Fobos-Grunt

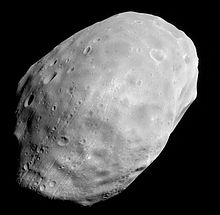

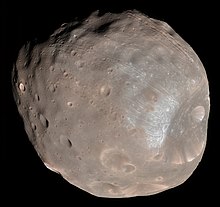

Fobos-Grunt (Russian: Фобос-Грунт, literally Phobos-Soil) is a failed[1] sample return mission to Phobos, one of the moons of Mars. Launched on November 9 local time, or the 8th for GMT, in 2011, it went into low Earth orbit awaiting resolution of a technical difficulty that has prevented it from leaving Earth orbit.[2] Funded by the Russian space agency Roscosmos and developed by NPO Lavochkin and the Russian Space Research Institute, Fobos-Grunt is the first Russian-led interplanetary mission since the failed Mars 96. The spacecraft is also carrying the Chinese Mars orbiter Yinghuo-1 and the tiny Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment funded by the Planetary Society.[3]

Lift-off occurred successfully at 02:16 of local time on 9 November 2011 (equivalent to 20:16 GMT on 8 November 2011) from Baikonur Cosmodrome, but the spacecraft failed to depart Earth orbit shortly afterwards.[4] The spacecraft was scheduled to reach Mars' orbit in September 2012 and land on Phobos in February 2013. The return vehicle, carrying up to 200 g of soil from Phobos, would then be expected back on Earth in August 2014.

Fobos-Grunt was designed to become the first spacecraft to return a macroscopic extraterrestrial sample from a planetary body since Luna 24 in 1976,[5] and the first Russian interplanetary mission since 1986.[6] However, as it hasn't succeeded in leaving Earth orbit for Mars, the 13.2 metric tonne spacecraft may undergo Earth re-entry in the near future.[2]

Project history

Fobos-Grunt is a space probe designed primarily to return 200 g (7 ounces) of Phobos to Earth.[7] It launched successfully into Earth orbit in November 2011, but did not launch to Mars like it was supposed to.[7] Working in support of the Russian mission, an ESA tracking station in Perth, Australia managed to establish contact with the probe.[8] The spacecraft's transmitter was switched on and a signal was received by the station's 15 m dish antenna.[8].

Development

The Fobos-Grunt project began in 1999, when the Russian Space Research Institute and NPO Lavochkin, the main developer of Soviet and Russian interplanetary probes, initiated a 9 million rouble feasibility study into a Phobos sample-return mission. The initial spacecraft design was to be similar to the probes of the Phobos program launched in the late 1980s.[9] Development of the spacecraft started in 2001 and the preliminary design was completed in 2004.[10] For years, the project stalled as a result of low levels of financing of the Russian space program. This changed in the summer of 2005, when the new government plan for space activities in 2006–2015 was published. Fobos-Grunt was now made one of the program's flagship missions. With substantially improved funding, the launch date was set for October 2009. The 2004 design was revised a couple of times and international partners were invited to join the project.[9] In June 2006, NPO Lavochkin announced that it began manufacturing and testing the development version of the spacecraft's onboard equipment.[11]

On 26 March 2007, Russia and China signed a cooperative agreement on the joint exploration of Mars, which included sending China's first interplanetary probe Yinghuo-1 to Mars together with the Fobos-Grunt spacecraft.[12] Compared to the main spacecraft, Yinghuo-1 weighs 115 kg (250-pound) and focused on Mars itself.[7] It would be released by the main spacecraft into a Mars orbit.

Skipped 2009 launch

The October 2009 launch date could not be achieved due to delays in the spacecraft development. During 2009, officials admitted that the schedule was very tight, but still hoped until the last moment that a launch could be made.[13] On 21 September the mission was officially announced to be delayed until the next launch window in 2011.[14][15][16][17] A main reason for the delay was difficulties encountered during development of the spacecraft's onboard computers. While the Moscow-based company Tehkhom provided the computer hardware on time, the internal NPO Lavochkin team responsible for integration and software development fell behind schedule.[18] The retirement of NPO Lavochkin's head Valeriy N. Poletskiy in January 2010 was widely seen as linked to the delay of Fobos-Grunt. Viktor Khartov was appointed the new head of the company. During the extra development time resulting from the delay, a Polish-built drill was added to the Phobos lander as a back-up soil extraction device.[19]

2011 Launch

The spacecraft arrived at Baikonur on 17 October 2011 and was transported to Site 31 for pre-launch processing.[20] The Zenit-2SB41 rocket carrying Fobos-Grunt successfully lifted off from Baikonur Cosmodrome at 20:16 GMT on 8 November 2011.[21] The Zenit booster inserted the spacecraft into an initial 207 km × 347 km (129 mi × 216 mi) elliptical based orbit with the inclination 51.4 degrees.[22]

Two firings of the main propulsion unit in Earth orbit are required to send the spacecraft onto the interplanetary trajectory. Since both engine ignitions will take place outside the range of Russian ground stations, the project participants asked volunteers around the world to take optical observations of the burns, e.g. with telescopes, and timely report the results to enable more accurate prediction of the mission flight path upon entry into the range of Russian ground stations.[23]

Post-launch

1. Baikonour launch

2. First Burn

3. Spent fuel tank ejected

4. Second Burn (Departure to Martian system)

It was expected that after 2.5 hours and 1.7 revolutions in the initial orbit, the autonomous main propulsion unit (MDU), derived from the Fregat upper stage, would conduct its firing to insert the spacecraft into the elliptical orbit (250 km x 4,150-4,170 km) with a period of about 2.2 hours. After the completion of the first burn, the external fuel tank of the propulsion unit was expected to be jettisoned, with ignition for a second burn to depart Earth orbit scheduled for one orbit, or 2.1 hours, after the end of the first burn.[22][24][25] The propulsion module constitutes the cruise-stage bus of Fobos-Grunt. According to original plans, Mars orbit arrival had been expected during September 2012 and the return vehicle was scheduled to reach Earth in August 2014.[26][27]

However, following what would have been the planned end of the first burn the spacecraft could not be located in the target orbit. The spacecraft was subsequently discovered to still be in its initial parking orbit,[4] and it was determined that the burn had not taken place.[28] One reason suggested for this behavior by According to Vladimir Popovkin, the head of the Russian Federal Space Agency (Roscosmos), as reported by the BBC, is that spacecraft did not fire its engines because it could not find stars to orient itself correctly.[3] Initially, they had about three days from launch to rescue it until the batteries ran out.[7] It was then established that its solar panels deployed, giving engineers more time to restore control of the spacecraft. It was soon discovered the spacecraft was adjusting its orbit, changing its expected re-entry from late November or December, to as late as early 2012.[29] Even though it had not been contacted, the spacecraft seemed to be actively adjusting its perigee (the point it is closest to Earth in its orbit).[30][31][29]

By 22 November 2011, attempts to establish connection with the probe were unsuccessful.[32] If the probe is not restarted by late November, it will miss the launch window and it will be no longer possible for it to reach the Martian system (the probe is not expected to survive until the next launch window, which will open in two years). Roscosmos spokesman admitted on November 22nd that chances of rescuing the mission were very slim.[32]

November 22 developments

European Space Agency, ESA, directed its ground stations in Kourou, French Guiana; Perth, Australia; and Maspolamas, Canary Islands; to conduct last attempts to communicate with Fobos-Grunt on November 22. A total five communications sessions with a station in Perth were planned during consequent orbits of the spacecraft at 00:25, 01:57, 03:32, 08:16, 09:49 Moscow Time, each lasting six-seven minutes. A station in Kourou would have communication opportunities from 21:52 to 21:59 Moscow Time.

One eyewitness in San Francisco described the spacecraft emitting flashes with peaks every 20 seconds -- a clear indication of tumbling. In the meantime, at 18:44 GMT, the second stage of the Zenit rocket, which flawlessly delivered Fobos-Grunt into its initial orbit, reentered the Earth atmosphere over Australia's Northern Territory. Unlike its payload, the stage's descent was steady and predictable.

November 23 developments

During the night from November 22 to November 23 Moscow Time (20:25 GMT on November 22), Fobos-Grunt finally communicated with a ground station in Perth, Australia, the European Space Agency, which operates the facility, announced. The contact was apparently established during first of five passes of the spacecraft over Perth from 00:25 to 01:11 Moscow Time. According to ESA, the critical communication session took place from 20:21 to 20:28 GMT on November 22, as the Perth station transmitted telecommands provided by NPO Lavochkin. A small, side antenna in Perth with a diameter of only 1.3 meters and rigged with a special cone was used to send a weak three-watt signal to the spacecraft, to turn on its transmitter.

"Owing to its very low altitude, it was expected that our station would only have Fobos-Grunt in view for six to ten minutes during each orbit, and the fast overhead pass introduced large variations in the signal frequency," Wolfgang Hell, the Fobos-Grunt Service Manager at ESOC, was quoted by ESA web site. Despite these difficulties, it was a success: the signals commanded the spacecraft's transmitter to switch on, sending a signal down to the station's 15-meter dish antenna.

Due to technical limitations of the ground station in Perth, it could only receive a carrier signal from the spacecraft containing no telemetry. Still, the reception of the signal confirmed that at least some radio systems onboard had been operational and provided hope that a full control over the mission could be established. Data received from Fobos-Grunt was then transmitted from Perth to Russian mission controllers via ESA's Space Operations Centre,Darmstadt, Germany, for analysis.

Even NPO Lavochkin, the spacecraft manufacturer, which has not provided any information on the mission since its launch, posted a message on its web site, saying that a "responding radio signal" had been received from Fobos-Grunt.

During its successful contact with the Perth station, the spacecraft was in sunlight, while during communication attempts from Baikonur, Fobos-Grunt was in the shadow of the Earth. This factor could affect power supply to the communication gear, sources said.

One source quoted by the press said that the facility in Perth could be reconfigured to receive telemetry from the spacecraft by the next pass of the probe within its communication range. The station's antenna range had already been expanded to facilitate communications with a low-flying vehicle.

According to a representative of the European Space Agency in Moscow, the spacecraft would be in the range of the same station in Perth on November 24 from 00:15 to 00:23 Moscow Time and from 01:48 to 01:56 Moscow Time. ESA then officially announced that additional communication slots had been available on November 23 at 20:21–20:28 GMT and 21:53–22:03 GMT.

November 24 developments

Around 01:00 Moscow Time (4 p.m. EST on November 23), a poster on the forum of the Novosti Kosmonavtiki magazine reported that the telemetry from the spacecraft had been received as well. A data set was reportedly downlinked to a European ground station and transferred to NPO Lavochkin for analysis. Shortly thereafter, the official Russian media quoted a European representative in Moscow as saying that ESA ground station in Perth had received telemetry from the spacecraft. According to Novosti Kosmonavtiki's Igor Lissov, an emergency telemetry frame from the radio-system onboard the cruise stage, PM, had been received, confirming normal power supply and the operation of the communication gear. During the next communication pass starting at 03:30 Moscow Time, ground controllers hoped to downlink telemetry via probe's main flight control computer, BKU, essentially a brain of the mission. According to an ESA representative in Perth, quoted by RIA Novosti, five passes of Phobos-Grunt over Perth had taken place during November 24, beginning at 00:25, 01:57, 03:32, 08:16 and 09:49 Moscow Time. It is known that no attempts to communicate with the spacecraft was made during a second pass, starting at 01:57, since the spacecraft would be the range of the ground station less time than during other windows. However, a successful contact with the spacecraft at 08:16 had been confirmed. Further attempts were made, but this time without success. According to BBC, only first of five passes yielded data from the spacecraft.

In the meantime, Space Forces of Russia confirmed that Phobos-Grunt had been expected to reenter the Earth atmosphere in January-February 2012. At the time, the spacecraft was in a 319 by 205-kilometer orbit with an inclination 51.41 degrees toward the Equator. Radar data was now showing a steady decay of the probe's orbit, without previously seen minor increases in orbital altitude.

Re-entry risk

Roughly 7.5 metric tonnes of highly toxic hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide are on board, according to the head of Roscosmos.[7][2] It is mostly fuel for the spacecraft's upper stage. The amount of fuel is nearly 20 times the amount that was on board the American spy satellite USA-193, which was shot down before reentry by the U.S. in February 2008. These compounds, with melting points of 2 °C and -11.2 °C, are normally kept in liquid form; if the probe is not rescued but they remain liquid, they are expected to burn out during reentry.[7] NASA veteran James Oberg said the hydrazine and nitrogen teroxide "could freeze before ultimately entering".[2] If Fobos-Grunt is not salvaged, it may be the most dangerous object to fall from orbit.[2] However, the head of Roscomos says the probability of parts reaching the Earth is "highly unlikely", and that spacecraft would be destroyed during re-entry.[7]

Contact

On 23 November 2011, a signal from the probe was picked up by the European Space Agency`s tracking station in Perth, Australia, after it had sent the probe the command to turn on one of its transmitters. The European Space Operations Centre (Esoc) in Darmstadt reported that the contact was made at 2025 GMT on 22 November 2011 after some modifications had been to the 15m dish facility in Perth to improve its chances of getting a signal.[33] No telemetry was received in this communication.[34] It remains unclear whether the communications link will be sufficient to command the spacecraft to switch on its engines to take it on its intended trajectory toward Mars[35]. Roscosmos officials have said that a window of opportunity to salvage Fobos-Grunt would close in early December.[35]

An eyewitness in San Francisco described the spacecraft emitting flashes with peaks every 20 seconds, an indication of tumbling.[36] However, Roscosmos's top officials believe Fobos-Grunt to be functional, stably oriented and charging batteries through its solar panels.[34] The prospects for the original mission are still unclear.[37]

On 24 November, telemetry was received again.[38]

Purpose

Fobos-Grunt is an interplanetary probe that includes a lander to study Phobos and a sample return vehicle to return a soil sample (about 200 g (7.1 oz))[39] to Earth. It will also study Mars from orbit, including its atmosphere and dust storms, plasma and radiation.

Science goals

- Delivery of samples of Phobos soil to Earth for scientific research of Phobos, Mars and Martian vicinity;

- In situ and remote studies of Phobos (to include analysis of soil samples);

- Monitoring the atmospheric behavior of Mars, including the dynamics of dust storms;

- Studies of the vicinity of Mars, including its radiation environment, plasma and dust;[26]

- Study of the origin of the Martian satellites and their relation to Mars;

- Study of the role played by asteroid impacts in the formation of terrestrial planets;

- Search for possible past or present life (biosignatures);[40]

- Study the impact of a three year interplanetary round-trip journey to extremophile microorganisms in a small sealed capsule (LIFE experiment).[41]

Mission plan

This is a description of the original mission plan.

Journey

The spacecraft's journey to Mars would take about ten months. After arriving in Mars orbit, the main propulsion unit (MDU) and the transfer truss separate and the Chinese Mars orbiter would be released. Fobos-Grunt would then spend several months studying the planet and its moons from orbit, before landing on Phobos. The timeline with its 2011 launch, was for arrival in Mars orbit in October 2012 and landing on Phobos in February 2013.[27]

The planned landing site is a region from 5°S to 5°N, 230° to 235°E.[42]

On Phobos

Soil sample collection would begin immediately after the lander has touched down on Phobos, with normal collection lasting 2–7 days. An emergency mode exists for the case of communications breakdown, which enables the lander to automatically launch the return rocket to deliver the samples to Earth.[43]

A robotic arm would collect samples, which can be up to 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) in diameter. At the end of the arm, there is a pipe-shaped tool which splits to form a claw. The tool contains a piston which will push the sample into a cylindrical container. A light-sensitive photo-diode will confirm whether material collection was successful and will also allow visual inspection of the digging area. The sample extraction device should perform 15 to 20 scoops yielding a total of 3 to 5.5 ounces (85 to 156 g) of soil.[43] The samples are loaded into a capsule which is then moved inside a special pipeline into the descent module by inflating an elastic bag within the pipe with gas.[10][44] Because the characteristics of Phobos soil are uncertain, the lander includes another soil-extraction device, a Polish-built drill, which will be used in case the soil turns out to be too rocky for the main scooping device.[5][19]

The return stage is mounted on top of the lander. It will need to accelerate to 35 km/h (22 mph) to escape Phobos' gravity. In order to avoid harming the experiments remaining at the lander, the return stage will only ignite its engine once the vehicle has been vaulted to a safe height by springs. It will then begin maneuvers for the eventual trip to Earth, where it is expected to arrive in August 2014.[43]

After the departure of the return stage, the lander's experiments will continue in situ on Phobos' surface for a year. To conserve power, mission control will turn these on and off in a precise sequence. The robotic arm will place more samples in a chamber that will heat it and analyze its spectra. This analysis might determine the presence of volatile compounds, such as water.[43]

Sample return to Earth

The return stage with soil samples from Phobos was scheduled to be back near Earth in August 2014. An 11-kg[45] descent vehicle containing the capsule with soil samples (up to 0.2 kg (0.44 lb)) will be released on direct approach to Earth at 12 km/s (7.5 mi/s). Following the aerodynamic braking to 30 m/s (98 ft/s) the conical-shaped descent vehicle will perform a hard landing without a parachute within the Sary Shagan test range in Kazakhstan.[44] The vehicle does not have any radio equipment.[5] Ground-based radar and optical observations will be used to track the vehicle's return.[46]

Equipment

Spacecraft instruments

- TV system for navigation and guidance[47]

- Gas-Chromatograph package:[45]

- Thermal Differential Analyzer

- Gas-Chromatograph

- Mass-Spectrometer

- Gamma ray spectrometer[48]

- Neutron spectrometer[48]

- Alpha X spectrometer[48]

- Seismometer[48]

- Long-wave radar[48]

- Visual and near-infrared spectrometer[48]

- Dust counter[48]

- Ion spectrometer[48]

- Optical solar sensor[49]

Ground control

The Mission Control Center was located at the Center for Deep Space Communications (Национальный центр управления и испытаний космических средств Template:Ref-ru, Євпаторійський центр дальнього космічного зв'язку Template:Ref-uk) equipped with RT-70 radio telescope near Yevpatoria in the Crimea, Ukraine.[50] Russia and Ukraine agreed in late October 2010 that the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, would control the probe.[51]

Communications with the spacecraft on the initial parking orbit are described in a two-volume publication on «Fobos-Grunt» as follows (excerpt, as translated from Russian):[52]

2-7 Organization of the spacecraft (SC) control

Main tasks of providing the control of the SC

Trans Martian injection phase

Organization of interoperation with the SC is characterized by practical inability to provide two-way communications with the SC, mainly in the initial parking orbit. This means that the first maneuver along the powered flight path between the parking orbit and the transfer orbit is performed by the SC automatically. The correct execution of the first orbit correction maneuver requires that the following conditions are met:

- launch to the initial orbit is performed correctly;

- initiation of the burn is synchronized with a preset moment of Moscow Decree Time for a specific launch date.

To meet the second condition a non-volatile clock, counting the Moscow Decree Time and Date with adequate precision, is used with its dedicated power source on board the SC.

Monitoring of the SC flight starts after the flight computer is switched on by the contacts triggered by the SC separation followed by the flight computer initializing the onboard systems. The initialization takes 30 to 60 seconds. Then РПТ111 device is switched on, through which telemetry about the SC condition is transmitted to Earth. Starting with receiving this data the mission control center assumes «Fobos-Grunt» mission control.

While in parking orbit within the range of Russian ground stations, one-way monitoring of the SC flight is performed on the telemetry channel via РПТ111 transmitter, and the trajectory measurements are performed using 28Г6 device.

After reaching the transfer orbit the visibility areas are increased, angular velocity of the SC movement relative to the ground stations is decreased, an opportunity becomes available to establish two-way communications with the SC via onboard radiosystem of the cruise stage.

Development

Main participants

The main contractor of the project is NPO Lavochkin, which is responsible for the space mission component development. Chief Designer of Phobos Grunt at Lavochkin is Maksim Martynov.[53] Phobos soil sampling and downloading were developed by the GEOHI RAN Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Vernadski Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical chemistry) and the integrated scientific studies of Phobos and Mars by remote and contact methods are responsibility of the Russian Space Research Institute,[26] where the lead scientist of the mission is Alexander Zakharov.[54]

Budget

The cost of the spacecraft is 1.5 billion rubles ($64.4 million).[10] Project funding for the timeframe 2009–2012, including post-launch operations is about 2.4 billion rubles.[16] Total cost of the mission is 5 billion rubles ($163 million). In comparison, the more ambitious NASA/ESA joint Mars sample return mission is expected to cost around $8.5 billion.[55]

Revival of interplanetary missions

Fobos-Grunt is the first Russian interplanetary mission since Mars 96, which suffered a launch failure. The last Russian or Soviet interplanetary mission that was successfully launched was the second probe of the Phobos program in 1988.[54] Fobos-Grunt is the first sample return mission to the natural satellite of another planet conducted by mankind.[56] If successful, Fobos-Grunt could pave way to a number of Russian interplanetary missions, including missions to the moons of Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus, and asteroid and comet sample return missions.[57]

The Russian Federal Space Agency has said 90% of Phobos Grunt is made of new and untested elements. The new instruments are being tested and will be tested during the flight.[51] According to lead scientist Alexander Zakharov, the entire spacecraft and most of the instruments are new, although they do draw on the heritance of the three successful Luna sample-return missions of the 1970s.[55] Zakharov has described the Phobos sample return project as "very difficult", possibly "the most difficult interplanetary one to date."[54]

Partners

The Chinese Mars probe Yinghuo-1 will be sent together with Fobos-Grunt.[58] In late 2012, after a 10-11.5 month cruise, Yinghuo-1 will separate and enter a 800×80,000 km equatorial orbit (5° inclination) with a period of three days. The spacecraft is expected to remain on Martian orbit for one year. Yinghuo-1 will focus mainly on the study of the external environment of Mars. Space center researchers will use photographs and data to study the magnetic field of Mars and the interaction between ionospheres, escape particles and solar wind.[59]

A second Chinese payload, the Soil Offloading and Preparation System (SOPSYS), is to be integrated into the instruments of the lander. SOPSYS is a microgravity grinding tool developed by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.[60][61]

Another payload on Fobos-Grunt is an experiment from the Planetary Society called Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment, or LIFE, which will send 10 types of microorganisms and a natural soil colony of microbes on the three-year round trip. The results may fuel the debate about whether meteorite-riding organisms can spread life throughout the solar system.[13][62]

Two MetNet Mars landers, developed by the Finnish Meteorological Institute, were planned to be included as a payload to the Fobos-Grunt mission.[63][64] Due to delays in MetNet development, the landers were not ready for the previous launch date of Fobos-Grunt, 2009. For the 2011 launch window, which is not as suitable as the 2009 one, weight constraints on the Fobos-Grunt spacecraft required dropping the MetNet landers from the mission.[16]

The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences has also installed its own radiation measurement experiment on Fobos-Grunt.[65]

Critiques

Barry E. DiGregorio, the director of the International Committee Against Mars Sample Return, criticised the LIFE experiment carried by Fobos-Grunt as a violation of the Outer Space Treaty due to the possibility of contamination of Phobos or Mars with the microbial spores and live bacteria it contains.

While Fobos-Grunt lands on and returns from Phobos, it might lose control and crash land on Mars.[66] It is speculated that the heat-resistant extremophile bacteria would survive such a crash, on the basis that Microbispora bacteria survived the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.[67]

However, according to Fobos-Grunt Chief Designer Maksim Martynov, the probability of the probe accidentally reaching the surface of Mars is much lower than the maximum specified for Category III missions, the type assigned to Fobos-Grunt and defined in COSPAR's planetary protection policy (in accordance with Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty).[44][68]

References

- ^ http://en.rian.ru/science/20111124/169002288.html

- ^ a b c d e Vladimir Ischenkov - Russian scientists struggle to save Mars moon probe (November 9, 2011) - Associated Press

- ^ a b Jonathan Amos (9 November 2011). "Phobos-Grunt Mars probe loses its way just after launch". BBC.

- ^ a b Molczan, Ted (9 November 2011). "Phobos-Grunt - serious problem reported". SeeSat-L. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Daring Russian Sample Return mission to Martian Moon Phobos aims for November Liftoff". Universe Today. 2011-10-13.

- ^ "Jonathan's Space Report No. 650 2011 Nov 16".

- ^ a b c d e f g http://www.space.com/13618-russia-phobos-grunt-mars-spacecraft-silent.html

- ^ a b http://www.esa.int/esaCP/SEM4NEZW5VG_index_0.html ESA tracking station establishes contact with Russia’s Mars mission

- ^ a b Harvey, Brian (2007). "Resurgent - the new projects". The Rebirth of the Russian Space Program (1st ed.). Germany: Springer. pp. 326–330. ISBN 9780387713540.

- ^ a b c Zaitsev, Yury (14 July 2008). "Russia to study Martian moons once again". RIA Novosti.

- ^ "Russia to test unmanned lander for Mars moon mission". RIA Novosti. 2010-09-09.

- ^ "China to launch probe to Mars with Russian help in 2009". RIA Novosti. 2008-12-05.

- ^ a b Zak, Anatoly (2008-09-01). "Mission Possible - A new probe to a Martian moon may win back respect for Russia's unmanned space program". AirSpaceMag.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ "Fobos-Grunt probe launch is postponed to 2011" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 2009-09-21. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ "Russia delays Mars probe launch until 2011: report". Space Daily. 16 September 2009.

- ^ a b c Zak, Anatoly. "Preparing for flight". Russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (2009-04). "Russia to Delay Martian Moon Mission". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Industry Insiders Foresaw Delay of Russia's Phobos-Grunt". Space News. 2009-10-05.

- ^ a b "Difficult rebirth for Russian space science". BBC News. 2010-06-29.

- ^ Phobos-Grunt arrives to Baikonur

- ^ . RIA Novosti. 2011-11-09 http://en.rian.ru/science/20111109/168527324.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Mission profile Phobos-Soil project

- ^ We need your support in the project "Phobos-Soil", because Phobos-soil project

- ^ "Phobos-Grunt to be launched to Mars on Nov 8". Interfax News. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ "Fobos-Grunt space probe is moved to a refueling station". Roscosmos. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-21.Template:Ref-ru

- ^ a b c "Phobos-Grunt". European Space Agency. October 25, 2004. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ a b "Timeline for the Phobos Sample Return Mission (Phobos Grunt)". Planetary Society. October 27, 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ "Маршевая двигательная установка станции "Фобос-Грунт" не сработала" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ a b David Warmflash, M.D. - Phobos-Grunt’s Mysterious Thruster Activation: A Function of Safe Mode or Just Good Luck? (November 16, 2011) - Universe Today

- ^ http://english.ruvr.ru/2011/11/15/60435756.html

- ^ http://english.ruvr.ru/2011/11/14/60345638.html

- ^ a b "Роскосмос признал, что шансов реализовать миссию "Фобос-Грунт" практически не осталось" (in Russian).

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (23 November 2011). "Signal picked from Russia's stranded Mars probe". BBC News.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (23 November 2011). "It's alive! Russia's Phobos-Grunt probe phones home". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ a b http://www.spacenews.com/civil/111123-esa-establishes-contact-with-phobos-grunt-spacecraft.html ESA Makes Contact with Russia’s Stranded Phobos-Grunt Spacecraft Cite error: The named reference "spacenews" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (23 November 2011). "November 22 developments". Russianspaceweb.com.

- ^ "Europeans report contact with Russia's Mars probe". Msnbc.com. 23 November 2011.

- ^ "ESA receives telemetry from Russian Mars probe". Ria Novosti. 24 November 2011.

- ^ Fobos-Grunt sent to Baikonur Template:Ref-ru

- ^ Korablev, O. "Russian programme for deep space exploration" (PDF). Space Research Institute (IKI). p. 14.

- ^ "Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment (LIFE)". The Planetary Society.

- ^ "Phobos Flyby Images: Proposed Landing Sites for the Forthcoming Phobos-Grunt Mission". Science Daily. 15 March 2010. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d Zak. "Mission Possible".

- ^ a b c "Russia resumes missions to outer space: what is after Phobos?".Template:Ref-ru

- ^ a b Phobos Soil - Spacecraft European Space Agency

- ^ The mission scenario of the Phobos-Grunt project Anatoly Zak

- ^ "Optico-electronic Instruments for the Phobos-Grunt Mission". Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harvey, Brian (2007). "Resurgent - the new projects". The Rebirth of the Russian Space Program (1st ed.). Germany: Springer. ISBN 9780387713540.

- ^ "Optical Solar Sensor". Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ Russian spacecraft for Fobos-Grunt program to be controlled from Yevpatoria, Kyiv Post (June 25, 2010)

- ^ a b "Russia's Phobos Grunt to head for Mars on November 9". Itar Tass. 25 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ «Fobos-Grunt» sample return mission materiel.Template:Ref-ru

- ^ Biography of Maksim MartynovTemplate:Ref-ru

- ^ a b c "Mars Moon Lander to Return Russia to Deep Space". The Moscow Times. 08 Nov 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Russia takes aim at Phobos". Nature. 2011-11-04.

- ^ LIVE: Zenit-2 set to launch Fobos-Grunt sample return mission to Phobos Nasaspaceflight

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (April 15, 2008). "Russian space program: a decade review (2000–2010)". Russian Space Web.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (May 21, 2007). "With a Russian hitch-hike, China heading to Mars". NASAspaceflight.

- ^ "China and Russia join hands to explore Mars". People's Daily Online. May 30, 2007. Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- ^ Zhao, Huanxin (27 March 2007). "Chinese satellite to orbit Mars in 2009". China Daily.

- ^ "HK triumphs with out of this world invention". HK Trader. 1 May 2007.

- ^ "LIFE Experiment: Phobos". The Planetary Society.

- ^ "MetNet Mars Precursor Mission". Finnish Meteorological Institute.

- ^ "Space technology – a forerunner in Finnish-Russian high-tech cooperation". Energy & Enviro Finland. 17 October 2007.

- ^ "Проект "Люлин-Фобос" - "Радиационно сондиране по трасето Земя-Марс в рамките на проекта "Фобос-грунт"". Международен проект по програмата за академичен обмен между ИКСИ-БАН и ИМПБ при АН на Русия - (2011-2015)". Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

- ^ DiGregorio, Barry E. (2010-12-28). "Don't send bugs to Mars". New Scientist. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ McLean, R; Welsh, A; Casasanto, V (2006). "Microbial survival in space shuttle crash". Icarus. 181 (1): 323–325. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.002. PMC 3144675. PMID 21804644.

- ^ "COSPAR Planetary Protection Policy".

Further reading

- M. Ya. Marov, V. S. Avduevsky, E. L. Akim, T. M. Eneev, R. S. Kremnevich, S. D. Kulikovich, K. M. Pichkhadzec, G. A. Popov, G. N. Rogovshyc (2004). "Phobos-Grunt: Russian sample return mission". Advances in Space Research. 33 (12): 2276–2280. Bibcode:2004AdSpR..33.2276M. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(03)00515-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Galimov, E. M. (2010). "Phobos sample return mission: Scientific substantiation". Solar System Research. 44: 5. doi:10.1134/S0038094610010028.

- Zelenyi, L. M.; Zakharov, A. V. (2010). "Phobos-Grunt project: Devices for scientific studies". Solar System Research. 44 (5): 359. doi:10.1134/S0038094610050011.

- Rodionov, D. S.; Klingelhoefer, G.; Evlanov, E. N.; Blumers, M.; Bernhardt, B.; Gironés, J.; Maul, J.; Fleischer, I.; Prilutskii, O. F. (2010). "The miniaturized Möessbauer spectrometer MIMOS II for the Phobos-Grunt mission". Solar System Research. 44 (5): 362. doi:10.1134/S0038094610050023.