Kresy

| Kresy Wschodnie | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Second Polish Republic | |

In the 1939 German-Soviet Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact the Eastern Borderlands (grey) were annexed directly into the Soviet Union. The Soviet gains east of the Curzon line devised in 1919 were confirmed (with minor adjustments in the areas around Białystok and Przemyśl) by the Western Allies at the Tehran Conference, the Yalta conference and the Potsdam conference. In 1945 most of Germany's territory east of the Oder–Neisse line (pink) was ceded to what remained of Poland (white), both of which would compose the newly created People's Republic of Poland | |

| Historical region | |

| Period | 1919–1939; 1945 |

| Area | Territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union in the Invasion of Poland of 1939 |

| Today part of | |

| Territorial evolution of Poland in the 20th century |

|---|

Eastern Borderlands[1] (Template:Lang-pl) or simply Borderlands (Template:Lang-pl, Polish pronunciation: [ˈkrɛsɨ]) was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic with a Polish minority,[2] it amounted to nearly half of the territory of interwar Poland. Historically situated in the eastern Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, following the 18th-century foreign partitions it was divided between the Empires of Russia and Austria-Hungary, and ceded to Poland in 1921 after the Treaty of Riga. As a result of the post-World War II border changes, all of the territory was ceded to the USSR, and none of it is in modern Poland.

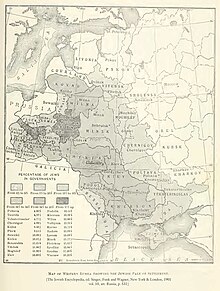

The Polish plural term Kresy corresponds to the Russian okrainy (Template:Lang-ru), meaning "the border regions".[3] During the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Kresy only referred to the borderlands of the Kingdom of Poland and not the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[4] Kresy is also largely co-terminous with the northern areas of the Pale of Settlement, a scheme devised by Catherine II of Russia to limit Jews from settling in the homogenously Christian Orthodox core of the Russian Empire, such as Moscow and Saint Petersburg. The Pale was established after the Second Partition of Poland and lasted until the Russian Revolution in 1917, when the Russian Empire ceased to exist. In the aftermath of the Polish wars against Ukraine, Lithuania and Soviet Russia, the latter of which was ended by the Treaty of Riga, large parts of the Austrian and Russian partitions became part of Poland. As many as 12 million inhabitants lived in the Eastern Borderlands, but ethnic Poles only were a third of that population, with another third being Ukrainian.[4][5] Most small towns in the Borderlands were shtetls.[5]

Administratively, the Eastern Borderlands territory was composed of Lwów, Nowogródek, Polesie, Stanisławów, Tarnopol, Wilno, Wołyń, and Białystok voivodeships (provinces). Today, all these regions are divided between Western Ukraine, Western Belarus, and south-eastern Lithuania, with the major cities of Lviv, Vilnius, and Grodno no longer in Poland. During the Second Polish Republic, the Eastern Borderlands denoted the lands beyond the Curzon Line proposed after World War I in December 1919 by the British Foreign Office as the eastern border of the re-emerging sovereign Polish Republic, after over a century of partition. In September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland and follow-up invasion by Soviet Union, in accordance with Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact all Eastern Borderlands territories were incorporated into the Soviet republics of Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania, often by means of terror.[6]

Soviet territorial annexations during World War II were later ratified by the Allies at the Conferences of Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam and most of Poles here were expelled after the end of World War II in Europe. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, there was no change to the post-World War II borders. Despite the former provinces of the Eastern Borderlands no longer being part of Poland, a Polish minority remains.

Etymology

The Polish word kresy ("borderlands") is the plural form of the word kres meaning 'edge'. According to Zbigniew Gołąb, it is "a medieval borrowing from the German word Kreis", which in the Middle Ages meant Kreislinie, Umkreis, Landeskreis ("borderline, delineation or circumscribed territory").[7] Samuel Linde in his Dictionary of the Polish Language gives a different etymology of the term. According to him, kresy meant the borderline between Poland and the Crimean Khanate, in the region of the lower Dnieper. The term kresy appeared for the first time in literature in Wincenty Pol poems, "Mohort" (1854) and "Pieśń o ziemi naszej". Pol claimed that Kresy was the line between the Dniester and Dnieper rivers, neighbouring the Tatar borderland.[8] Coincidentally in relation to Jewish settlement in the macro region, the notion of the pale is an archaic English term derived from the Latin word palus, (which in Polish exists as pal and also means a stake), extended in this instance to mean the area enclosed by a fence or boundary.[9]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the meaning of the term expanded to include the lands of the former eastern provinces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, east of the Lwów–Wilno line. In the Second Polish Republic, Kresy equated to historically Polish settled lands to the east of the notional Curzon line. Currently, the term applies to all the eastern lands of the Second Polish Republic that are no longer within the frontiers of modern Poland, together with lands further east, that had been integral to the Commonwealth before 1772, and where Polish communities continue to exist.[10]

History

Polish eastern settlements date back to the dawn of Poland as a state. In 1018, King Bolesław I the Brave invaded Kievan Rus' (see Bolesław I's intervention in the Kievan succession crisis, 1018), capturing Kyiv, and annexing the Cherven Cities. In 1340, Red Ruthenia came under Polish control, which intensified defensive Polish settlement and the introduction of Catholicism. After the Union of Lublin 1569, more Polish settlers moved into the eastern borderlands of the vast Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Most of them came from the Polish provinces of Mazovia and Lesser Poland. They had moved gradually eastwards settling in sparsely populated areas, inhabited by earlier inhabitants such as Lithuanians and Ruthenians. Moreover, the indigenous upper classes of Kresy accepted Polish religion, culture and language, resulting in their assimilation and Polonization.

The Partitions of Poland

The year 1772 marked the first partition of the Commonwealth of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (see Partitions of Poland). By 1795, the whole eastern half of the state had been annexed by the Russian Empire in concert with the Habsburgs and Prussia's Hohenzollerns. The dramatic westward expansion of the Russian Empire through the annexation of Polish-Lithuanian territory substantially increased the new "Russian" Jewish population. Kresy and the superimposed Pale, in the former Polish and Lithuanian territories, had a Jewish population of over five million, and represented the largest community (40%) of the world Jewish population at that time.

From the Polish perspective, the lands came to be called the "Stolen Lands". Even though Poles were a minority in those areas, owing to forced depopulation, the "Stolen Lands" remained an integral part of Polish national identity, with Polish cultural centres and seats of learning in Vilnius University, Jan Kazimierz University and Krzemieniec Lyceum among many others. Since many local educated inhabitants had actively participated in Polish–Lithuanian national insurgencies (November Uprising, January Uprising), the Russian authorities resorted to intensified persecution, confiscations of property and land, penal deportation to Siberia, and the systematic attempt at Russification of Poles and their traditional culture and institutions.

The Pale of Settlement

From the Russian perspective the "Pale of Settlement" included all of Belarus, Lithuania and Moldova, much of present-day Ukraine, parts of eastern Latvia, eastern Poland, and some parts of western Russia, generally corresponding to the Kresy macroregion and the modern-day western border of Russia. It extended from the eastern pale, or demarcation line, to the Russian border with the Kingdom of Prussia (later the German Empire) and Austria-Hungary. It also comprised about 20% of the territory of European Russia and largely corresponded to historical lands of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Cossack Hetmanate, and the Ottoman Empire (with Crimean Khanate).

The area included in the Pale, with its large Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholic and Jewish populations, was acquired through a series of military conquests and diplomatic manoeuvres, between 1654 and 1815. While the religious nature of the edicts creating the Pale is clear: conversion to Russian Orthodoxy, the state religion, released individuals from the strictures - historians argue that the motivations for its creation and maintenance were primarily economic and nationalistic in nature.[11]

Economic decline of Kresy

The Russian Empire had abandoned Kresy to decline as a vast rural backwater after the original Polish–Lithuanian landowners had been disposed of in the wake of insurrections and the Abolition of serfdom in Poland in 1864. The devastation of country estates put a halt to large scale economic activity which had depended on agriculture, forestry, brewing and small scale industries. Paradoxically, the Southern Kresy (present-day Ukraine) was famous for its fertile soil and was known as the "bread basket of Europe". Towards the end of the 19th century, the decline was so acute that trade and food supplies became problematic and large scale emigration from towns and villages began as Jewish communities, in particular, began heading West, to Europe and the United States. By the time of a newly resurgent Polish state, the provinces had been additionally disadvantaged by having the lowest literacy levels in the country, since education had not been compulsory during Russian rule.[12][13][14] The regions had suffered a legacy of decades of neglect and underinvestment so were generally less economically developed than the western parts of interwar Poland.

Between the World Wars

The years 1918–1921 were especially turbulent for Kresy, due to the resurgence of the Polish nation-state and the formation of new borders. At that time, Poland had fought three wars to establish its eastern frontier: with Ukraine, Lithuania and Soviet Russia. In all three conflicts, Poland made territorial conquests, and as a result, it seized territories east of the Curzon line that were previously conquered by Russia, in addition to the land formerly part of the Austrian Galicia. The Kresy was the most war-devastated area in the whole of interwar Poland.[15] The region later formed the eastern provinces of the Second Polish Republic.

Territories included in the Kresy during the interbellum period comprised the eastern parts of the Voivodeships of Lwów and Białystok and the whole of the Nowogródek, Polesie, Stanisławów, Tarnopol, Wilno, Wołyń Voivodeships. The Polish government undertook an active policy of Polonizing the Kresy to alter its ethnic profile in favour of the Poles.[15] One of the ways to do so was through the Osadnik colonists.[15] These military colonists were one of the most "emotionalized" parts of the Polish government's policy in the Kresy and elicited opposition from the locals.[16] The German historian Bernhard Chiari said that the Kresy were "the poorhouse of Poland", while the Yad Vashem historian Leonid Rein even wrote that "it would not be a great exaggeration to say it was the poor-house of the whole of Europe."[17] This led to frequent conflicts with Ukrainian nationalists in the southeastern part of Kresy, which led to the pacification of Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia.

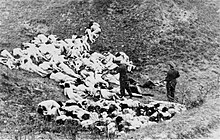

Numerous Polish communities continued to live beyond the eastern border of the Second Polish Republic, especially around Minsk, Zhytomyr and Berdychiv. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Soviet authorities created two Polish National Districts in Belarus and Ukraine, but during the Polish Operation of the NKVD, most of the Poles in those areas were murdered, while those remaining were forcibly resettled in Kazakhstan (see also Poles in the Soviet Union).

During and after World War II

As a consequence of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, on 17 September 1939, the Kresy territories were annexed by the Soviet Union (see Soviet invasion of Poland), and a significant part of the ethnic Polish population of Kresy was deported to other areas of the Soviet Union including Siberia and Kazakhstan.[18] The new border between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union was re-designated by the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty, signed on 29 September 1939. After the elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus, communist governments for Western Ukraine and Western Belarus were formed and immediately announced their intention of joining their respective republics to the Soviet Union (see also Territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union). After the German invasion of the USSR, the southeastern part of Kresy was absorbed into Greater Germany's General Government, whereas the rest was integrated with the Reichskommissariats Ostland and Ukraine. In 1943–1944, units of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, with the help of Ukrainian peasants, carried out mass exterminations of Poles living in southeastern Kresy (see Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia).

In January 1944, Soviet troops had reached the former Polish–Soviet border, and by the end of July 1944, they again re-annexed the whole territory that had been taken by the USSR in September 1939 into their control. During the Tehran Conference in 1943, a new Soviet-Polish border was established, in effect sanctioning most of the Soviet territorial acquisitions of September 1939 (except for some areas around Białystok and Przemyśl), ignoring protests from the Polish government-in-exile in London. The Potsdam Conference, via substantive recognition of the pro-Soviet Polish Committee of National Liberation, implicitly consented to the deportation of Polish people from Kresy (see Polish population transfers (1944–1946)). Most Polish inhabitants of Kresy were ordered by the Soviets to migrate west to Germany's former eastern provinces, newly emptied of their German population and renamed as the "Recovered Territories" of the Polish People's Republic, based on Polish medieval settlement of the areas. Poles from the southern Kresy (now Ukraine) were forced to settle mainly in Silesia, while those from the north (Belarus and Lithuania) moved to Pomerania and Masuria. Polish residents of Lwów settled not only in Wrocław, but also in Gliwice and in Bytom. Those cities had not been destroyed during the war. They were relatively closer to the new eastern border of Poland, which could become significant in case of a sudden hoped for a return to the East.[19]

Frequently, whole Kresy villages and towns were deported in a single rail transport to new locations in the west. For instance, the village of Biała, near Chojnów, is still divided into two parts: Lower Biała and Upper Biała. Lower Biała was settled by people who used to live in a Bieszczady village of Polana near Ustrzyki Dolne (this area belonged to the Soviet Union until 1951: see 1951 Polish–Soviet territorial exchange), while inhabitants of the village Pyszkowce near Buczacz moved to Upper Biała. Every year in September, Biała is the scene of an annual festival called Kresowiana.[20] In Szczecin and Polish West Pomerania, in the immediate postwar period, one-third of Polish settlers were either people from Kresy or Sybiraks.[21] In 1948, people born in the Eastern Borderlands made up 47.5% of the population of Opole, 44.7% of Baborów, 47.5% of Wołczyn, 42.1% of Głubczyce, 40.1% of Lewin Brzeski, and 32.6% of Brzeg. In 2011, people with Kresy background made up 25% of the population of the Opole Voivodeship.[22] The town of Jasień was settled by people from the area of Ternopil in late 1945 and early 1946,[23] while Poles from Borschiv moved to Trzcińsko-Zdrój and Chojna.[24] The situation was completely different in Wschowa and its county. In 1945–1948, more than 8,000 people moved there. They came from different areas of the Kresy — Ashmyany, Stanislawow, Równe, Lwów, Brody, Dzyatlava District, and Ternopil.[25]

Altogether, between 1944 and 1946, more than a million Poles from the Kresy were moved to the Recovered Territories, including 150,000 from the area of Wilno, 226,300 from Polesia, 133,900 from Volhynia, 5,000 from Northern Bukovina, and 618,200 from Eastern Galicia.[26] The so-called First Repatriation of Poles (1944–1946) was carried out in a chaotic, disorganized way. People had to spend weeks, even months at railroad stations, waiting for transport. During that time, they were robbed of their belongings by either locals, Soviet soldiers or Soviet rail workers. For lack of railroad cars, in Lithuania at some point the "one-suitcase policy" was introduced, which meant that Poles had to leave behind all their belongings. They travelled in freight or open wagons, and the journeys were long and dangerous, as there was no protection from the military or the police.[19] In the years 1955–1959, the second mass repatriation of Poles from Kresy took place. As a result, in the years 1945–1960, over 2 million Polish people left Kresy. About 1-2 million more remained in the Kresy after 1960 (especially in the territories of the Lithuanian SSR and the Byelorussian SSR). Even today, Poles constitute the majority of inhabitants in many regions in the Grodno and Vilnius regions. Poles appear in the most recent national censuses as follows - Lithuania 183,000 (2021) ; Belarus 288,000 (2019) ; Ukraine 144,000 (2001) - the Belarus and Ukraine numbers firmly disputed in Poland.

In the immediate postwar period, Polish Communists, who ceded the Eastern Borderlands to the Soviet Union, were universally regarded as traitors, and Władysław Gomułka, First Secretary of the Polish Workers' Party, was fully aware of it. People who moved from the East to the Recovered Territories talked amongst themselves about their return to Lwów and other eastern locations, and the German return to Silesia, as a result of World War III, in which Western Allies would defeat the Soviets. One of the adages of the postwar period was: "Just one atom bomb, and we will be back in Lwów again. Just second one is small but strong and we will be back in Wilno again." ("Jedna bomba atomowa i wrócimy znów do Lwowa. Druga mała, ale silna i wrócimy znów do Wilna").[27][28] Polish settlers in former German areas were insecure about their future there until the 1970s (see Kniefall von Warschau). Eastern settlers did not feel at home in Lower Silesia, and as a result, they did not care about the machinery, households and farms abandoned by Germans. Lubomierz in 1945 was in good condition, but in the following years, Polish settlers from the area of Chortkiv in Podolia let it run down and become a ruin. The Germans were aware of it. In 1959, German sources wrote that Lower Silesia had been ruined by the Poles. Zdzisław Mach, a sociologist from the Jagiellonian University, explains that when Poles were forced to resettle in the West, which they resented, they had to leave the land they considered sacred and move to areas inhabited by the enemy. In addition, Communist authorities did not initially invest in the Recovered Territories because, like the settlers, for a long time they were unsure about the future of these lands. As Mach says, people in Western Poland for years lived "on their suitcases", with all their belongings packed in case of return to the East.[29]

Interwar population

The population of Kresy was multi-ethnic, primarily comprising Poles, Ukrainians, Jews and Belarusians. According to official Polish statistics from the interwar period, Poles formed the largest linguistic group in these regions, and were demographically the largest ethnic group in the cities. Other national minorities included Lithuanians and Karaites (in the north), Jews (scattered in cities and towns across the area), Czechs and Germans (in Volhynia and East Galicia), Armenians and Hungarians (in Lviv) and also Russians and Tatars.[30]

The proportions of different native languages in each voivodeship in 1931, according to the Polish census of 1931, were as follows:

- Lwów Voivodeship; 58% Polish, 34% Ukrainian, 8% Yiddish

- Nowogródek Voivodeship; 53% Polish, 39% Belarusian, 7% Yiddish, 1% Russian

- Polesie Voivodeship; 63% "Other" or Tutejszy (Polesian and other dialects), 14% Polish, 10% Yiddish, 6% Belarusian, 5% Ukrainian

- Stanisławów Voivodeship; 69% Ukrainian, 23% Polish, 7% Yiddish, 1% German

- Tarnopol Voivodeship; 50% Polish, 45% Ukrainian, 5% Yiddish

- Wilno Voivodeship; 60% Polish, 23% Belarusian, 8% Yiddish, 3% Russian, 8% Other (including Lithuanian)

- Wołyń Voivodeship; 68% Ukrainian, 17% Polish, 10% Yiddish, 2% German, 1% Russian, 2% Other

- Białystok Voivodeship; 71% Polish, 13% Belarusian, 11% Yiddish, 3% Russian, 2% Other[31]

In addition to ethnic Poles in former eastern Poland, there were also large Polish communities in the USSR and in the Baltic states. Polish population east of the Curzon Line before World War II can be estimated by adding together figures for Former Eastern Poland and for pre-1939 Soviet Union:

| 1. Interwar Poland | Polish mother tongue (of whom Roman Catholics) | Source (census) | Today part of: |

|---|---|---|---|

| South-Eastern Poland | 2,249,703 (1,765,765)[32] | 1931 Polish census[33] | |

| North-Eastern Poland | 1,663,888 (1,358,029)[34][35] | 1931 Polish census | |

| 2. Interwar USSR | Ethnic Poles according to official census | Source (census) | Today part of: |

| Soviet Ukraine | 476,435 | 1926 Soviet census | |

| Soviet Belarus | 97,498 | 1926 Soviet census | |

| Soviet Russia | 197,827 | 1926 Soviet census | |

| rest of the USSR | 10,574 | 1926 Soviet census | |

| 3. Interwar Baltic states | Ethnic Poles according to official census | Source (census) | Today part of: |

| Lithuania | 65,599 [Note 1] | 1923 Lithuanian census | |

| Latvia | 59,374 | 1930 Latvian census[36] | |

| Estonia | 1,608 | 1934 Estonian census | |

| TOTAL (1., 2., 3.) | 4 to 5 million ethnic Poles |

- ^ Polish sources estimated, based on the percentage of votes for Polish parties in the 1923 Lithuanian parliamentary election, that the real number of ethnic Poles in interwar Lithuania in 1923 was 202,026.

Largest cities and towns

In 1931, according to the Polish National Census, the ten largest cities in Polish Eastern Borderlands were: Lwów (pop. 312,200), Wilno (pop. 195,100), Stanisławów (pop. 60,000), Grodno (pop. 49,700), Brześć nad Bugiem (pop. 48,400), Borysław (pop. 41,500), Równe (pop. 40,600), Tarnopol (pop. 35,600), Łuck (pop. 35,600) and Kołomyja (pop. 33,800).

In addition, Daugavpils (pop. 43,200 in 1930) in inter-war Latvia was also a major Polish community with 21% ethnic Polish inhabitants.

| City | Pop. | Polish | Yiddish & Hebrew | German | Ukrainian & Ruthenian | Belarusian | Russian | Lithuanian | Other | Today part of: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lwów | 312,231 | 63.5% (198,212) | 24.1% (75,316) | 0.8% (2,448) | 11.3% (35,137) | 0% (24) | 0.1% (462) | 0% (6) | 0.2% (626) | |

| Wilno | 195,071 | 65.9% (128,628) | 28% (54,596) | 0.3% (561) | 0.1% (213) | 0.9% (1,737) | 3.8% (7,372) | 0.8% (1,579) | 0.2% (385) | |

| Stanisławów | 59,960 | 43.7% (26,187) | 38.3% (22,944) | 2.2% (1,332) | 15.6% (9,357) | 0% (3) | 0.1% (50) | 0% (1) | 0.1% (86) | |

| Grodno | 49,669 | 47.2% (23,458) | 42.1% (20,931) | 0.2% (99) | 0.2% (83) | 2.5% (1,261) | 7.5% (3,730) | 0% (22) | 0.2% (85) | |

| Brześć | 48,385 | 42.6% (20,595) | 44.1% (21,315) | 0% (24) | 0.8% (393) | 7.1% (3,434) | 5.3% (2,575) | 0% (1) | 0.1% (48) | |

| Daugavpils | 43,226 | 20.8% (9,007) | 26.9% (11,636) | - | - | 2.3% (1,006) | 19.5% (8,425) | - | 30.4% (13,152) | |

| Borysław | 41,496 | 55.3% (22,967) | 25.4% (10,538) | 0.5% (209) | 18.5% (7,686) | 0% (4) | 0.1% (37) | 0% (2) | 0.1% (53) | |

| Równe | 40,612 | 27.5% (11,173) | 55.5% (22,557) | 0.8% (327) | 7.9% (3,194) | 0.1% (58) | 6.9% (2,792) | 0% (4) | 1.2% (507) | |

| Tarnopol | 35,644 | 77.7% (27,712) | 14% (5,002) | 0% (14) | 8.1% (2,896) | 0% (2) | 0% (6) | 0% (0) | 0% (12) | |

| Łuck | 35,554 | 31.9% (11,326) | 48.6% (17,267) | 2.3% (813) | 9.3% (3,305) | 0.1% (36) | 6.4% (2,284) | 0% (1) | 1.5% (522) | |

| Kołomyja | 33,788 | 65% (21,969) | 20.1% (6,798) | 3.6% (1,220) | 11.1% (3,742) | 0% (0) | 0% (6) | 0% (2) | 0.2% (51) | |

| Drohobycz | 32,261 | 58.4% (18,840) | 24.8% (7,987) | 0.4% (120) | 16.3% (5,243) | 0% (13) | 0.1% (21) | 0% (0) | 0.1% (37) | |

| Pińsk | 31,912 | 23% (7,346) | 63.2% (20,181) | 0.1% (45) | 0.3% (82) | 4.3% (1,373) | 9% (2,866) | 0% (2) | 0.1% (17) | |

| Stryj | 30,491 | 42.3% (12,897) | 31.4% (9,561) | 1.6% (501) | 24.6% (7,510) | 0% (0) | 0% (10) | 0% (0) | 0% (12) | |

| Kowel | 27,677 | 37.2% (10,295) | 46.2% (12,786) | 0.2% (50) | 9% (2,489) | 0.1% (27) | 7.1% (1,954) | 0% (1) | 0.3% (75) | |

| Włodzimierz | 24,591 | 39.1% (9,616) | 43.1% (10,611) | 0.6% (138) | 14% (3,446) | 0.1% (18) | 2.9% (724) | 0% (0) | 0.2% (38) | |

| Baranowicze | 22,818 | 42.8% (9,758) | 41.3% (9,423) | 0.1% (25) | 0.2% (50) | 11.1% (2,537) | 4.4% (1,006) | 0% (1) | 0.1% (18) | |

| Sambor | 21,923 | 61.9% (13,575) | 24.3% (5,325) | 0.1% (28) | 13.2% (2,902) | 0% (4) | 0% (4) | 0% (0) | 0.4% (85) | |

| Krzemieniec | 19,877 | 15.6% (3,108) | 36.4% (7,245) | 0.1% (23) | 42.4% (8,430) | 0% (6) | 4.4% (883) | 0% (2) | 0.9% (180) | |

| Lida | 19,326 | 63.3% (12,239) | 32.6% (6,300) | 0% (5) | 0.1% (28) | 2.1% (414) | 1.7% (328) | 0% (2) | 0.1% (10) | |

| Czortków | 19,038 | 55.2% (10,504) | 25.5% (4,860) | 0.1% (11) | 19.1% (3,633) | 0% (0) | 0.1% (17) | 0% (0) | 0.1% (13) | |

| Brody | 17,905 | 44.9% (8,031) | 35% (6,266) | 0.2% (37) | 19.8% (3,548) | 0% (5) | 0.1% (9) | 0% (0) | 0.1% (9) | |

| Słonim | 16,251 | 52% (8,452) | 41.1% (6,683) | 0.1% (9) | 0.3% (45) | 4% (656) | 2.3% (369) | 0% (2) | 0.2% (35) | |

| Wołkowysk | 15,027 | 49.6% (7,448) | 38.8% (5,827) | 0% (7) | 0.1% (10) | 6.9% (1,038) | 4.6% (689) | 0% (3) | 0% (5) |

Polish minority after World War II

Despite the expulsion of most of ethnic Poles from the Soviet Union between 1944 and 1958, the Soviet census of 1959 still counted around 1.5 million ethnic Poles remaining in the USSR:

| Republic of the USSR | Ethnic Poles in 1959 census |

|---|---|

| Belarusian SSR | 538,881 |

| Ukrainian SSR | 363,297 |

| Lithuanian SSR | 230,107 |

| Latvian SSR | 59,774 |

| Estonian SSR | 2,256 |

| rest of the USSR | 185,967 |

| TOTAL | 1,380,282 |

According to a more recent census, there were about 295,000 Poles in Belarus in 2009 (3.1% of the Belarus population).[38]

Notable people

A number of influential figures in Polish history were born in the area of kresy (note: the redirected list does not include Poles born in the cities of Lwów (Lviv), and Wilno (Vilnius) - see List of Leopolitans, List of people from Vilnius). The family of former President of Poland, Bronisław Komorowski, allegedly hails from northern Lithuania.[39] The mother of Bogdan Zdrojewski, Minister of Culture and National Heritage is from Boryslav,[40] and the father of former First Lady Jolanta Kwaśniewska was born in Wołyń, where his sister was murdered in 1943 by the Ukrainian nationalists.[41]

Cradle of Polish culture

Since some of the most distinguished names of Polish literature and music were born in Kresy, e.g. Mikołaj Rej, Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Karol Szymanowski or Czesław Miłosz, Eastern Borderlands have featured repeatedly in the Polish Literary canon. Mickiewicz's Pan Tadeusz begins with the Polish language invocation, "O Lithuania, my fatherland, thou art like good health...." Other notable works located in Kresy, are Nad Niemnem, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, With Fire and Sword, Fire in the Steppe. In Communist Poland, all Kresy-related topics, such as Poland's eastern centuries old heritage, including ecclesiastical architecture, country houses and stately homes down to the Massacres of Poles in Wołyń were banned from publication for Soviet propaganda reasons, because these lands now belonged to the Soviet Union. In official documents, people born in the Eastern Borderlands were declared as born in the Soviet Union, and very few Kresy-themed books or films were passed by the state censor at that time.[42] One of the exceptions was the immensely popular comedy trilogy by Sylwester Chęciński (Sami swoi from 1967, Nie ma mocnych from 1974, and Kochaj albo rzuć from 1977). The trilogy tells the story of two quarreling families, who after the end of the Second World War were resettled from current Western Ukraine to Lower Silesia, after Poland was shifted westwards.

After the collapse of the Communist system, the old Kresy returned as a Polish cultural theme in the form of historical polemics. Numerous books and albums were published about the Eastern Borderlands, frequently with original photos from the prewar era. Examples of such publications include:

- Roman Aftanazy. Dzieje rezydencji na dawnych kresach Rzeczypospolitej. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Ossolineum, 1991–1997. History of Residences in Poland's Former Eastern Borderlands, (1991–1997), listing and describing in a monumental eleven volume work the cultural heritage contained in the myriad estates and grand residences in the once Polish Kresy and Inflanty regions.

- Kresy in Photos of Henryk Poddębski, published in May 2010 in Lublin, with a foreword by people with a Kresy background - Anna Seniuk, Krzesimir Dębski and Maciej Płażyński[43]

- The World of Kresy, with numerous photos, postcards and maps[44]

- Sentimental Journeys. Travel across Kresy with Andrzej Wajda and Daniel Olbrychski[45]

- The Encyclopedia of Kresy, with 3600 articles, and foreword by another famous person from Kresy, Stanisław Lem.[46] Articles about the Eastern Borderlands frequently appear in Polish newspapers and magazines. The local office of Gazeta Wyborcza in Wrocław in late 2010 began a Kresy Family Album, stories and photos of those who were forced to move from the East.

In the first half of 2011, Rzeczpospolita daily published a series called "The Book of Eastern Borderlands" (Księga kresów wschodnich).[47] The July 2012 issue of the Uważam Rze Historia magazine was dedicated to the Eastern Borderlands and their importance in Polish history and culture.[48]

Present day

The territory known to Poles as Kresy is now partitioned off between the states of Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania. Ethnic Poles still live in those areas: in Lithuania, they are the largest ethnic minority in the country (see Poles in Lithuania), in Belarus, they are the second largest ethnic minority in the country after Russians (see Poles in Belarus), and in Ukraine, they officially number 144,130, but some Polish organizations claim that the number of Poles in Ukraine may be as many as 2 million, most of them assimilated.[49] (see Poles in Ukraine). Furthermore, there is a 50,000 Polish minority in Latvia. In Lithuania and Belarus, Poles are more numerous than in Ukraine. This is the result of the Polish population transfers (1944–1946)[50] as well as Massacres of Poles in Volhynia. Those Poles who survived the slaughter begged for the opportunity to emigrate.[19]

Many Polish organizations are active in the former Eastern Borderlands, such as the Association of Poles in Ukraine, Association of Polish Culture of the Lviv Land, the Federation of Polish Organizations in Ukraine, Union of Poles in Belarus, and the Association of Poles in Lithuania. There are Polish sports clubs (Pogoń Lwów, FK Polonia Vilnius), newspapers (Gazeta Lwowska, Kurier Wileński), radio stations (in Lviv and Vilnius), many theatres, schools, choirs and folk ensembles. Poles living in Kresy are helped by a government-sponsored organization Fundacja Pomoc Polakom na Wschodzie, and by other organizations, such as the Association of Help of Poles in the East Kresy (see also Karta Polaka). Money is frequently collected to help those Poles who live in Kresy, and there are several annual events, such as "Christmas Package for a Polish Veteran in Kresy", and "Summer with Poland", sponsored by Association "Polish Community", in which Polish children from Kresy are invited to visit Poland.[51] Polish language handbooks and films, as well as medicines and clothes are collected and sent to Kresy. Books are most often sent to Polish schools which exist there — for example, in December 2010, University of Wrocław organized an event called "Become a Polish Santa Claus and Give a Book to a Polish Child in Kresy".[52] Polish churches and cemeteries (such as Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów) are renovated with money from Poland. For example, in Nysa, money is collected to renovate the Roman Catholic church in Łopatyn near Lviv,[53] while residents of Oława collect funds to renovate the church in Sasiv, also in the area of Lviv.[54] Also, physicians from Kraków's organization Doctors of Hope regularly visit Eastern Borderlands, and the Polish Ministry of Education runs a special program, which sends Polish teachers to the former Soviet Union. In 2007, more than 700 teachers worked in the East, most of them in Kresy.[55] Studio East of Polish TV Wrocław organizes an event called "Save your grandfather's tomb from oblivion" (Mogiłę pradziada ocal od zapomnienia), during which students from Lower Silesia visit Western Ukraine, to clean Polish cemeteries there. In July 2011, about 150 students cleaned 16 cemeteries in the areas of Lviv, Ternopil, Podolia and Pokuttya.[56]

Despite wars and ethnic cleansing many treasures of Polish culture still remain in the East. In Vilnius, there is the Wróblewski Library, with 160,000 volumes and 30,000 manuscripts, which now belong to the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. In Lviv, there is the Ossolineum, one of the most important Polish culture centres. Adolf Juzwenko, current president of Wrocław's office of the Ossolineum, says that in 1945, there was a mass public campaign in Poland, aimed at transporting the whole Ossolineum to Wrocław. It succeeded in recovering only 200,000 volumes, as the Soviets decided that the bulk of the library had to remain in Lviv.[57]

In contemporary Poland

Even though Poland lost its Eastern Borderlands in the aftermath of World War II, Poles connected with the Kresy still have some affection for those lands. Since Poles from current Western Ukraine mostly moved to Silesia. The cities of Wrocław and Gliwice are regarded as miasta lwowskie (cities of Lwów affinity), while Szczecin, Gdańsk and Olsztyn are regarded as miasta wileńskie (cities of Wilno affinity).[58] Lwów's Ossolineum Foundation, its collections and famous library are now located in Wrocław. Polish academics from Lwów established the Polish University of Wrocław (taking over from the old German University of Breslau) and Silesian University of Technology in Gliwice. At the same time, Polish academics from Vilnius founded Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń (even though Toruń belonged to Poland before the outbreak of World War II before 1939).

There are numerous Kresy-oriented organizations, with the largest one, World Congress of Kresy Inhabitants (Światowy Kongres Kresowian), located in Bytom, and branches scattered across Poland, and abroad. The Congress organizes annual World Convention and Pilgrimage of Kresy Inhabitants to Jasna Góra Monastery.[59]

Other important Kresy organizations, active in contemporary Poland, include:

- Polskie Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Krzemieńca i Ziemi Krzemienieckiej (Polish Association of Lovers of Krzemieniec and Krzemieniec Land) from Poznań.

- Stowarzyszenie Kresowe "Podkamień" (Kresy Association "Podkamien") from Wołów,

- Stowarzyszenie Odra-Niemen (Association Odra - Niemen) from Wrocław,

- Stowarzyszenie Przyjaciół Ziemi Drohobyckiej (Association of Friends of Drohobycz Land) from Legnica,

- Stowarzyszenie Rodzin Osadników Wojskowych i Cywilnych Kresów Wschodnich (Association of Families of Osadniks of Eastern Borderlands) from Warsaw,

- Towarzystwo Miłośników Kultury Kresowej (Association of Friends of Kresy Culture) from Wrocław,

- Towarzystwo Miłośników Wołynia i Polesia (Association of Lovers of Wołyn and Polesie) from Warsaw,

- Towarzystwo Miłośników Lwowa i Kresów Południowo-Wschodnich (Association of Lovers of Lwów and Southeastern Kresy) from Wrocław, with branches in Brzeg, Bydgoszcz, Bytom, Chełm, Gdańsk, Jelenia Góra, Kłodzko, Kraków, Leszno, Lublin, Poznań, Szczecinek, Świdwin, Warszawa, Węgliniec and Zabrze,

- Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Grodna i Wilna (Association of Friends of Grodno and Wilno), with branches in Białystok, Ełk, Gdańsk, Giżycko, Lublin, Łódź, Ostrołęka, Stargard Szczeciński, Warszawa, Węgorzewo, Wrocław,

- Związek Sybirakow (Association of Sybiraks) from Warsaw, with branches scattered across Poland and abroad.

Every year, in the Masurian town of Mrągowo, there is a Festiwal Kultury Kresowej (Festival of Kresy Culture), sponsored among others by the Senate of the Republic of Poland and the Minister of Culture, with the patronage of the First Lady. The Festival is broadcast by TVP2 and TVP Polonia, and in 2011 it was organized for the 17th time. Among participants of the 2011 Festival, there were such artists, as Folk Ensemble Mozyrzanka from Mozyr, Children and Youth Band Tęcza from Minsk, Folk Band Kresowianka from Ivyanets, Polish Academic Choir Zgoda from Brest, Instrumental Band Biedronki from Minsk, Vocal Duo Wspólna wędrówka from Minsk, Children's Polonia Ensemble Dolinianka from Stara Huta (Ukraine), Ensemble Fujareczka from Sambir, Ensemble Boryslawiacy from Boryslav, Ensemble Niebo do Wynajecia from Stralhivci (Ukraine), Polish Dance and Song Ensemble Wilenka from Vilnius, Dance and Song Band Troczenie from Trakai, Band Wesołe Wilno from Vilnius, Song and Dance Ensemble Kotwica from Kaunas, and Folk and Polish Folklore Dance and Song Ensemble Syberyjski Krakowiak from Abakan in Siberia.[60]

Other notable Kresy-oriented festivals are:

- Dzień Kresowiaka (Kresy Inhabitant Day) in the village of Lagiewniki near Malbork,

- Dzień Kresowy (Kresy Day) in Wschowa,

- Dzień Kultury Kresowej (Day of Kresy Culture) in Kędzierzyn-Koźle,

- Dni Kultury Kresowej (Days of Kresy Culture) in Białystok,

- Dni Kultury Kresowej (Days of Kresy Culture) in Brzeg,

- Dni Kultury Kresowej (Days of Kresy Culture) in Prochowice,

- Kaziuki (Kaziuko mugė), an annual folk arts and crafts fair, which takes place in Vilnius, is organized in several Polish cities (Gdańsk,[61] Olsztyn,[62] Poznań,[63] Suwałki,[64] Warsaw[65]), on initiative of Poles resettled from Vilnius,

- Kresowy Festiwal Polonijny Młodzieży Szkolnej (Kresy Festival of Polonia Schoolchildren) in Zamość,

- Legnickie Dni Kultury Kresowej (Legnica Days of Kresy Culture) in Legnica, Lubin, Jawor, Chojnów,

- Lipcowy Festiwal Kresowy (July Kresy Festival) in Rejowiec,

- Międzynarodowy Festiwal Kultury Kresowej (International Festival of Kresy Culture) in Jarosław,

- Prezentacja Kultury Polaków z Kresów Wschodnich i Bukowiny (Show of Culture of Poles from Eastern Borderlands and Bucovina) in Zielona Góra, Szprotawa, Nowa Sól, Kożuchów, Żagań

- Świdnicki Dzień Kultury Kresowej i Lwowa (Świdnica Day of Kresy and Lwów Culture) in Świdnica.

In Lubaczów is a Museum of Kresy, and there is a project, supported by local government, to create a Museum of Eastern Borderlands in Wrocław, the city where a number of Poles from Kresy settled after World War II.[66] Numerous photo albums and books, depicting cities, towns and landscapes of Kresy are published every year in Poland. In Chełm, there is Kresy Bicycle Marathon, Polish Radio Białystok every week broadcasts Kresy Magazine, dedicated to the history and present times of the Eastern Borderlands. Every Sunday, Polish Radio Katowice broadcasts a program based on famous prewar Lwów's Merry Wave, every Tuesday, Polish Radio Rzeszów broadcasts a program Kresy Landscapes. In Wrocław, the Association of Remembrance of Victims of Ukrainian Nationalists publishes Na Rubieży (On the Border) magazine. Among best known Kresy activists of contemporary Poland are Father Tadeusz Isakowicz-Zaleski, and Dr. Tadeusz Kukiz, father of popular singer Paweł Kukiz. Since 2007, annual medals Heritage of Eastern Borderlands are awarded in Wrocław. The 2011 recipient was emeritus Archbishop of Wrocław, Henryk Gulbinowicz.[67] Participants of annual Katyń Motorcycle Raid (Motocyklowy Rajd Katyński) always visit Polish centers in Kresy, giving presents to children, and meeting local Poles.[68]

The program of 2011 Days of Kresy Culture (October 22–23) in Brzeg covered such events, as: Kresy themed cabaret, promotion of Kresy books, Eastern Borderlands cuisine, mass in a local church, meetings with Kresy activists and scholars, and theatre shows of Brzeg's Garrison Club as well as Lwów Eaglets Middle School number 3 in Brzeg. Organizers of the festival assured that for the two days Brzeg would turn into the "capital of interwar Polish Kresy".[69]

In January, February and March 2012, Centre for Public Opinion Research did a survey, asking Poles about their ties to Kresy. It turned out that almost 15% of the population of Poland (4,3 - 4,6 million people) declared that they either were born in the Kresy, or have a parent or a grandparent from that region. The number of Kresowiacy is high in northern and western Poland – as many as 51% of inhabitants of Lubusz Voivodeship, and 47% of inhabitants of Lower Silesian Voivodeship stated that their family has ties to the Kresy. Furthermore, Kresowiacy now make 30% of the population of Opole Voivodeship, 25% of the population of West Pomeranian Voivodeship, and 18% of the population of Warmian–Masurian Voivodeship.[70]

Polish regional dialects

Since Poles have lived in Kresy for hundreds of years, two groups of Kresy Polish dialects emerged: the northern (dialekt północnokresowy), and the southern (dialekt południowokresowy).[71] Both dialects have been influenced either by Ukrainian, Belarusian or by Lithuanian. To Polish speakers in Poland, Kresy dialects are easy to distinguish, as their pronunciation and intonation are markedly different from standard Polish.[72] Before World War II, the Kresy provinces were part of Poland, and both dialects were in common usage, spoken by millions of ethnic Poles. After the war and Soviet annexation of Kresy, however, the majority of ethnic Poles were deported westward, resulting in a severe decline in the number of native speakers. The northern Kresy dialect is still used along the Lithuanian-Belarusian border, where Poles still live in large numbers, but the southern Kresy dialect is endangered, as Poles in western Ukraine do not form a majority of the population in any district. Particularly notable among the Kresy dialects is the Lwów dialect which emerged early in the 19th century and was spoken in the city gaining much recognition in the 1920s and 1930s, partly due to the countrywide popularity of numerous Kresy-born and trained actors and comedians whose native speech it was (see also: Dialects of the Polish language).

See also

- Bug River land

- Lithuanian and Belarusian Self-Defence

- Lwów Eaglets

- Peace of Riga

- Poles in the former Soviet Union

- Polish historical regions

- Polish National-Territorial Region

- Polonia

- Republic of Central Lithuania

- Repatriation of Poles (1955–1959)

- Soviet repressions of Polish citizens (1939–1946)

- Suwałki Agreement

- Territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

- Treaty of Warsaw (1920)

- Vilnius Region

- Volhynia Experiment

- Wanda Wasilewska

- West Ukrainian People's Republic

- Zakerzonia

- Żeligowski's Mutiny

References

- ^ "The 2nd edition of the IPN's educational project "Polish Eastern Borderlands in the 20th century"". Institute of National Remembrance. Retrieved 2021-01-24.

- ^ Böhler, Jochen (2018-11-01). Civil War in Central Europe, 1918-1921: The Reconstruction of Poland. Oxford University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-19-251332-8.

- ^ Tomasz Kamusella. 2018. The Russian Okrainy (Oкраины) and the Polish Kresy: Objectivity and Historiography. Global Intellectual History. DOI: 10.1080/23801883.2018.1511186.

- ^ a b Liekis, Šarūnas (2010). 1939: The Year that Changed Everything in Lithuania's History. Rodopi. pp. 257, 361. ISBN 978-90-420-2762-6.

- ^ a b Snyder, Timothy; Brandon, Ray (2014). Stalin and Europe: Imitation and Domination, 1928-1953. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-994558-0.

- ^ Bernd Wegner (1997). From peace to war: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the world, 1939–1941. Berghahn Books. p. 74. ISBN 1-57181-882-0.

- ^ Zbigniew Gołąb, "The Origin and Etymology of Old Russian Kriviči," International Journal of Slavic Linguistics and Poetics 31/32 (1985, Festschrift H. Birnbaum): 167–174, page 173.

- ^ Bremer, T. (2008-04-01). Religion and the Conceptual Boundary in Central and Eastern Europe: Encounters of Faiths. Springer. ISBN 9780230590021.

- ^ "pale, n.1." OED Online. Oxford University Press, September 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016. The Pale was the part of medieval Ireland controlled by the English government.

- ^ Lukowski, Jerzy (2014-06-17). The Partitions of Poland 1772, 1793, 1795. Routledge. ISBN 9781317886938.

- ^ Rafał Żebrowski. "Rocznica wydania ukazu o ustanowieniu "strefy osiedlenia" dla Żydów" (in Polish). Retrieved 2016-01-07. On the anniversary of the institution of the Pale of Settlement

- ^ W dodatku Kresy Wschodnie II Rzeczypospolitej były najbiedniejszym regionem kraju Polska ludność kresowa: rodowód, liczebność, rozmieszczenie Piotr Eberhardt, page 21 Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1998

- ^ Historia gospodarcza Polski Andrzej Jezierski, page 269, 2006

- ^ "Jak odrodziła się wolna Polska". 4 November 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Richter, Klaus (2020-04-02). Fragmentation in East Central Europe: Poland and the Baltics, 1915-1929. Oxford University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-19-258164-8.

- ^ Henschel, Christhardt (2014-11-01). "Front-Line Soldiers into Farmers: Military Colonization in Poland after the First and Second World Wars". Property in East Central Europe: Notions, Institutions, and Practices of Landownership in the Twentieth Century. Berghahn Books. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-78238-462-5.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011-03-01). The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia During World War II. Berghahn Books. p. 61.

- ^ Michael Hope, Polish Deportees in the Soviet Union, Veritas Foundation, London, 2000, ISBN 0-948202-76-9

- ^ a b c Gazeta Wyborcza, Kresowianie nie mieli wyboru, musieli jechać na zachód, interview with Professor Grzegorz Hryciuk, 2010-12-20

- ^ "Gazeta Wrocławska - Wiadomości Wrocław, Informacje Wrocław". 14 August 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Obchody 65. rocznicy przybycia Sybiraków i Kresowiaków na Pomorze Zachodnie". Archived from the original on 21 March 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Wyborcza.pl". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Mieszkańcy Jasienia w Hołdzie Repatriantom z Kresów Wschodnich". Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ czesmen. "Trzcińsko-Zdrój nasza mała ojczyzna - Kresowiacy na Ziemi Chojeńskiej". Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Wykaz repatriantów przybyłych do Wschowy z kresów wschodnich II RP z maja 1945 r." Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ Gazeta Wyborcza, Pierwsza fala przesiedlen

- ^ "Wyborcza.pl". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Nie oddamy Lwowa - Utwory - Cyfrowa Biblioteka Polskiej Piosenki".

- ^ "Gazeta Wyborcza, Kresowe życie na walizkach. Interview with Professor Zdzisław Mach, 2010-12-29". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Polskie Drogi" by Bogdan Trybuchowski

- ^ Historia 1871–1939 Anna Radziwiłł, Wojciech Roszkowski Warsaw 2000 page 278

- ^ "Liczba i rozmieszczenie ludności polskiej na części Kresów obecnie w granicach Ukrainy". Konsnard. 2011.

- ^ a b "Polish census of 1931".

- ^ "Liczebność Polaków na Kresach w obecnej Białorusi". Konsnard. 2011.

- ^ "Liczba i rozmieszczenie ludności polskiej na obszarach obecnej Litwy". Konsnard. 2011.

- ^ "Third Population and Housing Census in Latvia in 1930 (in Latvian and in French)". State Statistical Office.

- ^ Eberhardt, Piotr (1998). "Problematyka narodowościowa Łotwy" (PDF). Zeszyty IGiPZ PAN. 54: 30, Tabela 7 – via Repozytorium Cyfrowe Instytutów Naukowych.

- ^ "Population census 2009". belstat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Bronisław Komorowski na Litwie: Jestem stąd :: społeczeństwo". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ dook.pl. "Bogdan Zdrojewski - Rodzina" (in Polish). Zdrojewski.info. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Ojciec Jolanty Kwaśniewskiej nie żyje - Wiadomości i informacje z kraju - wydarzenia, komentarze - Dziennik.pl". Wiadomosci.dziennik.pl. 13 October 2007. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Gazeta Wrocławska - Wiadomości Wrocław, Informacje Wrocław". 18 September 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Wyborcza.pl". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Dom Spotkań z Historią | "Świat Kresów" – drugie wydanie". Dsh.waw.pl. Archived from the original on 2014-05-24. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Przedszkole pięciolatka pakiet - Kopała Jolanta, Tokarska Elż". Selkar.pl. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Książka Encyklopedia kresów - Ceny i opinie - Ceneo.pl". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ Wydania Archived 2011-06-08 at the Wayback Machine rp.pl

- ^ Uważam Rze Historia (supplement), lipiec 2012 Archived 2017-05-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "2 miliony czy 146 tysięcy?". Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ Ther, Philipp; Siljak, Ana (2001). Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944-1948. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742510944.

- ^ Meksa, Michał (28 July 2011). "Dzieci z Kresów zwiedzają Łódź [ZDJĘCIA]". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Zostań polskim świętym Mikołajem - podaruj książkę polskiemu dziecku na Kresach". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Łopatyn - nyskie serca na kresach". Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ^ Aby nie zapomnieć gdzie są nasze korzenie...

- ^ "700 kresowych nauczycieli". Archived from the original on 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ^ "TVP3 Wrocław - Telewizja Polska S.A." Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Gazeta Wyborcza, Jak przesiedlić kulturę pozostawioną na Kresach, interview with Adolf Juzwenko, 2010-12-23". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Kresowiacy na nowym miejscu, Rzeczpospolita daily". Archived from the original on 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2011-10-19.

- ^ "Światowy Kongres Kresowian". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Festiwal Kultury Kresowej - Informacja Turystyczna w Mrągowie". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Kaziuki w Gdańsku - litewskie święto nad Motławą". Archived from the original on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ^ Wacław. "Olsztyn24 - Kaziuki w Olsztynie". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ profile (1 March 2011). "Wileńskie Kaziuki w Poznaniu". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ Sikorska, Fot. K. (2 March 2009). "Kaziuki w Suwałkach". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ o.o., Avigail Holdings Sp. z. "Kaziuki w Warszawie". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Wyborcza.pl". Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ MGE (8 April 2011). "Wrocław: Medal dla kardynała Gubinowicza". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Komandor Rajdu Katyńskiego: kresy to nasza historia". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "panorama.info.pl". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ CBOS: co siódmy Polak pochodzi z Kresów, onet.pl Retrieved April 16, 2012

- ^ Karaś, Halina. "Gwary polskie - Kresowe odmiany polszczyzny". Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ USA, Translation Services. "Polish Translation. Polish Dialects". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

Bibliography

- Beauvois, Daniel Trójkąt ukraiński, szlachta, carat i lud na Wołyniu, Podolu i Kijowszczyźnie 1793–1914, University of Maria Curie-Sklodowska, Lublin, 2005, 2011 and 2016 (in Polish)

- Mały rocznik statystyczny 1939, Central Statistical Office of Poland, Warsaw 1939 (in Polish)

External links

- Kresy.pl - The Biggest Polish Kresy Portal

- Commonwealth of Diverse Cultures: Poland's Heritage

- Eastern Borderlands of Poland (in English)

- Polish maps of present-day Western Ukraine and Belarus (1930s)

- Virtual Commonwealth - Eastern Borderlands

- Virtual Tour of Kresy Archived 2018-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Volhynia in the Interwar Period

- An extensive digital collection of Kresy-oriented historic publications

- MojeKresy.pl The newest Polish Kresy Portal