In particle physics, a gauge boson is a bosonic elementary particle that acts as the force carrier for elementary fermions.[1][2] Elementary particles whose interactions are described by a gauge theory interact with each other by the exchange of gauge bosons, usually as virtual particles.

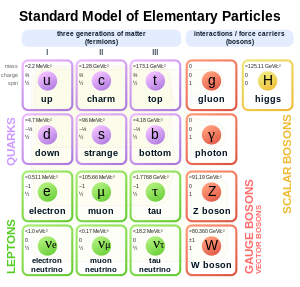

Photons, W and Z bosons, and gluons are gauge bosons. All known gauge bosons have a spin of 1; for comparison, the Higgs boson has spin zero and the hypothetical graviton has a spin of 2. Therefore, all known gauge bosons are vector bosons.

Gauge bosons are different from the other kinds of bosons: first, fundamental scalar bosons (the Higgs boson); second, mesons, which are composite bosons, made of quarks; third, larger composite, non-force-carrying bosons, such as certain atoms.

Gauge bosons in the Standard Model

editThe Standard Model of particle physics recognizes four kinds of gauge bosons: photons, which carry the electromagnetic interaction; W and Z bosons, which carry the weak interaction; and gluons, which carry the strong interaction.[3]

Isolated gluons do not occur because they are colour-charged and subject to colour confinement.

Multiplicity of gauge bosons

editIn a quantized gauge theory, gauge bosons are quanta of the gauge fields. Consequently, there are as many gauge bosons as there are generators of the gauge field. In quantum electrodynamics, the gauge group is U(1); in this simple case, there is only one gauge boson, the photon. In quantum chromodynamics, the more complicated group SU(3) has eight generators, corresponding to the eight gluons. The three W and Z bosons correspond (roughly) to the three generators of SU(2) in electroweak theory.

Massive gauge bosons

editGauge invariance requires that gauge bosons are described mathematically by field equations for massless particles. Otherwise, the mass terms add non-zero additional terms to the Lagrangian under gauge transformations, violating gauge symmetry. Therefore, at a naïve theoretical level, all gauge bosons are required to be massless, and the forces that they describe are required to be long-ranged. The conflict between this idea and experimental evidence that the weak and strong interactions have a very short range requires further theoretical insight.

According to the Standard Model, the W and Z bosons gain mass via the Higgs mechanism. In the Higgs mechanism, the four gauge bosons (of SU(2)×U(1) symmetry) of the unified electroweak interaction couple to a Higgs field. This field undergoes spontaneous symmetry breaking due to the shape of its interaction potential. As a result, the universe is permeated by a non-zero Higgs vacuum expectation value (VEV). This VEV couples to three of the electroweak gauge bosons (W+, W− and Z), giving them mass; the remaining gauge boson remains massless (the photon). This theory also predicts the existence of a scalar Higgs boson, which has been observed in experiments at the LHC.[4]

Beyond the Standard Model

editGrand unification theories

editThe Georgi–Glashow model predicts additional gauge bosons named X and Y bosons. The hypothetical X and Y bosons mediate interactions between quarks and leptons, hence violating conservation of baryon number and causing proton decay. Such bosons would be even more massive than W and Z bosons due to symmetry breaking. Analysis of data collected from such sources as the Super-Kamiokande neutrino detector has yielded no evidence of X and Y bosons.[citation needed]

Gravitons

editThe fourth fundamental interaction, gravity, may also be carried by a boson, called the graviton. In the absence of experimental evidence and a mathematically coherent theory of quantum gravity, it is unknown whether this would be a gauge boson or not. The role of gauge invariance in general relativity is played by a similar[clarification needed] symmetry: diffeomorphism invariance.

W′ and Z′ bosons

editW′ and Z′ bosons refer to hypothetical new gauge bosons (named in analogy with the Standard Model W and Z bosons).

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Gribbin, John; Gribbin, Mary; Gribbin, Jonathan (2000). Q is for quantum: an encyclopedia of particle physics. New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-85578-3.

- ^ Clark, John Owen Edward, ed. (2004). The essential dictionary of science. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-0-7607-4616-5.

- ^ Veltman, Martinus (2003). Facts and mysteries in elementary particle physics. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-238-148-4.

- ^ "CERN and the Higgs boson". CERN. October 2013. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.