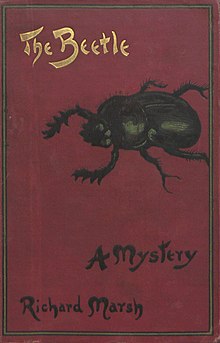

The Beetle (or The Beetle: A Mystery) is an 1897 fin de siècle horror novel by British writer Richard Marsh, in which a shape-shifting ancient Egyptian entity seeks revenge on a British member of Parliament. The novel initially sold more copies than Bram Stoker's Dracula, a similar horror story published in the same year.

| |

| Author | Richard Marsh |

|---|---|

| Genre | Horror fiction |

| Publisher | Skeffington & Son |

Publication date | September 1897 (1st collected edition) |

| Publication place | London, United Kingdom |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 351 |

| OCLC | 267113228 |

Plot summary

editThe Beetle is told from the point of view of four narrators: Robert Holt, Sydney Atherton, Marjorie Lindon, and Augustus Champnell.

The novel begins by retelling an account of Robert Holt, a clerk who has been searching for a job all day. Denied food and water at a workhouse, he continues to walk in the dark through the rain until he comes upon an abandoned, dilapidated house with an open window. There he finds shelter and meets a monstrous figure, the mysterious Beetle.

The Beetle takes control of Holt's mind through mesmerism, allowing him to take human form, and then accuses Holt of being a thief and promises to treat him like one. Then the Beetle forces Holt to take off his clothes and put on new ones in exchange for food and shelter. After that, the Beetle forces a kiss on Holt, which weakens him.

The Beetle plans to send Holt to the home of Paul Lessingham, a member of the House of Commons, to steal the letters from the drawer in his desk. When Holt encounters Lessingham, he is to say "the Beetle," which would hinder him. Holt succeeds because the Beetle can control him, but Lessingham captures Holt before he can leave with the letters. Holt shouts "the Beetle" twice, in a voice that is not his own, causing Lessingham to shiver in a corner. Holt jumps through a window and escapes. On the street, he is approached by another man, Sydney Atherton, who asks him if he committed a crime against Lessingham. When Holt answers truthfully, Atherton is pleased and lets him go. Holt delivers the letters to the Beetle, who realizes that they are love letters from a certain Marjorie Lindon. The Beetle plans to use her to harm Lessingham.

The narrative perspective switches to Sydney Atherton, who turns out to be Paul Lessingham's romantic rival for the affection of Marjorie Lindon. On the night of Holt's robbery, Atherton proposes to Lindon at a ball. She tells him that she is already engaged to Lessingham but that the engagement has been kept secret because her father is Lessingham's political opponent. Lindon asks Atherton to intercede with her father on Lessingham's behalf, knowing that her father considers Atherton like a son. Consumed by self-pity and anger, Atherton leaves the ball.

After meeting Holt, Atherton visits Lessingham, who insists that he and Lindon are not engaged before sending him away. In his anger, Atherton plans to spend the next day working on his chemical warfare inventions in his laboratory. The Beetle approaches Atherton in his laboratory and tries to mesmerise him like Holt, but Atherton is able to resist. The Beetle then introduces himself as a child of Isis and promises him Lindon's love if he agrees to help him. Atherton notices that the Beetle has the eyes of a skilled hypnotist and does not decline.

The Beetle leaves, and, shortly after that, Lessingham arrives at Atherton's laboratory. Lessingham apologizes for his rudeness the previous night and asks Atherton not to speak to anyone about it, as he does not want to be bothered by rumours. Atherton agrees, which prompts Lessingham to ask some questions about ancient superstitions and religions, which Atherton has some knowledge of. As Lessingham is about to leave, he sees a picture of a scarab on a shelf and enters a catatonic state, similar to what happened to him when Holt uttered "the Beetle." Atherton brings him out of it and promises him not to tell anyone what he just witnessed.

That night, Atherton goes to a ball and manages to secure financing for his experiments from a woman named Dora Grayling. They arrange to meet the next day. Atherton is then approached by his friend, Percy Woodville, whom he takes to the House of Commons to hear Lessingham speak. Lindon is there too, and an altercation between Lindon and Atherton is avoided when Marjorie's father finds out about her and Lessingham, and Lindon runs off with her fiancé. Enraged, Atherton takes Woodville to his laboratory for a demonstration, picking up a stray cat on the way. He uses a concoction of his to kill the cat, fatally wounding Woodville in the process. Atherton brings Woodville to the Beetle and agrees to help him in exchange for his friend's survival. Atherton escapes hypnosis and convinces the Beetle that he too has magic that can make anyone talk. The Beetle tells him that Lessingham killed a woman he was close to in Egypt. When Atherton asks the Beetle why the picture of a scarab frightened Lessingham, the Beetle denies any knowledge. Atherton threatens him, and the Beetle transforms into a scarab. When Atherton tries to capture it, the Beetle changes shape again and flees.

Atherton has forgotten about the appointment and is surprised by Grayling's visit the next day. He does not know that Grayling has feelings for him, and makes several insensitive remarks that cause her to leave in anger. Later, Marjorie Lindon's father visits to talk about how Lessingham is not an appropriate match for his daughter. When Atherton receives a third surprise visit, from Marjorie, her father hides and eavesdrops on their conversation. Marjorie tells him about a half-naked and starving man (Holt) she brought to her house yesterday without her father's knowledge after finding him lying in the street. The man had mentioned that Lessingham was in danger, and she wanted to know more about it. Atherton suspects it is the same man he saw leaving Lessingham's house two nights ago but does not mention it. Marjorie tells him that she, too, had been attacked by an unseen force that sounded like a beetle. Her father then emerges from his hiding place and accuses her of insanity. Both Lindons leave the house in an agitated state. The fourth coincidental visitor is Lessingham, who wants to know what Atherton has to do with the picture of the scarab and everything else that happened. Although neither speaks openly about it, they agree that Lessingham is haunted, and that if he ensures Lindon won't be dragged into it, Atherton will give him the benefit of the doubt regarding his innocence. Finally, Grayling returns, still wishing to lunch, and Atherton accepts.

The narrative perspective switches again, this time to Marjorie Lindon. Arriving home, Lindon finds that her guest, Holt, is awake, and he tells her his story. Astonished, Lindon sends her servants to fetch Atherton, because she has no one else to turn to. When Atherton arrives, he interrogates Holt enough to confirm his suspicions, but he hopes to keep Lindon out of the matter. He fails, however, and Lindon insists that she go along in search of the Beetle. The three manage to find the house, but it is deserted. Suddenly, Holt is hypnotised again and runs out. Atherton and Lindon agree that he should follow Holt and that she will stay in the house in case the Beetle returns, and that he will send anyone he finds to the house to help her. Only minutes later, Lindon finds that the Beetle is hiding in the house, and her account ends abruptly as she is captured by the Beetle.

The final narrative is given from the perspective of Detective Augustus Champnell. Champnell is finishing up the paperwork on a case when Lessingham enters his office. Lessingham tells him about his connection to the Beetle. Twenty years ago, Lessingham decided to go to Cairo. Out on his own one night, he was lured by a young woman and was captured by the cult of Isis. In her temple, Lessingham was put into a hypnotic state and forced to obey the orders of the high priestess, called the Woman of the Songs. There he witnessed many human sacrifices, all of them women. After one such sacrifice, the Woman of the Songs' control over him weakened, and he took the opportunity to attack and strangle her until she turned into a scarab. He managed to escape the temple and was found by missionaries and nursed back to health, after which he returned to England. As Lessingham explains his current situation to Champnell, Atherton, a friend of Champnell's, bursts in. Having returned to the house after losing sight of the hypnotized Holt, he discovered that Lindon was missing; he asks Champnell for help in finding her.

The three men quickly make their way to the Beetle's house, but all they find are Lindon's clothes and hair. They inquire at the only other house on the street, which belongs to a Louisa Coleman. She also owns the Beetle's house. She explains that she rented the house to the Beetle, but because she was suspicious, she spied on him. She never saw Lindon leave, but she did see a man leave the house, and shortly after that, she also saw the Beetle leave, carrying a human-sized package. Champnell theorises that the Beetle intends to return to Egypt and that the man was Lindon, dressed in Holt's old clothes. After acquiring information from an officer, the three men follow the Beetle to London Waterloo, where they learn that the Beetle boarded a train with two peculiar Englishmen. At the local police station, the men learn that a man who was previously in the company of an "Arab" has been found murdered. It turns out to be Holt, but he is in fact still barely alive. Before he collapses, he asks Atherton to save Lindon and confirms that she is the other man. With the help of the police, they find out that the Beetle and Lindon took a train from London St Pancras to Hull. They are provided with a special train to catch up with the kidnapper, but their journey ends in Luton, where the train they had been pursuing has derailed. In the chaos, they find Lindon unconscious in one of the front coaches. All that is left of the Beetle are burnt and bloodied rags.

Champnell concludes his narrative by saying the events took place several years ago. Lindon has since married Lessingham, who has become a great politician. Atherton and Grayling married after Atherton came to understand the feelings between them. Holt lies buried in Kensal Green Cemetery under an expensive tombstone. As for the children of Isis, Champnell has learned from good sources that, during an expeditionary advance to Dongola, a temple and its occupants - victims of an explosion - were discovered. The corpses were neither men nor women but monstrous creatures, and the remnants of scarab artifacts lay scattered about. Champnell declines to investigate further but hopes that the temple was the one Lessingham spoke of.

Characters

editSydney Atherton: An inventor whose expertise is chemical warfare. He is a childhood friend of Marjorie Lindon and is romantically interested in her.

The Beetle/The Arab: The supernatural antagonist of the novel, he is a member of an Egyptian cult that worships Isis. He uses the name Mohamed el Kheir for business, but it is unlikely that this is his real name.

Augustus Champnell: A detective with knowledge of the supernatural. Also appeared in The House of Mystery (1898) and four short stories later collected in The Aristocratic Detective (1900).

Louisa Coleman: The owner of the house that the Beetle lives in during his stay in England.

Dora Grayling: A wealthy woman who is in love with Sydney Atherton.

Robert Holt: An unemployed clerk who unknowingly enters the house of the Beetle and is forced into his service through hypnosis.

Paul Lessingham: A member of the House of Commons and a rising star within the British political establishment. He is Marjorie Lindon's secret fiancé, and the Beetle's main target.

Marjorie Lindon: The daughter of a politician and the fiancée of Paul Lessingham. The engagement is kept secret because Lessingham and her father have opposing political views.

Mr. Lindon: Marjorie's father, a widower and politician.

The Woman of Songs: A member of an Egyptian cult that worships Isis. It is implied, but not confirmed, that she and the Beetle are one and the same.

Percy Woodville: A friend of Atherton and another one of Lindon's suitors.

Publication

editThe Beetle sold out after its first printing and continued to be published into the 20th century. It initially sold more copies than Bram Stoker's Dracula, which was published in the same year.[1][2][3] Minna Vuohelainen has suggested that the novel's serialisation in Answers, where it was first published on 13 March 1897, indicates a larger audience. The entire story was made available over a fifteen-week period ending 19 June. The novel was also published in one volume by a religious publishing house. The title was changed from The Peril of Paul Lessingham: The Story of a Haunted Man to The Beetle: A Mystery.[4]

Vuohelainen provides context for the reappearance of The Beetle by tracing its appearance in Hugh and Graham Greene's collection Victorian Villainies, which includes a note from the editors that they had "long felt that The Beetle [was] a book which should not be out of print." The note was also included in the first annotated scholarly edition of The Beetle, published by Broadview Press in 2004.

Scholarly criticism

editRecently, scholars have taken a renewed interest in Marsh's work. Critics have found The Beetle to be a rich source for analysis for areas such as postcolonial studies, women's studies, post-structuralism and psychoanalytic studies, narrative studies, and new materialism studies. Research on this text is both abundant and diverse, focusing on narrative and genre, imperialism, alterity, gender performativity, and identity. Scholars such as Minna Vuohelainen, Jack Halberstam,[5] and Roger Luckhurst[citation needed] have discussed The Beetle as an example of the gothic genre. At the same time, scholars like Rhys Garnett[6] and Victoria Margree began to develop critical arguments that balanced a discussion of imperialism with Victorian anxieties about gender and sexuality.

The Beetle as gothic fiction

editMany scholars touch on at least the genre, narrative, or form of The Beetle in their studies because it differs in all three categories. Minna Vuohelainen's research focuses on the reception and form of the novel.[4] The illustrations included in the first edition help to define arguments about publication and audience, and the change in narrative perspective in The Beetle helps make the arguments about serialisation and reception. Themes, motifs, and plot elements such as found-documents, crime, police work, engagement with ancient cultures, complicated love triangles, the uncanny, and monstrosity also point to a strong connection with the gothic mystery genre.[citation needed]

Postcolonial criticism

editSome scholars, such as Victoria Margree, place The Beetle in the context of imperialism, colonisation, or sovereignty.[7] The Beetle locates itself in the context of non-Christian spaces outside of a European context, and the novel's title character, the Beetle, is constantly referred to by other characters in the story only as an "Arab." This has led critics to call The Beetle an imperial gothic novel.[citation needed] The Beetle returns to haunt British MP Paul Lessingham, who killed a priestess from the cult of Isis in Egypt twenty years before. Scholars have used Said's theory of orientalism to provide productive arguments for engaging this text with a non-European context. Modern scholars such as Ailise Bulfin have attempted to separate appropriated cultural tradition from ambiguity of the text in order to make productive historical arguments about British Imperialism reflected in the novel's genre. For example, Bulfin points to the creation of the Suez Canal and the specifically Egyptian context the novel provides to understand imperial anxieties in Victorian England.[8]

Women and Gender studies criticism

editLeslie Allin,[9] Kristen Davis,[10] Dawn Vernooy and W.C. Harris,[11] and Victoria Margree[7] have contributed to a critical understanding of how gender and sexuality interact with interpretive statements about genre, narrative, and realm. The Beetle character presents gender and sexuality in ways that the text makes ambiguous. This has helped queer theorists like Thomas Stuart to destabilize assumptions about the social construction of gender in Victorian England.[12] In particular, the Beetle demands that Holt undresses before taking the form of an ailing male figure with a complicated female presence and then kissing him. Sydney Atherton is another complicated character, obsessed with his own masculinity in comparison to his romantic rival Lessingham. In addition, Marjorie Lindon defies the expectations of the female gender by refusing to be controlled by the male characters in the novel, whether they are members of her family or seeking her affection.[citation needed]

Contemporary criticism

editThomas Stuart,[12] Anna Maria Jones,[13] and Graeme Pedlingham[14] have made connections between the indeterminacy they perceived in The Beetle and new materialisms. They have attempted to explain the mutability of objects and the object relations that inform the novel's characters and motifs. For example, Jones makes connections to thermodynamics and the law of conservation of energy to make arguments for the scientific and social anxieties addressed in The Beetle. Although the novel has only attracted scholarly interest since its republication in the 1980s, it has been discussed in various interpretive approaches.[13]

Film, stage and radio adaptations

editIn November 1919, the British silent film, The Beetle, directed by Alexander Butler and starring Maudie Dunham and Hebden Foster, was released.[15] The silent version is considered lost. Nine years later, in October 1928, a stage adaptation by producer and playwright J. B. Fagan, starring Catherine Lacey, was performed at the Strand Theatre.[16] Another adaptation, written by Roger Danes, was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 in 1997; it was repeated in 2014[17] and 2021.

References

edit- ^ Davies, David Stuart (2007). Introduction to Wordsworth Editions reprint.

- ^ Jenkins, J. D. (ed.) (n.d.). "The Beetle (1897)". Retrieved 3 November 2018, from http://www.valancourtbooks.com/the-beetle-1897.html

- ^ "The Beetle". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b Vuohelainen, Minna (2006). "Richard Marsh's The Beetle (1897): late-Victorian Popular Novel". Working With English: Medieval and Modern Language, Literature and Drama. 2 (1): 89-100

- ^ Halberstam, Judith (2002). "Gothic Nation: The Beetle by Richard Marsh". In Smith, Andrew; Mason, Diane; Hughes, William (eds.). Fictions of Unease: The Gothic from Otranto to The X-Files. Bath: Sulis Press.

- ^ Garnett, Rhys (1990), Garnett, Rhys; Ellis, R. J. (eds.), "Dracula and the Beetle: Imperial and Sexual Guilt and Fear in Late Victorian Fantasy", Science Fiction Roots and Branches, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 30–54, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-20815-9_4, ISBN 978-0-333-46909-5, retrieved 14 December 2021

- ^ a b Margree, Victoria (2007). "'Both in Men's Clothing': Gender, Sovereignty and Insecurity in Richard Marsh's The Beetle". Critical Survey. 19 (2): 63–81. doi:10.3167/cs.2007.190205. ISSN 0011-1570.

- ^ Bulfin, Ailise (2018). "‘In that Egyptian den’: situating The Beetle within the fin-de-siècle fiction of Gothic Egypt". In V. Margree, D. Orrells, & M. Vuohelainen (Eds.), Richard Marsh, popular fiction and literary culture, 1890–1915: Rereading the fin de siècle (pp. 127–147). Manchester University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv18b5f6c.12

- ^ Allin, Leslie (2015). "Leaky Bodies: Masculinity, Narrative and Imperial Decay in Richard Marsh's The Beetle". Victorian Network. 6 (1): 113–135. doi:10.5283/vn.58. ISSN 2042-616X.

- ^ Davis, Kristen J. (2018). "Colonial Syphiliphobia: Sexual Deviance and Disease in Richard Marsh's The Beetle". Gothic Studies. 20 (1–2): 140–154. doi:10.7227/GS.0040. S2CID 165842346.

- ^ Harris, W. C., and Dawn Vernooy (2012). "'Orgies of Nameless Horrors': Gender, Orientalism, and the Queering of Violence in Richard Marsh's The Beetle". Paperson Language and Literature: A Journal for Scholars and Critics of Language and Literature. 48 (4): 338–381.

- ^ a b Stuart, Thomas M. (2018). "Out of Time: Queer Temporality and Eugenic Monstrosity". Victorian Studies. 60 (2): 218–227. doi:10.2979/victorianstudies.60.2.07. ISSN 0042-5222. JSTOR 10.2979/victorianstudies.60.2.07. S2CID 149707352.

- ^ a b Jones, Anna Maria (2011). "Conservation of Energy, Individual Agency, and Gothic Terror in Richard Marsh's The Beetle, or, What's Scarier than an Ancient, Evil, Shape-shifting Bug?". Victorian Literature and Culture. 39 (1): 65–85. doi:10.1017/S1060150310000276. ISSN 1060-1503. JSTOR 41307851. S2CID 159772512.

- ^ Pedlingham, Graeme (2018). "‘Something was going from me – the capacity, as it were, to be myself’: ‘transformational objects’ and the Gothic fiction of Richard Marsh". In V. Margree, D. Orrells, & M. Vuohelainen (eds.), Richard Marsh, popular fiction and literary culture, 1890–1915: Rereading the fin de siècle (pp. 171–189). Manchester University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv18b5f6c.14

- ^ Rigby, Jonathan (2004). English gothic : a century of horror cinema (3rd ed.). London: Reynolds & Hearn. p. 16. ISBN 1-903111-79-X. OCLC 56448498.

- ^ Rigby, Jonathan (April, 1999). "Nothing Like a Grande Dame", Shivers 64.

- ^ "BBC - The Beetle - Media Centre". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

External links

edit- The Beetle at Standard Ebooks

- The Beetle: A Mystery at Project Gutenberg

- The Beetle public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Rutigliano, Olivia (16 April 2020). "This Is the Book That Outsold Dracula in 1897". CrimeReads. Retrieved 23 March 2024.