Kuru kingdom

Kuru Kingdom | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1200 BCE – c. 500 BCE | |||||||||||||

Kuru and other kingdoms in the Late Vedic period. | |||||||||||||

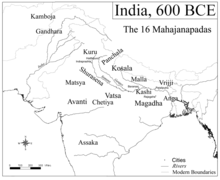

Kuru and other Mahajanapadas in the Post Vedic period. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Āsandīvat, later Hastinapura and Indraprastha | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Vedic Sanskrit | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Historical Vedic religion | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Raja (King or Chief) | |||||||||||||

• 12th–9th centuries BCE | Parikshit | ||||||||||||

• 12th–9th centuries BCE | Janamejaya | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||||||

• Established | c. 1200 BCE | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 500 BCE | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||||

Kuru (Template:Lang-sa) was a Vedic Indo-Aryan tribal union in northern Iron Age India, encompassing the modern-day states of Delhi, Haryana, Punjab and some parts of western Uttar Pradesh, which appeared in the Middle Vedic period[1][2] (c. 1200 – c. 900 BCE) and developed into the first recorded state-level society in the Indian subcontinent.[3][4][5]

The Kuru kingdom decisively changed the religious heritage of the early Vedic period, arranging their ritual hymns into collections called the Vedas, and developing new rituals which gained their position in Indian civilization as the Srauta rituals,[3] which contributed to the so-called "classical synthesis"[5] or "Hindu synthesis".[6] It became the dominant political and cultural center of the middle Vedic Period during the reigns of Parikshit and Janamejaya,[3] but declined in importance during the late Vedic period (c. 900 – c. 500 BCE) and had become "something of a backwater"[5] by the Mahajanapada period in the 5th century BCE. However, traditions and legends about the Kurus continued into the post-Vedic period, providing the basis for the Mahabharata epic.[3]

The main contemporary sources for understanding the Kuru kingdom are the Vedas, containing details of life during this period and allusions to historical persons and events.[3] The time-frame and geographical extent of the Kuru kingdom (as determined by philological study of the Vedic literature) suggest its correspondence with the archaeological Painted Grey Ware culture.[5]

History

The Kuru clan was formed in the Middle Vedic period[1][2] (c. 1200 – c. 900 BCE) as a result of the alliance and merger between the Bharata and other Puru clans, in the aftermath of the Battle of the Ten Kings.[3][7] With their center of power in the Kurukshetra region, the Kurus formed the first political center of the Vedic period, and were dominant roughly from 1200 to 800 BCE. The first Kuru capital was at Āsandīvat,[3] identified with modern Assandh in Haryana.[8][9] Later literature refers to Indraprastha (identified with modern Delhi) and Hastinapura as the main Kuru cities.[3]

The Kurus figure prominently in Vedic literature after the time of the Rigveda. The Kurus here appear as a branch of the early Indo-Aryans, ruling the Ganga-Yamuna Doab and modern Haryana. The focus in the later Vedic period shifted out of Punjab, into the Haryana and the Doab, and thus to the Kuru clan.[10]

This trend corresponds to the increasing number and size of Painted Grey Ware (PGW) settlements in the Haryana and Doab area. Archaeological surveys of the Kurukshetra District have a revealed a more complex (albeit not yet fully urbanized) three-tiered hierarchy for the period of period from 1000 to 600 BCE, suggesting a complex chiefdom or emerging early state, contrasting with the two-tiered settlement pattern (with some "modest central places", suggesting the existence of simple chiefdoms) in the rest of the Ganges Valley.[11] Although most PGW sites were small farming villages, several PGW sites emerged as relatively large settlements that can be characterized as towns; the largest of these were fortified by ditches or moats and embankments made of piled earth with wooden palisades, albeit smaller and simpler than the elaborate fortifications which emerged in large cities after 600 BCE.[12]

The Atharvaveda (XX.127) praises Parikshit, the "King of the Kurus", as the great ruler of a thriving, prosperous realm. Other late Vedic texts, such as the Shatapatha Brahmana, commemorate Parikshit's son Janamejaya as a great conqueror who performed the ashvamedha (horse-sacrifice).[13] These two Kuru kings played a decisive role in the consolidation of the Kuru state and the development of the srauta rituals, and they also appear as important figures in later legends and traditions (e.g., in the Mahabharata).[3]

The Kurus declined after being defeated by the non-Vedic Salva (or Salvi) tribe, and the center of Vedic culture shifted east, into the Panchala realm, in Uttar Pradesh (whose king Keśin Dālbhya was the nephew of the late Kuru king).[3] According to post-Vedic Sanskrit literature, the capital of the Kurus was later transferred to Kaushambi, in the lower Doab, after Hastinapur was destroyed by floods[1] as well as because of upheavals in the Kuru family itself.[14][15][note 1] In the post Vedic period (by the 6th century BCE), the Kuru dynasty evolved into Kuru and Vatsa janapadas, ruling over Upper Doab/Delhi/Haryana and lower Doab, respectively. The Vatsa branch of the Kuru dynasty further divided into branches at Kaushambi and at Mathura.[17]

Society

The tribes that consolidated into the Kuru Kingdom or 'Kuru Pradesh' were largely semi-nomadic, pastoral tribes. However, as settlement shifted into the western Ganges Plain, settled farming of rice and barley became more important. Vedic literature of this time period indicates the growth of surplus production and the emergence of specialized artisans and craftsmen. Iron was first mentioned as śyāma āyas (श्याम आयस, literally "black metal") in the Atharvaveda, a text of this era. Another important development was the fourfold varna (class) system, which replaced the twofold system of arya and dasa from the Rigvedic times. The Brahmin priesthood and Kshatriya aristocracy, who dominated the arya commoners (now called vaishyas) and the dasa labourers (now called shudras), were designated as separate classes.[3][19]

Kuru kings ruled with the assistance of a rudimentary administration, including purohita (priest), village headman, army chief, food distributor, emissary, herald and spies. They extracted mandatory tribute (bali) from their population of commoners as well as from weaker neighboring tribes. They led frequent raids and conquests against their neighbors, especially to the east and south. To aid in governing, the kings and their Brahmin priests arranged Vedic hymns into collections and developed a new set of rituals (the now orthodox Srauta rituals) to uphold social order and strengthen the class hierarchy. High-ranking nobles could perform very elaborate sacrifices, and many poojas (rituals) primarily exalted the status of the king over his people. The ashvamedha or horse sacrifice was a way for a powerful king to assert his domination in northern India.[3]

In epic literature

The epic poem, the Mahabharata, tells of a conflict between two branches of the reigning Kuru clan possibly around 1000 BCE. However, archaeology has not furnished conclusive proof as to whether the specific events described have any historical basis. The existing text of the Mahabharata went through many layers of development and mostly belongs to the period between c. 400 BCE and 400 CE.[21] Within the frame story of the Mahabharata, the historical kings Parikshit and Janamejaya are featured significantly as scions of the Kuru clan.[3]

A historical Kuru King named Dhritarashtra Vaichitravirya is mentioned in the Kathaka Samhita of the Yajurveda (c. 1200–900 BCE) as a descendant of the Rigvedic-era king Sudas. His cattle were reportedly destroyed as a result of conflict with the vratya ascetics; however, this Vedic mention does not provide corroboration for the accuracy of the Mahabharata's account of his reign.[22][23]

Kuru family tree in Mahabharata

This shows the line of royal and family succession, not necessarily the parentage. See the notes below for detail.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Key to Symbols

Notes

- a: Shantanu was a king of the Kuru dynasty or kingdom, and was some generations removed from any ancestor called Kuru. His marriage to Ganga preceded his marriage to Satyavati.

- b: Pandu and Dhritarashtra were fathered by Vyasa in the niyoga tradition after Vichitravirya's death. Dhritarashtra, Pandu and Vidura were the sons of Vyasa with Ambika, Ambalika and a maid servant respectively.

- c: Karna was born to Kunti through her invocation of Surya, before her marriage to Pandu.

- d: Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula and Sahadeva were acknowledged sons of Pandu but were begotten by the invocation by Kunti and Madri of various deities. They all married Draupadi (not shown in tree).

- e: Duryodhana and his siblings were born at the same time, and they were of the same generation as their Pandava cousins.

- f : Although the succession after the Pandavas was through the descendants of Arjuna and Subhadra, it was Yudhishthira and Draupadi who occupied the throne of Hastinapura after the great battle.

The birth order of siblings is correctly shown in the family tree (from left to right), except for Vyasa and Bhishma whose birth order is not described, and Vichitravirya and Chitrangada who were born after them. The fact that Ambika and Ambalika are sisters is not shown in the family tree. The birth of Duryodhana took place after the birth of Karna, Yudhishthira and Bhima, but before the birth of the remaining Pandava brothers.

Some siblings of the characters shown here have been left out for clarity; this includes Vidura, half-brother to Dhritarashtra and Pandu.

See also

- Kuru related

- Other Mahabharta related

- Modern archaeology of Vedic era

- Present day regions

Notes

- ^ The flooding of Hastinapura and the transfer of the capital to Kaushambi is only mentioned in semi-legendary accounts dating to the post-Vedic era, e.g., Puranas and Mahabharata, whereas Vedic-era texts only mention the invasion of Kurukshetra by the Salva tribe as the cause for the decline of the Kurus.[16]

References

- ^ a b c Pletcher 2010, p. 63.

- ^ a b Witzel 1995, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Witzel 1995.

- ^ B. Kölver, ed. (1997). Recht, Staat und Verwaltung im klassischen Indien [Law, State and Administration in Classical India] (in German). München: R. Oldenbourg. pp. 27–52.

- ^ a b c d Samuel 2010.

- ^ Hiltebeitel 2002.

- ^ National Council of Educational Research and Training, History Text Book, Part 1, India

- ^ Prāci-jyotī: Digest of Indological Studies. Kurukshetra University. 1 January 1967.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (1 January 2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. ISBN 9780143414216.

- ^ Steven G. Darian (2001). The Ganges In Myth And History. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 63. ISBN 9788120817579.

- ^ Bellah, Robert N. Religion in Human Evolution (Harvard University Press, 2011), p. 492; citing Erdosy, George. "The prelude to urbanization: ethnicity and the rise of Late Vedic chiefdoms," in The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States, ed. F. R. Allchin (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 75-98

- ^ James Heitzman, The City in South Asia (Routledge, 2008), pp.12-13

- ^ Raychaudhuri, H. C. (1972). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty, Calcutta:University of Calcutta, pp.11-46

- ^ "About the District". kaushambhi.nic.in. District Kaushambi, Uttar Pradesh, India. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "History of Art: Visual History of the World". www.all-art.org. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Witzel 1990, p. [page needed].

- ^ "Political History of Uttar Pradesh". Govt of Uttar Pradesh, official website. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012.

- ^ Śrīrāma Goyala (1994). The Coinage of Ancient India. Kusumanjali Prakashan.

- ^ Sharma, Ram Sharan (1990), Śūdras in Ancient India: A Social History of the Lower Order Down to Circa A.D. 600 (Third ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0706-8

- ^ "INDIA, Pre-Mauryan (Ganges Valley). Kurus (Kurukshetras)". CNG Coins.

- ^ Singh, U. (2009), A History of Ancient and Mediaeval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Delhi: Longman, p. 18-21, ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9

- ^ Witzel 1995, p. 17 footnote 115.

- ^ Witzel 1990, p. 9.

Sources

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2002), Hinduism. In: Joseph Kitagawa, "The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture", Routledge, ISBN 9781136875977

- Pletcher, Kenneth (2010), The History of India, The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 9781615301225

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Witzel, Michael (1990), "On Indian Historical Writing" (PDF), Journal of the Japanese Association for South Asian Studies, 2: 1–57

- Witzel, Michael (1995), "Early Sanskritization: Origin and Development of the Kuru state" (PDF), EJVS, 1 (4), archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007

Further reading

External links

- Kuru Kingdom

- Mahabharata of Krishna Dwaipayana Vyasa, translated to English by Kisari Mohan Ganguli

- The Kuru race in Sri Lanka - Web site of Kshatriya Maha Sabha

- Coins of Kuru janapada