Amyntas II (Ancient Greek: Ἀμύντας), also known as Amyntas "the Little", was king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon for several months around 394/3 BC. He became king in July or August of 394/3 after the death of Aeropus II, but he was soon after assassinated by an Elimieotan nobleman named Derdas and succeeded by Aeropus' son Pausanias.[4]

| Amyntas II | |

|---|---|

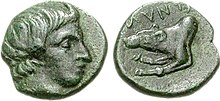

Bronze of Amyntas II. The male deity on the obverse is unidentified, but the wolf on the reverse is taken from the coins of Argos, the alleged origin of the Argead kings. His name is spelt [A]MYNT[A].[1] | |

| King of Macedonia | |

| Reign | July/August – August/September 394/3[2] |

| Predecessor | Aeropus II |

| Successor | Pausanias |

| Born | ? |

| Died | August/September 394/3 BC |

| Spouse | daughter of Archelaus (name unknown)[3] |

| Issue | Disputed: Ptolemy of Aloros |

| Dynasty | Argead dynasty |

| Father | Disputed: Menelaus, son of Alexander I Archelaus |

| Mother | unknown |

| Religion | Ancient Greek religion |

He was likely the son of Menelaus, second son of Alexander I, but he could have also been the son of Archelaus. The most influential view, advanced by Historian Nicholas Hammond, is that Archelaus married his younger daughter to Amyntas or Amyntas' son in order to stave off a future power struggle with the line of Menelaus.[5][6][7] The argument is based in part on a line from Aelian's Varia Historia about an Amyntas being Menelaus' son.[8] The alternative theory holds that the polygamous Archelaus married his son (Amyntas) to his daughter to cement the branch lines: a half-brother and a half-sister.[9]

Ptolemy of Aloros, future regent for Perdiccas III, was possibly the son of Amyntas and Archelaus' daughter, whose name is unknown. Diodorus simply refers to Ptolemy as a "son of Amyntas," which Hammond argued must mean Amyntas II because all other sons of Amyntas III are accounted for.[10][11][12] However, the relevant text is almost universally regarded as corrupt and might actually say “Ptolemy the Alorite fraudulently murdered the son of Amyntas, Alexander.”[13]

When listing the kings of Macedonia, Diodorus omits Amyntas' reign, but all other ancient sources, as well as modern scholars, agree that he ruled before Pausanias.[14][15][6]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Oliver D. Hoover, Handbook of Coins of Macedon and Its Neighbors. Part I: Macedon, Illyria, and Epeiros, Sixth to First Centuries BC [The Handbook of Greek Coinage Series, Volume 3], Lancaster/London, Classical Numismatic Group, 2016, p.295

- ^ March, Duane (1995). "The Kings of Makedon: 399-369 B.C". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte: 280.

- ^ Hammond, N.G.L. (1979). A History of Macedonia Volume II: 550-336 B.C. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 169.

- ^ Borza, Eugene (1990). In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence of Macedon. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-691-05549-1

- ^ Hammond 1979, p. 169.

- ^ a b Roisman, Joseph (2010). "Classical Macedonia to Perdiccas III". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 158.

- ^ Carney, Elizabeth (2000). Women and Monarchy in Macedonia. University of Oklahoma Press, p.250. ISBN 0-8061-3212-4

- ^ Claudius Aelianus. "Various History". Claudius Aelianus His Various History. Book XII. Translated by Stanley, Thomas (1665), 12.43.

- ^ Fox, Robin Lane (2011). "399–369 BC". In Fox, Robin Lane (ed.). Brill’s Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon, 650 BC–300 AD. Boston: Brill. pp. 216–217.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus. "Library". Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes. Vol. 4–8. Translated by Oldfather, C.H. Harvard University Press, 15.71.1.

- ^ Hammond 1979, p. 182.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 162.

- ^ Fox 2011, p. 232.

- ^ Diodorus, "Library", 14.84.6.

- ^ March 1995, p. 275.

|}