Ceratosaurus

| Ceratosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

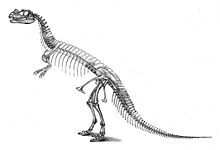

| Mounted juvenile skeleton, Wisconsin | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Infraorder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Ceratosaurus Marsh, 1884

|

| Species | |

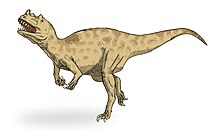

Ceratosaurus (Template:Pron-en) meaning "horned lizard", in reference to the horn on its nose (Greek κερας/κερατος, keras/keratos meaning "horn" and σαυρος/sauros meaning "lizard"), was a large predatory dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Period (Kimmeridgian to Tithonian), found in the Morrison Formation of North America, in Tanzania and Portugal. It was characterized by large jaws with blade-like teeth, a large, blade-like horn on the snout and a pair of hornlets over the eyes. The forelimbs were powerfully built but very short. The bones of the sacrum were fused (synsacrum) and the pelvic bones were fused together and to this structure (Sereno 1997) (i.e. similar to modern birds). A row of small osteoderms was present down the middle of the back.

Description

Ceratosaurus was a fairly typical theropod, with a large head, short forelimbs, robust hind legs, and a long tail.[1][2]

Skull

The skull of Ceratosaurus was quite large in proportion to the rest of its body.[3] Each premaxilla contained only three teeth, and each maxilla (the main tooth-bearing bones in the upper jaw) held between twelve and fifteen flattened, exceptionally long teeth. Each dentary (the main tooth-bearing bone in the lower jaw) bore eleven to fifteen teeth.[4][5] The prominent nose horn is formed from protuberances of the nasal bones.[6] A juvenile specimen is known in which the two halves of the horn are not yet fused together.[7] In addition to the large nasal horn, Ceratosaurus possessed smaller hornlike ridges in front of each eye, similar to those of Allosaurus. These ridges were formed by enlargement of the lacrimal bones.[8]

Postcranial skeleton

Uniquely among theropods, Ceratosaurus possessed dermal armor, in the form of small osteoderms running down the middle of its back.[4] The tail of Ceratosaurus comprised about half of the body's total length.[4] It was thin and flexible, with high vertebral spines.[3]

Size

The type specimen was an individual about 17.5 feet (5.3 m) long; it is not clear whether this animal was fully grown.[4][9] David B. Norman (1985) estimated that the maximum length of Ceratosaurus was 20 feet (6 m).[2] A particularly large Ceratosaurus specimen from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry (UUVP 81), discovered in the mid-1960s, may have been up to 30 feet (8.8 m) long.[10]

Marsh (1884) suggested that Ceratosaurus weighed about half as much as Allosaurus.[3] In Predatory Dinosaurs of the World, published in 1988, Gregory S. Paul estimated that the C. nasicornis holotype skeleton came from an animal weighing about 524 kilograms (1,155 lb). A large femur from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry represents a much bigger and heavier individual, whose bulk was estimated by Paul at about 980 kilograms (2,160 lb).[11] This specimen (UUVP 56) was later assigned by James H. Madsen and Samuel P. Welles to the new species C. dentisulcatus.[5] A considerably lower figure was proposed by John Foster, a specialist on the Morrison Formation, in 2007. Foster used an equation provided by J.F. Anderson and colleagues to estimate mass from femur length, which yielded an approximate weight of 275 kilograms (606 lb) for C. magnicornis and 452 kilograms (996 lb) for C. dentisulcatus.[8]

Discovery and species

Ceratosaurus is known from the Cleveland Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in central Utah and the Dry Mesa Quarry in Colorado. The type species, described by O. C. Marsh in 1884 and redescribed by Gilmore in 1920, is Ceratosaurus nasicornis. Two further species were described in 2000: C. magnicornis (from the Fruita Paleontontological Area, outside Fruita, Colorado) and C. dentisulcatus.[12] C. magnicornis has a slightly rounder horn but is otherwise highly similar to C. nasicornis; C. dentisulatus is larger (over 7 meters), slightly more derived, and has an unknown horn shape (assuming it had them). The Portuguese remains have recently been ascribed to C. dentisulcatus (Mateus et al. 2006). More additional species, including C. ingens and C. stechowi, have been described from less complete material. Present in stratigraphic zones 2 and 4-6 of the Morrison Formation.[13]

Ceratosaurus species:

- C. nasicornis (type)

- C. dentisulcatus

- C. magnicornis

- C. ingens

- C. stechowi

- C. meriani

Paleobiology

Ceratosaurus lived alongside dinosaurs such as Allosaurus, Torvosaurus, Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, and Stegosaurus. Ceratosaurus reached lengths of 6 to 8 meters (20 to 27 feet), was around 2.5 meters (8 feet) tall, and weighed between 500 kg and 1 tonne. It was smaller than the other large carnivores of its time (allosaurs and Torvosaurus) and likely occupied a distinctly separate niche from them. Ceratosaurus fossils are noticeably less common than those of Allosaurus, but whether this implies Ceratosaurus being rarer is uncertain (animals with certain lifestyles are more biased toward fossilization than others). Ceratosaurus had a longer, more flexible body, with a deep tail shaped like that of a crocodilian.[4] This suggests that it was a better swimmer than the stiffer Allosaurus. A recent study by Bakker suggested that Ceratosaurus generally hunted aquatic prey, such as fish and crocodiles, although it had potential for feeding on large dinosaurs. The study also suggests that sometimes adults and juveniles ate together.[14] This evidence is debatable, and Ceratosaurus tooth marks are very common on large, terrestrial dinosaur prey fossils. Scavenging from corpses, smaller predators, and after larger ones also likely accounted for some of its diet.

Nasal horn

Marsh (1884) considered the nasal horn of Ceratosaurus to be a "most powerful weapon" for both offensive and defensive purposes, and Gilmore (1920) concurred with this analysis.[3][4] However, this interpretation is now generally considered unlikely.[10] Norman (1985) believed that the horn was "probably not for protection against other predators," but might instead have been used for intraspecific combat among male ceratosaurs contending for breeding rights.[2] Paul (1988) suggested a similar function, and illustrated two Ceratosaurus engaged in a non-lethal butting contest.[11] Rowe and Gauthier (1990) went further, suggesting that the nasal horn of Ceratosaurus was "probably used for display purposes alone" and played no role in physical confrontations.[6] If used for display, it is likely that the horn would have been brightly colored.[8]

Classification

Relatives of Ceratosaurus include Genyodectes, Elaphrosaurus, and the abelisaurs, such as Carnotaurus. The classification of Ceratosaurus and its immediate relatives has been under intense debate recently. Ceratosaurus is unique in its characters; it is too advanced and basal tetanuran-like to be a large, late coelophysoid and too primitive in many manners to be a true carnosaur. Its closest relatives appear to be the abelisaurs from the Cretaceous, but again, Ceratosaurus is an enigma in its existing tens of millions of years before them with no obvious Early Cretaceous link between them.

In the past, Ceratosaurus, the Cretaceous abelisaurs, and the primitive coelophysoids were all grouped together and called Ceratosauria, defined as "theropods closer to Ceratosaurus than to Aves". Recent evidence, however, has shown large distinctions between the later, larger and more advanced ceratosaurs and earlier forms like Coelophysis. While considered distant from birds among the theropods, Ceratosaurus and its kin were still very bird-like, and even had a more avian tarsus (ankle joint) than Allosaurus. As with all dinosaurs, the more fossils found of these animals, the better their evolution and relationships can be understood.

In popular culture

Ceratosaurus has appeared in several films, including the first live action film to feature dinosaurs, D. W. Griffith's Brute Force (1914).[15] In the Rite of Spring segment of Fantasia (1940), Ceratosaurus are shown as opportunistic predators attacking Stegosaurus and Diplodocus trapped in mud. In The Animal World (1956) a Ceratosaurus kills a Stegosaurus in battle, but is soon attacked by another Ceratosaurus trying to steal a meal. This scene ends with both Ceratosaurus falling to their deaths off the edge of a very high cliff.

A Ceratosaurus battles a Triceratops in the 1966 remake of One Million Years B.C.. Ceratosaurus is also featured in The Land That Time Forgot (1975) where it battles a Triceratops, and its sequel The People That Time Forgot (1977) in which Patrick Wayne's character rescues a cavegirl from two pursuing Ceratosaurus by driving the dinosaurs off with smoke bombs (after having failed to frighten them off by firing shots in the air once the Ceratosaurus' attention had been shifted to Patrick Wayne's party of explorers). More recently, a Ceratosaurus makes a brief appearance in the film Jurassic Park III in which it is repelled from attacking the main characters by a large mound of Spinosaurus dung. This dinosaur also appears in the television documentary When Dinosaurs Roamed America, a Ceratosaurus makes a few appearances as a predator, killing Dryosaurus and eating it, but is later killed and eaten by an Allosaurus. Ceratosaurus is also featured in episodes of Jurassic Fight Club where it is seen as a rival to Allosaurus and preying on Stegosaurus.

References

- Mateus, O., Walen, A. & Antunes, M.T. (2006). The large theropod fauna of the Lourinhã Formation (Portugal) and its similarity to the Morrison Formation, with a description of a new species of Allosaurus. in Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S. G. R.M., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36

Footnotes

- ^ Marsh, O.C. (1892). "Restorations of Claosaurus and Ceratosaurus". American Journal of Science. 44 (262): 343–349.

- ^ a b c Norman, D.B. (1985). "Carnosaurs". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Salamander Books Ltd. pp. 62–67. ISBN 0517468905.

- ^ a b c d Marsh, O.C. (1884). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part VIII: The order Theropoda" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 27 (160): 329–340.

- ^ a b c d e f Gilmore, C.W. (1920). "Osteology of the carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus". Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 110: 1–154.

- ^ a b Madsen, J.H.; Welles, S.P. (2000). Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda): A Revised Osteology. Utah Geological Survey. pp. 1–80. ISBN 1557913803.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rowe, T.; Gauthier, J. (1990). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (ed.). The Dinosauria. University of California Press. pp. 151–168. ISBN 0520067266.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Britt, B.B.; Miles, C.A.; Cloward, K.C.; Madsen, J.H. (1999). "A juvenile Ceratosaurus (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from Bone Cabin Quarry West (Upper Jurassic, Morrison Formation), Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19 (Supplement to 3): 33A.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Foster, John (2007). "Gargantuan to Minuscule: The Morrison Menagerie, Part II". Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 162–242. ISBN 0253348706.

- ^ Tykoski, R.S.; Rowe, T. (2004). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (ed.). The Dinosauria: Second Edition. University of California Press. pp. 47–70. ISBN 0520242092.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Glut, D.F. (1997). "Ceratosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company. pp. 266–270. ISBN 0899509177.

- ^ a b Paul, Gregory S. (1988). "Ceratosaurs". Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster. pp. 274–279. ISBN 0671619462.

- ^ Madsen JH, Welles SP. Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria, Therapoda), a Revised Osteology. Miscellaneous Publication. Utah Geological Survey. ISBN 1-55791-380-3

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ^ Bakker RT, Bir G (2004). "Dinosaur Crime Scene Investigations". In Currie PJ, Koppelhus EB, Shugar MA, Wright JL (ed.). Feathered Dragons. Indiana University Press. pp. 301–342. ISBN 0-253-34373-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Dinosaurs and the media". The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 675–706. ISBN 0-253-33349-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)