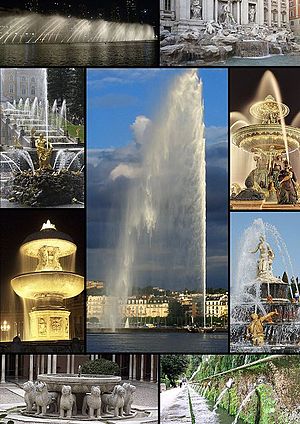

A fountain, from the Latin "fons" (genitive "fontis"), meaning source or spring, is a decorative reservoir used for discharging water. It is also a structure that jets water into the air for a decorative or dramatic effect.

Fountains were originally purely functional, connected to springs or aqueducts and used to provide drinking water and water for bathing and washing to the residents of cities, towns and villages. Until the late 19th century most fountains operated by gravity, and needed a source of water higher than the fountain, such as a reservoir or aqueduct, to make the water flow or jet into the air.

In addition to providing drinking water, fountains were used for decoration and to celebrate their builders. Roman fountains were decorated with bronze or stone masks of animals or heroes. In the Middle Ages, Moorish and Muslim garden designers used fountains to create miniature versions of the gardens of paradise. King Louis XIV of France used fountains in the Gardens of Versailles to illustrate his power over nature. The baroque decorative fountains of Rome in the 17th and 18th centuries marked the arrival point of restored Roman aqueducts and glorified the Popes who built them.[1]

By the end of the 19th century, as indoor plumbing became the main source of drinking water, urban fountains became purely decorative. Mechanical pumps replaced gravity and allowed fountains to recycle water and to force it high into the air. The Jet d'Eau in Lake Geneva, built in 1951, shoots water 140 metres (460 ft) in the air. The highest such fountain in the world is King Fahd's Fountain in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, which spouts water 260 metres (850 ft) above the Red Sea.[2]

Fountains are used today to decorate city parks and squares; to honor individuals or events; for recreation and for entertainment. A splash pad or spray pool allows city residents to enter, get wet and cool off in summer. The musical fountain combines moving jets of water, colored lights and recorded music, controlled by a computer, for dramatic effects. Fountains can themselves also be musical instruments played by obstruction of one or more of their water jets. Drinking fountains provide clean drinking water in public buildings, parks and public spaces.

History

editAncient fountains

editAncient civilizations built stone basins to capture and hold precious drinking water. A carved stone basin, dating to around 700 BC, was discovered in the ruins of the ancient Sumerian city of Lagash in modern Iraq. The ancient Assyrians constructed a series of basins in the gorge of the Comel River, carved in solid rock, connected by small channels, descending to a stream. The lowest basin was decorated with carved reliefs of two lions.[3] The ancient Egyptians had ingenious systems for hoisting water up from the Nile for drinking and irrigation, but without a higher source of water it was not possible to make water flow by gravity, There are lion-shaped fountains in the Temple of Dendera in Qena.

The ancient Greeks used aqueducts and gravity-powered fountains to distribute water. According to ancient historians, fountains existed in Athens, Corinth, and other ancient Greek cities in the 6th century BC as the terminating points of aqueducts which brought water from springs and rivers into the cities. In the 6th century BC, the Athenian ruler Peisistratos built the main fountain of Athens, the Enneacrounos, in the Agora, or main square. It had nine large cannons, or spouts, which supplied drinking water to local residents.[4]

Greek fountains were made of stone or marble, with water flowing through bronze pipes and emerging from the mouth of a sculpted mask that represented the head of a lion or the muzzle of an animal. Most Greek fountains flowed by simple gravity, but they also discovered how to use principle of a siphon to make water spout, as seen in pictures on Greek vases.[5]

Ancient Roman fountains

editThe Ancient Romans built an extensive system of aqueducts from mountain rivers and lakes to provide water for the fountains and baths of Rome. The Roman engineers used lead pipes instead of bronze to distribute the water throughout the city. The excavations at Pompeii, which revealed the city as it was when it was destroyed by Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, uncovered free-standing fountains and basins placed at intervals along city streets, fed by siphoning water upwards from lead pipes under the street. The excavations of Pompeii also showed that the homes of wealthy Romans often had a small fountain in the atrium, or interior courtyard, with water coming from the city water supply and spouting into a small bowl or basin.

Ancient Rome was a city of fountains. According to Sextus Julius Frontinus, the Roman consul who was named curator aquarum or guardian of the water of Rome in 98 AD, Rome had nine aqueducts which fed 39 monumental fountains and 591 public basins, not counting the water supplied to the Imperial household, baths and owners of private villas. Each of the major fountains was connected to two different aqueducts, in case one was shut down for service.[6]

The Romans were able to make fountains jet water into the air, by using the pressure of water flowing from a distant and higher source of water to create hydraulic head, or force. Illustrations of fountains in gardens spouting water are found on wall paintings in Rome from the 1st century BC, and in the villas of Pompeii.[7] The Villa of Hadrian in Tivoli featured a large swimming basin with jets of water. Pliny the Younger described the banquet room of a Roman villa where a fountain began to jet water when visitors sat on a marble seat. The water flowed into a basin, where the courses of a banquet were served in floating dishes shaped like boats.[8]

Roman engineers built aqueducts and fountains throughout the Roman Empire. Examples can be found today in the ruins of Roman towns in Vaison-la-Romaine and Glanum in France, in Augst, Switzerland, and other sites.

Medieval fountains

editIn Nepal there were public drinking fountains at least as early as 550 AD. They are called dhunge dharas or hitis. They consist of intricately carved stone spouts through which water flows uninterrupted from underground water sources. They are found extensively in Nepal and some of them are still operational. Construction of water conduits like hitis and dug wells are considered as pious acts in Nepal.[9]

During the Middle Ages, Roman aqueducts were wrecked or fell into decay, and many fountains throughout Europe stopped working, so fountains existed mainly in art and literature, or in secluded monasteries or palace gardens. Fountains in the Middle Ages were associated with the source of life, purity, wisdom, innocence, and the Garden of Eden.[10] In illuminated manuscripts like the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1411–1416), the Garden of Eden was shown with a graceful gothic fountain in the center (see illustration). The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck, finished in 1432, also shows a fountain as a feature of the adoration of the mystic lamb, a scene apparently set in Paradise.

The cloister of a monastery was supposed to be a replica of the Garden of Eden, protected from the outside world. Simple fountains, called lavabos, were placed inside Medieval monasteries such as Le Thoronet Abbey in Provence and were used for ritual washing before religious services.[11]

Fountains were also found in the enclosed medieval jardins d'amour, "gardens of courtly love" – ornamental gardens used for courtship and relaxation. The medieval romance The Roman de la Rose describes a fountain in the center of an enclosed garden, feeding small streams bordered by flowers and fresh herbs.

Some Medieval fountains, like the cathedrals of their time, illustrated biblical stories, local history and the virtues of their time. The Fontana Maggiore in Perugia, dedicated in 1278, is decorated with stone carvings representing prophets and saints, allegories of the arts, labors of the months, the signs of the zodiac, and scenes from Genesis and Roman history.[12]

Medieval fountains could also provide amusement. The gardens of the Counts of Artois at the Château de Hesdin, built in 1295, contained famous fountains, called Les Merveilles de Hesdin ("The Wonders of Hesdin") which could be triggered to drench surprised visitors.[13]

Fountains of the Islamic world

editShortly after the spread of Islam, the Arabs incorporated into their city planning the famous Islamic gardens. Islamic gardens after the 7th century were traditionally enclosed by walls and were designed to represent paradise. The paradise gardens, were laid out in the form of a cross, with four channels representing the rivers of Paradise, dividing the four parts of the world.[14] Water sometimes spouted from a fountain in the center of the cross, representing the spring or fountain, Salsabil, described in the Qur'an as the source of the rivers of Paradise.[15]

In the 9th century, the Banū Mūsā brothers, a trio of Persian Inventors, were commissioned by the Caliph of Baghdad to summarize the engineering knowledge of the ancient Greek and Roman world. They wrote a book entitled the Book of Ingenious Devices, describing the works of the 1st century Greek Engineer Hero of Alexandria and other engineers, plus many of their own inventions. They described fountains which formed water into different shapes and a wind-powered water pump,[16] but it is not known if any of their fountains were ever actually built.[17]

The Persian rulers of the Middle Ages had elaborate water distribution systems and fountains in their palaces and gardens. Water was carried by a pipe into the palace from a source at a higher elevation. Once inside the palace or garden it came up through a small hole in a marble or stone ornament and poured into a basin or garden channels. The gardens of Pasargades had a system of canals which flowed from basin to basin, both watering the garden and making a pleasant sound. The Persian engineers also used the principle of the syphon (called shotor-gelu in Persian, literally 'neck of the camel) to create fountains which spouted water or made it resemble a bubbling spring. The garden of Fin, near Kashan, used 171 spouts connected to pipes to create a fountain called the Howz-e jush, or "boiling basin".[18]

The 11th century Persian poet Azraqi described a Persian fountain:

- From a marvelous faucet of gold pours a wave

- whose clarity is more pure than a soul;

- The turquoise and silver form ribbons in the basin

- coming from this faucet of gold ...[19]

Reciprocating motion was first described in 1206 by Arab Muslim engineer and inventor al-Jazari when the kings of the Artuqid dynasty in Turkey commissioned him to manufacture a machine to raise water for their palaces. The finest result was a machine called the double-acting reciprocating piston pump, which translated rotary motion to reciprocating motion via the crankshaft-connecting rod mechanism.[20]

The palaces of Moorish Spain, particularly the Alhambra in Granada, had famous fountains. The patio of the Sultan in the gardens of Generalife in Granada (1319) featured spouts of water pouring into a basin, with channels which irrigated orange and myrtle trees. The garden was modified over the centuries – the jets of water which cross the canal today were added in the 19th century.[21]

The fountain in the Court of the Lions of the Alhambra, built from 1362 to 1391, is a large vasque mounted on twelve stone statues of lions. Water spouts upward in the vasque and pours from the mouths of the lions, filling four channels dividing the courtyard into quadrants.[22] The basin dates to the 14th century, but the lions spouting water are believed to be older, dating to the 11th century.[23]

The design of the Islamic garden spread throughout the Islamic world, from Moorish Spain to the Mughal Empire in the Indian subcontinent. The Shalimar Gardens built by Emperor Shah Jahan in 1641, were said to be ornamented with 410 fountains, which fed into a large basin, canal and marble pools.

In the Ottoman Empire, rulers often built fountains next to mosques so worshippers could do their ritual washing. Examples include the Fountain of Qasim Pasha (1527), Temple Mount, Jerusalem, an ablution and drinking fountain built during the Ottoman reign of Suleiman the Magnificent; the Fountain of Ahmed III (1728) at the Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, another Fountain of Ahmed III in Üsküdar (1729) and Tophane Fountain (1732). Palaces themselves often had small decorated fountains, which provided drinking water, cooled the air, and made a pleasant splashing sound. One surviving example is the Fountain of Tears (1764) at the Bakhchisarai Palace, in Crimea; which was made famous by a poem of Alexander Pushkin. The sebil was a decorated fountain that was often the only source of water for the surrounding neighborhood. It was often commissioned as an act of Islamic piety by a rich person.

Renaissance fountains (15th–17th centuries)

editIn the 14th century, Italian humanist scholars began to rediscover and translate forgotten Roman texts on architecture by Vitruvius, on hydraulics by Hero of Alexandria, and descriptions of Roman gardens and fountains by Pliny the Younger, Pliny the Elder, and Varro. The treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria, by Leon Battista Alberti, which described in detail Roman villas, gardens and fountains, became the guidebook for Renaissance builders.[24]

In Rome, Pope Nicholas V (1397–1455), himself a scholar who commissioned hundreds of translations of ancient Greek classics into Latin, decided to embellish the city and make it a worthy capital of the Christian world. In 1453, he began to rebuild the Acqua Vergine, the ruined Roman aqueduct which had brought clean drinking water to the city from eight miles (13 km) away. He also decided to revive the Roman custom of marking the arrival point of an aqueduct with a mostra, a grand commemorative fountain. He commissioned the architect Leon Battista Alberti to build a wall fountain where the Trevi Fountain is now located. The aqueduct he restored, with modifications and extensions, eventually supplied water to the Trevi Fountain and the famous baroque fountains in the Piazza del Popolo and Piazza Navona.[25]

One of the first new fountains to be built in Rome during the Renaissance was the fountain in the piazza in front of the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere (1472), which was placed on the site of an earlier Roman fountain. Its design, based on an earlier Roman model, with a circular vasque on a pedestal pouring water into a basin below, became the model for many other fountains in Rome, and eventually for fountains in other cities, from Paris to London.[26]

In 1503, Pope Julius II decided to recreate a classical pleasure garden in the same place. The new garden, called the Cortile del Belvedere, was designed by Donato Bramante. The garden was decorated with the Pope's famous collection of classical statues, and with fountains. The Venetian Ambassador wrote in 1523, "... On one side of the garden is a most beautiful loggia, at one end of which is a lovely fountain that irrigates the orange trees and the rest of the garden by a little canal in the center of the loggia ...[27] The original garden was split in two by the construction of the Vatican Library in the 16th century, but a new fountain by Carlo Maderno was built in the Cortile del Belvedere, with a jet of water shooting up from a circular stone bowl on an octagonal pedestal in a large basin.[28]

In 1537, in Florence, Cosimo I de' Medici, who had become ruler of the city at the age of only 17, also decided to launch a program of aqueduct and fountain building. The city had previously gotten all its drinking water from wells and reservoirs of rain water, which meant that there was little water or water pressure to run fountains. Cosimo built an aqueduct large enough for the first continually-running fountain in Florence, the Fountain of Neptune in the Piazza della Signoria (1560–1567). This fountain featured an enormous white marble statue of Neptune, resembling Cosimo, by sculptor Bartolomeo Ammannati.[29]

Under the Medicis, fountains were not just sources of water, but advertisements of the power and benevolence of the city's rulers. They became central elements not only of city squares, but of the new Italian Renaissance garden. The great Medici Villa at Castello, built for Cosimo by Benedetto Varchi, featured two monumental fountains on its central axis; one showing with two bronze figures representing Hercules slaying Antaeus, symbolizing the victory of Cosimo over his enemies; and a second fountain, in the middle of a circular labyrinth of cypresses, laurel, myrtle and roses, had a bronze statue by Giambologna which showed the goddess Venus wringing her hair. The planet Venus was governed by Capricorn, which was the emblem of Cosimo; the fountain symbolized that he was the absolute master of Florence.[30]

By the middle Renaissance, fountains had become a form of theater, with cascades and jets of water coming from marble statues of animals and mythological figures. The most famous fountains of this kind were found in the Villa d'Este (1550–1572), at Tivoli near Rome, which featured a hillside of basins, fountains and jets of water, as well as a fountain which produced music by pouring water into a chamber, forcing air into a series of flute-like pipes. The gardens also featured giochi d'acqua, water jokes, hidden fountains which suddenly soaked visitors.[31] Between 1546 and 1549, the merchants of Paris built the first Renaissance-style fountain in Paris, the Fontaine des Innocents, to commemorate the ceremonial entry of the King into the city. The fountain, which originally stood against the wall of the church of the Holy Innocents, as rebuilt several times and now stands in a square near Les Halles. It is the oldest fountain in Paris.[32]

Henry constructed an Italian-style garden with a fountain shooting a vertical jet of water for his favorite mistress, Diane de Poitiers, next to the Château de Chenonceau (1556–1559). At the royal Château de Fontainebleau, he built another fountain with a bronze statue of Diane, goddess of the hunt, modeled after Diane de Poitiers.[33]

Later, after the death of Henry II, his widow, Catherine de Medici, expelled Diane de Poitiers from Chenonceau and built her own fountain and garden there.

King Henry IV of France made an important contribution to French fountains by inviting an Italian hydraulic engineer, Tommaso Francini, who had worked on the fountains of the villa at Pratalino, to make fountains in France. Francini became a French citizen in 1600, built the Medici Fountain, and during the rule of the young King Louis XIII, he was raised to the position of Intendant général des Eaux et Fontaines of the king, a position which was hereditary. His descendants became the royal fountain designers for Louis XIII and for Louis XIV at Versailles.[34]

In 1630, another Medici, Marie de Medici, the widow of Henry IV, built her own monumental fountain in Paris, the Medici Fountain, in the garden of the Palais du Luxembourg. That fountain still exists today, with a long basin of water and statues added in 1866.[35]

Baroque fountains (17th–18th century)

editBaroque Fountains of Rome

editThe 17th and 18th centuries were a golden age for fountains in Rome, which began with the reconstruction of ruined Roman aqueducts and the construction by the Popes of mostra, or display fountains, to mark their termini. The new fountains were expressions of the new Baroque art, which was officially promoted by the Catholic Church as a way to win popular support against the Protestant Reformation; the Council of Trent had declared in the 16th century that the Church should counter austere Protestantism with art that was lavish, animated and emotional. The fountains of Rome, like the paintings of Rubens, were examples of the principles of Baroque art. They were crowded with allegorical figures, and filled with emotion and movement. In these fountains, sculpture became the principal element, and the water was used simply to animate and decorate the sculptures. They, like baroque gardens, were "a visual representation of confidence and power."[31]

The first of the Fountains of St. Peter's Square, by Carlo Maderno, (1614) was one of the earliest Baroque fountains in Rome, made to complement the lavish Baroque façade he designed for St. Peter's Basilica behind it. It was fed by water from the Paola aqueduct, restored in 1612, whose source was 266 feet (81 m) above sea level, which meant it could shoot water twenty feet up from the fountain. Its form, with a large circular vasque on a pedestal pouring water into a basin and an inverted vasque above it spouting water, was imitated two centuries later in the Fountains of the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

The Triton Fountain in the Piazza Barberini (1642), by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, is a masterpiece of Baroque sculpture, representing Triton, half-man and half-fish, blowing his horn to calm the waters, following a text by the Roman poet Ovid in the Metamorphoses. The Triton fountain benefited from its location in a valley, and the fact that it was fed by the Aqua Felice aqueduct, restored in 1587, which arrived in Rome at an elevation of 194 feet (59 m) above sea level (fasl), a difference of 130 feet (40 m) in elevation between the source and the fountain, which meant that the water from this fountain jetted sixteen feet straight up into the air from the conch shell of the triton.[36]

The Piazza Navona became a grand theater of water, with three fountains, built in a line on the site of the Stadium of Domitian. The fountains at either end are by Giacomo della Porta; the Neptune fountain to the north, (1572) shows the God of the Sea spearing an octopus, surrounded by tritons, sea horses and mermaids. At the southern end is Il Moro, possibly also a figure of Neptune riding a fish in a conch shell. In the center is the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, (The Fountain of the Four Rivers) (1648–51), a highly theatrical fountain by Bernini, with statues representing rivers from the four continents; the Nile, Danube, Plate River and Ganges. Over the whole structure is a 54-foot (16 m) Egyptian obelisk, crowned by a cross with the emblem of the Pamphili family, representing Pope Innocent X, whose family palace was on the piazza. The theme of a fountain with statues symbolizing great rivers was later used in the Place de la Concorde (1836–40) and in the Fountain of Neptune in the Alexanderplatz in Berlin (1891). The fountains of Piazza Navona had one drawback - their water came from the Acqua Vergine, which had only a 23-foot (7.0 m) drop from the source to the fountains, which meant the water could only fall or trickle downwards, not jet very high upwards.[37]

The Trevi Fountain is the largest and most spectacular of Rome's fountains, designed to glorify the three different Popes who created it. It was built beginning in 1730 at the terminus of the reconstructed Acqua Vergine aqueduct, on the site of Renaissance fountain by Leon Battista Alberti. It was the work of architect Nicola Salvi and the successive project of Pope Clement XII, Pope Benedict XIV and Pope Clement XIII, whose emblems and inscriptions are carried on the attic story, entablature and central niche. The central figure is Oceanus, the personification of all the seas and oceans, in an oyster-shell chariot, surrounded by Tritons and Sea Nymphs.

In fact, the fountain had very little water pressure, because the source of water was, like the source for the Piazza Navona fountains, the Acqua Vergine, with a 23-foot (7.0 m) drop. Salvi compensated for this problem by sinking the fountain down into the ground, and by carefully designing the cascade so that the water churned and tumbled, to add movement and drama.[38] Wrote historians Maria Ann Conelli and Marilyn Symmes, "On many levels the Trevi altered the appearance, function and intent of fountains and was a watershed for future designs."[39]

-

Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi by Bernini, (1648–51)

-

Fontana della Barcaccia, (1627)

-

Fountains of St. Peter's Square by Carlo Maderno (1614) and Bernini (1677)

-

Triton Fountain by Bernini, (1642)

-

Fontana delle Api (Fountains of the Bees) (1644)

Baroque fountains of Versailles

editBeginning in 1662, King Louis XIV of France began to build a new kind of garden, the Garden à la française, or French formal garden, at the Palace of Versailles. In this garden, the fountain played a central role. He used fountains to demonstrate the power of man over nature, and to illustrate the grandeur of his rule. In the Gardens of Versailles, instead of falling naturally into a basin, water was shot into the sky, or formed into the shape of a fan or bouquet. Dancing water was combined with music and fireworks to form a grand spectacle. These fountains were the work of the descendants of Tommaso Francini, the Italian hydraulic engineer who had come to France during the time of Henry IV and built the Medici Fountain and the Fountain of Diana at Fontainebleau.

Two fountains were the centerpieces of the Gardens of Versailles, both taken from the myths about Apollo, the sun god, the emblem of Louis XIV, and both symbolizing his power. The Fontaine Latone (1668–70) designed by André Le Nôtre and sculpted by Gaspard and Balthazar Marsy, represents the story of how the peasants of Lycia tormented Latona and her children, Diana and Apollo, and were punished by being turned into frogs. This was a reminder of how French peasants had abused Louis's mother, Anne of Austria, during the uprising called the Fronde in the 1650s. When the fountain is turned on, sprays of water pour down on the peasants, who are frenzied as they are transformed into creatures.[38][40]

The other centerpiece of the Gardens, at the intersection of the main axes of the Gardens of Versailles, is the Bassin d'Apollon (1668–71), designed by Charles Le Brun and sculpted by Jean Baptiste Tuby. This statue shows a theme also depicted in the painted decoration in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles: Apollo in his chariot about to rise from the water, announced by Tritons with seashell trumpets. Historians Mary Anne Conelli and Marilyn Symmes wrote, "Designed for dramatic effect and to flatter the king, the fountain is oriented so that the Sun God rises from the west and travels east toward the chateau, in contradiction to nature."[38]

Besides these two monumental fountains, the Gardens over the years contained dozens of other fountains, including thirty-nine animal fountains in the labyrinth depicting the fables of Jean de La Fontaine.

There were so many fountains at Versailles that it was impossible to have them all running at once; when Louis XIV made his promenades, his fountain-tenders turned on the fountains ahead of him and turned off those behind him. Louis built an enormous pumping station, the Machine de Marly, with fourteen water wheels and 253 pumps to raise the water three hundred feet from the River Seine, and even attempted to divert the River Eure to provide water for his fountains, but the water supply was never enough.[41]

Baroque fountains of Peterhof

editIn Russia, Peter the Great founded a new capital at St. Petersburg in 1703 and built a small Summer Palace and gardens there beside the Neva River. The gardens featured a fountain of two sea monsters spouting water, among the earliest fountains in Russia.

In 1709, he began constructing a larger palace, Peterhof Palace, alongside the Gulf of Finland, Peter visited France in 1717 and saw the gardens and fountains of Louis XIV at Versailles, Marly and Fontainebleau. When he returned he began building a vast Garden à la française with fountains at Peterhof. The central feature of the garden was a water cascade, modeled after the cascade at the Château de Marly of Louis XIV, built in 1684. The gardens included trick fountains designed to drench unsuspecting visitors, a popular feature of the Italian Renaissance garden.,[42]

In 1800–1802 the Emperor Paul I of Russia and his successor, Alexander I of Russia, built a new fountain at the foot of the cascade depicting Samson prying open the mouth of a lion, representing Peter's victory over Sweden in the Great Northern War in 1721. The fountains were fed by reservoirs in the upper garden, while the Samson fountain was fed by a specially-constructed aqueduct four kilometers in length.

-

Samson and the Lion fountain at Peterhof Palace, Russia (1800–1802)

-

Sea Canal

-

Roman Fountains (1763–80)

-

Danaida Fountain

19th century fountains

edit-

Fontaine du Palmier, Paris (1809)

-

Fountain in Trafalgar Square, (1845)

In the early 19th century, London and Paris built aqueducts and new fountains to supply clean drinking water to their exploding populations. Napoleon Bonaparte started construction on the first canals bringing drinking water to Paris, fifteen new fountains, the most famous being the Fontaine du Palmier in the Place du Châtelet, (1896–1808), celebrating his military victories.

He also restored and put back into service some of the city's oldest fountains, such as the Medici Fountain. Two of Napoleon's fountains, the Chateau d'Eau and the fountain in the Place des Vosges, were the first purely decorative fountains in Paris, without water taps for drinking water.[43]

Louis-Philippe (1830–1848) continued Napoleon's work, and added some of Paris's most famous fountains, notably the Fontaines de la Concorde (1836–1840) and the fountains in the Place des Vosges.[44]

Following a deadly cholera epidemic in 1849, Louis Napoleon decided to completely rebuild the Paris water supply system, separating the water supply for fountains from the water supply for drinking. The most famous fountain built by Louis Napoleon was the Fontaine Saint-Michel, part of his grand reconstruction of Paris boulevards. Louis Napoleon relocated and rebuilt several earlier fountains, such as the Medici Fountain and the Fontaine de Leda, when their original sites were destroyed by his construction projects.[45]

In the mid-nineteenth century the first fountains were built in the United States, connected to the first aqueducts bringing drinking water from outside the city. The first fountain in Philadelphia, at Centre Square, opened in 1809, and featured a statue by sculptor William Rush. The first fountain in New York City, in City Hall Park, opened in 1842, and the first fountain in Boston was turned on in 1848. The first famous American decorative fountain was the Bethesda Fountain in Central Park in New York City, opened in 1873.[46]

The 19th century also saw the introduction of new materials in fountain construction; cast iron (the Fontaines de la Concorde); glass (the Crystal Fountain in London (1851)) and even aluminium (the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain in Piccadilly Circus, London, (1897)).[47]

The invention of steam pumps meant that water could be supplied directly to homes, and pumped upward from fountains. The new fountains in Trafalgar Square (1845) used steam pumps from an artesian well. By the end of the 19th century fountains in big cities were no longer used to supply drinking water, and were simply a form of art and urban decoration.[47]

Another fountain innovation of the 19th century was the illuminated fountain: The Bartholdi Fountain at the Philadelphia Exposition of 1876 was illuminated by gas lamps. In 1884 a fountain in Britain featured electric lights shining upward through the water. The Exposition Universelle (1889) which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution featured a fountain illuminated by electric lights shining up though the columns of water. The fountains, located in a basin forty meters in diameter, were given color by plates of colored glass inserted over the lamps. The Fountain of Progress gave its show three times each evening, for twenty minutes, with a series of different colors.[48]

20th century fountains

edit-

The "Pont d'eau' from the 1931 Paris Colonial Exhibit, created a "bridge" of water forty meters long and six meters wide.

-

Buckingham Fountain in Chicago (1933)

-

Fountain of Prometheus at the Rockefeller Center in New York City (1933)

-

The battery of water cannons at the Palais de Chaillot at the World Expo in Paris (1937). The water cannons still function.

-

Stravinsky Fountain, next to the Pompidou Center, Paris (1983)

-

Fontaine de la Pyramide, Cour Napoléon of the Louvre, (1988)

-

Fontaine Cristaux, Homage to Béla Bartok, Jean-Yves Lechevallier, Paris, (1980)

Paris fountains in the 20th century no longer had to supply drinking water - they were purely decorative; and, since their water usually came from the river and not from the city aqueducts, their water was no longer drinkable. Twenty-eight new fountains were built in Paris between 1900 and 1940; nine new fountains between 1900 and 1910; four between 1920 and 1930; and fifteen between 1930 and 1940.[49]

The biggest fountains of the period were those built for the International Expositions of 1900, 1925 and 1937, and for the Colonial Exposition of 1931. Of those, only the fountains from the 1937 exposition at the Palais de Chaillot still exist. (See Fountains of International Expositions).

Only a handful of fountains were built in Paris between 1940 and 1980. The most important ones built during that period were on the edges of the city, on the west, just outside the city limits, at La Défense, and to the east at the Bois de Vincennes.

Between 1981 and 1995, during the terms of President François Mitterrand and Culture Minister Jack Lang, and of Mitterrand's bitter political rival, Paris Mayor Jacques Chirac (Mayor from 1977 until 1995), the city experienced a program of monumental fountain building that exceeded that of Napoleon Bonaparte or Louis Philippe. More than one hundred fountains were built in Paris in the 1980s, mostly in the neighborhoods outside the center of Paris, where there had been few fountains before These included the Fontaine Cristaux, homage to Béla Bartók by Jean-Yves Lechevallier (1980); the Stravinsky Fountain next to the Pompidou Center, by sculptors Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely (1983); the fountain of the Pyramid of the Louvre by I.M. Pei, (1989), the Buren Fountain by sculptor Daniel Buren, Les Sphérades fountain, both in the Palais-Royal, and the fountains of Parc André-Citroën. The Mitterrand-Chirac fountains had no single style or theme. Many of the fountains were designed by famous sculptors or architects, such as Jean Tinguely, I.M. Pei, Claes Oldenburg and Daniel Buren, who had radically different ideas of what a fountain should be. Some were solemn, and others were whimsical. Most made little effort to blend with their surroundings - they were designed to attract attention.

Fountains built in the United States between 1900 and 1950 mostly followed European models and classical styles. The Samuel Francis Dupont Memorial Fountain was designed and created by Henry Bacon and Daniel Chester French, the architect and sculptor of the Lincoln Memorial, in 1921, in a pure neoclassical style.

Buckingham Fountain in Chicago was one of the first American fountains to use powerful modern pumps to shoot water as high as 150 feet (46 meters) into the air. The Fountain of Prometheus, built at the Rockefeller Center in 1933, was the first American fountain in the Art-Deco style.

After World War II, fountains in the United States became more varied in form. Some, like Ruth Asawa's Andrea (1968)[50] and Vaillancourt Fountain (1971), both located in San Francisco, were pure works of sculpture. Other fountains, like the Frankin Roosevelt Memorial Waterfall (1997), by architect Lawrence Halprin, were designed as landscapes to illustrate themes. This fountain is part of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington D.C., which has four outdoor "rooms" illustrating his presidency. Each "room" contains a cascade or waterfall; the cascade in the third room illustrates the turbulence of the years of the World War II. Halprin wrote at an early stage of the design; "the whole environment of the memorial becomes sculpture: to touch, feel, hear and contact - with all the senses."[51]

The end of the 20th century the development of high-shooting fountains, beginning with the Jet d'eau in Geneva in 1951, and followed by taller and taller fountains in the United States and the Middle East. The highest fountain today is King Fahd's Fountain in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

It also saw the increasing popularity of the musical fountain, which combined water, music and light, choreographed by computers. (See Musical fountain below).

Contemporary fountains (2001–present)

editThe fountain called 'Bit.Fall' by German artist Julius Popp (2005) uses digital technologies to spell out words with water. The fountain is run by a statistical program which selects words at random from news stories on the Internet. It then recodes these words into pictures. Then 320 nozzles inject the water into electromagnetic valves. The program uses rasterization and bitmap technologies to synchronize the valves so drops of water form an image of the words as they fall. According to Popp, the sheet of water is "a metaphor for the constant flow of information from which we cannot escape."[52]

Crown Fountain is an interactive fountain and video sculpture feature in Chicago's Millennium Park. Designed by Catalan artist Jaume Plensa, it opened in July 2004.[53][54] The fountain is composed of a black granite reflecting pool placed between a pair of glass brick towers. The towers are 50 feet (15 m) tall,[53] and they use light-emitting diodes (LEDs) to display digital videos on their inward faces. Construction and design of Crown Fountain cost US$17 million.[55] Weather permitting, the water operates from May to October,[56] intermittently cascading down the two towers and spouting through a nozzle on each tower's front face.

Few new fountains have been built in Paris since 2000. The most notable is La Danse de la fontaine emergente (2008), located on Place Augusta-Holmes, rue Paul Klee, in the 13th arrondissement. It was designed by the French-Chinese sculptor Chen Zhen (1955-2000), shortly before his death in 2000, and finished through the efforts of his spouse and collaborator. It shows a dragon, in stainless steel, glass and plastic, emerging and submerging from the pavement of the square. The fountain is in three parts. A bas-relief of the dragon is fixed on the wall of the structure of the water-supply plant, and the dragon seems to be emerging from the wall and plunging underground. This part of the dragon is opaque. The second and third parts depict the arch of the dragon's back coming out of the pavement. These parts of the dragon are transparent, and water under pressure flows visibly within, and is illuminated at night.

Musical fountains

editMusical fountains create a theatrical spectacle with music, light and water, usually employing a variety of programmable spouts and water jets controlled by a computer.

Musical fountains were first described in the 1st century AD by the Greek scientist and engineer Hero of Alexandria in his book Pneumatics. Hero described and provided drawings of "A bird made to whistle by flowing water," "A Trumpet sounded by flowing water," and "Birds made to sing and be silent alternately by flowing water." In Hero's descriptions, water pushed air through musical instruments to make sounds. It is not known if Hero made working models of any of his designs.[57]

During the Italian Renaissance, the most famous musical fountains were located in the gardens of the Villa d'Este, in Tivoli. which were created between 1550 and 1572. Following the ideas of Hero of Alexandria, the Fountain of the Owl used a series of bronze pipes like flutes to make the sound of birds. The most famous feature of the garden was the great Organ Fountain. It was described by the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne, who visited the garden in 1580: "The music of the Organ Fountain is true music, naturally created ... made by water which falls with great violence into a cave, rounded and vaulted, and agitates the air, which is forced to exit through the pipes of an organ. Other water, passing through a wheel, strikes in a certain order the keyboard of the organ. The organ also imitates the sound of trumpets, the sound of cannon, and the sound of muskets, made by the sudden fall of water ...[58] The Organ Fountain fell into ruins, but it was recently restored and plays music again.

Louis XIV created the idea of the modern musical fountain by staging spectacles in the Gardens of Versailles, using music and fireworks to accompany the flow of the fountains.

The great international expositions held in Philadelphia, London and Paris featured the ancestors of the modern musical fountain. They introduced the first fountains illuminated by gas lights (Philadelphia in 1876); and the first fountains illuminated by electric lights (London in 1884 and Paris in 1889).[59] The Exposition Universelle (1900) in Paris featured fountains illuminated by colored lights controlled by a keyboard.[60] The Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931 presented the Théâtre d'eau, or water theater, located in a lake, with performance of dancing water. The Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (1937) had combined arches and columns of water from fountains in the Seine with light, and with music from loudspeakers on eleven rafts anchored in the river, playing the music of the leading composers of the time. (See International Exposition Fountains, above.)

Today some of the best-known musical fountains in the world are at the Bellagio Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, (2009); the Dubai Fountain in the United Arab Emirates; the World of Color at Disney California Adventure Park (2010) and Aquanura at the Efteling in the Netherlands (2012).[citation needed]

-

The Organ Fountain at the Villa d'Este, Tivoli (1550–1572)

-

The Château d'eau and plaza of the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900. The fountains were illuminated with different colors at night.

-

The musical fountain of the Bellagio Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, with pivoting nozzles to vary the patterns of the water, controlled by computers and accompanied by music (1998)

-

Dubai Fountain in the United Arab Emirates (2009) can shoot water 150 meters in the air, or present computer-choreographed water dancing to music

-

Multimedia Fountain Roshen is the only one in Ukraine and the largest floating fountain in Europe, built in the river Southern Buh in Vinnytsia City near Festivalny Isle (Kempa Isle)[61]

-

Multimedia Fountain Kangwon Land is considered Asia's largest musical fountain.[62]

Splash fountains

editA splash fountain or bathing fountain is intended for people to come in and cool off on hot summer days. These fountains are also referred to as interactive fountains. These fountains are designed to allow easy access, and feature nonslip surfaces, and have no standing water, to eliminate possible drowning hazards, so that no lifeguards or supervision is required. These splash pads are often located in public pools, public parks, or public playgrounds (known as "spraygrounds"). In some splash fountains, such as Dundas Square in Toronto, Canada, the water is heated by solar energy captured by the special dark-colored granite slabs. The fountain at Dundas Square features 600 ground nozzles arranged in groups of 30 (3 rows of 10 nozzles). Each group of 30 nozzles is located beneath a stainless steel grille. Twenty such grilles are arranged in two rows of 10, in the middle of the main walkway through Dundas Square.

Drinking fountain

editA water fountain or drinking fountain is designed to provide drinking water and has a basin arrangement with either continuously running water or a tap. The drinker bends down to the stream of water and swallows water directly from the stream. Modern indoor drinking fountains may incorporate filters to remove impurities from the water and chillers to reduce its temperature. In some regional dialects, water fountains are called bubblers. Water fountains are usually found in public places, like schools, rest areas, libraries, and grocery stores. Many jurisdictions require water fountains to be wheelchair accessible (by sticking out horizontally from the wall), and to include an additional unit of a lower height for children and short adults. The design that this replaced often had one spout atop a refrigeration unit.

In 1859, The Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association was established to promote the provision of drinking water for people and animals in the United Kingdom and overseas. More recently, in 2010, the FindaFountain campaign was launched in the UK to encourage people to use drinking fountains instead of environmentally damaging bottled water. A map showing the location of UK drinking water fountains is published on the FindaFountain website.

How fountains work

editFrom Roman times until the end of the 19th century, fountains operated by gravity, requiring a source of water higher than the fountain itself to make the water flow. The greater the difference between the elevation of the source of water and the fountain, the higher the water would go upwards from the fountain.

In Roman cities, water for fountains came from lakes and rivers and springs in the hills, brought into city in aqueducts and then distributed to fountains through a system of lead pipes.

From the Middle Ages onwards, fountains in villages or towns were connected to springs, or to channels which brought water from lakes or rivers. In Provence, a typical village fountain consisted of a pipe or underground duct from a spring at a higher elevation than the fountain. The water from the spring flowed down to the fountain, then up a tube into a bulb-shaped stone vessel, like a large vase with a cover on top. The inside of the vase, called the bassin de répartition, was filled with water up to a level just above the mouths of the canons, or spouts, which slanted downwards. The water poured down through the canons, creating a siphon, so that the fountain ran continually.

In cities and towns, residents filled vessels or jars of water jets from the canons of the fountain or paid a water porter to bring the water to their home. Horses and domestic animals could drink the water in the basin below the fountain. The water not used often flowed into a separate series of basins, a lavoir, used for washing and rinsing clothes. After being used for washing, the same water then ran through a channel to the town's kitchen garden. In Provence, since clothes were washed with ashes, the water that flowed into the garden contained potassium, and was valuable as fertilizer.[5]

The most famous fountains of the Renaissance, at the Villa d'Este in Tivoli, were located on a steep slope near a river; the builders ran a channel from the river to a large fountain at top of the garden, which then fed other fountains and basins on the levels below. The fountains of Rome, built from the Renaissance through the 18th century, took their water from rebuilt Roman aqueducts which brought water from lakes and rivers at a higher elevation than the fountains. Those fountains with a high source of water, such as the Triton Fountain, could shoot water 16 feet (4.9 m) in air. Fountains with a lower source, such as the Trevi Fountain, could only have water pour downwards. The architect of the Trevi Fountain placed it below street level to make the flow of water seem more dramatic.

The fountains of Versailles depended upon water from reservoirs just above the fountains. As King Louis XIV built more fountains, he was forced to construct an enormous complex of pumps, called the Machine de Marly, with fourteen water wheels and 220 pumps, to raise water 162 meters above the Seine River to the reservoirs to keep his fountains flowing. Even with the Machine de Marly, the fountains used so much water that they could not be all turned on at the same time. Fontainiers watched the progress of the King when he toured the gardens and turned on each fountain just before he arrived.[63]

The architects of the fountains at Versailles designed specially-shaped nozzles, or tuyaux, to form the water into different shapes, such as fans, bouquets, and umbrellas.

In Germany, some courts and palace gardens were situated in flat areas, thus fountains depending on pumped pressurized water were developed at a fairly early point in history. The Great Fountain in Herrenhausen Gardens at Hanover was based on ideas of Gottfried Leibniz conceived in 1694 and was inaugurated in 1719 during the visit of George I. After some improvements, it reached a height of some 35 m in 1721 which made it the highest fountain in European courts. The fountains at the Nymphenburg Palace initially were fed by water pumped to water towers, but as from 1803 were operated by the water powered Nymphenburg Pumping Stations which are still working.

Beginning in the 19th century, fountains ceased to be used for drinking water and became purely ornamental. By the beginning of the 20th century, cities began using steam pumps and later electric pumps to send water to the city fountains. Later in the 20th century, urban fountains began to recycle their water through a closed recirculating system. An electric pump, often placed under the water, pushes the water through the pipes. The water must be regularly topped up to offset water lost to evaporation, and allowance must be made to handle overflow after heavy rain.

In modern fountains a water filter, typically a media filter, removes particles from the water—this filter requires its own pump to force water through it and plumbing to remove the water from the pool to the filter and then back to the pool. The water may need chlorination or anti-algal treatment, or may use biological methods to filter and clean water.

The pumps, filter, electrical switch box and plumbing controls are often housed in a "plant room". Low-voltage lighting, typically 12 volt direct current, is used to minimise electrical hazards. Lighting is often submerged and must be suitably designed. High wattage lighting (incandescent and halogen) either as submerged lighting or accent lighting on waterwall fountains have been implicated in every documented Legionnaires' disease outbreak associated with fountains. This is detailed in the "Guidelines for Control of Legionella in Ornamental Features". Floating fountains are also popular for ponds and lakes; they consist of a float pump nozzle and water chamber.

The tallest fountains in the world

edit- King Fahd's Fountain (1985) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The fountain jets water 260 meters (853 feet) above the Red Sea and is currently the tallest fountain in the world.[64]

- The World Cup Fountain in the Han-gang River in Seoul, Korea (2002), advertises a height of 202 meters (663 feet).

- The Gateway Geyser (1995), next to the Mississippi River in St. Louis, Missouri, shoots water 192 meters (630 feet) in the air. It is the tallest fountain in the United States.

- Port Fountain (2006) in Karachi, Pakistan, rises to height of 190 meters (620 feet) making it the fourth tallest fountain.

- Fountain Park, Fountain Hills, Arizona (1970). Can reach 171 meters (561 feet) when all three pumps are operating, but normally runs at 91 meters (300 feet).

- The Dubai Fountain, opened in 2009 next to Burj Khalifa, the world's tallest building. The fountain performs once every half-hour to recorded music, and shoots water to height of 73 meters (240 feet). The fountain also has extreme shooters, not used in every show, which can reach 150 meters (490 feet).

- The Captain James Cook Memorial Jet in Canberra (1970), 147 meters (482 feet)

- The Jet d'eau, in Geneva (1951), 140 meters (460 feet)

- Magic Fountain of Montjuïc (1929), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. 170 Feet, Created by Carles Buïgas. Tallest Fountains in the World

Gallery of notable fountains around the world

edit-

The Fonte Gaia, Piazza del Campo, Siena, Italy by Jacopo della Quercia (1419) (replaced by a copy in 1868)

-

The Schöner Brunnen (Beautiful Fountain) in Nuremberg, Germany. (1385–96)

-

Samson and the Lion Fountain (1800–02), Peterhof, Russia

-

Buckingham Fountain (1927) in Chicago

-

Dubai Fountain (2008), a computer-programmed musical fountain, is 250 m (820 ft) long and can jet water 150 m (490 ft) into the air

-

The El Alamein Fountain (1959–61) in Sydney, designed by Robert Woodward, was the first "dandelion" fountain

-

The Emil Aaltonen Memorial (1969), a 4.5 metres (15 ft) tall fountain at the Tammela Square in Tampere, designed by Raimo Utriainen

-

Fountains in the Park of the Reserve, Lima, Peru

See also

edit- Wishing well, for the practice of dropping coins into fountains

Bibliography

edit- Helen Attlee, Italian Gardens – A Cultural History. Frances Lincoln Limited, London, 2006.

- Paris et ses Fontaines, del la Renaissance a nos jours, edited by Béatrice de Andia, Dominique Massounie, Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy and Daniel Rabreau, from the Collection Paris et son Patrimoine, Paris, 1995.

- Les Aqueducs de la ville de Rome, translation and commentary by Pierre Grimal, Société d'édition Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1944.

- Louis Plantier, Fontaines de Provence et de la Côte d'Azur, Édisud, Aix-en-Provence, 2007

- Frédérick Cope and Tazartes Maurizia, Les Fontaines de Rome, Éditions Citadelles et Mazenod, 2004

- André Jean Tardy, Fontaines toulonnaises, Les Éditions de la Nerthe, 2001. ISBN 2-913483-24-0

- Hortense Lyon, La Fontaine Stravinsky, Collection Baccalauréat arts plastiques 2004, Centre national de documentation pédagogique

- Marilyn Symmes (editor), Fountains-Splash and Spectacle- Water and Design from the Renaissance to the Present. Thames and Hudson, in cooperation with the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. (1998).

- Yves Porter et Arthur Thévenart, Palais et Jardins de Perse, Flammarion, Paris (2002). (ISBN 978-2-08-010838-8).

- Raimund O.A. Becker-Ritterspach, Water Conduits in the Kathmandu Valley, Munshriram Manoharlal Publishers, Pvt.Ltd, New Delhi 1995, ISBN 81-215-0690-5

References

edit- ^ Philippe Prévot, Histoire des jardins, Editions Sud Ouest, Bordeaux, 2006.

- ^ SAMIRAD (Saudi Arabia Market Information Resource Directory)

- ^ "fountain". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, 1.59

- ^ a b Louis Plantier, Fontaines de Provence et de la Côte d'Azur, Édisud, Aix-en-Provence, 2007

- ^ Frontin, Les Aqueducs de la ville de Rome, translation and commentary by Pierre Grimal, Société d'édition Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1944.

- ^ Philippe Prevot, pg. 20

- ^ Philippe Prevot, pg. 21

- ^ Water Conduits in the Kathmandu Valley (2 vols.) by Raimund O.A. Becker-Ritterspach, ISBN 9788121506908, Published by Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India, 1995

- ^ Psalms 36:9; Proverbs 13:14; Revelation 22:1; Dante's Paradisio XXV 1–9.

- ^ Molina, Nathalie, 1999: Le Thoronet Abbey, Monum – Éditions du patrimoine.

- ^ Marilyn Simmes, Fountains, Splash and Spectacle. pg.63

- ^ Allain and Christiany, L'Art des jardins en Europe This type of "water joke" later became popular in Renaissance and baroque gardens.

- ^ Yves-Marie Allain and Janine Christiany, L'Art des jardins en Europe, Citadelles & Mazenod, Paris, 2006

- ^ According to the Qur'an, the dead going to paradise would be given water from the spring Salsabil: "And there they will be given a cup whose mixture is of Zanjabil (ginger). A fountain there, called Salsabil." (76:17–18)

- ^ Bent Sorensen (November 1995), "History of, and Recent Progress in, Wind-Energy Utilization", Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 20: 387–424, doi:10.1146/annurev.eg.20.110195.002131

- ^ Banu Musa (1979), The book of ingenious devices (Kitāb al-ḥiyal), translated by Donald Routledge Hill, Springer, p. 44, ISBN 90-277-0833-9

- ^ Yves Porter and Arthur Thevenart, Palais et Jardins de Perse, pg. 40.

- ^ Azraqi, H. Massé, Anthologie persane, pg. 44. English translation of excerpt by D.R. Siefkin.

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan. The Crank-Connecting Rod System in a Continuously Rotating Machine Archived 12 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ See the official site of the Alhambra complex for the history of the fountains

- ^ Allain and Christiany, L'art des jardins en Europe . See also See the official site of the Alhambra complex for the history of the fountains

- ^ Naomi Miller, Fountains as Metaphor, in Fountains- Splash and Spectacle -Water and Design from the Renaissance to the Present, edited by Marilyn Symmes, London, 1998.

- ^ Helena Attlee, Italian Gardens, A Cultural History, pp. 11–12

- ^ Pinto, John A. The Trevi Fountain. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1986.

- ^ The fountain in Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere originally had two upper basins, but the water pressure in the early Renaissance was so low that the water was unable to reach the upper basin, so the top basin was removed.

- ^ cited in Helena Attlee, Italian Gardens, a Cultural History, p. 21

- ^ Symmes, Fountains – Splash and Spectacle, pg. 126

- ^ Marilyn Symmes, Fountains- Splash and Spectacle- Water and Design from the Renaissance to the Present. pg. 78

- ^ Helena Attlee, Italian Gardens – A Cultural History, p. 30

- ^ a b Helena Attlee, Italian Gardens – A Cultural History

- ^ Marion Boudon, "La Fontaine des Innocents", in Paris et ses fontaines, de la Renaissance à nos jours, 1995.

- ^ Le Guide du Patrimoine en France, Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux, 2009

- ^ A. Muesset, Les Francinis, Paris, 1930, cited in Luigi Gallo, La Présence italienne au 17e siècle, in Paris et ses fontaines de la Renaissance à nos jours, Collection Paris et son patrimoine, (1995).

- ^ Luigi Gallo, La Présence italienne au 17e siècle, in Paris et ses fontaines de la Renaissance à nos jours, Collection Paris et son patrimoine,

- ^ Katherine Wentworth Rinne, The Fall and Rise of the Waters of Rome, collected in Marilyn Symmes, Fountains- Splash and Spectacle. (pg. 54).

- ^ Wentworth Rinne, The Fall and Rise of the Waters of Rome, collected in Marilyn Symmes, Fountains- Splash and Spectacle. (pg. 54).

- ^ a b c Maria Ann Conneli and Marilyn Symmes, Fountains as propaganda, in Fountains, Splash and Spectacle – Water and Design from the Renaissance to the Present. Edited by Marilyn Symmes. Thames and Hudson, London

- ^ Conelli and Symmes, p. 90

- ^ Allain and Christiany, L'art des jardins en Europe

- ^ Robert W. Berger, The Chateau of Louis XIV, University Park, PA. 1985, and Gerald van der Kemp, Versailles, New York, 1978.

- ^ Alexandre Orloff and Dimitri Chvidkovski, Saint-Petersbourg, l'architecture des tsars Editions Place des Victoires, Paris, 2000.

- ^ Katia Frey, L'enterprise napoléonienne, in Paris et ses fontaines, p. 104.

- ^ Beatrice Lamoitier, L'Essor des fontaines monumentales, in Paris et ses fontaines. pg. 171.

- ^ Beatrice LaMoitier, "Le Règne de Davioud", in Paris et ses fontaines, pg. 180

- ^ Ric Burns and James Sanders, New York, an Illustrated History, Alfred Knopf, New Yorkm, 1999, pg. 78–79.

- ^ a b Stephen Astley, The Fountains in Trafalagar Square, in Fountains- Splash and Spectacle – Water and Design from the Renaissance to the Present, edited by Marilyn Symmes, 1998.

- ^ Virginie Grandval, Fontaines éphéméres, in Paris et ses fontaines, pg. 209–247

- ^ Figures cited by Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy, Doctor of the History of Art at the University of Paris IV - Sorbonne, in her essay on fountains, 1900-1940- Entre tradition et modernité, in Paris et ses fontaines, pg. 257.

- ^ Pollak, Ellen (16 February 2016). "'Fountain Lady': Ruth Asawa in San Francisco". Broad Strokes Blog. National Museum of Women in the Arts. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Halprin, Lawrence, Notebooks 1959–1971, Cambridge Massachusetts (1972)

- ^ From the label on the fountain displayed at the Moscow bienalle of contemporary art, October 2009. To see a short documentary about Bit.Fall, BitFall project

- ^ a b "Artropolis". Merchandise Mart Properties, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 November 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- ^ "Crown Fountain". Archi•Tech. Stamats Business Media. July–August 2005. Archived from the original on 2 December 2006. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- ^ "Chicago's stunning Crown Fountain uses LED lights and displays". LEDs Magazine. PennWell Corporation. May 2005. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- ^ "The Pneumatics of Hero of Alexandria". Archived from [v the original] on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Montaigne, M. E.. de, Journal de voyage en Italie, Le Livre de poche, 1974.

- ^ Fontaines éphéméres, in Paris et ses fontaines, pg. 209–247

- ^ Virginie Grandval, pg. 229

- ^ "About fountain :: Europe's largest floating fountain". www.fountainroshen.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "High One Resort South Korea - Gangwon-do - Attraction Review". Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Marilyn Symmes, "Fountains as Propaganda", in "Fountains, Splash and Spectacle", pp. 82–83

- ^ Steve (27 June 2015). "Top 6 Tallest Fountains in the World". Life in Saudi Arabia. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

External links

editKing Fahd Fountain tops in the World as Tallest fountain