ADNP syndrome: Difference between revisions

Add navbox templates |

Revised navboxes and external resources |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

{{Medical condition classification and resources |

|||

{{Medicine|state=collapsed}} |

|||

<!-- first row: classification --> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ICD11 = {{ICD11|LD90.Y}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ICD10 = {{ICD10|Q87.0}} |

|||

| OMIM = 615873 |

|||

| GARD = 12931 |

|||

<!-- second row: external resources --> |

|||

| Curlie = Health/Mental_Health/Disorders/Neurodevelopmental/Autism_Spectrum |

|||

}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Medical resources|ICD10=Q87.0|ICD11=LD90.Y|OMIM=615873}} |

|||

{{Pervasive developmental disorders}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Mental and behavioural disorders|selected=neurological}} |

|||

[[Category:Genetic diseases and disorders]] |

[[Category:Genetic diseases and disorders]] |

||

[[Category:Rare syndromes]] |

[[Category:Rare syndromes]] |

||

[[Category:Autism| ]] |

|||

[[Category:Developmental psychology]] |

|||

[[Category:Developmental neuroscience]] |

|||

[[Category:Autosomal dominant disorders]] |

[[Category:Autosomal dominant disorders]] |

||

Revision as of 12:23, 22 April 2023

| ADNP syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Helsmoortel Van der Aa syndrome, HVDAS |

| Specialty | Medical genetics, pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Delayed development, characteristic physical features, mild to moderate intellectual disability |

| Onset | Early childhood |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Mutation(s) in ADNP gene |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing |

| Treatment | Physical therapy, Occupational therapy, Speech therapy, Educational support |

| Frequency | Fewer than 50,000 people in the U.S. have this disease[1] |

ADNP syndrome, also known as Helsmoortel-Van der Aa syndrome (HVDAS), is a non-inherited neurodevelopmental disorder caused by mutations in the activity-dependent neuroprotector homeobox (ADNP) gene.[2][3]

The hallmark features of the syndrome are intellectual disability, global developmental delays, global motor planning delays, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autistic features. Although ADNP syndrome was only discovered in 2014, it is projected to be one of the most frequent single-gene causes of ASD.[4]

By June 2022, just over 275 children have been registered in the ADNP Kids Research Foundation Contact Registry.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of ADNP syndrome are variable, but the following are typical characteristics:[6][7][8]

- Severe speech and motor delay

- Mild-to-severe intellectual disability

- Characteristic facial features (prominent forehead, high hairline, wide and depressed nasal bridge, and short nose with full, upturned nasal tip)

- Features of autism spectrum disorder

- Hypotonia

Other commonly observed traits include:[6][7][8]

- Behavioral problems

- Sleep disturbance

- Brain abnormalities

- Seizures

- Feeding issues

- Gastrointestinal problems

- Visual dysfunction (hypermetropia, strabismus, cortical visual impairment)

- Musculoskeletal anomalies

- Endocrine issues including short stature and hormonal deficiencies

- Cardiac and urinary tract anomalies

- Hearing loss

- Early tooth eruption[9]

Almost all children with ADNP syndrome have speech delay. The average age for first words has been observed to be 30 months, with a range of 7 to 72 months.[2] One fifth (19%) of individuals studied did not develop any language skills.[2] Children with ADNP syndrome show some degree of intellectual disability. The degree can range from mild (roughly 1 in 8 children) to severe (roughly half of children). Toilet training is delayed in most children. Loss of previously acquired skills was reported in one fifth (19%) of people.[2]

The majority of children with ADNP syndrome have features of ASD, although with less severe socializing difficulties than other children with ASD.[10] During infant and toddler years, children are often reported to have an extraordinarily happy personality.[5]

Genetics

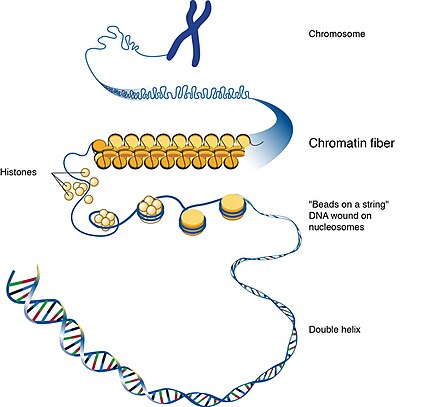

ADNP syndrome is caused by non-inherited (de novo) mutations in the ADNP gene.[1] Spanning about 40 kb of DNA, the ADNP gene maps to the chromosomal position chr20q13.13 in the human genome.[10] The protein produced from this gene helps control the activity (expression) of other genes through a process called chromatin remodeling. Chromatin is the network of DNA and protein that packages DNA into chromosomes. The structure of chromatin can be changed (remodeled) to alter how tightly DNA is packaged.[3]

By regulating gene expression, the ADNP protein is involved in many aspects of growth and development. It is particularly important for regulation of genes involved in normal brain development, and it likely controls the activity of genes that direct the development and function of other body systems.[3][7] These changes likely explain the intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, and other diverse signs and symptoms of ADNP syndrome.[3]

So far, only loss-of-function mutations such as stop-gain or frameshift mutations have been reported as unambiguously causative. Most, but not all mutations might give rise to a truncated protein.[10]

If neither parent is found to carry the change in the ADNP gene, the chance of having another child with ADNP syndrome is very low. However, there is a very small chance that some of the egg cells of the mother or some of the sperm cells of the father carry the change in the ADNP gene (see germline mosaicism). In this case, parents who are not found to carry the same ADNP change as their child on a blood test still have a very small chance of having another child with ADNP syndrome.[5]

ADNP has been associated with abnormalities in the autophagy pathway in schizophrenia.[11] As of 2023, its precise role in the autophagy process is under active investigation.[12][10]

Inverse comorbidity with cancer

The dual role of ADNP mutations in both neurodevelopment and cancer suggests that altering the core circuitry regulating differentiation has vastly divergent, developmental stage-dependent consequences, with equivalent mutations resulting in developmental delay or in cancer depending on whether or not they are present throughout development.[10] A thorough meta-analysis of brains from ASD individuals revealed gene expression dysregulation and biological pathway derailments in cancer. The opposite tendency of developing one condition or another (here ASD and cancer, respectively) within a population is called inverse comorbidity.[10]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ADNP syndrome is established through genetic testing to identify one or more pathogenic variants on the ADNP gene.

Molecular genetic testing in a child with developmental delay or an older individual with intellectual disability typically begins with chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA). If CMA is not diagnostic, the next step is typically either a multigene panel or exome sequencing. Single-gene testing (sequence analysis of ADNP, followed by gene-targeted deletion/duplication analysis) may be indicated in individuals exhibiting characteristic signs of ADNP syndrome.[6]

Treatment

Treatment is symptomatic. This may include speech, occupational, and physical therapy and specialized learning programs depending on individual needs.[6] Early behavioral interventions can help children with speech delays gain self-care, social, and language skills.

Treatment of neuropsychiatric features may also be needed. Nutritional support is sometimes needed. Treatment of the ophthalmologic and cardiac finding that may co-exist is also indicated.[6]

There is ongoing current research into treatments that may improve some features of the condition. A small study by researchers at the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at Mount Sinai Hospital suggests that low-dose ketamine may be effective in treating clinical symptoms in children diagnosed with ADNP syndrome.[13]

History

The gene was first cloned in 1998, and the syndrome was first described in 2014.[14] The first ADNP Syndrome Family Conference and Scientific Symposium was held on November 3, 2019 at the UCLA campus in Los Angeles, California.[15]

See also

- Angelman syndrome

- Fragile X syndrome

- Rett syndrome

- White Sutton syndrome

- Conditions comorbid to autism spectrum disorders

- Heritability of autism

References

- ^ a b "ADNP syndrome - About the Disease - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2023-04-18.

- ^ a b c d Van Dijck A, Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Cappuyns E, van der Werf IM, Mancini GM, Tzschach A, et al. (February 2019). "Clinical Presentation of a Complex Neurodevelopmental Disorder Caused by Mutations in ADNP". Biological Psychiatry. 85 (4): 287–297. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.02.1173. PMC 6139063. PMID 29724491.

- ^ a b c d "ADNP syndrome: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2022-09-07.

- ^ "ADNP Syndrome - Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD". rarediseases.org. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ a b c "ADNP syndrome (Helsmoortel-VanderAa syndrome (HVDAS))" (PDF). rarechromo.org. Unique. 2022. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ a b c d e Van Dijck A, Vandeweyer G, Kooy F (1993). "ADNP-Related Disorder". In Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE (eds.). GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 27054228.

- ^ a b c Pescosolido MF, Schwede M, Johnson Harrison A, Schmidt M, Gamsiz ED, Chen WS, et al. (September 2014). "Expansion of the clinical phenotype associated with mutations in activity-dependent neuroprotective protein". Journal of Medical Genetics. 51 (9): 587–589. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102444. PMC 4135390. PMID 25057125.

- ^ a b Vandeweyer G, Helsmoortel C, Van Dijck A, Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Coe BP, Bernier R, et al. (September 2014). "The transcriptional regulator ADNP links the BAF (SWI/SNF) complexes with autism". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 166C (3): 315–326. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31413. PMC 4195434. PMID 25169753.

- ^ Gozes I, Van Dijck A, Hacohen-Kleiman G, Grigg I, Karmon G, Giladi E, et al. (February 2017). "Premature primary tooth eruption in cognitive/motor-delayed ADNP-mutated children". Translational Psychiatry. 7 (2): e1043. doi:10.1038/tp.2017.27. PMC 5438031. PMID 28221363.

- ^ a b c d e f D'Incal CP, Van Rossem KE, De Man K, Konings A, Van Dijck A, Rizzuti L, et al. (March 2023). "Chromatin remodeler Activity-Dependent Neuroprotective Protein (ADNP) contributes to syndromic autism". Clinical Epigenetics. 15 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s13148-023-01450-8. PMC 10031977. PMID 36945042.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sragovich S, Merenlender-Wagner A, Gozes I (November 2017). "ADNP Plays a Key Role in Autophagy: From Autism to Schizophrenia and Alzheimer's Disease". BioEssays. 39 (11): 1700054. doi:10.1002/bies.201700054. PMID 28940660. S2CID 21961534.

- ^ Deng Z, Zhou X, Lu JH, Yue Z (December 2021). "Autophagy deficiency in neurodevelopmental disorders". Cell & Bioscience. 11 (1): 214. doi:10.1186/s13578-021-00726-x. PMC 8684077. PMID 34920755.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hospital, The Mount Sinai. "New study suggests ketamine may be an effective treatment for children with ADNP syndrome". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 2022-09-07.

- ^ Helsmoortel C, Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Coe BP, Vandeweyer G, Rooms L, van den Ende J, et al. (April 2014). "A SWI/SNF-related autism syndrome caused by de novo mutations in ADNP". Nature Genetics. 46 (4): 380–384. doi:10.1038/ng.2899. PMC 3990853. PMID 24531329.

- ^ "HIGHLIGHTS- ADNP Syndrome Family Conference". ADNP Kids Research Foundation. Retrieved 2023-04-19.