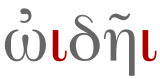

Iota subscript

The iota subscript is a diacritic mark in the Greek alphabet shaped like a small vertical stroke or miniature iota ⟨

The offglide was gradually lost in pronunciation, a process that started already during the classical period and continued during the Hellenistic period, with the result that, from approximately the 1st century BC onwards, the former long diphthongs were no longer distinguished in pronunciation from the simple long vowels (long monophthongs)

During the Roman and Byzantine eras, the iota, now mute, was sometimes still written as a normal letter but was often simply left out. The iota subscript was invented by Byzantine philologists in the 12th century AD as an editorial symbol marking the places where such spelling variation occurred.[2][3][4]

The alternative practice, of writing the mute iota not under, but next to the preceding vowel, is known as iota adscript. In mixed-case environments, it is represented either as a slightly reduced iota (smaller than regular lowercase iota), or as a full-sized lowercase iota. In the latter case, it can be recognized as iota adscript by the fact that it never carries any diacritics (breathing marks, accents).

In uppercase-only environments, it is represented again either as slightly reduced iota (smaller than regular lowercase iota), or as a full-sized uppercase Iota. In digital environments, and for linguistic reasons also in all other environments, the representation as a slightly reduced iota is recommended.[by whom?] There are Unicode codepoints for all Greek uppercase vowels with iota adscript (for example, U+1FBC ᾼ GREEK CAPITAL LETTER ALPHA WITH PROSGEGRAMMENI), allowing for easy implementation of that recommendation in digital environments.

Terminology

[edit]In Greek, the subscript is called ὑπογεγραμμένη (hupogegramménē), the perfect passive participle form of the verb ὑπογράφω (hupográphō), "to write below". Analogously, the adscript is called προσγεγραμμένη (prosgegramménē), from the verb προσγράφω (prosgráphō), "to write next (to something), to add in writing".[5][6]

The Greek names are grammatically feminine participle forms because in medieval Greek the name of the letter iota, to which they implicitly refer, was sometimes construed as a feminine noun (unlike in classical and in modern Greek, where it is neuter).[7] The Greek terms, transliterated according to their modern pronunciation as ypogegrammeni and prosgegrammeni respectively, were also chosen for use in character names in the computer encoding standard Unicode.

As a phonological phenomenon, the original diphthongs denoted by ⟨ᾳ, ῃ, ῳ⟩ are traditionally called "long diphthongs".[8][9] They existed in the Greek language up into the classical period. From the classical period onwards, they changed to simple vowels (monophthongs), but sometimes continued to be written as diphthongs. In the medieval period, these spellings were replaced by spellings with an iota subscript, to mark former diphthongs which were no longer pronounced. In some English works these are referred to as "improper diphthongs".[10][11]

Usage

[edit]

The iota subscript occurs most frequently in certain inflectional affixes of ancient Greek, especially in the dative endings of many nominal forms (e.g.

The rare long diphthong ῡ

The iota subscript is today considered an obligatory feature in the spelling of ancient Greek, but its usage is subject to some variation. In some modern editions of classical texts, the original pronunciation of long diphthongs is represented by the use of iota adscript, with accents and breathing marks placed on the first vowel.[13] The same is generally true for works dealing with epigraphy, paleography or other philological contexts where adherence to original historical spellings and linguistic correctness is considered important.

Different conventions exist for the treatment of subscript/adscript iota with uppercase letters. In Western printing, the most common practice is to use subscript diacritics only in lowercase environments and to use an adscript (i.e. a normal full-sized iota glyph) instead whenever the host letter is capitalized. When this happens in a mixed-case spelling environment (i.e. with only the first letter of a word capitalized, as in proper names and at the beginning of a sentence), then the adscript iota regularly takes the shape of the normal lowercase iota letter (e.g. ᾠ

In modern Greek, subscript iota was generally retained in use in the spelling of the archaizing Katharevousa. It can also be found regularly in older printed Demotic in the 19th and early 20th century, but it is generally absent from the modern spelling of present-day standard Greek. Even when present-day Greek is spelled in the traditional polytonic system, the number of instances where a subscript could be written is much smaller than in older forms of the language, because most of its typical grammatical environments no longer occur: the old dative case is not used in modern Greek except in a few fossilized phrases (e.g. ἐ

Transliteration

[edit]In transliteration of Greek into the Latin alphabet, the iota subscript is often omitted. The Chicago Manual of Style, however, recommends the iota subscript be "transliterated by an i on the line, following the vowel it is associated with (ἀνθρώπῳ, anthrṓpōi)." (11.131 in the 16th edition, 10.131 in the 15th.)

Computer encoding

[edit]In the Unicode standard, iota subscript is represented by a non-spacing combining diacritic character U+0345 "Combining Greek Ypogegrammeni". There is also a spacing clone of this character (U+037A, ͺ), as well as 36 precomposed characters, representing each of the usual combinations of iota subscript with lowercase

In the ASCII-based encoding standard Beta Code, the iota subscript is represented by the pipe character "|" placed after the letter.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Woodard, Roger D. (2008). "Attic Greek". The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-139-46932-6.

- ^ McLean, Bradley H. (2011). New Testament Greek: an introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 20.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce Manning (1981). Manuscripts of the Greek bible: an introduction to Greek palaeography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-502924-6.

- ^ Sihler, Andrew L. (2008). New comparative grammar of Greek and Latin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 59.

- ^ Dickey, Eleanor (2007). Ancient Greek scholarship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 256.

- ^ Babiniotis, Georgios. προσγράφω. Lexiko tis Neas Ellinikis Glossas.

- ^ Babiniotis, Georgios. υπογράφω. Lexiko tis Neas Ellinikis Glossas.

- ^ Mastronarde, Donald J (1993). Introduction to Attic Greek. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 9f.

- ^ Smyth, Herbert W. (1920). Greek grammar for colleges. New York: American Book Company. p. 9.;

- ^ Mounce, William D. (November 28, 2009). Basics of Biblical Greek (3rd ed.). Zondervan. p. 10. ISBN 978-0310287681.

- ^ von Ostermann, George Frederick; Giegengack, Augustus E. (1936). Manual of foreign languages for the use of printers and translators. United States. Government Printing Office. p. 81.

- ^ Eustathius of Thessalonica, Commentary on the Iliad, III 439.

- ^ Ritter, R. M. (2005). New Hart's Rules: The Handbook of Style for Writers and Editors. OUP Oxford. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-19-165049-9.

- ^ a b Nicholas, Nick. "Titlecase and Adscripts". Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ The difference in number between uppercase and lowercase precomposed characters is due to the fact that there are no uppercase combinations with only an accent but no breathing mark, because such combinations do not occur in normal Greek orthography (uppercase letters with accents are used only word-initially, and word-initial vowel letters always have a breathing mark).

- ^ Thesaurus Linguae Graecae. "The beta code manual". Retrieved 5 August 2012.