Decoy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A decoy (derived from the Dutch de kooi, literally "the cage"[1] or possibly ende kooi, "duck cage"[2]) is usually a person, device, or event which resembles what an individual or a group might be looking for, but it is only meant to lure them. Decoys have been used for centuries most notably in game hunting, but also in wartime and in the committing or resolving of crimes.

Hunting

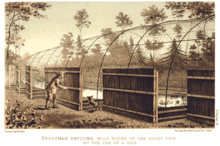

[edit]In hunting wildfowl, the term decoy may refer to two distinct devices. One, the duck decoy (structure), is a long cone-shaped wickerwork tunnel installed on a small pond to catch wild ducks. After the ducks settled on the pond, a small, trained dog would herd the birds into the tunnel. The catch was formerly sent to market for food, but now these are used only by ornithologists to catch ducks to be ringed and released. The word decoy, also originally found in English as "coy", derives from the Dutch de Kooi (the cage) and dates back to the early 17th century, when this type of duck trap was introduced to England from the Netherlands. As "decoy" came more commonly to signify a person or a device than a pond with a cage-trap, the latter acquired the retronym decoy pool.[3]

The other form, a duck decoy (model), otherwise known as a 'decoy duck', 'hunting decoy' or 'wildfowl decoy', is a life-size model of the creature. The hunter places a number about the hunting area as they will encourage wild birds to land nearby, hopefully within the range of the concealed hunter. Originally carved from wood, they are now typically made from plastic.[4]

Wildfowl decoys (primarily ducks, geese, shorebirds, and crows, but including some other species) are considered a form of folk art. Collecting decoys has become a significant hobby both for folk art collectors and hunters. The world record was set in September 2007 when a pintail drake and Canada goose, both by A. Elmer Crowell, sold for 1.13 million dollars apiece.[5][6]

Military decoy

[edit]

The decoy in war is a low-cost device intended to represent a real item of military equipment.

They may be used in different ways:

- deployed in amongst their real counterparts, to divert part of the enemy fire away from the real items of equipment.

- for military deception, fooling the enemy into believing forces in a particular area are much stronger than they really are. One notable example are Quaker Guns.

- to produce a multitude of false signals to overwhelm a radar or sonar defence system, such as flares for IR-guided missiles or chaff for ICBMs.

Bomb decoy

[edit]In irregular warfare, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) are commonly used as roadside bombs to target military patrols. Some guerrillas also use imitation IEDs to intimidate civilians,[7] to waste bomb disposal resources,[8] or to set up an ambush.[9][10][11] Some terrorist groups use fake bombs during a hostage siege, in order to limit hostage rescue efforts.[12][13][14]

Sonar decoy

[edit]A sonar decoy is a device designed to create a misleading reading on sonar, such as the appearance of a false target.

In biochemistry

[edit]In biochemistry, there are decoy receptors, decoy substrates and decoy RNA. In addition, digital decoys are used in protein folding simulations.

Decoy receptor

[edit]Decoy receptors, or sink receptors,[15] are receptors that bind a ligand, inhibiting it from binding to its normal receptor. For instance, the receptor VEGFR-1 can prevent vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) from binding to the VEGFR-2[15] The TNF inhibitor etanercept exerts its anti-inflammatory effect by being a decoy receptor that binds to TNF.[16]

Decoy substrate

[edit]A decoy substrate or pseudosubstrate is a protein that has similar structure to the substrate of an enzyme, in order to make the enzyme bind to the pseudosubstrate rather than to the real substrate, thus blocking the activity of the enzyme. These proteins are therefore enzyme inhibitors.

Examples include K3L produced by vaccinia virus, which prevents the immune system from phosphorylating the substrate eIF-2 by having a similar structure to eIF-2. Thus, the vaccinia virus avoids the immune system.

Digital decoys

[edit]In protein folding simulations, a decoy is a computer-generated protein structure which is designed so to compete with the real structure of the protein. Decoys are used to test the validity of a protein model; the model is considered correct only if it is able to identify the native state configuration of the protein among the decoys.

Decoys are generally used to overcome a main problem in protein folding simulations: the size of the conformational space. For very detailed protein models, it can be practically impossible to explore all the possible configurations to find the native state. To deal with this problem, one can make use of decoys. The idea behind this is that it is unnecessary to search blindly through all possible conformations for the native conformation; the search can be limited to a relevant sub-set of structures. To start with, all non-compact configurations can be excluded. A typical decoy set will include globular conformations of various shapes, some having no secondary structures, some having helices and sheets in different proportions. The computer model being tested will be used to calculate the free energy of the protein in the decoy configurations. The minimum requirement for the model to be correct is that it identifies the native state as the minimum free energy state (see Anfinsen's dogma).

See also

[edit]- Boarstall Duck Decoy – Waterfowl trap in England

- Decoy effect – Phenomenon in marketing

- Game call – device that is used to mimic animal communication noises to attract or drive animals to a hunter

- Hale Duck Decoy – Waterfowl trap and nature reserve in England

- Honeypots – Computer security mechanism

- Maskirovka – Russian military doctrine

- Mobile submarine simulator – American sonar decoy

- Penetration aid – Intercontinental ballistic missile device

- Red herring – Fallacious approach to mislead an audience

- Sting operation – Deceptive way to catch a person committing a crime

- XGAM-71 Buck Duck – American decoy missile prototype

- Garden owl - Pest control decoy

References

[edit]- ^ Cresswell, Julia (2021). Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192639370.

- ^ Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 71.

- ^ Janet (1993). "Duck decoys, with particular reference to the history of bird ringing". Archives of Natural History. 20 (2): 229–240. doi:10.3366/anh.1993.20.2.229. ISSN 0260-9541.

- ^ Mackey, William J. (1987). American bird decoys. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-24500-1.

- ^ Frangoulis, George (2014). Ducks and Decoys. tuscaloosa, Alabama: The Farmstead Press. ISBN 978-1-312-60897-9.

- ^ "To tune of $1.13m, decoys are the real thing". The Boston Globe. 2007-09-21. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ "Four decoy IEDs found in Port Said polling stations - Egypt Independent". 25 May 2014.

- ^ Article title Archived 2022-09-30 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "In Battle, Hunches Prove to Be Valuable". The New York Times. 28 July 2009.

- ^ ""One enemy TTP is to set decoy IEDs in order to observe the immediate reactions of coalition forces. By studying our tactics they can increase the lethality of their attacks, like setting up mortars and rockets on the kill zone or safe area." (PDF)" (PDF). Retrieved Apr 12, 2019.

- ^ James H. Lebovic (2010). The Limits of U.S. Military Capability: Lessons from Vietnam and Iraq. JHU Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8018-9750-4.

- ^ Bonnie Malkin in Sydney (6 September 2011). "Video: Man takes female hostage in Sydney office bomb siege - Telegraph". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011.

- ^ "We're for Sydney". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2019-04-12.

- ^ "How Sydney siege gunman tricked police into thinking there was a bomb in his backpack". The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 December 2014.

- ^ a b Hugo H. Marti (2013). Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Landes Bioscience.

- ^ Zalevsky J, Secher T, Ezhevsky SA, et al. (August 2007). "Dominant-negative inhibitors of soluble TNF attenuate experimental arthritis without suppressing innate immunity to infection". J. Immunol. 179 (3): 1872–83. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1872. PMID 17641054.

External links

[edit]- Decoy Magazine, Joe Engers - The ultimate publication for decoy lovers and collectors

- The Midwest Decoy Collectors Association – The de facto international collectors association

- The Book of Duck Decoys – Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey, 1886 (full text)

- British Duck Decoys of To-Day, 1918 – Joseph Whitaker (full text)