This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

The 1996 FIA Formula One World Championship was the 50th season of FIA Formula One motor racing. The championship commenced on 10 March and ended on 13 October after sixteen races.[1][2][3] Two World Championship titles were awarded, one for Drivers and one for Constructors.

Damon Hill won the Drivers' Championship two years after being beaten by a point by Michael Schumacher, making him the first son of a World Champion (his father Graham having won the title in 1962 and 1968) to have won the title himself as well as the only until Nico Rosberg, son of 1982 champion Keke Rosberg, won the title 34 years later in 2016.[4][5][6] Hill, who had finished runner-up for the past two seasons, was seriously threatened only by his teammate, newcomer Jacques Villeneuve, the 1995 IndyCar and Indianapolis 500 champion.[7][8] Williams-Renault easily won the Constructors' title, as there was no other competitor strong enough to post a consistent challenge throughout the championship.[3][9] This was also the beginning of the end of Williams's 1990s dominance, as it was announced that Hill and designer Adrian Newey would depart at the conclusion of the season, with engine manufacturer Renault also leaving after 1997.[8][10][11]

Two-time defending world champion Michael Schumacher had moved to Ferrari and despite numerous reliability problems, they had gradually developed into a front-running team by the end of the season.[12] Defending Constructors' Champion Benetton began their decline towards the middle of the grid, having lost key personnel due to Schumacher's departure, and failed to win a race.[13][14] Olivier Panis took the only victory of his career at the Monaco Grand Prix.[15]

This was the last championship for a British driver until Lewis Hamilton in 2008.

Teams and drivers

editThe numbering system used since 1974 was dropped.[16][17] Ferrari was given the numbers 1 and 2 after hiring the defending champion Michael Schumacher, despite finishing the previous year's Constructors' Championship in third, Benetton received numbers 3 and 4 for winning the Constructors' Championship, Williams got numbers 5 and 6 for finishing second, McLaren got 7 and 8 for finishing fourth, Ligier got 9 and 10 for finishing fifth, and so on, with the number 13 being skipped.[18][19]

The following teams and drivers competed in the 1996 FIA Formula One World Championship. All teams competed with tyres supplied by Goodyear.

Team changes

edit- By receiving an Italian licence the defending Constructors' Champion Benetton officially became an Italian constructor, though it continued to operate from the same base in Britain.[23]

- Jordan gained a new title sponsor in British cigarette brand Benson & Hedges, who joined oil supplier Total and engine company Peugeot in the team's official name.[24]

- Meanwhile, Tyrrell lost their title sponsor, Finnish communications company Nokia, becoming officially known simply as Tyrrell Yamaha.[25]

- Forti also lost the sponsorship of Italian dairy corporation Parmalat, as well as any official connection to Ford, although they continued to use Ford engines.[citation needed]

- Scuderia Italia decided to end their two-year working relationship with Minardi, so the team once again became known simply as Minardi Team.[citation needed]

- Two teams disappeared from the entry list entirely. Larrousse had missed the early races of 1995 before finally announcing their withdrawal before the San Marino Grand Prix. Gérard Larrousse claimed several times the team would reappear in 1996, but a combination of legal and financial difficulties meant this never materialised. Pacific withdrew from the sport at the end of 1995.[26][27]

- Scuderia Ferrari decided to change from the V12 engine they competed with the previous season to the V-10 engine configuration which was used by most of the other teams. For the first time since 1988, no Formula One entrants utilized a V12 engine in their car.

Driver changes

edit- Defending double world champion Michael Schumacher left Benetton to join Ferrari, citing the need for a new challenge.[28] He displaced Jean Alesi, who moved in the opposite direction.[28] Gerhard Berger was offered the chance to stay as Schumacher's teammate, but eventually opted to join Alesi at Benetton.[29] Ferrari filled the seat with Jordan's Eddie Irvine.[30]

- Berger's decision to join Benetton ousted Johnny Herbert, who joined Sauber alongside Heinz-Harald Frentzen.[29][31] Sauber's other seat had been filled in 1995 by both Karl Wendlinger, who left F1 still struggling to recover fully from injuries sustained at the 1994 Monaco Grand Prix, and Jean-Christophe Boullion, who returned to his testing role at Williams.[32]

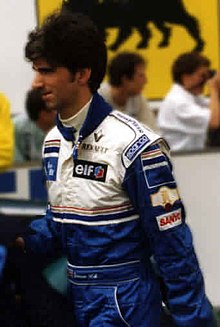

- Williams dropped David Coulthard, instead recruiting Canadian rookie Jacques Villeneuve, who had won the 1995 CART Championship, to partner Damon Hill.[8] Coulthard joined McLaren alongside Mika Häkkinen, replacing Mark Blundell, who moved into CART with PacWest Racing.[33]

- Martin Brundle left Ligier in order to replace the Ferrari-bound Irvine at Jordan, where he would partner Rubens Barrichello.[34] Ligier replaced him by bringing in Forti's Pedro Diniz alongside Olivier Panis.[35][36] Aguri Suzuki, who had shared Brundle's seat in 1995, left F1 altogether.[37]

- Footwork had an entirely new line-up in 1996, dispensing with all three of their 1995 drivers.[38] Gianni Morbidelli became a test driver for Jordan, before returning to a race seat in 1997 with Sauber, while fellow Italian Max Papis moved to America to race in the CART Series.[39][40] Taki Inoue was rumoured to have secured a drive with both Tyrrell and Minardi, but ultimately lost out on both seats and moved to sports cars. Footwork replaced them with Jos Verstappen from the now-defunct Simtek team, and 1995 International Formula 3000 runner-up Ricardo Rosset.[41][42] Simtek's other driver, Domenico Schiattarella left F1 completely.[43]

- Luca Badoer moved from Minardi to Forti, replacing Pedro Diniz, who had gone to Ligier.[44][45] As his replacement, Minardi brought in Giancarlo Fisichella, who had been racing with Alfa Romeo in the International Touring Car Championship, to partner Pedro Lamy.[46] Badoer's teammate at Forti would be Andrea Montermini, who had raced for the now-extinct Pacific team in 1995.[47][48] He replaced Roberto Moreno, who moved into Champ Car.[47][49]

- Tyrrell was the only team on the grid to have an unchanged driver line-up from 1995 with Ukyo Katayama and Mika Salo.[50]

Mid-season changes

edit- Due to his commitments with Alfa Romeo in the International Touring Car Championship, Giancarlo Fisichella missed several races for Minardi. European Formula 3000 driver Tarso Marques raced at the Brazilian and Argentine Grands Prix, while Giovanni Lavaggi, who had raced for Pacific in 1995, replaced the pair of them from the German Grand Prix onwards due to his superior financial backing.[51][52]

- Forti were declared bankrupt after the British Grand Prix, leaving both their drivers out of a drive.[53] Luca Badoer would eventually return to F1 in 1999 with Minardi, after a spell in the FIA GT Championship, while Andrea Montermini became a test driver for the short-lived Lola team in 1997.[54][55]

Calendar

editThe 1996 FIA Formula One World Championship comprised the following races:

Calendar changes

edit- The Australian Grand Prix was moved from the Adelaide Street Circuit to the Albert Park Circuit in Port Phillip near Melbourne. The change of venue also resulted in the grand prix becoming the season opener instead of its finale.

- The Indonesian Grand Prix (renamed from the Pacific Grand Prix) was due to be held in Indonesia at the Sentul International Circuit as the final round but the race did not make the calendar as the corners were unsuitable for Formula One cars.

Regulation changes

editTechnical regulations

edit- In 1995, the sides of the cockpit were raised in order to provide better head protection for the driver. These sides were raised even higher (to mid-helmet height) for 1996, along with a wraparound head restraint made of foam to prevent head injuries such as those suffered by Mika Häkkinen during qualifying for the 1995 Australian Grand Prix.[56][57] Also, the cockpit opening was made larger, with the front tip now extending to 625 mm (24.6 in) from the front wheel centre line instead of 750 mm (30 in).[58][59]

- Needle-like nosecone designs with a sharp point, such as the McLaren MP4/10, Forti FG01 and Tyrrell 023, were also banned in favour of more blunt nose sections.[60]

- The minimum weight (with driver) was raised from 595 kg (1,312 lb) to 600 kg (1,300 lb).[61]

- To prevent damage to other cars' tyres, front wing endplates had to be at least 10 mm (0.39 in) thick.[58]

Sporting and event regulations

edit- The race weekend schedule was changed for the 1996 season compared to 1995. The number of free practice sessions was increased from the two to three with the number of laps allocated for each day increased from 23 to 30. Also, to increase the spectacle, the Friday qualifying session was dropped, with the FIA World Motor Sport Council opting to have only one qualifying session, held on Saturday afternoon.[57][62]

- This year saw the introduction of the "107% rule", which meant all cars had to be within 107% of the pole position time in order to qualify for the race.[57][60]

- The previous system of having a red and green light to start the race was replaced by the current system of five red lights turning on sequentially with a period of usually five seconds, then all going out simultaneously before starting the race.[56][59][60]

- A new numbering system for cars was adopted for 1996 and remained in place until the end of 2013, when a new system was introduced. Previously, the reigning Drivers' Champion's team had simply swapped car numbers with the previous Drivers' Champion's team to carry numbers 1 and 2, with all other teams retaining their existing numbers. For 1996 the reigning Drivers' Champion was given number 1 and his teammate number 2 with the rest of the teams numbered in the order of their finishing position in the previous year's Constructors' Championship. Any new teams were allocated the following numbers.

- Continued safety improvements and modifications on circuits brought the number of "high risk" corners on the calendar down to two.[56][59]

Season report

editDamon Hill won the season opener in Australia from his Williams teammate Jacques Villeneuve, with Ferrari's Eddie Irvine finishing third.[63] Villeneuve was leading but late on in the race the team found out that Villeneuve had an oil leak and ordered him to swap places with teammate Hill.[64]

The Brazilian Grand Prix took place in heavy rain, and was won from pole position by Damon Hill, with Jean Alesi second in a Benetton and Michael Schumacher third in a Ferrari.

Despite suffering a bout of food poisoning, Damon Hill made it three wins out of three at the Argentine Grand Prix, with Jacques Villeneuve helping Williams to their second one-two of the season. Jos Verstappen scored his only point of the season, while Andrea Montermini registered his only finish of the season. Pedro Diniz was involved in two major incidents during the race. First he collided with Luca Badoer, whose Forti was flipped and landed upside down in the gravel, forcing the marshals to bring out the safety car. Diniz managed to continue and made a pit stop as the safety car was preparing to pull in, only to retire when he came back onto the circuit and his Ligier burst into flames because a safety-valve in the fuel tank had jammed open.

The European Grand Prix at the Nürburgring[b] in Germany was won by Jacques Villeneuve for his first F1 victory in only his fourth race. Michael Schumacher finished second, with David Coulthard third in a McLaren, just ahead of Hill.

The San Marino Grand Prix was won by Damon Hill after starting from second position. Michael Schumacher again finished second, despite his front-right brake seizing halfway around the final lap, while Gerhard Berger was third, driving for the Benetton team. Jacques Villeneuve retired near the end of the race after being hit by Jean Alesi.

Round six at Monaco was run in wet weather, causing significant attrition and setting a record for the fewest cars (three) to be running at the end of a Grand Prix. Olivier Panis scored what would be his sole career Formula One victory, earning the last Formula One victory for the Ligier team, and the first ever for engine manufacturer Mugen Motorsports, after he made the switch onto slick tyres in a well-timed pitstop. David Coulthard was second, nearly five seconds behind Panis. Johnny Herbert scored his only points of the season, finishing third in a Sauber, more than half a minute behind Coulthard.

The Spanish Grand Prix saw Michael Schumacher's first Ferrari victory, and is generally regarded as one of the German's finest races. In torrential rain, he produced a stunning drive, helping him to earn the nickname "the Rainmaster". Schumacher recovered from a poor start to take the lead from Villeneuve on lap 13, and from then on he dominated the race, frequently lapping over three seconds faster than the remainder of the field. Jean Alesi finished second, more than 45 seconds behind the winner, with Jacques Villeneuve third. Rubens Barrichello, who was running in second place after Jacques Villeneuve and Alesi made their pit stops, put in a strong performance in this race, but was forced to retire due to a clutch problem with 20 laps remaining. After an uneventful race on his part, Heinz-Harald Frentzen finished in fourth, while Mika Häkkinen took fifth after surviving a spin off the track in the closing stages of the race. Jos Verstappen, running fifth after the retirements of Barrichello and Berger, crashed into the tyre barrier with 12 laps left, guaranteeing Diniz his first Formula One point as by this time only six drivers were left in the race. Damon Hill had started the race from pole position, but dropped to 8th after spinning twice in the opening laps, before another spin into the pit wall on lap 12 ended his race.

The Canadian Grand Prix was won from pole position by Damon Hill, with home driver Jacques Villeneuve second, and Frenchman Jean Alesi third.

The second half of the season began with the French Grand Prix at Magny-Cours. Michael Schumacher qualified in pole position but his engine blew on the warm-up lap and he did not start. The race was won by Damon Hill, with Jacques Villeneuve finishing second in the other Williams, and Jean Alesi again third for the Benetton team. This was the last Grand Prix where a Forti car started the race (two weeks later the team would fail to qualify for the British Grand Prix, the final Formula One event they would enter), however both cars were forced to retire.

Jacques Villeneuve took his second win of the season at the British Grand Prix, with Benetton's Gerhard Berger second and McLaren's Mika Häkkinen coming home third for his first podium since his near-fatal crash at the 1995 Australian Grand Prix. Jordan's Rubens Barrichello took fourth, equalling his best finish of the season. The final points went to David Coulthard in the second McLaren and Martin Brundle in the second Jordan. Hill took pole position for his home race, but made a slow start and retired shortly before half distance, after a wheel nut problem caused him to spin off at Copse Corner while he was trying to pass Häkkinen. For the third consecutive race, Ferrari drivers Michael Schumacher and Eddie Irvine were both forced to retire with technical issues.

The German Grand Prix at Hockenheim was won by Damon Hill, taking his seventh victory of the season after he started from pole position. Austrian driver Gerhard Berger started alongside Hill on the front row in his Benetton and led for much of the race, until his engine failed with three laps remaining. Berger's teammate Jean Alesi was second and Jacques Villeneuve was third. The win meant Hill extended his lead over Villeneuve in the Drivers' Championship to 21 points with five races remaining.

The Hungarian Grand Prix was won by Jacques Villeneuve after starting from third position. Villeneuve's teammate Damon Hill finished second, with Jean Alesi third. This was Williams's fifth 1–2 finish of the season, and it secured their fourth Constructors' Championship in five years.

The Belgian Grand Prix saw Michael Schumacher take victory, driving a Ferrari. Schumacher had crashed heavily in Friday practice, but recovered to qualify third before taking his second win of the season. Jacques Villeneuve, who had started from pole position, finished second in his Williams, with Mika Häkkinen third in a McLaren. Drivers' Championship leader, Damon Hill, finished fifth.

The Italian Grand Prix was won by Michael Schumacher, giving Ferrari their first victory at Monza since 1988. Jean Alesi finished second in a Benetton, with Mika Häkkinen third. Damon Hill took pole position and led until he made an error and spun off on lap 6, while his teammate and main championship rival, Jacques Villeneuve, could only manage seventh.

The penultimate race of the season was the Portuguese Grand Prix. Williams's Jacques Villeneuve won from teammate Damon Hill in second and Ferrari's Michael Schumacher in third. This victory, Villeneuve's fourth of the season, ensured that the Drivers' Championship battle between him and Hill would go to the final round. Benetton's Jean Alesi finished fourth, just behind Schumacher, while Eddie Irvine in the second Ferrari and Gerhard Berger in the second Benetton survived a last-lap collision to take fifth and sixth respectively.

The 1996 season concluded with the title-deciding Japanese Grand Prix on 13 October. Before the event, Hill was leading the Drivers' Championship standings, with teammate Villeneuve needing to win the race without Hill scoring in order to win the championship himself. In qualifying, Villeneuve took pole position, but made a poor start to the race and later retired when a wheel fell off his car. The race was won by Damon Hill for his eighth victory of the season, securing the Drivers' Championship in the process. Michael Schumacher finished second in a Ferrari, enabling the Italian team to steal second place in the Constructors' Championship from Benetton, with Mika Häkkinen finishing third in a McLaren. Hill became the first son of a World Champion to win the championship himself, his father Graham having twice been champion, in 1962 and 1968.

Results and standings

editGrands Prix

editPoints scoring system

editPoints are awarded to the top six classified finishers in each race for the drivers and constructors championships.[66]

| Position | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Points | 10 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

World Drivers' Championship standings

edit

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

- † – Driver did not finish the Grand Prix but was classified, as he completed more than 90% of the race distance.

World Constructors' Championship standings

edit

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

- † – Driver did not finish the Grand Prix but was classified, as he completed more than 90% of the race distance.

Non-championship event results

editThe 1996 season also included a single event which did not count towards the World Championship, the Formula One Indoor Trophy at the Bologna Motor Show. This is to date the final competitive non-championship event in Formula One history, as the event would cater to Formula 3000 machinery from 1997 onwards.

| Race name | Venue | Date | Winning driver | Constructor | Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula One Indoor Trophy | Bologna Motor Show | 7–8 December | Giancarlo Fisichella | Benetton | Report |

Notes

edit- ^ Forti Grand Prix were declared bankrupt after the British Grand Prix and took no further part in the championship.[20]

- ^ All Formula One Grands Prix held at the Nürburgring since 1984 have used the 5 km (3.1 mi) long GP-Strecke and not the 21 km (13 mi) long Nordschleife, which was last used by Formula One in 1976.

- ^ Michael Schumacher set the fastest time in qualifying, but did not start the race due to an engine failure on the formation lap. Pole position was left vacant on the grid. Damon Hill, in the second slot, was the first driver on the grid. Schumacher is still considered to have held pole position.

References

edit- ^ "1996 RACE RESULTS". Formula 1® - The Official F1® Website. Archived from the original on 17 September 2024. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ a b "The 1996 F1 calendar". www.grandprix.com. 18 December 1995. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d "1996 • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ a b FIA Formula One World Championship – Drivers points, www.fia.com, as archived at web.archive.org

- ^ "1994 • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Like father, like son - the second-generation F1 racers". Formula1.com. 19 January 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Damon HILL • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Widdows, Rob (May 2009). "Damon Hill on Jacques Villeneuve: Williams team-mates". Motor Sport Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 April 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ a b FIA Formula One World Championship – Constructors points, www.fia.com, as archived at web.archive.org

- ^ GMM (28 February 2012). "Williams admits mistake to let Newey go". Motorsport.com. Motorsport Network. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Keith, Collantine (28 April 2010). "The rise and fall of Williams". www.racefans.net. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Weeks, Jim (18 February 2016). "Schumacher and Ferrari: The Launch of F1's Greatest Partnership". Vice. Vice Media. Archived from the original on 19 September 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Admin (31 July 2018). "Working Within Benetton During the 1990s". UNRACEDF1.COM. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Benetton • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com (in French). Archived from the original on 10 September 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Olivier PANIS - Wins • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Beer, Matt (28 November 2013). "Insight: Formula 1's iconic numbers". www.autosport.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Judkins, Ollie (12 November 2010). "Numbers Nostalgia". F1 Colours. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ a b "1996 FIA Formula One World Championship Entry List" (PDF). FIA.com. Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 4 December 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2005. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "1995 • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Gallery: F1 teams that became defunct in the last 25 years". www.motorsport.com. 4 April 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Models in 1996 • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "All the drivers 1996 • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Benetton to race under Italian colours". New Straits Times. 29 November 1995. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Jordan to be sponsored by Benson and Hedges". www.motorsport.com. 8 May 1996. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Tyrrell loses Nokia". grandprix.com. 18 December 1995. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Larrousse's last months as F1 Team". UNRACEDF1.COM. 28 July 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "The untold story of Pacific Grand Prix in the F1". UNRACEDF1.COM. 19 November 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Schumacher signs for Ferrari". www.motorsport.com. 8 May 1995. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Berger signs for Benetton". grandprix.com. 4 September 1995. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Irvine to partner Schumacher at Ferrari". The Independent. 27 September 1995. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Herbert signs for Sauber". The Independent. 19 December 1995. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Karl Wendlinger signed by Sauber". www.motorsport.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "BBC - A Sporting Nation - David Coulthard's best season 2001". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ La-Croix.com (30 September 1995). "FORMULE 1 L'Irlandais Martin Brundle, qui pilote cette saison une Ligier, rejoindra en 1996 le Brésilien Rubens Barrichello au volant d'une Jordan-Peugeot". La Croix (in French). Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Pedro Diniz | Motor Sport Magazine Database". Motor Sport Magazine. 12 June 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Ligier - Seasons • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Aguri SUZUKI • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Footwork - Seasons • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Gianni MORBIDELLI - Involvement • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Max PAPIS • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com (in French). Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Thorn, Dan (7 February 2017). "6 Races Which Show Jos Verstappen Was Pretty Awesome Too". WTF1. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Ricardo ROSSET - Grands Prix started • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Domenico SCHIATTARELLA • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com (in French). Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Luca BADOER - Seasons • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Pedro DINIZ - Seasons • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Minardi - Seasons • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Forti - Seasons • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Andrea MONTERMINI - Seasons • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Roberto MORENO • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com (in French). Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Tyrrell - Seasons • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "ForzaMinardi.com - Giancarlo Fisichella". www.forzaminardi.com. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Giancarlo Fisichella: Dreams do come true". www.motorsport.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Forti • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com (in French). Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "Luca BADOER - Involvement • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Collins, Aaron (6 September 2018). "F1: The Disastrous Story of MasterCard Lola". essaar.co.uk. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "Safety Improvements in F1 since 1963". AtlasF1. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "The new rules for 1996". GrandPrix.com. 4 March 1996. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b "1996-1998 technical regulations changes". Motorsport.com. 8 May 1996. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b c Steven de Groote (1 January 2009). "F1 rules and stats 1990-1999". F1Technical. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "New Regulations for 1996". F1 Formula 1 96: A Champion and a Gentleman!. Duke Video. 1996. Event occurs at time 5:47–6:49.

- ^ Tanaka, Hiromasa. Transition of Regulation and Technology in Formula One. Honda R&D Technical Review 2009 - F1 Special (The Third Era Activities), 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1995). Autocourse 1995–96. Hazelton Publishing. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-874557-36-4.

- ^ "Australia 1996 - Result • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Reiman, Samuel (10 March 2015). "Race of firsts: Remembering the 1996 Australian GP". FOX Sports. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "Formula One Results 1996". Motorsport Stats. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ a b Jones, Bruce (1997). "Review of the 1996 Season – Final Tables". The Official ITV Formula One 1997 Grand Prix Guide. London, England: Carlton Books. pp. 30–31. ISBN 1-85868-319-X – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hallberry, Andy, ed. (1997). Autosport 1996 Grand Prix Review. Teddington, Middlesex: Haymarket Specialist Publications Ltd. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-86024-936-8 – via Internet Archive.

External links

edit- formula1.com – 1996 official driver standings (archived)

- formula1.com – 1996 official team standings (archived)