Leishmania

| Leishmania | |

|---|---|

| |

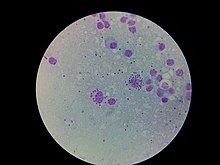

| Leishmania donovani in bone marrow cell. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Genus: | Leishmania

|

| Binomial name | |

| Leishmania Ross, 1903

| |

| Species | |

|

L. aethiopica | |

Leishmania /liːʃˈmeɪnɪə/ is a genus of trypanosomatid protozoa and is the parasite responsible for the disease leishmaniasis.[1][2] It is spread through sandflies of the genus Phlebotomus in the Old World, and of the genus Lutzomyia in the New World. At least 93 sandfly species are proven or probable Leishmania vectors worldwide.[3] Their primary hosts are vertebrates; Leishmania commonly infects hyraxes, canids, rodents, and humans.

History

The parasite was named in 1903 after the Scottish pathologist William Boog Leishman.

Epidemiology

Leishmania currently affects 12 million people in 98 countries. There are ~ 2 million new cases each year. 21 species are known to cause disease in humans.

Structure

Leishmania are unicellular eukaryotes having well-defined nucleus and other cell organelles including kinetoplast and flagellum. Depending on the stages of life cycle they exists in two structural variants, as follows:[4][5]

- Amastigote form found in the mononuclear phagocyte and circulatory systems of humans. It is an intracellular and non-motile form, being devoid of external flagellum. The short flagellum is embedded at the anterior end without projecting out. It is oval in shape, and measures 3–6 µm in length and 1–3 µm in breadth. The kinetoplast and basal body lie towards the anterior end.

- Promastigote form found in the alimentary tract of sandfly. It is an extracellular and motile form. It is considerably larger and highly elongated, measuring 15-30 µm in length and 5 µm in width. It is spindle-shaped, tapering at both ends. A long flagellum (about the body length) is projected externally at the anterior end. The nucleus lies at the centre, and in front of it are kinetoplast and basal body.

Evolution

The details of the evolution of this genus are debated, but it appears that Leishmania evolved from an ancestral trypanosome lineage. The oldest lineage is that of the Bodonidae, followed by Trypanosoma brucei, the latter being confined to the African continent. Trypanosoma cruzi groups with trypanosome from bats, South American mammals and kangaroos suggest an origin in the Southern Hemisphere. These clades are only distantly related.

The remaining clades in this tree are Blastocrithidia, Herpetomonas and Phytomonas. The four genera Leptomonas, Crithidia, Leishmania and Endotrypanum form the terminal branches, suggesting a relatively recent origin. Several of these genera may be polyphetic and may need further division.[6]

The origins of genus Leishmania itself are unclear.[7][8] One theory proposes an African origin, with migration to the Americas. Another proposes migration from the Americas to the Old World via the Bering Strait land bridge approximately 15 million years ago. A third theory proposes a palearctic origin.[9] Such migrations would entail subsequent migration of vector and reservoir or successive adaptations along the way. A more recent migration is that of L. infantum from Mediterranean countries to Latin America (known as L. chagasi), since European colonization of the New World, where the parasites picked up their current New World vectors in their respective ecologies.[10] This is the cause of the epidemics now evident. One recent New World epidemic concerns foxhounds in the USA.[11]

Leishmania may have evolved in the Neotropical region.[12]

Sauroleishmania were originally defined on the basis that they infected reptiles (lizards) rather than mammals. Molecular studies have cast doubts on this basis for classification and they have been moved to subgenus status within Leishmania. It appears that this subgenus evolved from a group that originally infected mammals.[13]

Taxonomy

There are about 35 species in this genus. The status of several of these is disputed and for this reason the final number may differ from this estimate. At least 20 species infect humans.

There are (at least) three subgenera: Leishmania, Sauroleishmania and Viannia. The division into the two subgenera (Leishmania and Viannia) was made by Lainson and Shaw in 1987 on the basis of their location within the insect gut. The species in the Viannia subgenus develop in the hind gut: L. (V.) braziliensis has been proposed as the type species for this subgenus, This division has been confirmed by all subsequent studies.

Endotrypanum is also closely related and may also be moved to subgenus status within Leishmania. The subgenus Endotypanum is unique in that the parasites of this subgenus infect the erythrocytes of their host (sloths). The species in this subgenus are confined for the Central and South America.[14]

Sauroleishmania was originally described by Ranquein 1973 as a separate genus but molecular studies suggest that this is actually a subgenus rather than a separate genus.

A proposed division of the Leishmania is into Euleishmania and Paraleishmania.[15] The proposed groups Paraleishmania would include all the species in the genus Endotypanum and L. colomubensis, L. deanei, L. equatorensis and L. hertigi. The group Euleishmania would include those species currently placed in the subgenera Leishmania and Viannia. These groups may be accorded subgenus (or other) status at some point but their positions remains undefined at present.

Leishmania archibaldi may be the same species as Leishmania dononani.

Leishmania herreri may belong to the genus Endotypanum rather than to Leishmania.

Classification

Subgenus Leishmania

- Leishmania aethiopica

- Leishmania amazonensis

- Leishmania arabica

- Leishmania donovani

- Leishmania enrietti

- Leishmania gerbilli

- Leishmania hertigi

- Leishmania infantum

- Leishmania killicki

- Leishmania major

- Leishmania martiniquensis[16]

- Leishmania mexicana

- Leishmania siamensis

- Leishmania tropica

- Leishmania turanica

Subgenus Sauroleishmania

- Leishmania adleri

- Leishmania agamae

- Leishmania ceramodactyli

- Leishmania deanei

- Leishmania garnhami

- Leishmania gulikae

- Leishmania gymnodactyli

- Leishmania hemidactyli

- Leishmania hoogstraali

- Leishmania nicollei

- Leishmania senegalensis

- Leishmania tarentolae

Subgenus Viannia

- Leishmania braziliensis

- Leishmania colombiensis

- Leishmania equatorensis

- Leishmania guyanensis

- Leishmania lainsoni

- Leishmania naiffi

- Leishmania panamensis

- Leishmania peruviana

- Leishmania pifanoi

- Leishmania shawi

- Leishmania utingensis

The genus Endotrypanum is also included here as this may be reclassified as Leishmania

Genus Endotrypanum

- Endotrypanum monterogeii

- Endotrypanum schaudinni

Biochemistry and cell biology

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2011) |

The biochemistry and cell biology of Leishmania is similar to that of other kinetoplastids. They share the same main morphological features; a single flagellum which has an invagination, the flagellar pocket, at its base, a kinetoplast which is found in the single mitochondrion and a sub-pelicular array of microtubules which make up the main part of the cytoskeleton.

Lipophosphoglycan coat

Leishmania possess a lipophosphoglycan coat over the outside of the Leishmania cell. Lipophosphoglycan is a trigger for Toll-like receptor 2, a signalling receptor involved in triggering an innate immune response in mammals.

Structure

The precise structure of lipophosphoglycan varies depending on the species and life cycle stage of the parasite. The glycan component is particularly variable and different lipophosphoglycan variants can be used as a molecular marker for different life cycle stages. Lectins, a group of plant proteins which bind different glycans, are often used to detect these lipophosphoglycan variants. For example peanut agglutinin binds a particular lipophosphoglycan found on the surface of the infective form of Leishmania major.

Function

Lipophosphoglycan is used by the parasite to promote its survival in the host and the mechanisms by which the parasite does this center around modulating the immune response of the host. This is vital as the Leishmania parasites live within macrophages and need to prevent the macrophage from killing them. Lipophosphoglycan has a role in resisting the complement system, inhibiting the oxidative burst response, inducing an inflammation response and preventing natural killer T cells recognising that the macrophage is infected with the Leishmania parasite.

Pathophysiology

Leishmania cells have two morphological forms: promastigote (with an anterior flagellum)[17] in the insect host, and amastigote (without flagella) in the vertebrate host. Infections are regarded as cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral.

| Type | Pathogen | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous leishmaniasis (localised and diffuse) infections appear as obvious skin reactions. | The most common is the Oriental Sore (caused by Old World species L. major, L. tropica, and L. aethiopica). In the New World, the most common culprits is L. mexicana. | Cutaneous infections are most common in Afghanistan, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia and Syria. |

| Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (Espundia or Uta) infections will start off as a reaction at the bite, and can go via metastasis into the mucous membrane and become fatal. | L. braziliensis | Mucocutaneous infections are most common in Bolivia, Brazil and Peru. Mucocutaneous infections are also found in Karamay, China Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. |

| Visceral leishmaniasis infections are often recognised by fever, swelling of the liver and spleen, and anemia. They are known by many local names, of which the most common is probably Kala azar,[18][19] | Caused exclusively by species of the L. donovani complex (L. donovani, L. infantum syn. L. chagasi).[1] | Found in tropical and subtropical areas of all continents except Australia, visceral infections are most common in Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Nepal and Sudan.[1] Visceral leishmaniasis also found in part of China, such as Sichuan Province, Gansu Province and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. |

Intracellular mechanism of infection

The strategy of the pathogens like Leishmania to avoid destruction by the immune system and thrive is by 'hiding' inside a cell. This location enables it to avoid the action of the humoral immune response (because the pathogen is safely inside a cell and outside the open bloodstream), and furthermore it may prevent the immune system from destroying its host through non-danger surface signals which discourage apoptosis. The primary cell types Leishmania infiltrates are phagocytotic cells such as neutrophils and macrophages.[20]

Usually, a phagocytotic immune cell like a macrophage will ingest a pathogen within an enclosed endosome and then fill this endosome with enzymes which digest the pathogen. However, in the case of Leishmania, these enzymes have no effect, allowing the parasite to multiply rapidly. This uninhibited growth of parasites eventually overwhelms the host macrophage or other immune cell, causing it to die.[21]

Transmitted by the sandfly, the protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania major may switch the strategy of the first immune defense from eating/inflammation/killing to eating/no inflammation/no killing of their host phagocyte and corrupt it for their own benefit.[citation needed] They use the willingly phagocytosing polymorphonuclear neutrophil granulocytes (PMN) rigorously as a tricky hideout, where they proliferate unrecognized from the immune system and enter the long-lived macrophages to establish a “hidden” infection.[citation needed]

Uptake and survival

Upon microbial infection PMN move out from the bloodstream through the vessels’ endothelial layer, to the site of the infected tissue (dermal tissue after fly bite). They immediately initiate the first immune response and phagocytize the invader by recognition of foreign and activating surfaces on the parasite. Activated PMN secrete chemokines, IL-8 particularly, to attract further granulocytes and stimulate phagocytosis. Further Leishmania major increases the secretion of IL-8 by PMN. This mechanism is observed during infection with other obligate intracellular parasites as well. For microbes like these, there are multiple intracellular survival mechanisms. Surprisingly, the co-injection of apoptotic and viable pathogens causes by far a more fulminate course of disease than injection of only viable parasites.When the anti-inflammatory signal phosphatidylserine usually found on apoptotic cells, is exposed on the surface of dead parasites, Leishmania major switches off the oxidative burst,thereby preventing killing and degradation of the viable pathogen.

In the case of Leishmania, progeny are not generated in PMN, but in this way they can survive and persist untangled in the primary site of infection. The promastigote forms also release LCF (Leishmania chemotactic factor) to actively recruit neutrophils, but not other leukocytes, for instance monocytes or NK cells. In addition to that, the production of interferon gamma (IFN

Persistency and attraction

The lifespan of neutrophil granulocytes is quite short. They circulate in bloodstream for about 6 or 10 hours after leaving bone marrow, whereupon they undergo spontaneous apoptosis. Microbial pathogens have been reported to influence cellular apoptosis by different strategies. Obviously because of the inhibition of caspase3-activation Leishmania major can induce the delay of neutrophils apoptosis and extend their lifespan for at least 2–3 days. The fact of extended lifespan is very beneficial for the development of infection because the final host cells for these parasites are macrophages, which normally migrate to the sites of infection within 2 or 3 days. The pathogens are not dronish; instead they take over the command at the primary site of infection. They induce the production by PMN of the chemokines MIP-1

Silent phagocytosis Theory

To save the integrity of the surrounding tissue from the toxic cell components and proteolytic enzymes contained in neutrophils, the apoptotic PMN are silently cleared by macrophages. Dying PMN expose the "eat me"-signal phosphatidylserine which is transferred to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during apoptosis. By reason of delayed apoptosis the parasites that persist in PMN are taken up into macrophages, employing an absolutely physiological and non-phlogistic process. The strategy of this "silent phagocytosis" has the following advantages for the parasite:

- Taking up apoptotic cells silences macrophage killing activity leading to a survival of the pathogens.

- Pathogens inside of PMN have no direct contact to the macrophage surface receptors, because they can not see the parasite inside the apoptotic cell. So the activation of the phagocyte for immune activation does not occur.

However studies have shown this is unlikely the case as the pathogens are seen to leave apoptopic cells and there is no eveidence of macrophage uptake via this method.

Molecular biology

An important aspect of the Leishmania protozoan is its glycoconjugate layer of lipophosphoglycan (LPG). This is held together with a phosphoinositide membrane anchor, and has a tripartite structure consisting of a lipid domain, a neutral hexasaccharide, and a phosphorylated galactose-mannose, with a termination in a neutral cap. Not only do these parasites develop post-phlebotomus digestion but, it is thought to be essential to oxidative bursts, thus allowing passage for infection. Characteristics of intracellular digestion include an endosome fusing with a lysosome, releasing acid hydrolases which degrade DNA, RNA, proteins and carbohydrates.

Genomics

The genomes of three Leishmania species (L. major, L. infantum and L. braziliensis) have been sequenced, revealing more than 8300 protein-coding and 900 RNA genes. Almost 40% of protein-coding genes fall into 662 families containing between two and 500 members. Most of the smaller gene families are tandem arrays of one to three genes, while the larger gene families are often dispersed in tandem arrays at different loci throughout the genome. Each of the 35 or 36 chromosomes are organized into a small number of gene clusters of tens-to-hundreds of genes on the same DNA strand. These clusters can be organized in head-to-head (divergent) or tail-to-tail (convergent) fashion, with the latter often separated by tRNA, rRNA and/or snRNA genes. Transcription of protein-coding genes initiates bi-directionally in the divergent strand-switch regions between gene clusters and extends polycistronically through each gene cluster before terminating in the strand-switch region separating convergent clusters. Leishmania telomeres are usually relatively small, consisting of a few different types of repeat sequence. Evidence can be found for recombination between several different groups of telomeres. The L. major and L. infantum genomes contain only ~50 copies of inactive degenerated Ingi/L1Tc-related elements (DIREs), while L. braziliensis also contains several telomere-associated transposable elements (TATEs) and spliced leader-associated (SLACs) retroelements. The Leishmania genomes share a conserved core proteome of ~6200 genes with the related trypanosomatids Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma cruzi, but there are ~1000 Leishmania-specific genes (LSGs), which are mostly randomly distributed throughout the genome. There are relatively few (~200) species-specific differences in gene content between the three sequenced Leishmania genomes, but ~8% of the genes appear to be evolving at different rates between the three species, indicative of different selective pressures that could be related to disease pathology. About 65% of protein-coding genes currently lack functional assignment.[2]

Leishmania species produce several different heat shock proteins. These incluse Hsp83, a homolog of Hsp90. A regulatory element in the 3' UTR of Hsp83 controls translation of Hsp83 in a temperature-sensitive manner. This region forms a stable RNA structure which melts at higher temperatures.[23]

Leishmania as component of CVBD (Canine Vector-Borne Diseases)

Other microorganism-based diseases caused by ectoparasites include Bartonella, Borrelia, Babesia, Dirofilaria, Ehrlichia, and Anaplasma.

See also

Literature

- Zandbergen et al. "Leishmania disease development depends on the presence of apoptotic promastigotes in the virulent inoculum", PNAS, Sept. 2006 (PDF)

- Shaw J. J. (1969). The haemoflagellates of sloths. H. K. Lewis & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7186-0318-2 (Full text e-book).

- Myler and Fasel (2008). Leishmania: After The Genome. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-28-8 .

- Ansari MY, Dikhit MR, Sahoo GC, Das P. (2012). "Comparative modeling of HGPRT enzyme of L. donovani and binding affinities of different analogs of GMP". Int J Biol Macromol. 50 (3): 637–49. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.01.010. PMID 22327112.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- ^ a b c Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 749–54. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Myler P; Fasel N (editors). (2008). Leishmania: After The Genome. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-28-8.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "MylerP" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ WHO (2010) Annual report. Geneva

- ^ "Morphology and Life Cycle". UCLA. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Pulvertaft, RJ; Hoyle, GF (1960). "Stages in the life-cycle of Leishmania donovani". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 54 (2): 191–6. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(60)90057-2. PMID 14435316.

- ^ Hughes AL, Piontkivska H. Phylogeny of Trypanosomatidae and Bodonidae (Kinetoplastida) based on 18S rRNA: evidence for paraphyly of Trypanosoma and six other genera. Mol Biol Evol 20(4):644-652

- ^ Momen H, Cupolillo E (2000). "Speculations on the origin and evolution of the genus Leishmania". Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 95 (4): 583–8. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762000000400023. PMID 10904419.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Noyes HA, Morrison DA, Chance ML, Ellis JT (2000). "Evidence for a neotropical origin of Leishmania". Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 95 (4): 575–8. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762000000400021. PMID 10904417.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kerr SF (2000). "Palaearctic origin of Leishmania". Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 95 (1): 75–80. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762000000100011. PMID 10656708.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Kuhls, Katrin (7 June 2011). "Comparative Microsatellite Typing of New World Leishmania infantum Reveals Low Heterogeneity among Populations and Its Recent Old World Origin". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 5 (6): e1155. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001155.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.3201/eid1203.050811, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.3201/eid1203.050811instead. - ^ Noyes HA, Arana BA, Chance ML, Maingon R (1997) The Leishmania hertigi (Kinetoplastida; Trypanosomatidae) complex and the lizard Leishmania: their classification and evidence for a neotropical origin of the Leishmania-Endotrypanum clade. J Eukaryot Microbiol 44(5):511-557

- ^ Croan DG, Morrison DA, Ellis JT (1997) Evolution of the genus Leishmania revealed by comparison of DNA and RNA polymerase gene sequences. Mol Biochem Parasitol 89(2):149-159

- ^ Franco AM, Grimaldi G Jr (1999) Characterization of Endotrypanum (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae), a unique parasite infecting the neotropical tree sloths (Edentata).Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 94(2):261-268

- ^ Momen H, Cupolillo E (2000) Speculations on the origin and evolution of the genus Leishmania. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 95(4):583-588

- ^ Desbois, N.; Pratlong, F.; Quist, D.; Dedet, JP. (2014). "Leishmania (Leishmania) martiniquensis n. sp. (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae), description of the parasite responsible for cutaneous leishmaniasis in Martinique Island (French West Indies)". Parasite. 21: 12. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014011. PMC 3952653. PMID 24626346.

- ^ Leishmania mexicana / Leishmania major

- ^ Visceral leishmniasis: The disease

- ^ kala-azar. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

- ^ Vannier-Santos, MA, (August 2002). "Cell biology of Leishmania spp.: invading and evading". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 8 (4): 297–318. doi:10.2174/1381612023396230. PMID 11860368.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul, William E. (September 1993). "Infectious Diseases and the Immune System". Scientific American: 94–95.

- ^ Laskay T.; et al. (2003). "Neutrophil granulocytes – Trojan horses for Leishmania major and other intracellular microbes?". Trends in Microbiology. 11 (5): 210–4. doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(03)00075-1. PMID 12781523.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ David, M (February 2010). "Preferential translation of Hsp83 in Leishmania requires a thermosensitive polypyrimidine-rich element in the 3' UTR and involves scanning of the 5' UTR". RNA (New York, N.Y.). 16 (2): 364–74. doi:10.1261/rna.1874710. PMC 2811665. PMID 20040590.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- The International Leishmania Network (ILN) has basic information on the disease and links to many aspects of the disease and its vector.

- A discussion list (Leish-L) is also available with over 600 subscribers to the list, ranging from molecular biologists to public health workers, from many countries both inside and outside endemic regions. Comments and questions are welcomed.

- KBD: Kinetoplastid Biology and Disease, is a website devoted to leishmaniasis, sleeping sickness and Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). It contains free access to full text peer-reviewed articles on these subjects. The site contains many articles relating to the unique kinetoplastid organelle and genetic material therein.

- Sexual reproduction in leishmania parasites, short review of a "science"-paper

- World Community Grid: Drug Search for Leishmaniasis