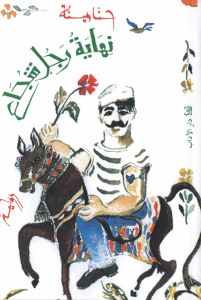

The End of a Brave Man (Arabic: نهاية رجل شجاع, romanized: Nihayat Rajul Shujaa) is a 1989 novel by Syrian author Hanna Mina. Set in coastal Syria during the French Mandate, the coming-of-age story concerns the life of Mufid, a strong, working-class man who struggles with authority and his own sense of virtue. The novel's themes of masculinity and humanity play out during Mufid's two stints in prison, his marriage, the amputation of his leg, and his death.

| |

| Author | Hanna Mina |

|---|---|

| Original title | نهاية رجل شجاع |

| Language | Arabic |

| Genre | Historical fiction, Bildungsroman |

| Set in | Syria |

| Published | 1989 |

| Publisher | Dar al-Adab (Beirut) |

| Publication place | Syria |

| Media type | Print (paperback) |

| ISBN | 9789953890463 |

| OCLC | 4770223127 |

The novel was adapted into a 1994 television miniseries starring Ayman Zeidan as Mufid and directed by Najdat Anzour.

Plot summary

editMufid is a young man from a rural village near the coastal town of Baniyas in Syria. He lives there during the French occupation in the first half of the 20th century with his father, a farmer who is overbearing and violent with him. At the age of 12, Mufid cuts off the tail of a donkey, angering the people from the village and earning him the nickname "Mufid al-Wahsh" ("Mufid the Beast"). His father punishes him by tying him to the trunk of a tree and beating him in view of the villagers. Like his father, Mufid is physically strong, courageous, and has a tendency towards violence.[1]

Mufid drops out of school and runs away from the village, making his way to Baniyas. Following an altercation with a French colonial officer, he is imprisoned for two years. He is held in Latakia at first and then later transferred to a prison in Aleppo. In prison he receives advice on how to live from fellow prisoner Abd al-Jalil, a friend of one of his relatives.

After Mufid leaves prison, he moves to Latakia. He marries a woman named Labiba and struggles to find consistent employment, working as a porter, a sailor and as an assistant to a baker. He tries to remain a virtuous person, but succumbs to economic pressures and is drawn into the criminal underworld of the port city. He learns about city life and maturity from Abdush, a gang leader who is from the same village as him. Mufid finds self-worth in standing up to rival gangs and fighting against the French occupation.

Mufid finds himself caught in a war between rival gangs and the dock workers' demands for unionisation, putting them at odds with both the French Mandate authorities and local employers.[1] He fights with rival gang leader Mu'allim Yusuf al-Bathish in the port but is stopped by authorities. Following a brawl, Mufid is arrested and again sent to prison in Latakia.

Mufid returns to prison for five years. During his incarceration the prison physician diagnoses him with diabetes, but he receives no treatment. Upon his release, A physician amputates his leg above the knee. After the amputation he is depressed and dreams of having a prosthetic leg. His trajectory veers towards self-annihilation and he ignores the advice of his physician, smoking and drinking. Mufid then kills a man before he takes his own life.

Themes and analysis

editAs a coming-of-age story, The End of a Brave Man can be considered a Bildungsroman, with the events of Mufid's life continually returning to themes of humanity and masculinity.[1] His humanity is contrasted with his animal-like nature. While Mufid himself has the physical attributes of an animal, he fears that his animalistic side could undermine his masculinity.[1] Through Mufid, Mina questions the nature of manhood, invoking a binary distinction of animal and man by using the nickname "the Beast" and employing metaphors such as "stallion-hood" to describe his virility.[1]

The End of a Brave Man presents themes of masculinity and cyclical violence as experienced through the life of the protagonist. Mufid is confronted with contradictory masculinities during his life—while he was brutalised by both his father and teacher as a boy, he later finds a positive and nurturing male role model in one of his fellow prisoners.[2] Max Weiss, in Revolutions Aesthetic: A Cultural History of Ba'thist Syria writes that the traditional conception of manhood and masculinity portrayed in the novel "falls in line with the discourse of Asadist-Ba'thist cultural revolution on heroism".[1]

As a novelist, Mina was known for using the period of French colonialism in Syria to offer critiques of contemporary politics.[3] Literary historians argue that Mina's use of the French occupation served as a literary device enabling him to avoid problematic associations with the contemporary Syrian regime.[1]

The story's depiction of Mufid as an amputee was credited with presenting "a positive image of person with physical disabilities who is exposed to chronic diseases that did not prevent them from continuing their normal lives".[4][5]

Television adaptation

editThe End of a Brave Man was adapted into a 1994 Syrian television miniseries of the same name (Nihayat Rajul Shujaa). The series was directed by Najdat Anzour and starred Ayman Zeidan as Mufid.[6] The series had minor differences with the novel and was produced by Sharikat al-Sham al-Duwaliyya (Damascus International), a private company owned by the son of Syrian vice president Abdul Halim Khaddam.[7]

Nihayat Rajul Shujaa was broadcast on Syrian television during Ramadan in 1994, continuing the tradition of airing stories promoting national identity during the holy month.[8] It was broadcast in the second Ramadan time slot in the evening.[7]

The series was well-received, earning praise for its tight plot as well as its portrayal of a noble and valiant Syrian resistance to French colonialism.[3][7] Due to its high production values, particularly its cinematography and musical score, it was considered a breakthrough in the quality of Syrian dramas.[7] The series has been reaired on Arab satellite television.[6]

References

edit- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Weiss, Max (2022). Revolutions Aesthetic: A Cultural History of Ba'thist Syria. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-3196-0.

- ^ El-Helou, Rouba (2019). "Down and Out in Syria and Lebanon: Media Portrayals of Men and Masculinities. Towards a Research Agenda" (PDF). Analize – Journal of Gender and Feminist Studies (12): 144. ISSN 2344-2352. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-26. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Joubin, Rebecca (2013). The Politics of Love: Sexuality, Gender, and Marriage in Syrian Television Drama. Lexington Books. pp. 163–171. ISBN 978-0-7391-8430-1.

- ^ Al-Zoubi, Suhail Mahmoud; Al-Zoubi, Samer Mahmoud (June 2022). "The Portrayal of Persons with Disabilities in Arabic Drama: A Literature Review". Research in Developmental Disabilities. 125: 3. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104221. PMID 35364425. S2CID 247828754.

- ^ AbuSalha, N. (2012). "The image of persons with disabilities in Arabic drama: A case study of the TV series 'Wara Al-Shams'" (PDF). Middle East University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-22. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moubayed, Sami (22 August 2018). "Hanna Mina: Doyen of the Syrian novel who highlighted the human condition". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Salamandra, Christa (2004). A New Old Damascus: Authenticity and Distinction in Urban Syria. Indiana University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-253-11041-1.

- ^ Salvatore, Armando (2001). Muslim Traditions and Modern Techniques of Power. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 248. ISBN 978-3-8258-4801-9.