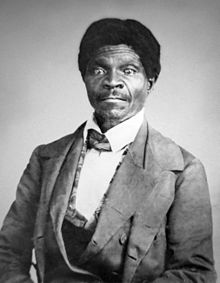

Dred Scott

Dred Scott | |

|---|---|

Dred Scott | |

| Born | Sam Scott circa 1799 Southampton County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | September 17, 1858 (aged c. 59) |

| Nationality | American |

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Dred Scott (circa 1799 – September 17, 1858) was an enslaved African American man in the United States who unsuccessfully sued for his freedom and that of his wife and their two daughters in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case of 1857, popularly known as the "Dred Scott Decision." Scott claimed that he and his wife should be granted freedom because they had lived in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory for four years, where slavery was illegal. The United States Supreme Court decided 7–2 against Scott, finding that neither he nor any other person of African ancestry could claim citizenship in the United States, and therefore Scott could not bring suit in federal court under diversity of citizenship rules. Moreover, Scott's temporary residence outside Missouri did not bring about his emancipation under the Missouri Compromise, which the court ruled unconstitutional as it would improperly deprive Scott's owner of his legal property.

While Chief Justice Roger B. Taney had hoped to settle issues related to slavery and Congressional authority by this decision, it aroused public outrage, deepened sectional tensions between the northern and southern U.S. states, and hastened the eventual explosion of their differences into the American Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and the post-Civil War Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments nullified the decision.

Overview

The case raised the issue of the status of enslaved individuals who had been held captive while residing in a free state. Such states and territories held that a slaveholder forfeited his property rights to his enslaved individuals in a state that prohibited the institution of slavery and where there was no law to support his controlling the slave. Congress had never before addressed whether slaves were free if they set foot upon free soil. The Dred Scott ruling overturned the Missouri Compromise as unconstitutional, holding that slavery was protected in the Constitution, therefore Congress could not regulate it in the federal Territories and deprive a slave owner of his property without due process.

This conclusion enraged the abolitionist Republicans and further exacerbated sectional sentiments that led to the American Civil War. Newspapers at this time covered the case very well, showing people's interest in the topic. Depending on the newspaper (southern or abolitionist) the reporters would either show approval or disapproval towards the decision to deny Scott his freedom.

Scott often traveled with his slave owner Dr. John Emerson, a surgeon in the U.S. Army, who was regularly transferred under Army command. Scott's stay with his slave owner in Illinois, a free state, gave him the legal leverage to make a claim for freedom, as did his extended stay at Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory (now Minnesota), where slavery was also prohibited. Scott did not file a petition for freedom while living in the free lands — perhaps because he was unaware of his rights at the time or perhaps because he was afraid of possible repercussions. After two years, the army transferred Emerson to territory where slavery was legal: first to St. Louis, Missouri, then to Louisiana. After getting married in Louisiana, Emerson commanded the Scotts to return to him.

They could have refused the order by staying in the free territory of Wisconsin (now Minnesota), or by going to the free state of Illinois, but instead they went down the Mississippi River to Louisiana; a voyage of more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km). Emerson died in 1843; his widow directed Scott to work for another officer. At this change Scott sought freedom for his family and himself. He offered $300, about $10,000 in current value, to Emerson's widow, Irene, but she refused to release him. Scott then went to the St. Louis Circuit Court to obtain his freedom.[1]

Life

Circa 1799, Dred Scott was born into slavery in Southampton County, Virginia, as property to the Peter Blow family. From what experts can conclude, Scott was originally named Sam and had an older brother named Dred. However, when the brother died as a young man, Scott chose to take his brother's name instead. The Blow family settled near Huntsville, Alabama, where they unsuccessfully attempted farming in a location that is now occupied by Oakwood University, an HBCU affiliated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church.[2][3][4]

In 1830 the Blow family took Scott with them when they relocated to St. Louis, Missouri.[5] They sold him to John Emerson, a doctor serving in the United States Army.

Marriage and family

In 1836 Dred Scott met a teenaged slave named Harriet Robinson whose slave owner was Major Lawrence Taliaferro, an army officer from Virginia. Taliaferro allowed Scott and Harriet to marry and transferred his ownership of Harriet to Dr. Emerson so the couple could be together. In 1838, Harriet gave birth to their first child, Eliza. In 1840, they had another daughter they named Lizzie. Eventually, they would also have two sons, but neither survived past infancy.[6]

In February 1838, Dr. Emerson married Eliza Irene Sanford in Louisiana,[7] and the Emersons and Scotts returned to Missouri in 1840. In 1842, Emerson left the Army. After he died in the Iowa Territory in 1843, his widow Eliza inherited his estate, including the Scotts. For three years after Emerson's death, she continued to lease out the Scotts as hired slaves. In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase his and his family's freedom, but Eliza Irene Emerson refused, prompting Scott to resort to legal recourse.[8]

Dred Scott case

Having failed to purchase his freedom, in 1846 Scott filed legal suit in St Louis Circuit Court through the help of a local lawyer. Historical details about why Scott sought recourse in the court system are unclear. The Scott v. Emerson case was tried in 1847 in the federal-state courthouse in St. Louis. The judgment went against Scott, but having found evidence of hearsay, the judge called for a retrial.

In 1850, a Missouri jury concluded that Scott and his wife should be granted freedom since they had been illegally held as slaves during their extended residence in the free jurisdictions of Illinois and Wisconsin. Irene Emerson appealed. In 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court struck down the lower court ruling, saying, "Times now are not as they were when the previous decisions on this subject were made."[9] They ruled that the precedent of "once free always free" was no longer the case, overturning 28 years of legal precedent. They told the Scotts they should have sued for freedom in Wisconsin. Justice Hamilton R. Gamble, who was later appointed governor of the state, sharply disagreed with the majority decision and wrote a dissenting opinion. The Scotts were returned to their slave owner's wife.

Under Missouri law at the time, after Dr. Emerson had died, powers of the Emerson estate were transferred to his wife's brother, John F. A. Sanford. Because Sanford was a citizen of New York, Scott's lawyers "claimed the case should now be brought before the Federal courts, on the grounds of diverse citizenship."[10] With the assistance of new lawyers (including Montgomery Blair), the Scotts filed suit in the federal court.

After losing again in federal district court, they appealed to the United States Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford. (The name is spelled "Sandford" in the court decision due to a clerical error.)

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the majority opinion. Taney ruled that:

- Any person descended from Africans, whether slave or free, is not a citizen of the United States, according to the Constitution.

- The Ordinance of 1787 could not confer either freedom or citizenship within the Northwest Territory to non-white individuals.

- The provisions of the Act of 1820, known as the Missouri Compromise, were voided as a legislative act, since the act exceeded the powers of Congress, insofar as it attempted to exclude slavery and impart freedom and citizenship to non-white persons in the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase.[11]

The Court had ruled that African Americans had no claim to freedom or citizenship. Since they were not citizens, they did not possess the legal standing to bring suit in a federal court. As slaves were private property, Congress did not have the power to regulate slavery in the territories and could not revoke a slave owner's rights based on where he lived. This decision nullified the essence of the Missouri Compromise, which divided territories into jurisdictions either free or slave. Speaking for the majority, Taney ruled that because Scott was simply considered the private property of his owners, that he was subject to the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, prohibiting the taking of property from its owner "without due process".

The Scott decision increased tensions between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in both North and South, further pushing the country towards the brink of civil war. Ultimately, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution settled the issue of Black citizenship via Section 1 of that Amendment: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside..."

Post-case freedom

Following the ruling, Scott and his family were returned to Emerson's widow. In the meantime, her brother John Sanford had been committed to an insane asylum.

In 1850, Irene Sanford Emerson had remarried. Her new husband, Calvin C. Chaffee, was an abolitionist, who shortly after their marriage was elected to the U.S. Congress. Chaffee was apparently unaware that his wife owned the most prominent slave in the United States until one month before the Supreme Court decision. By then it was too late for him to intervene. Chaffee was harshly criticized for having been married to a slaveholder. He persuaded Irene to return Scott to the Blow family, his original owners. By this time, the Blow family had relocated to Missouri and become opponents of slavery. Henry Taylor Blow manumitted the four Scotts on May 26, 1857, less than three months after the Supreme Court ruling.

Later life and death

Scott went to work as a porter in St. Louis. His freedom was short-lived. About 17 months later, he died from tuberculosis in September 1858.[12] Scott was survived by his wife and his two daughters.

Burials

Scott was originally interred in Wesleyan Cemetery in St. Louis. When this cemetery was closed nine years later, Taylor Blow transferred Scott's coffin to an unmarked plot in the nearby Catholic Calvary Cemetery, St. Louis, which permitted burial of non-Catholic slaves by Catholic owners.[13] A local tradition later developed of placing Lincoln pennies on top of Scott's gravestone for good luck.[13]

Harriet Scott was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Hillsdale, Missouri. She outlived her husband by 18 years, dying on June 17, 1876.[14]

Aftermath

- The Dred Scott Case ended the prohibition of slavery in federal territories and prohibited Congress from regulating slavery anywhere, overturning the Missouri compromise, enabling "popular sovereignty", and bloody Kansas.[15]

- The ruling of the court helped catalyze sentiment for Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and the three constitutional amendments ratified shortly after the Civil War: the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments, abolishing slavery, granting former slaves citizenship, and conferring citizenship to anyone born in the United States (excluding those subject to a foreign power such as children of foreign ambassadors).[15]

Legacy

- Their daughter Eliza Scott married and had two sons. Lizzie never married but, following her sister's early death, she helped raise her nephews. One of Eliza's sons died young, but the other married and has descendants, some of whom still live in St. Louis as of 2010.[16]

- 1957, Scott's gravesite was rediscovered and flowers were put on it in a ceremony to mark the centennial of the case.[17]

- 1977, the Scotts' great-grandson, John A. Madison, Jr., an attorney, gave the invocation at the ceremony at the Old Courthouse (St. Louis, Missouri) for the dedication of a National Historic Marker commemorating the Scotts' case.[17]

- In 1997, Dred and Harriet Scott were inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[18]

- 1999, a cenotaph was installed for Harriet Scott at her husband's grave to commemorate her role in seeking freedom for them and their children.[17]

- 2001, Harriet and Dred Scott's petition papers were displayed at the main branch of the St. Louis Public Library, following discovery of more than 300 freedom suits in the archives of the circuit court.[17]

- 2006, Harriet Scott's gravesite was proved to be in Hillsdale, Missouri and a biography of her was published in 2009.[17]

- 2006, a new historic plaque was erected at the Old Courthouse to honor the roles of both Dred and Harriet Scott in their freedom suit and its significance in U.S. history.[17]

- 2012, Scott was inducted into the Hall of Famous Missourians; a bronze bust by Missouri sculptor, E. Spencer Schubert will be displayed in the Missouri State Capitol Building.

In popular culture

- Shelia P. Moses and Bonnie Christensen, I, Dred Scott: A Fictional Slave Narrative Based on the Life and Legal Precedent of Dred Scott (2005)[17]

- Mary E. Neighbour, Speak Right On: Dred Scott: A Novel (2006)[17]

- Gregory J. Wallance, Two Men Before the Storm: Arba Crane's Recollection of Dred Scott and the Supreme Court Case That Started the Civil War (2006), novel[17]

See also

Bibliography

- Swain, Gwenyth (2004). Dred and Harriet Scott: A Family's Struggle for Freedom. Saint Paul, MN: Borealis Books. ISBN 978-0-87351-483-5.

- Shurtleff, Mark (2009). Am I Not A Man? The Dred Scott Story. Orem, UT: Valor Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-935546-00-9.

- Tsesis, Alexander (2008). We Shall Overcome: A History of Civil Rights and the Law. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11837-7.

References

- ^ "Dred Scott's fight for freedom: 1846–1857". Africans in America: People & Events. PBS. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ http://www.deepfriedkudzu.com/2011/02/dred-scott-and-oakwood-university.html[full citation needed]

- ^ http://blog.al.com/breaking/2011/04/a_catalyst_for_civil_war_after.html[full citation needed]

- ^ http://www.hsvcity.com/gis/historicmarkers/site/marker_069/page.htm[full citation needed]

- ^ Gunderson, Cory (September 1, 2010). The Dred Scott Decision. ABDO. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-61714-341-0.

- ^ Johnson, George D. (January 17, 2011). "Life". Profiles In Hue. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 34–6. ISBN 978-1-4568-5120-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Vishneski, John S. (October 1988). "What the Court Decided in Dred Scott v. Sandford". The American Journal of Legal History. 32 (4): 373–90. JSTOR 845743.

- ^ Fehrenbacher, Don Edward (2001). The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514588-5.[page needed]

- ^ Scott v. Emerson, 15 Mo. 576, 586 (Mo. 1852) Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ Randall, J. G., and David Donald. A House Divided. The Civil War and Reconstruction. 2nd ed. Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1961, pp. 107–114.

- ^ "Decision of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott Case". The New York Daily Times. New York. March 7, 1857. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Axelrod, Alan (2008). Profiles in Folly: History's Worst Decisions and why They Went Wrong. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-1-4027-4768-7.

- ^ a b O'Neil, Time (March 6, 2007). "Dred Scott: Heirs to History" (PDF). St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Dred Scott Case, 1846–1857". Collections. Missouri Digital Heritage. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ a b Paul Finkleman, Dred Scott v. Sandford: A Brief History with Documents, Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, pp. 7–9, Retrieved February 26, 2011

- ^ Dred and Harriet Scott: Their Family Story, St. Louis Today, KWMU-FM, Interview with author Ruth Ann Hager, Feb 4, 2010, accessed Feb 4, 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Arenson, Adam (2014). "Dred Scott versus the Dred Scott Case: The History and Memory of a Signal Moment in American Slavery, 1857–2007". In Konig, David Thomas; Finkelman, Paul; Bracey, Christopher Alan (eds.). The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Ohio University Press. pp. 25–46. ISBN 978-0-8214-4328-6.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

External links

- "St. Louis Circuit Court Records", A collection of images and transcripts of 19th century Circuit Court Cases in St. Louis, particularly freedom suits, including suits brought by Dred and Harriet Scott. A partnership of Washington University and Missouri History Museum, funded by an IMLS grant

- "Freedom Suits", African-American Life in St. Louis, 1804–1865, from the Records of the St. Louis Courts, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, National Park Service

- Revised Dred Scott Case Collection

- Christyn Elley, "Biography of Dred Scott", Missouri State Archives

- Full text of the Dred Scott v. Sandford, Supreme Court decision Findlaw

- Dred Scott v. Sandford and related resources, Library of Congress

- "Dred Scott Chronology", Washington University in St. Louis

- Harriet Scott's grave located, Afrigeneas Forum

- Dred Scott Heritage Foundation

- Mark Shurtleff, "Am I Not A Man? The Dred Scott Story"

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Works by Dred Scott at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Dred Scott at Internet Archive

- 1790s births

- 1858 deaths

- African-American history of Minnesota

- American slaves

- Burials at Calvary Cemetery (St. Louis)

- Deaths from tuberculosis

- Freedom suits in the United States

- Infectious disease deaths in Missouri

- People from St. Louis, Missouri

- People from Southampton County, Virginia

- United States slavery case law