German occupation of Estonia during World War II

After Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941,the Wehrmacht reached Estonia in (July 1941). Although initially the Germans were perceived as liberators from the USSR and its repressions by most Estonians in hope for restoration of the countries independence, it was soon realized that they were but another occupying power. Germans pillaged the country for the war effort and unleashed the Holocaust. Estonia was incorporated into the German province of Ostland.

German Occupation in Estonia 1941-1944

After Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, On June 25, Finland sided with Germany in the Continuation War. On July 3, Stalin made his public statement over the radio calling for Scorched earth policy in the areas to be abandoned. In Estonia, the assault of the Soviet destruction battalions was the worst, because the northernmost areas were the last to be "liberated," allowing the Soviet occupiers more time to linger. The Estonian forest brothers, numbering about 50.000 inflicted heavy casualties on the remaining Soviets as many as 4800 were killed and 14000 captured.

Germans crossed the Estonian southern border on July 7-9. The Russian 8th Army (Major General Ljubovtsev), retreated in front of the 2nd corps of the German Army behind the Pärnu River- the Emajõgi line on July 12. As German 'troops' approached Tartu on July 10 and prepared for another battle with the Soviets, they realized that the Estonian partisans were already in fight with the Soviet troops. Wehrmacht stopped its advance and hung back, leaving the Estonians to do the fighting. The battle of Tartu lasted 'two 'weeks, and destroyed most of the city. Under the leadership of Friedrich Kurg the Estonian partisans drove out the Soviets from Tartu on their own. While Soviets had been in the process of murdering citizens held in Tartu Prison and had killed 192 before the Estonians captured the city.

At the end July the Germans resumed their advance in Estonia working in tandem with the Estonian Forest Brothers. Both German troops and Estonian partisans took Narva on August 17 and the Estonian capital Tallinn on August 28. On that day, the red flag ![]() shot down earlier on Pikk Hermann was replaced with the Flag of Estonia

shot down earlier on Pikk Hermann was replaced with the Flag of Estonia ![]() by Fred Ise. After the Soviets were driven out from Estonia German troops disarmed all the partisan groups. [1] The Estonian flag

by Fred Ise. After the Soviets were driven out from Estonia German troops disarmed all the partisan groups. [1] The Estonian flag ![]() is replaced shortly with the flag of Germany.

is replaced shortly with the flag of Germany. ![]()

Most Estonians greeted the Germans with relatively open arms and hoped for restoration of independence. Estonia set up a government administrations, led by Jüri Uluots as soon as the Soviet regime retreated and before German troops arrived. Estonian partisans that drove the Red Army from Tartu made it possible. That all was for nothing since the Germans disbanded the provisional government and Estonia became a part of the German-occupied "Ostland". A Sicherheitspolizei was established for internal security under the leadership of Ain-Ervin Mere.

In April 1941, on the eve on the German invasion, Alfred Rosenberg, Reich minister for the Occupied Eastern territories, a Baltic German, born and raised in Tallinn, Estonia, laid out his plans for the East. According to Rosenberg a future policy was created:

- Germanization (Eindeutschung) of the "racially suitable" elements.

- Colonization by Germanic peoples.

- Exile, deportations of undesirable elements.

Rosenberg felt that the "Estonians were the most Germanic out of the people living in the Baltic area, having already reached 50 percent of Germanization through Danish, Swedish and German influence". Non-suitable Estonians were to be moved to a region that Rosenberg called "Peipusland" to make room for German colonists. [2]

The initial enthusiasm that accompanied the liberation from Soviet occupation quickly waned as a result and the Germans had limited success in recruiting volunteers. The draft was introduced in 1942, resulting in some 3400 men fleeing to Finland to fight in the Finnish Army rather than join the Germans. Finnish Infantry Regiment 200 AKA (Estonian: soomepoisid) was formed out of Estonian volunteers in Finland.

With the Allied victory over Germany becoming certain in 1944, the only option to save Estonia's independence was to stave off a new Soviet invasion of Estonia until Germany's capitulation.

Estonian National "Underground Government"

In June 1942 political leaders of Estonia who had survived Soviet repressions hold a hidden meeting from the occupying powers in Estonia where the formation of an underground Estonian government and the options for preserving continuity of the republic were discussed.[3]

On January 6 1943 a meeting hold at the Estonian foreign delegation in Stockholm. In order to preserve the legal continuation of the Republic of Estonia, the last constitutional prime minister, Jüri Uluots, must continue to fulfill his responsibilities as prime minister was decided.[3][4]

On June 1944 – the elector’s assembly of the Republic of Estonia gathers in secrecy from the occupying powers in Tallinn and appoints Jüri Uluots as the prime minister with responsibilities of the President. On June 21 – Jüri Uluots appoints Otto Tief as deputy prime minister. [3]

As the Germans retreated in September 1944, on September 18 Jüri Uluots formed a government led by the

Deputy Prime Minister, Otto Tief. On September 20 The flag ![]() on Pikk Hermann was replaced with

on Pikk Hermann was replaced with ![]() the flag of Estonia. On September 22 the Red Army took Tallinn and the flag

the flag of Estonia. On September 22 the Red Army took Tallinn and the flag ![]() on Pikk Hermann was replaced with

on Pikk Hermann was replaced with ![]() . The Estonian underground government, not officially recognized by either the Nazi Germany or Soviet Union, fled to Stockholm, Sweden and operated in exile until 1992, when Heinrich Mark, the Prime Minister of the Republic of Estonia in duties of the President in exile [5], presented his credentials to the newly elected President of Estonia Lennart Meri. On February 23. 1989 The flag of Estonian SSR

. The Estonian underground government, not officially recognized by either the Nazi Germany or Soviet Union, fled to Stockholm, Sweden and operated in exile until 1992, when Heinrich Mark, the Prime Minister of the Republic of Estonia in duties of the President in exile [5], presented his credentials to the newly elected President of Estonia Lennart Meri. On February 23. 1989 The flag of Estonian SSR ![]() had been lowered on Pikk Hermann, it had been replaced with the flag of Estonia

had been lowered on Pikk Hermann, it had been replaced with the flag of Estonia ![]() on February 24, 1989.

on February 24, 1989.

Estonian Military Units in 1941-1944

Up to March 1942 drafted Estonians mostly served in the rear of the Army Group North security. On August 28, 1942 the German powers announced the legal compilation of the Estonian Legion within the Waffen SS. Oberführer Frans Augsberger was nominated the commander of the legion. Up to the end of 1942 about 1280 men volunteered into the training camp. Bataillon Narwa was formed from the first 800 men of the Legion to have finished their training at Heidelager, being sent in April 1943 to join the Division Wiking in Ukraine. They replaced the Finnish Volunteer Battalion, recalled to Finland for political reasons. [6] In March 1943 the partial mobilisation was carried out in Estonia during which 12,000 men were called into service. On May 5, 1943 the 3rd Estonian Waffen-SS brigade was formed and sent to front near Nevel.

By January 1944, the front was pushed back by the Red Army almost all the way to the former Estonian border. Jüri Uluots, the last constitutional prime minister of the republic of Estonia [7], the leader of Estonian underground government delivered a radio address on February 7 [3]that implored all able-bodied men born from 1904 through 1923 to report for military service (Before this, Uluots had opposed Estonian mobilization.) The call drew support from all across the country: 38.000 volunteers jammed registration centers. [8] Several thousand Estonians who had joined the Finnish army came back across the Gulf of Finland to join the newly formed Territorial Defense Force, assigned to defend Estonia against the Soviet advance. In autumn 1944 there was the same amount of Estonians as at the time of the Estonian War of Independence, in total about 100,000 men. The initial formation of the volunteer Estonian Legion created in 1942 was eventually expanded to become a full-sized conscript division of the Waffen SS in 1944, the 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian). The Estonian units saw action defending the Narva line throughout 1944. It was hoped that by engaging in such a war Estonia would be able to attract Western support for the cause of Estonia's independence from the USSR and thus ultimately succeed in achieving independence. [9]

On February 1, 1944 the Red Army reached the border of Estonia as a part of the great offensive which began on January 14. Field Marshal Walter Model was nominated the leader of the German Army Group North. The Soviet attack led by Soviet General Leonid A. Govorov, the commander of the Leningrad Front, began on February 13. On February 24 ( Estonian National Day) the counterattack of the Estonian division to break the Soviet bridgeheads began. The Estonian battalion led by Rudolf Bruus destroyed the Soviet bridgehead. The Estonian battalion led by Ain - Ervin Meri liquidated another bridgehead of Vaasa-Siivertsi-Vepsaküla. On March 6, the task was fulfilled. The leadership of the Red Army draw 9 corps under Narva against 7 divisions and one brigade. On March 1, a new Soviet offensive began in the direction of Auvere. The assault was stopped by the 658th battalion led by Alfons Rebane. On March 17, Soviets attacked with the forces of 20 divisions against 3 defensive, but could not break the defense. On April 7, the leadership of the Red Army ordered to go over to defense. In March the Soviets organised many bombing attacks towards the towns of Estonia incl. bombing of Tallinn on March 9.

On July 24 the Soviets began a new attack in the direction of Auvere . They were stopped by I battalion (Stubaf Paul Maitla) of the 45 regiment (Riipalu) and the fusiliers (previous "Narva") under the leadership of Hatuf Hando Ruus. Finally The evacuation of Narva was organised and front was settled on the line of "Tannenberg" in Sinimäed.

On August 1 the Finnish government and President Ryti were to resign. On the next day, Aleksander Warma the Estonia's Ambassador to Finland (1939-1940(1944)) [10] fannounced that the National Committee of the Estonian Republic had sent a telegram, which stated "Estonians return home!" On the following day, the Finnish government received a letter from the Estonians. It had been signed in the name of "all national organizations of Estonia" by Aleksander Warma, Karl Talpak and several others. In the letter, the Finnish government was asked to send the Estonian volunteer regiment back to Estonia fully equipped. It was then announced that JR 200 would be disbanded and that the volunteers were free to return home. An agreement had been reached with the Germans, and the Estonians were promised amnesty if they were to return. As soon as they landed, the regiment was sent to perform a counter-attack against the Soviet 3rd Baltic Front, which had managed a break-through on the Tartu front, and was threatening the capital Tallinn.

When the break-through in Tannenberg Line/Sinimäed failed, the main struggle was carried to the south of the Lake Peipus, where on August 11, Petseri was taken and Võru on August13. Near Tartu the Red Army was stopped by the military groups sent from Narva under the command of Alfons Rebane and Paul Vent and 5th SS Volunteer Sturmbrigade Wallonien led by Léon Degrelle.

On August 19, 1944 Jüri Uluots calls in a radio broadcast for holding back the Red Army until a peace treaty is reached.[3]

As Finland left the war on September 4, 1944 according to the peace agreement with Soviets the defence of the mainland became impossible and the command of the German Army decided to evacuate from Estonia. Estonian islands showed resistance until November 23, 1944, when Sõrve was evacuated. According to the Soviet data, the conquering of the territory of Estonia cost them 126,000 casualties, in the German data the number is 170,000. On the German side, their own data shows 30,000 dead which is most likely underrated, the more realistic figure would be 45,000. [11]

Other volunteers that paricipated in the Battle of Narva and the Battle of the Tannenberg Line within the Waffen SS were from Norway, Denmark, Holland and Belgium.

Administrators of German occupied Estonia 1941 - 1944

German administrators

In 1941 Estonia was occupied by German troops and after a brief period of military rule - dependent of the Commanders of the Army Group North (in the occupied U.S.S.R.) - a German civilian administration was established and Estonia was organized as a General Kommissariat becoming soon afterwards part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland.

Generalkommissar

(subordinated to the Reichskommissar Ostland)

- 1941 - 1944 SA-Obergruppenfuhrer Karl Sigismund Litzmann (1893)

S.S. und Polizeiführer

(responsible for internal security and war against the resistance - directly subordinated to the H.S.S.P.F. of Ostland, not to the Generalkommissar)

- 1941 - 1944 SS-Oberführer Hinrich Möller (1906 - 1974)

- 1944 SS-Brigadeführer Walter Schröder (1902 - 1973)

Lagerkommandant

(responsible for the operation of all concentration camps within the Reichskommissariat Ostland)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Hans Aumeier (1906 - 1947)

Estonian administrators

It has been suggested that Estonian Self-Administration be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since June 2007. |

An indigenous Estonian administration was established immediately after the conquest by the German occupation forces. It was formally recognized by the German central authorities in 1942. According to Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity

- Although the Directorate did not have complete freedom of action, it exercised a significant measure of autonomy, within the framework of German policy, political, racial and economic. For example, the Directors exercised their powers pursuant to the laws and regulations of the Republic of Estonia, but only to the extent that these had not been repealed or amended by the German military command.[12]

Landesdirektoren

Landsdirector - General

- 1941 - 1944 Hjalmar Mäe (1901 - 1978)

Landsdirector for Home Affairs

- 1941 - 1944 Oskar Angelus (1892 - 1979)

Landsdirectors for Justice

- 1941 - 1943 Hjalmar Mäe

- 1943 - 1944 Oskar Öpik

Landsdirector for Finance

- 1941 - 1944 Alfred Wendt (1902)

Holocaust in Estonia 1941 - 1944

Historical background

The process of Jewish settlement in Estonia began in the nineteenth century, when in 1865 Alexander II of Russia granted them the right to enter the region. The creation of the Republic of Estonia in 1918 marked the beginning of a new era for the Jews. Approximately 200 Jews fought in combat for the creation of the Republic of Estonia and 70 of these men were volunteers. From the very first days of her existence as a state, Estonia showed her tolerance towards all the peoples inhabiting her territories. On 12 February 1925 The Estonian government passed a law pertaining to the cultural autonomy of minority peoples. The Jewish community quickly prepared its application for cultural autonomy. Statistics on Jewish citizens were compiled. They totaled 3,045, fulfilling the minimum requirement of 3000 for cultural autonomy. In June 1926 the Jewish Cultural Council was elected and Jewish cultural autonomy was declared. Jewish cultural autonomy was of great interest to global Jewish community. The Jewish National Endowment presented the Estonian government with a certificate of gratitude for this achievement. [13]

There were, at the time of Soviet occupation in 1940, approximately 4000 Estonian Jews. The Jewish Cultural Autonomy was immediately abolished. Jewish cultural institutions were closed down. Many of Jewish people were deported to Siberia along with other Estonians by the Soviets. It is estimated that 350-500 Jews suffered this fate.[14][15][16] About three-fourths of Estonian Jewry managed to leave the country during this period.[17][18] Out the approximately 4,300 Jews in Estonia prior to the war, almost 1000 were entrapped by the Nazis.[19][20]

With the invasion of the Baltics, it was the intention of the Nazi government to use the Baltics countries as their main area of mass genocide. Consequently, Jews from countries outside the Baltics were shipped there to be exterminated. Round-ups and killings of Jews began immediately following the arrival of the first German troops in 1941, who were closely followed by the extermination squad Einsatzkommando (Sonderkommando) 1A under Martin Sandberger, part of Einsatzgruppe A led by Walter Stahlecker. Arrests and executions continued as the Germans, with the assistance of local collaborators, advanced through Estonia.

Unlike German forces, Estonians seem to have supported the anti-Jewish actions on the political level, but not on a racial basis. The standard form used for the cleansing operations was arrest 'because of communist activity'. The equation between Jews and communists evoked a positive Estonian response, and attempts were made by Estonian police to determine whether the arrested person indeed supported communism. Estonians often argued that their Jewish colleagues and friends were not communists and submitted proofs of pro-Estonian conduct in hope to get them released.[19]

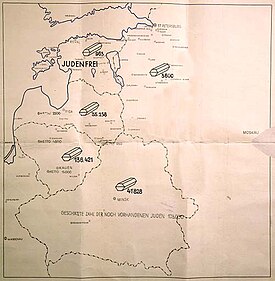

Estonia was declared Judenfrei quite early, at the Wannsee Conference. [21] Jews that had remained in Estonia (921 according to Martin Sandberger, 929 according to Evgenia Goorin-Loov and 963 according to Walter Stahlecker) were killed. [3] Fewer than a dozen Estonian Jews are known to have survived the war in Estonia. The Nazi regime also established 22 concentration and labor camps in Estonia for foreign Jews. The largest, Vaivara concentration camp housed 1,300 prisoners at a time. These prisoners were mainly Jews, with smaller groups of Russians, Dutch, and Estonians.[22] Several thousand foreign Jews were killed at the Kalevi-Liiva camp. [23] Four Estonians most resposible for the murders at Kalevi-Liiva were accused at war crimes trials in 1961. Two were later executed, two other avoided sentencing in exile. There have been knowingly 7 ethnic Estonians: Ralf Gerrets, Ain-Ervin Mere, Jaan Viik, Juhan Jüriste, Karl Linnas, Aleksander Laak and Ervin Viks that have faced trials for crimes against humanity. Since the reestablishment of the Estonian independence markers were put in place for the 60th anniversary of the mass executions that were carried out at the Lagedi, Vaivara and Klooga (Kalevi-Liiva) camps in September of 1944. [24]

Estonian military units' involvement in crimes against humanity

The Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity [25] has reviewed the role of Estonian military units and police battalions in an effort to identify the role of Estonian military units and police battalions participation during the World War II in crimes against humanity.

The conclusions of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity are available online.[25] It says that there is an evidence of Estonian units' involvement in crimes against humanity, and acts of genocide; however, commission noted

- Given the frequency with which police units changed their personnel, the Commission does not believe that membership in the cited units, or in any specific unit is, on its own, proof of involvement in crimes. However, those individuals who served in the units during the commission of crimes against humanity are to be held responsible for their own actions.

Controversies

Views diverge on history of Estonia during the WWII and following the occupation by Nazi Germany.

- The position of the Estonian Government: Occupation of Estonia by Nazi Germany ended with five decades of Soviet occupation of the Baltic nations. [26] The European parliament has issued a resolution on the issue supporting the positions of The Estonian Government: as an independent Member State of the EU and NATO, has the sovereign right to assess its recent tragic past, starting with the loss of independence as a result of the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939 and including three years under Hitler’s occupation and terror, as well as 48 years under Soviet occupation and terror whereas the Soviet occupation and annexation of the Baltic States was never recognized as legal by the Western democracies, [27]

- The position of the Russian Government: Russia has denied it illegally annexed the Baltic republics of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia in 1940. The Kremlin's European affairs chief Sergei Yastrzhembsky: "There was no occupation." [28] Russian State officials look at the events in Estonia in the end of the WWII as the liberation from fascism by the Soviet Union . [29]

- Views of WWII veteran, an Estonian Ilmar Haaviste fought on the German side: “Both regimes were equally evil - there was no difference between the two except that Stalin was more cunning”.

- Views of WWII veteran, an Estonian Arnold Meri fought on the Soviet side: "Estonia's participation in World War II was inevitable. Every Estonian had only one decision to make: whose side to take in that bloody fight - the Nazis' or the anti-Hitler coalition's."

- Views of WWII veteran, a Russian fought on the Soviet side in Estonia answering a question: How do you feel being called an "occupier"? " Viktor Andreyev: "Half believe one thing half believe another. That's in the run of things." [30]

In 2004 controversy regarding the events of WWII in Estonia surrounded the Monument of Lihula.

In April 2007 the diverge views on history of WWII in Estonia centered around the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn.

See also

- 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian)

- Estonian resistance movement

- Judenfrei

- Klooga concentration camp

- Reichskommissariat Ostland

References

- ^ Resistance! Occupied Europe and Its Defiance of Hitler by Dave Lande on Page 188, ISBN 0760307458

- ^ Estonia and the Estonians (Studies of Nationalities) Toivo U. Raun ISBN 0817928529

- ^ a b c d e Chronology at the EIHC

- ^ Mälksoo, Lauri (2000). Professor Uluots, the Estonian Government in Exile and the Continuity of the Republic of Estonia in International Law. Nordic Journal of International Law 69.3, 289-316.

- ^ Heinrich Mark at president.ee

- ^ ESTONIAN VIKINGS: Estnisches SS-Freiwilligen Bataillon Narwa and Subsequent Units, Eastern Front, 1943-1944

- ^ Jüri Uluots at president.ee

- ^ Resistance! Occupied Europe and Its Defiance of Hitler by Dave Lande on Page 200 ISBN 0760307458

- ^ The Baltic States: The National Self-Determination of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania Graham Smith p.91 ISBN 0312161921

- ^ http://www.president.ee/en/estonia/heads.php?gid=81977 Aleksander Warma] at president.ee

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

HWwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Conclusions of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity - Phase II: The German occupation of Estonia in 1941–1944

- ^ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Estonia.html?title=Jews_in_Estonia&action=edit

- ^ Weiss-Wendt, Anton (1998). The Soviet Occupation of Estonia in 1940-41 and the Jews. Holocaust and Genocide Studies 12.2, 308-325.

- ^ Berg, Eiki (1994). The Peculiarities of Jewish Settlement in Estonia. GeoJournal 33.4, 465-470.

- ^ http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/holocaust.html

- ^ Conclusions of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity - Phase II: The German occupation of Estonia in 1941–1944

- ^ http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005448

- ^ a b Birn, Ruth Bettina (2001), Collaboration with Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe: the Case of the Estonian Security Police. Contemporary European History 10.2, 181-198. Cite error: The named reference "birn" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/holocaust.html

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/Vaivara.html

- ^ [2]

- ^ http://www.heritageabroad.gov/projects/estonia1.html

- ^ a b Conclusions of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity

- ^ http://newsfromrussia.com/cis/2005/05/03/59549.html

- ^ http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+MOTION+B6-2007-0215+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4517683.stm

- ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article1714401.ece

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6637895.stm

External links

- Birn, Ruth Bettina (2001), Collaboration with Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe: the Case of the Estonian Security Police. Contemporary European History 10.2, 181-198.

- Estonian volunteers to the Waffen SS

- Estonian SS-Legion (photographs)

- Estonian SS-Legion (photographs)

- Estonian SS volunteers, Russia 1944

- Hjalmar Mäe

- Hjalmar Mäe (photograph)

- Saksa okupatsioon Eestis

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2003). Extermination of the Gypsies in Estonia during World War II: Popular Images and Official Policies. Holocaust and Genocide Studies 17.1, 31-61.