprets Heraclitus. This interpretation of Heraclitus cannot be ruled out, but even if present is not the main gist of his thought.

For Hegel, the inner movement of reality is the process of God thinking, as manifested in the evolution of the universe of nature and thought; that is, Hegel argued that, when fully and properly understood, reality is being thought by God as manifested in a person's comprehension of this process in and through philosophy. Since human thought is the image and fulfillment of God's thought, God is not ineffable (so incomprehensible as to be unutterable) but can be understood by an analysis of thought and reality. Just as humans continually correct their concepts of reality through a dialectical process, so God himself becomes more fully manifested through the dialectical process of becoming.

For his god Hegel does not take the logos of Heraclitus but refers rather to the nous of Anaxagoras, although he may well have regarded them the same, as he continues to refer to god's plan, which is identical to God. Whatever the nous thinks at any time is actual substance and is identical to limited being, but more remains to be thought in the substrate of non-being, which is identical to pure or unlimited thought.

The universe as becoming is therefore a combination of being and non-being. The particular is never complete in itself but to find completion is continually transformed into more comprehensive, complex, self-relating particulars. The essential nature of being-for-itself is that it is free "in itself"; that is, it does not depend on anything else, such as matter, for its being. The limitations represent fetters, which it must constantly be casting off as it becomes freer and more self-determining.[39]

Although Hegel began his philosophizing with commentary on the Christian religion and often expresses the view that he is a Christian, his ideas of God are not acceptable to some Christians, although he has had a major influence on 19th- and 20th-century theology. At the same time, an atheistic version of his thought was adopted instead by some Marxists, who, stripping away the concepts of divinity, styled what was left dialectical materialism, which some saw as originating in Heraclitus.

Religion

This section possibly contains original research. (October 2012) |

As a graduate of a Protestant seminary, Hegel’s theological concerns were reflected in many of his writings and lectures.[40] Hegel's thoughts on the person of Jesus Christ stood out from the theologies of the Enlightenment. In his posthumous book, The Christian Religion: Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion Part 3, he espouses that, "God is not an abstraction but a concrete God...God, considered in terms of his eternal Idea, has to generate the Son, has to distinguish himself from himself; he is the process of differentiating, namely, love and Spirit". This means that Jesus as the Son of God is posited by God over against himself as other. Hegel sees both a relational unity and a metaphysical unity between Jesus and God the Father. To Hegel, Jesus is both divine and Human. Hegel further attests that God (as Jesus) not only died, but "...rather, a reversal takes place: God, that is to say, maintains himself in the process, and the latter is only the death of death. God rises again to life, and thus things are reversed."

Walter Kaufmann has argued that there was great stress on the sharp criticisms of traditional Christianity appearing in Hegel's so-called early theological writings. Kaufmann admits that Hegel treated many distinctively Christian themes, and "sometimes could not resist equating" his conception of spirit (Geist) "with God, instead of saying clearly: in God I do not believe; spirit suffices me."[41] Kaufmann also points out that Hegel's references to God or to the divine—and also to spirit—drew on classical Greek as well as Christian connotations of the terms. Kaufmann goes on:

"In addition to his beloved Greeks, Hegel saw before him the example of Spinoza and, in his own time, the poetry of Goethe, Schiller, and Holderlin, who also liked to speak of gods and the divine. So he, too, sometimes spoke of God and, more often, of the divine; and because he occasionally took pleasure in insisting that he was really closer to this or that Christian tradition than some of the theologians of his time, he has sometimes been understood to have been a Christian"[42]

In addition to his beloved Greeks, Hegel saw before him the example of Spinoza and, in his own time, the poetry of Goethe, Schiller, and Holderlin, who also liked to speak of gods and the divine. So Hegel, too according to Kaufmann, sometimes spoke of God and, more often, of the divine; and because Hegel occasionally took pleasure in insisting that he was really closer to this or that Christian tradition than some of the theologians of his time, he has sometimes been understood to have been a Christian[43][44]

Kaufmann's own understanding of Hegel's disbelief in a supernatural God (which has been affirmed by other Hegel scholars such as Findlay, Tucker, C. Solomon, Hippolyte, Kojeve, Beiser, Pinkard, Westphal, and Wheat) is evidently to the contrary:

The religious views of the later Hegel were remote from all forms of traditional Christianity, but he no longer heeded his own emphatic dictum that philosophy should beware of being edifying, and tried to show that he could be more inspiring, and sound more Christian, than Schleiermacher and other liberal theologians. He came to emphasize what his philosophy had in common with Christianity—what is heard gladly. He had not always been a tired old man...[45]

Works

Hegel published four books during his lifetime: the Phenomenology of Spirit (or Phenomenology of Mind), his account of the evolution of consciousness from sense-perception to absolute knowledge, published in 1807; the Science of Logic, the logical and metaphysical core of his philosophy, in three volumes, published in 1812, 1813, and 1816 (revised 1831); Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, a summary of his entire philosophical system, which was originally published in 1816 and revised in 1827 and 1830; and the Elements of the Philosophy of Right, his political philosophy, published in 1820. During the last ten years of his life, he did not publish another book but thoroughly revised the Encyclopedia (second edition, 1827; third, 1830).[46]. All four are of considerable interest but the first two are unquestionably Hegel's masterpieces.[47]. In his political philosophy, he criticized Karl Ludwig von Haller's reactionary work, which claimed that laws were not necessary. He also published some articles early in his career and during his Berlin period. A number of other works on the philosophy of history, religion, aesthetics, and the history of philosophy were compiled from the lecture notes of his students and published posthumously. Hegel's thought is not just a philosophical system, but a system which knows about its own relationship to the rest of experience which is not philosophy, and knows above all that its own knowing cannot exhaust this relationship.[48]

The French Revolution for Hegel constitutes the introduction of real individual political freedom into European societies for the first time in recorded history. But precisely because of its absolute novelty, it is also unlimited with regard to everything that preceded it: on the one hand the upsurge of violence required to carry out the revolution cannot cease to be itself, while on the other, it has already consumed its opponent. The revolution therefore has nowhere to turn but onto its own result: the hard-won freedom is consumed by a brutal Reign of Terror. History, however, progresses by learning from its mistakes: only after and precisely because of this experience can one posit the existence of a constitutional state of free citizens, embodying both the benevolent organizing power of rational government and the revolutionary ideals of freedom and equality. Hegel's remarks on the French revolution led German poet Heinrich Heine to label him "The Orléans of German Philosophy".

Legacy

There are views of Hegel's thought as a representation of the summit of early 19th-century Germany's movement of philosophical idealism. It would come to have a profound impact on many future philosophical schools, including schools that opposed Hegel's specific dialectical idealism, such as Existentialism, the historical materialism of Marx, historism, and British Idealism.

Hegel's influence was immense both within philosophy and in the other sciences. Throughout the 19th century many chairs of philosophy around Europe were held by Hegelians, and Søren Kierkegaard, Ludwig Feuerbach, Marx, and Friedrich Engels—among many others—were all deeply influenced by, but also strongly opposed to, many of the central themes of Hegel's philosophy. After less than a generation, Hegel's philosophy was suppressed and even banned by the Prussian right-wing, and was firmly rejected by the left-wing in multiple official writings.

After the period of Bruno Bauer, Hegel's influence did not make itself felt again until the philosophy of British Idealism and the 20th century Hegelian Western Marxism that began with György Lukács. The more recent movement of communitarianism has a strong Hegelian influence.

Reading Hegel

Some of Hegel's writing were intended for those with advanced knowledge of philosophy, although his "Encyclopedia" was intended as a textbook in a university course. Nevertheless, like many philosophers, Hegel assumed that his readers would be well-versed in Western philosophy, up to and including René Descartes, Hume, Kant, Fichte, and Schelling. For those wishing to read his work without this background, introductions to and commentaries about Hegel can contribute to comprehension, although the reader is faced with multiple interpretations of Hegel's writings from incompatible schools of philosophy. The German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno devoted an essay to the difficulty of reading Hegel and asserted that there are certain passages where it is impossible to decipher what Hegel meant. Difficulties within Hegel's language and thought are magnified for those reading Hegel in translation, since his philosophical language and terminology in German often do not have direct analogues in other languages. For example, the German word "Geist" has connotations of both "mind" and "spirit" in English. English translators have to use the "phenomenology of mind" or "the phenomenology of spirit" to render Hegel's "Phaenomenologie des Geistes", thus altering the original meaning. Hegel himself argued, in his "Science of Logic", that the German language was particularly conducive to philosophical thought and writing.

One especially difficult aspect of Hegel's work is his innovation in logic. In response to Immanuel Kant's challenge to the limits of pure reason, Hegel developed a radically new form of logic, which he called speculation, and which is today popularly called dialectics. The difficulty in reading Hegel was perceived in Hegel's own day, and persists into the 21st century. To understand Hegel fully requires paying attention to his critique of standard logic, such as the law of contradiction and the law of the excluded middle. Many philosophers who came after Hegel and were influenced by him, whether adopting or rejecting his ideas, did so without fully absorbing his new speculative or dialectical logic.[citation needed]

According to Kaufmann, the basic idea of Hegel's works, especially the Phenomenology of the Spirit is that a philosopher should not "confine him or herself to views that have been held but penetrate these to the human reality they reflect." In other words, it is not enough to consider propositions, or even the content of consciousness; "it is worthwhile to ask in every instance what kind of spirit would entertain such propositions, hold such views, and have such a consciousness. Every outlook in other words, is to be studied not merely as an academic possibility but as an existential reality."[49]

Hegel is fascinated by the sequence Kaufmann writes:

How would a human being come to see the world this way or that? And to what extent does the road on which a point of view is reached color the view? Moreover, it should be possible to show how every single view in turn is one-sided and therefore untenable as soon as it is embraced consistently. Each must therefore give way to another, until finally the last and most comprehensive vision is attained in which all previous views are integrated. That way the reader would be compelled – not by rhetoric or by talk of compelling him, but by the successive examination of forms of consciousness – to rise from the lowest and least sophisticated level to the highest and most philosophical; and on the way he would recognize stoicism and skepticism, Christianity, and Enlightenment, Sophocles and Kant.[50]

Many sympathetic commentators have argued that this is surely one of the most imaginative and poetic conceptions ever to have occurred to any philosopher. Kaufmann even argues that the parallel between Hegel's Phenomenology and Dante's journey "through hell and purgatory to the blessed vision meets the eye." He also makes a comparison with Goethe's Faust claiming that "two quotations from ‘The First Part of the Tragedy’ could have served Hegel as mottoes." The first of these passages (lines 1770-75) Kaufmann argues Hegel knew from Faust: A Fragment (1790)":

And what is portioned out to all mankind,

I shall enjoy deep in myself, contain Within my spirit summit and abyss, Pile on my breast their agony and bliss,

And thus let my own self grow into theirs, unfettered[51]

though Kaufmann argues that Hegel would "scarcely have added, like Faust":

These lines express much of the spirit of the book Kaufmann writes: "Hegel is not treating us to a spectacle, letting various forms of consciousness pass in review before our eyes to entertain us as he considers it necessary to re-experience what the human spirit has gone through in history and he challenges the reader to join him in this Faustian undertaking." [53] Hegel asks readers not merely to read about such possibilities but according to Kaufmann, to "identify with each in turn until their own self has grown to the point where it is contemporary with world spirit. The reader, like the author, is meant to suffer through each position, and to be changed as he/she proceeds from one to the other. Mea res agitur: my own self is at stake. Or, as Rilke put it definitively in the last line of his great sonnet on an “Archaic Torso of Apollo”: du must dein Leben andern – you must change your life.” [54]

Left and Right Hegelianism

Some historians have spoken of Hegel's influence as represented by two opposing camps. The Right Hegelians, the allegedly direct disciples of Hegel at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, advocated a Protestant orthodoxy and the political conservatism of the post-Napoleon Restoration period. The Left Hegelians, also known as the Young Hegelians, interpreted Hegel in a revolutionary sense, leading to an advocation of atheism in religion and liberal democracy in politics.

In more recent studies, however, this paradigm has been questioned.[55] No Hegelians of the period ever referred to themselves as "Right Hegelians"; that was a term of insult originated by David Strauss, a self-styled Left Hegelian. Critiques of Hegel offered from the Left Hegelians radically diverted Hegel's thinking into new directions and eventually came to form a disproportionately large part of the literature on and about Hegel.[citation needed]

The Left Hegelians also spawned Marxism, which inspired global movements, encompassing the Russian Revolution, the Chinese Revolution, and myriad revolutionary practices up until the present moment.

Twentieth-century interpretations of Hegel were mostly shaped by British Idealism, logical positivism, Marxism, and Fascism. The Italian Fascist Giovanni Gentile, according to Benedetto Croce, "...holds the honor of having been the most rigorous neo-Hegelian in the entire history of Western philosophy and the dishonor of having been the official philosopher of Fascism in Italy."[56] However, since the fall of the USSR, a new wave of Hegel scholarship arose in the West, without the preconceptions of the prior schools of thought. Walter Jaeschke and Otto Pöggeler in Germany, as well as Peter Hodgson and Howard Kainz in America are notable for their recent contributions to post-USSR thinking about Hegel.

Triads

In previous modern accounts of Hegelianism (to undergraduate classes, for example), especially those formed prior to the Hegel renaissance, Hegel's dialectic was most often characterized as a three-step process, "thesis, antithesis, synthesis"; namely, that a "thesis" (e.g. the French Revolution) would cause the creation of its "antithesis" (e.g. the Reign of Terror that followed), and would eventually result in a "synthesis" (e.g. the constitutional state of free citizens). However, Hegel used this classification only once, and he attributed the terminology to Kant. The terminology was largely developed earlier by Fichte. It was spread by Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus in accounts of Hegelian philosophy, and since then the terms have been used as descriptive of this type of framework.

The "thesis-antithesis-synthesis" approach gives the sense that things or ideas are contradicted or opposed by things that come from outside them. To the contrary, the fundamental notion of Hegel's dialectic is that things or ideas have internal contradictions. From Hegel's point of view, analysis or comprehension of a thing or idea reveals that underneath its apparently simple identity or unity is an underlying inner contradiction. This contradiction leads to the dissolution of the thing or idea in the simple form in which it presented itself and to a higher-level, more complex thing or idea that more adequately incorporates the contradiction. The triadic form that appears in many places in Hegel (e.g. being-nothingness-becoming, immediate-mediate-concrete, abstract-negative-concrete) is about this movement from inner contradiction to higher-level integration or unification.

For Hegel, reason is but "speculative", not "dialectical".[57] Believing that the traditional description of Hegel's philosophy in terms of thesis-antithesis-synthesis was mistaken, a few scholars, like Raya Dunayevskaya, have attempted to discard the triadic approach altogether. According to their argument, although Hegel refers to "the two elemental considerations: first, the idea of freedom as the absolute and final aim; secondly, the means for realising it, i.e. the subjective side of knowledge and will, with its life, movement, and activity" (thesis and antithesis) he doesn't use "synthesis" but instead speaks of the "Whole": "We then recognised the State as the moral Whole and the Reality of Freedom, and consequently as the objective unity of these two elements." Furthermore, in Hegel's language, the "dialectical" aspect or "moment" of thought and reality, by which things or thoughts turn into their opposites or have their inner contradictions brought to the surface, what he called "aufhebung", is only preliminary to the "speculative" (and not "synthesizing") aspect or "moment", which grasps the unity of these opposites or contradiction.

It is widely admitted today[58] that the old-fashioned description of Hegel's philosophy in terms of "thesis-antithesis-synthesis" is inaccurate. Nevertheless, such is the persistence of this misnomer that the model and terminology survive in a number of scholarly works.

Renaissance

In the last half of the 20th century, Hegel's philosophy underwent a major renaissance. This was due to (a) the rediscovery and reevaluation of Hegel as a possible philosophical progenitor of Marxism by philosophically oriented Marxists, (b) a resurgence of the historical perspective that Hegel brought to everything, and (c) an increasing recognition of the importance of his dialectical method. Lukács' History and Class Consciousness (1923) helped to reintroduce Hegel into the Marxist canon. This sparked a renewed interest in Hegel reflected in the work of Herbert Marcuse, Adorno, Ernst Bloch, Dunayevskaya, Alexandre Kojève and Gotthard Günther among others. Marcuse, in Reason and Revolution (1941), made the case for Hegel as a revolutionary and criticized Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse's thesis that Hegel was a totalitarian.[59] The Hegel renaissance also highlighted the significance of Hegel's early works, i.e., those written before the Phenomenology of Spirit. The direct and indirect influence of Kojève's lectures and writings (on the Phenomenology of Spirit, in particular) mean that it is not possible to understand most French philosophers from Jean-Paul Sartre to Jacques Derrida without understanding Hegel.[citation needed] The Swiss theologian Hans Küng has also advanced contemporary scholarship in Hegel studies.

Beginning in the 1960s, Anglo-American Hegel scholarship has attempted to challenge the traditional interpretation of Hegel as offering a metaphysical system: this has also been the approach of Z.A. Pelczynski and Shlomo Avineri. This view, sometimes referred to as the 'non-metaphysical option', has had a decided influence on many major English language studies of Hegel in the past 40 years. U.S. neoconservative political theorist Francis Fukuyama's controversial book The End of History and the Last Man (1992) was heavily influenced by Kojève.[60]

Late 20th-century literature in Western Theology that is friendly to Hegel includes works by such writers as Walter Kaufmann (1966), Dale M. Schlitt (1984), Theodore Geraets (1985), Philip M. Merklinger (1991), Stephen Rocker (1995), and Cyril O'Regan (1995).

Recently, two prominent American philosophers, John McDowell and Robert Brandom (sometimes, half-seriously, referred to as the Pittsburgh Hegelians), have produced philosophical works exhibiting a marked Hegelian influence. Each is avowedly influenced by the late Wilfred Sellars, also of Pittsburgh, who referred to his seminal work, Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind (1956) as a series of "incipient Méditations Hegeliennes" (in homage to Edmund Husserl's 1931 treatise, Meditations Cartesiennes).

Beginning in the 1990s, after the fall of the USSR, a fresh reading of Hegel took place in the West. For these scholars, fairly well represented by the Hegel Society of America and in cooperation with German scholars such as Otto Pöggeler and Walter Jaeschke, Hegel's works should be read without preconceptions. Marx plays a minor role in these new readings, and some contemporary scholars have suggested that Marx's interpretation of Hegel is irrelevant to a proper reading of Hegel. Some American philosophers associated with this movement include Lawrence Stepelevich, Rudolf Siebert, Richard Dien Winfield, and Theodore Geraets.

Criticism

Criticism of Hegel has been widespread in the 19th and the 20th centuries; a diverse range of individuals including Arthur Schopenhauer, Marx, Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertrand Russell, G. E. Moore, Eric Voegelin and A. J. Ayer have challenged Hegelian philosophy from a variety of perspectives. Among the first to take a critical view of Hegel's system was the 19th Century German group known as the Young Hegelians, which included Feuerbach, Marx, Engels, and their followers. In Britain, the Hegelian British Idealism school (members of which included Francis Herbert Bradley, Bernard Bosanquet, and, in the United States, Josiah Royce) was challenged and rejected by analytic philosophers Moore and Russell; Russell, in particular, considered "almost all" of Hegel's doctrines to be false.[61] Regarding Hegel's interpretation of history, Russell commented, "Like other historical theories, it required, if it was to be made plausible, some distortion of facts and considerable ignorance."[62] Logical positivists such as Ayer and the Vienna Circle criticized both Hegelian philosophy and its supporters, such as Bradley.

Hegel's contemporary Schopenhauer was particularly critical, and wrote of Hegel's philosophy as "a pseudo-philosophy paralyzing all mental powers, stifling all real thinking".[63] Kierkegaard criticized Hegel's 'absolute knowledge' unity.[64] Scientist Ludwig Boltzmann also criticized the obscure complexity of Hegel's works, referring to Hegel's writing as an "unclear thoughtless flow of words".[65] In a similar vein, Robert Pippin wrote that Hegel had "the ugliest prose style in the history of the German language".[66] Russell stated in his Unpopular Essays (1950) and A History of Western Philosophy (1945) that Hegel was "the hardest to understand of all the great philosophers". Karl Popper wrote that "there is so much philosophical writing (especially in the Hegelian school) which may justly be criticized as meaningless verbiage".[67]

Popper also makes the claim in the second volume of The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) that Hegel's system formed a thinly veiled justification for the absolute rule of Frederick William III, and that Hegel's idea of the ultimate goal of history was to reach a state approximating that of 1830s Prussia. Popper further proposed that Hegel's philosophy served not only as an inspiration for communist and fascist totalitarian governments of the 20th century, whose dialectics allow for any belief to be construed as rational simply if it could be said to exist. Scholars such as Kaufmann and Shlomo Avineri have criticized Popper's theories about Hegel.[68] Isaiah Berlin listed Hegel as one of the six architects of modern authoritarianism who undermined liberal democracy, along with Rousseau, Claude Adrien Helvétius, Fichte, Saint-Simon, and Joseph de Maistre.[69]

Walter Kaufmann has argued that as unlikely as it may sound, it is not the case that Hegel was unable to write clearly, but that Hegel felt that "he must and should not write in the way in which he was gifted."[70] The only person who saw this clearly and stated it beautifully was Nietzsche according to Kaufmann. Though Nietzsche was not a Hegel scholar, Kaufmann, quotes Nietzsche from the Dawn Esprit and Morality:

"The Germans, who have mastered the secret of being boring with esprit, knowledge and feeling, and who have accustomed themselves to experience boredom as something moral, are afraid of French esprit because it might prick out the eyes of morality - and yet this dread is fused with tempation, as in the bird faced by the rattlesnake. Perhaps none of the famous Germans had more esprit than Hegel; but he also felt such a great German dread of it that this created his peculiar bad style. For the essence of this style is that a core is enveloped, and enveloped once more and again, until it scarcley peeks out, bashful and curious - as 'young women peek out of their veils', to speak with the old woman-hater Aeschylus. But this core is a witty, often saucy idea about the most intellectual matters, a subtle and daring connecting of words, such as belongs in the company of thinkers, as a side dish of science - but in these wrappings it presents itself as abstruse science itself and by all means as supremely moral boredom. Thus the Germans had a form of esprit permitted to them, and they enjoyed it with such extravagant delight that Schopenhauer's good, very good intelligence came to a halt confronted with it: his life long, he blustered against the spectacle the Germans offered him, but he never was able to explain it to himself." [71]

Selected works

Published during Hegel's lifetime

- Life of Jesus

- Differenz des Fichteschen und Schellingschen Systems der Philosophie, 1801

- The Difference Between Fichte's and Schelling's Systems of Philosophy, tr. H. S. Harris and Walter Cerf, 1977

- The German Constitution, 1802

- Phänomenologie des Geistes, 1807

- Phenomenology of Mind, tr. J. B. Baillie, 1910; 2nd ed. 1931

- Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, tr. A. V. Miller, 1977

- Phenomenology of Spirit, translated by Terry Pinkard, 2012

- Wissenschaft der Logik, 1812, 1813, 1816

- Science of Logic, tr. W. H. Johnston and L. G. Struthers, 2 vols., 1929; tr. A. V. Miller, 1969; tr. George di Giovanni, 2010

- Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften, 1817; 2nd ed. 1827; 3rd ed. 1830 (Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences)

- (Pt. I:) The Logic of Hegel, tr. William Wallace, 1874, 2nd ed. 1892; tr. T. F. Geraets, W. A. Suchting and H. S. Harris, 1991; tr. Klaus Brinkmann and Daniel O. Dahlstrom 2010

- (Pt. II:) Hegel's Philosophy of Nature, tr. A. V. Miller, 1970

- (Pt. III:) Hegel's Philosophy of Mind, tr. William Wallace, 1894; rev. by A. V. Miller, 1971

- Elements of the Philosophy of Right, tr. T. M. Knox, 1942; tr. H. B. Nisbet, ed. Allen W. Wood, 1991

Published posthumously

- Lectures on Aesthetics

- Lectures on the Philosophy of History (also translated as Lectures on the Philosophy of World History) 1837

- Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion

- Lectures on the History of Philosophy

Secondary literature

General introductions

- Beiser, Frederick C., 2005. Hegel. New York: Routledge.

- Findlay, J. N., 1958. Hegel: A Re-examination. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-519879-4

- Francke, Kuno, Howard, William Guild, Schiller, Friedrich, 1913-1914 "The German classics of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: masterpieces of German literature translated into English Vol 7, Jay Lowenberg, The Life of Georg Wilhelm Freidrich Hegel". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- Gouin, Jean-Luc, 2000. Hegel ou de la Raison intégrale, suivi de : « Aimer Penser Mourir : Hegel, Nietzsche, Freud en miroirs », Montréal (Québec), Éditions Bellarmin, 225 p. ISBN 2-89007-883-3

- Houlgate, Stephen, 2005. An Introduction to Hegel. Freedom, Truth and History. Oxford: Blackwell

- Kainz, Howard P., 1996. G. W. F. Hegel. Athens: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-1231-0.

- Kaufmann, Walter, 1965. Hegel: A Reinterpretation. New York: Doubleday (reissued Notre Dame IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1978)

- Plant, Raymond, 1983. Hegel: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell

- Singer, Peter, 2001. Hegel: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press (previously issued in the OUP Past Masters series, 1983)

- Scruton, Roger, "Understanding Hegel" in The Philosopher on Dover Beach, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1990. ISBN 0-85635-857-6

- Solomon, Robert, In the Spirit of Hegel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983

- Stern, Robert (2013). The Routledge guide book to Hegel's Phenomenology of spirit (second ed.). Abingdon, Oxon New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415664455.

- Stirling, James Hutchison, The Secret of Hegel: Being the Hegelian System in Origin Principle, Form and Matter, London: Oliver & Boyd

- Taylor, Charles, 1975. Hegel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29199-2.

- Tucker, Robert C., Philosophy and Myth in Karl Marx, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961, chapters 1 ("The Self as God in German Philosophy"), 2 ("History as God's Self-Realization"), and 3 ("The Dialectic of Aggrandizement")

Essays

- Adorno, Theodor W., 1994. Hegel: Three Studies. MIT Press. Translated by Shierry M. Nicholsen, with an introduction by Nicholsen and Jeremy J. Shapiro, ISBN 0-262-51080-4.

- Beiser, Frederick C. (ed.), 1993. The Cambridge Companion to Hegel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38711-6.

- Stewart, Jon, ed., 1996. The Hegel Myths and Legends. Northwestern University Press.

Biography

- Althaus, Horst, 1992. Hegel und die heroischen Jahre der Philosophie. Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag. Eng. tr. Michael Tarsh as Hegel: An Intellectual Biography, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000

- Hondt, Jacques d', 1998. Hegel: Biographie. Calmann-Lévy /// Review (2009) of this biography and of that of Horst Althaus (1999), in the French journal Nuit Blanche : doi:10.1522/030141313 Le Commissaire et le Détective

- Mueller, Gustav Emil, 1968. Hegel: the man, his vision, and work. New York: Pageant Press.

- Pinkard, Terry P., 2000. Hegel: A Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-49679-9.

- Rosenkranz, Karl, 1844. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegels Leben.

Historical

- Löwith, Karl, 1964. From Hegel to Nietzsche: The Revolution in Nineteenth-Century Thought. Translated by David E. Green. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rockmore, Tom, 1993. Before and After Hegel: A Historical Introduction to Hegel's Thought. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220-648-3.

Hegel's development

- Dilthey, Wilhelm, 1906. Die Jugendgeschichte Hegels (repr. in Gesammelte Schriften, 1959, vol. IV)

- Haering, Theodor L., 1929, 1938. Hegel: sein Wollen und sein Werk, 2 vols. Leipzig (repr. Aalen: Scientia Verlag, 1963)

- Harris, H. S., 1972. Hegel's Development: Towards the Sunlight 1770–1801. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Harris, H. S., 1983. Hegel's Development: Night Thoughts (Jena 1801–1806). Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Lukács, Georg, 1948. Der junge Hegel. Zürich and Vienna (2nd ed. Berlin, 1954). Eng. tr. Rodney Livingstone as The Young Hegel, London: Merlin Press, 1975.ISBN 0-262-12070-4

Recent English-language literature

- Forster, Michael N., 1989. Hegel and Skepticism. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-38707-4

- Inwood, Michael, 1983. Hegel. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul (Arguments of the Philosophers)

- Laitinen, Arto & Sandis, Constantine (eds.), 2010. Hegel on Action. Palgrave Macmillan

- Maker, William, 1994. Philosophy Without Foundations: Rethinking Hegel. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-2100-7.

- Pinkard, Terry P., 1988. Hegel's Dialectic: The Explanation of Possibility. Temple University Press

- Pippin, Robert B., 1989. Hegel's Idealism: the Satisfactions of Self-Consciousness. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37923-7.

- Rockmore, Tom, 1986. Hegel's Circular Epistemology. Indiana University Press

- Solomon, Robert C., 1983. In the Spirit of Hegel. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Verene, Donald P., 2007. Hegel's Absolute: An Introduction to Reading the Phenomenology of Spirit. Albany: State University of New York Press

- Westphal, Kenneth, 1989. Hegel's Epistemological Realism. Kluwer Academic Publishers

- Winfield, Richard Dien, 1989. Overcoming Foundations: Studies in Systematic Philosophy. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07008-X.

- Žižek, Slavoj, 2012. Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. London: Verso

Phenomenology of Spirit

- Beiser, Frederick C., ed. 1993. The Cambridge Companion to Hegel. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Braver, Lee. A Thing of This World: a History of Continental Anti-Realism. Northwestern University Press: 2007. ISBN 978-0-8101-2380-9

- Bristow, William, 2007. Hegel and the Transformation of Philosophical Critique. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-929064-4

- Cohen, Joseph, 2007. Le sacrifice de Hegel. (In French language). Paris, Galilée.

- Davis, Walter A., 1989. Inwardness and Existence: Subjectivity in/and Hegel, Heidegger, Marx and Freud. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Doull, James (2000). "Hegel's "Phenomenology" and Postmodern Thought" (PDF). Animus. 5. ISSN 1209-0689. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- Doull, James; Jackson, F.L. (2003). "The Idea of a Phenomenology of Spirit" (PDF). Animus. 8. ISSN 1209-0689. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- Findlay, J. N., 1958. The Philosophy of Hegel: An Introduction and Re-Examination. New York: Collier.

- Harris, H. S., 1995. Hegel: Phenomenology and System. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Hyppolite, Jean, 1946. Genèse et structure de la Phénoménologie de l'esprit. Paris: Aubier. Eng. tr. Samuel Cherniak and John Heckman as Genesis and Structure of Hegel's "Phenomenology of Spirit", Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-8101-0594-2.

- Kalkavage, Peter, 2007. The Logic of Desire: An Introduction to Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. Philadelphia: Paul Dry Books. ISBN 978-1-58988-037-5.

- Kaufmann, Walter, 1966. Hegel: A Reinterpretation, New York: Doubleday Anchor Books (hardcover published 1965).

- Kojève, Alexandre, 1947. Introduction à la lecture de Hegel. Paris: Gallimard. Eng. tr. James H. Nichols, Jr., as Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, Basic Books, 1969. ISBN 0-8014-9203-3

- Pinkard, Terry, 1994. Hegel's Phenomenology: The Sociality of Reason. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Russon, John, 2004. Reading Hegel's Phenomenology. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21692-3.

- Scruton, Roger, "Understanding Hegel" in The Philosopher on Dover Beach, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1990. ISBN 0-85635-857-6

- Solomon, Robert C., 1983. In the Spirit of Hegel. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stace, W. T., 1955. The Philosophy of Hegel. New York: Dover.

- Stern, Robert (2013). The Routledge guide book to Hegel's Phenomenology of spirit (second ed.). Abingdon, Oxon New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415664455.

- Tucker, Robert, 1961. Philosophy and Myth in Karl Marx. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Westphal, Kenneth R., 2003. Hegel's Epistemology: A Philosophical Introduction to the Phenomenology of Spirit. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220-645-9

Logic

- Burbidge, John, 2006. The Logic of Hegel's Logic: An Introduction. Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-633-2

- De Boer, Karin, 2010. On Hegel: The Sway of the Negative. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-230-24754-7

- Hartnack, Justus, 1998. An Introduction to Hegel's Logic. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220-424-3

- Houlgate, Stephen, 2005. The Opening of Hegel's Logic: From Being to Infinity. Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-257-5

- Rinaldi, Giacomo, 1992. A History and Interpretation of the Logic of Hegel Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-9509-6

- Schäfer, Rainer, 2001. Die Dialektik und ihre besonderen Formen in Hegels Logik. Hamburg/Meiner. ISBN 3-7873-1585-3.

- Wallace, Robert M., 2005. Hegel's Philosophy of Reality, Freedom, and God. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84484-3.

- Winfield, Richard Dien, 2006. From Concept to Objectivity: Thinking Through Hegel's Subjective Logic. Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5536-9.jdj

Politics

- Avineri, Shlomo, 1974. Hegel's Theory of the Modern State. Cambridge University Press.

- Brooks, Thom, 2013. Hegel's Political Philosophy: A Systematic Reading of the Philosophy of Right, 2nd edition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Kierans, Kenneth (2008). "'Absolute Negativity': Community and Freedom in Hegel's Philosophy of Right" (PDF). Animus. 12. ISSN 1209-0689. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- Lübbe, Hermann (ed.). Die Hegelsche Rechte. Texte aus den Werken von F. W. Carové, J. E. Erdmann, K. Fischer, E. Gans, H. F. W. Hinrichs, C. L. Michelet, H. B. Oppenheim, K. Rosenkranz und C. Rößler [The Hegelian Right]. Friedrich Frommann Verlag. 1962.

- Marcuse, Herbert, 1941. Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory.

- Moggach, Douglas. 2006. "Introduction: Hegelianism, Republicanism and Modernity", The New Hegelians edited by Douglas Moggach, Cambridge University Press.

- Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies, vol. 2: Hegel and Marx.

- Ritter, Joachim, 1984. Hegel and the French Revolution. MIT Press.

- Riedel, Manfred, 1984. Between Tradition and Revolution: The Hegelian Transformation of Political Philosophy, Cambridge.

- Rose, Gillian, 1981. Hegel Contra Sociology. Athlone Press. ISBN 0-485-12036-4.

- Scruton, Roger, "Hegel as a conservative thinker" in The Philosopher on Dover Beach, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1990. ISBN 0-85635-857-6

Aesthetics

- Bungay, Stephen, 1987. Beauty and Truth. A Study of Hegel's Aesthetics. New York.

- Danto, Arthur Coleman, 1986. The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art. Columbia University Press.

- Desmond, William, 1986. Art and the Absolute. Albany (New York).

- Gethmann-Siefert, Annemarie, Einführung in Hegel's Ästhetik, Wilhelm Fink (German).

- Mark Jarzombek, "The Cunning of Architecture's Reason," Footprint (#1, Autumn 2007), pp. 31–46.

- Maker, William (ed.), 2000. Hegel and Aesthetics. New York.

- Olivier, Alain P., 2003. Hegel et la Musique. Paris (French).

- Roche, Mark-William, 1998. Tragedy and Comedy. A Systematic Study and a Critique of Hegel. Albany. New York.

- Winfield, Richard Dien, 1996. Stylistics. Rethinking the Artforms after G. W. Hegel. Albany, Suny Press.

Religion

- Cohen, Joseph, 2005. Le spectre juif de Hegel (in French language); Preface by Jean-Luc Nancy. Paris, Galilée.

- Desmond, William, 2003. Hegel's God: A Counterfeit Double?. Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-0565-5

- Dickey, Laurence (1987). Hegel: Religion, Economics, and the Politics of Spirit, 1770–1807. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521389129.

- Fackenheim, E. The Religious Dimension in Hegel's Thought. University of Chicago Press. 0226233502.

- Lewis, Thomas A. (2011). Religion, Modernity, and Politics in Hegel. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959559-4.

- O'Regan, Cyril, 1994. The Heterodox Hegel. State University of New York Press, Albany. ISBN 0-7914-2006-X.

- Rocker, Stephen, 1995. Hegel's Rational Religion: The Validity of Hegel's Argument for the Identity in Content of Absolute Religion and Absolute Philosophy. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Andrew Shanks, Hegel and Religious Faith: Divided brain, atoning spirit (London, T & T Clark, 2011).

See also

Notes

- ^ Butler, Judith, Subjects of desire: Hegelian reflections in twentieth-century France (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987)

- ^ "One of the few things on which the analysts, pragmatists, and existentialists agree with the dialectical theologians is that Hegel is to be repudiated: their attitude toward Kant, Aristotle, Plato, and the other great philosophers is not at all unanimous even within each movement; but opposition to Hegel is part of the platform of all four, and of the Marxists, too." Walter Kaufmann, "The Hegel Myth and Its Method", in From Shakespeare to Existentialism: Studies in Poetry, Religion, and Philosophy by Walter Kaufmann, Beacon Press, Boston 1959, page 88-119

- ^ "Why did Hegel not become for the Protestant world something similar to what Thomas Aquinas was for Roman Catholicism?" Karl Barth, Protestant Thought From Rousseau To Ritschl: Being The Translation Of Eleven Chapters Of Die Protestantische Theologie Im 19. Jahrhundert, 268 Harper, 1959

- ^ Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Sense and Nonsense. p. 63. trans. Herbert L. and Patricia Allen Dreyfus (Northwestern Univ. Press) 1964

- ^ Andrew Bowie, Schelling and Modern European Philosophy 2 Routledge London, 1993

- ^ Pinkard, Hegel: A Biography, pp. 2-3; p. 745.

- ^ Ibid., 3, incorrectly gives the date as September 20, 1781, and describes Hegel as aged eleven. Cf. the index to Pinkard's book and his "Chronology of Hegel's Life", which correctly give the date as 1783 (pp. 773, 745); see also German Wikipedia.

- ^ Ibid., 4.

- ^ http://assets.cambridge.org/052149/6799/sample/0521496799WSN01.pdf

- ^ Ibid., 80.

- ^ http://www3.documenta.de/research/assets/Uploads/Hegel-Fragment-on-Love.pdf

- ^ http://www.sunypress.edu/pdf/60921.pdf

- ^ Ibid., 223.

- ^ Ibid., 224-5.

- ^ Ibid., 228.

- ^ Ibid., 192.

- ^ Ibid., 238.

- ^ Ibid., 337.

- ^ Ibid., 354-5.

- ^ Ibid., 356.

- ^ Ibid., 658-9.

- ^ Norman Davies, Europe: A history p. 687

- ^ Pinkard, Hegel: A Biography, p. 548.

- ^ par. 378

- ^ See Science of Logic, trans. Miller [Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities, 1989], pp. 133-136 and 138, top

- ^ Ibid., 111

- ^ Ibid., 145

- ^ See Ibid., 146, top

- ^ Steven Schroeder (2000). Between Freedom and Necessity: An Essay on the Place of Value. Rodopi. p. 104. ISBN 978-90-420-1302-5. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Stefan Gruner: "Hegel's Aether Doctrine", VDM Publ., 2010, ISBN 978-3-639-28451-5

- ^ Etext of Philosophy of Right Hegel, 1827 (translated by Dyde, 1897)

- ^ Pelczynski, A.Z.; 1984; 'The Significane of Hegel's speration of the state and civil society' pp1-13 in Pelczynski, A.Z. (ed.); 1984; The State and Civil Society; Cambridge University Press

- ^ a b Zaleski, Pawel (2008). "Tocqueville on Civilian Society. A Romantic Vision of the Dichotomic Structure of Social Reality". Archiv für Begriffsgeschichte. 50. Felix Meiner Verlag.

- ^ ibid

- ^ Hegel, G. W. F. "Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie". pp. 336–337. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ Hartnack, Justus (1998). An Introduction to Hegel's Logic. Hackett Publishing. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-87220-424-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Hartnack quotes Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy Volume I.- ^ Hegel, G. W. F. "Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie". pp. 319–343. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ Copleston, Frederick Charles (2003). A History of Philosophy: Volume 7: 18th and 19th century German philosophy. Continuum International Publishing Group. Chapter X. ISBN 0-8264-6901-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help)- ^ The notable Introduction to Philosophy of History expresses the historical aspects of the dialectic.

- ^ "[T]he task that touches the interest of philosophy most nearly at the present moment: to put God back at the peak of philosophy, absolutely prior to all else as the one and only ground of everything." (Hegel, "How the Ordinary Human Understanding Takes Philosophy as displayed in the works of Mr. Krug," Kritisches Journal der Philosophie, I, no. 1, 1802, pages 91-115)

- ^ Walter Kaufmann, Hegel: Reinterpretation, Texts, and Commentary, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1965, p.276-77

- ^ Ibid.,p. 277

- ^ Kaufmann, p.277

- ^ A CRITIQUE OF KAUFMANN'S HEGEL, BY STEPHEN D. CRITES

- ^ Kaufmann, p. 292

- ^ Kaufmann, Discovery of the Mind: Goethe, Kant and Hegelp.203

- ^ Kaufmann, Discovery of the Mind: Goethe, Kant and Hegel,1980, McGraw Hill Company, p.203

- ^ J E Walker (1991). Thought and faith in the philosophy of Hegel. Springer. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-7923-1234-5. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Kaufmann, Hegel: A Reinterpretation, Anchor, p.115

- ^ Ibid., p.116

- ^ Faust cited in Kaufmann, Hegel: A Reinterpretation, Anchor Books, p.118

- ^ Faust>Till as they are, at last I, too, am shattered.

- ^ Kaufmann, p.119

- ^ Kaufmann, p.119

- ^ Karl Löwith, From Hegel to Nietzsche: The Revolution in Nineteenth-Century Thought, translated by David E. Green, New York: Columbia University Press, 1964.

- ^ Benedetto Croce, Guide to Aesthetics, Translated by Patrick Romanell, "Translator's Introduction", The Library of Liberal Arts, The Bobbs–Merrill Co., Inc., 1965

- ^ Hegel and Language edited by Jere O'Neill Surber. Pg. 238.

- ^ Žižek, Slavoj. "The Return to Hegel". Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- ^ Robinson, Paul (1990). The Freudian Left: Wilhelm Reich, Geza Roheim, Herbert Marcuse. Cornell University Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-87220-424-3.

- ^ Williams, Howard; David Sullivan; Gwynn Matthews (1997). Francis Fukuyama and the End of History. University of Wales Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0-7083-1428-7.

- ^ B.Russell, History of western philosophy, pg 701 chapter 22, paragraph 1.

- ^ Russell, 735.

- ^ On the Basis of Morality.

- ^ Søren Kierkegaard Concluding Unscientific Postscriptt

- ^ Ludwig Boltzmann, Theoretical physics and philosophical problems: Selected writings, p. 155, D. Reidel, 1974, ISBN 90-277-0250-0

- ^ Robert B. Pippin, Hegel's Idealism: The Satisfaction of Self-Consciousness (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 5

- ^ Karl Popper, Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (New York: Routledge, 1963), 94.

- ^ See for instance Walter Kaufmann 1959, The Hegel Myth and Its Method

- ^ Berlin, Isaiah, Freedom and Betrayal: Six Enemies of Human Liberty (Princeton University Press, 2003)

- ^ Kaufmann, 1966, Hegel: A Reinterpretation, p.99

- ^ Nietzsche, Dawn,p.193

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel/.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)- Hegel page in 'The History Guide'

- Hegel.net - freely available resources (under the GNU FDL)

- « Der Instinkt der Vernünftigkeit » and other texts - Works on Hegel in Université du Québec site (in French)

- Template:Worldcat id

- Lowenberg J., (1913) "The Life of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel". in German classics of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. New York: German Publication Society.

- Hegel, as the National Philosopher of Germany (1874) Karl Rosenkranz, Granville Stanley Hall, William Torrey Harris, Gray, Baker & Co. 1874

Audio

Video

- Hegel: The First Cultural Psychologist 2007 from Vimeo Andy Blunden

Societies

Hegel's texts online