Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

| Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh | |

|---|---|

| NHS Lothian | |

Main entrance | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Little France, Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 55°55′22″N 3°08′12″W / 55.9229°N 3.1366°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | NHS Scotland |

| Type | Teaching |

| Affiliated university | University of Edinburgh Medical School |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | Yes[1] |

| Beds | >900 |

| Helipad | Yes |

| History | |

| Opened | 1729 |

| Links | |

| Website | Official website |

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (RIE) was established in 1729, and is the oldest voluntary hospital in Scotland. The new buildings of 1879 were claimed to be the largest voluntary hospital in the United Kingdom, and later on, the Empire.[2] The hospital moved to a new 900 bed site in 2003 in Little France. It is the site of clinical medicine teaching as well as a teaching hospital for the University of Edinburgh Medical School. In 1960 the first successful kidney transplant performed in the UK was at this hospital.[3] In 1964 the world's first coronary care unit was established at the hospital.[4] It is the only site for liver, pancreas, and pancreatic islet cell transplantation in Scotland, and one of the country's two sites for kidney transplantation.[5] In 2012, the Emergency Department had 113,000 patient attendances, the highest number in Scotland.[6] It is managed by NHS Lothian.

History

[edit]Foundation and early history

[edit]John Munro, President of the Incorporation of Surgeons in 1712, set in motion a project to establish a "Seminary of Medical Education" in Edinburgh, of which a General Hospital was an integral part.[7] His son, Alexander Monro primus, by then Professor of Anatomy, circulated an anonymous pamphlet in 1721 on the necessity and advantage of erecting a hospital for the sick and poor. In 1725, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh wrote to the stock-holders of the Fishery Company, which was about to be wound up, suggesting that they assign their shares for the purpose of such a hospital. Other donors included many wealthy citizens, most of the physicians and several surgeons, numerous Church of Scotland parishes (at the urging of their Assembly) and the Episcopal meeting houses in Edinburgh.[8]

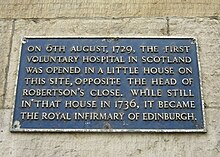

The committee set up by the donors leased "a house of small rent" near the college from the university for 19 years. Known, at first, as the Hospital for the Sick Poor, the Physicians' Hospital, or Little House, it was established on 6 August 1729 at the head of Robertson's Close on the site of the building on the corner of South Bridge and Infirmary Street. It is now marked with a plaque.[9]

A "gentlewoman" was engaged as Mistress or House-keeper, and a "Nurse or Servant" was hired for the patients, both women to be resident and "free of the burden of children and the care of a separate family." The physicians, who had seen the poor gratis twice weekly at their college, arranged for one of their number to attend the hospital, to see both inpatients and outpatients. Six Surgeon-Apothecaries (Alexander Monro, John McGill, Francis Congalton, Robert Hope, John Douglas and George Cunninghame) also agreed to attend in turn, and to dispense the medicines prescribed by the physicians from their own shops, also without payment.[10]

The first patient, a lady from Caithness, was suffering from "chlorosis." She was discharged and recovered after three months. Thirty five patients were admitted in the first year, of whom 19 were cured, 5 recovered, 5 dismissed, either as incurable or for irregularities, and one died in the hospital (of "consumption"). They came from all over Scotland, but mainly from Edinburgh and its environs. Diseases cured included pains, inflammations, agues, ulcers, cancers, palsies, flux, consumption, hysterick disorders and melancholy. A free advice and medicine service for out-patients was very popular, receiving a 1,000 patients by 1754,[11] which presented the hospital with prohibitively high costs and demand. Fundraising began for a new hospital, driven by Monro and Drummond, and the appeal attracted funds from churches throughout Scotland, landed gentry, private individuals, and prominent professionals including physicians, surgeons, merchants and lawyers, as well as donations of labour and building materials.[11]

Infirmary Street

[edit]

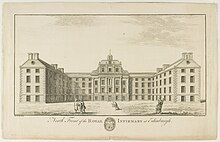

The infirmary received a Royal Charter from George II in 1736 which gave it its name of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh[12] and commissioned William Adam to design a new hospital on a site close by to the original building, on what later became Infirmary Street. In 1741 the hospital moved the short distance to the not yet completed building which eventually, on its completion in 1745, had 228 beds compared to 4 beds in the Little House.[13]

In 1750, Scottish surgeon Archibald Kerr left a slave plantation he owned in Jamaica, Red Hill Pen, to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh in his will. Kerr also left the 39 slaves which were kept as forced labourers on the plantation to the infirmary, which owned Red Hill Pen from 1750 to 1893 (with slavery being abolished in Jamaica in 1833). According to the BBC, the infirmary used the wealth generated from Red Hill Pen to "buy medicines, construct a new building, employ staff, and heal Edinburgh's "sick poor"." In 2023, the health board of NHS Lothian publicly announced that they would be providing reparations for slavery after discovering the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh's ownership of the plantation.[14]

By the 1830s, the hospital had become short of space and, in 1832, the former Royal High School in nearby High School Yards, built by Alexander Laing in 1777, was converted to a surgical hospital with a new operating theatre built to the east. This was soon found to be inadequate and a new surgical hospital, designed by David Bryce, was built fronting Drummond Street, opening in 1853. The new building was linked to the High School Yards building by an extension to the north.[15]

The Infirmary Street buildings were demolished in 1884 and replaced with public swimming baths and a school. The ornamental gates and gate piers now front the former surgical hospital on Drummond Street. The four attached Ionic columns on the frontispiece of the hospital were removed and incorporated as a combined column in a monument to the Covenanters who were defeated at the Battle of Rullion Green. This stands outside the entrance to Dreghorn Barracks on Redford Road in the south west of the city.[16]

The original surgical theatre, which was on the roof of the 1741 building, was re-erected as part of stables in the grounds of Redford House, also on Redford Road. It has since been converted into a house known as Drummond Scrolls taking its name from the large attached carved bracket scrolls, also from the surgical theatre of 1741. The house is category B-listed by Historic Scotland.[17]

The New System

[edit]Significant changes came with the introduction of the "New System" in 1873. Four years before, Sir Joseph Lister had been appointed as Professor of Surgery to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.[18] Using antiseptics and narcotics he proved to be very successful, thus attracting patients from higher social classes to the hospital.[19] The hospital managers felt the existing nurses were lacking both medical knowledge and appropriate behaviour. They appointed Deputy Surgeon-General Charles Hamilton Fasson as Medical Superintendent. Fasson recruited a group of 17 trained Nightingale Nurses from St. Thomas’s Hospital London. In 1873 Elizabeth Barclay and Angélique Lucille Pringle started building up a system of nursing where the nurses were under the control of the Lady Superintendent of Nurses instead of individual ward doctors. They also introduced a systematic training of nurses, who were, after one year of probation, admitted to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh’s Register Book. Accordingly, the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh had implemented the first Scottish nursing school. Up to the movement into the new buildings 102 probationers had been entered into the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh’s Registry Book.[20]

Lauriston Place

[edit]

In 1871 a new Superintendent, Charles Hamilton Fasson, was placed in overall charge of the Drummond Street infirmary but felt a new hospital was required on modern standards, and convinced Edinburgh Town council to underwrite the cost of a new infirmary on Lauriston Place. He oversaw the design and construction and remained Superintendent of the new infirmary until his death in 1892.[21]

In 1879, at the instruction of the then Lord Provost, Thomas Jamieson Boyd,[22] the infirmary moved to a new location, then in the fresher air of the edge of the city.[23] The site, on Lauriston Place, had been occupied by George Watson's Hospital (a school, known then as a hospital). The school moved a short distance away to the former Merchant Maiden Hospital (another school) in Archibald Place. The original school building, by the same William Adam as the earlier infirmary, was incorporated into the new David Bryce-designed infirmary buildings and the chapel remained in use for the entirety of the infirmary's occupation of the site.[24]

In the 1920s, the hospital needed to expand, and once again George Watson's College was asked to move. An arrangement was reached to acquire the school's site, with the school to remain there until new premises could be built elsewhere. By 1932, the school's new premises in Colinton Road were ready, and the old Archibald Place building was demolished to make way for the Simpson Memorial Pavilion, used primarily as a maternity wing.[25] In 1948, the infirmary was incorporated into the National Health Service (NHS).[26] The liver transplant unit opened in 1992.[27]

In May 2001, Lothian Health Trust sold the 20-acre (81,000 m2) Lauriston Place site for £30 million to Southside Capital Ltd., a consortium comprising Taylor Woodrow, Kilmartin Property Group, and the Bank of Scotland. It has been redeveloped as the Quartermile housing, shopping, leisure and hotel development. Much of the David Bryce infirmary will remain visible, but some infirmary buildings have been demolished. In the build-up to the move to Little France, the Royal Charter awarded by George II in 1736 was rediscovered.[28]

Little France

[edit]A new hospital sited on a mostly green field site at Little France in the south-east of the city, was procured under a Private Finance Initiative contract in 1998. The new location reflected the need for the hospital to serve not just people living in Edinburgh, but also Midlothian and East Lothian. The new hospital is physically linked to the Chancellor's Building which is the main teaching facility for the University of Edinburgh's Medical School.[29] The new building which was designed by Keppie Design and constructed by Balfour Beatty[30] at a cost of £184 million[31] opened in 2003.[32] The building was built without air conditioning, meaning that portable units are required for the summer months.[33]

The Little France site initially attracted some controversy in the local media such as the Edinburgh Evening News, not least because the city's main accident and emergency facilities are some distance from the city centre, but also because the public transport links to the site had been criticised as inadequate.[34] Furthermore, the economic consultants Jim and Margaret Cuthbert unveiled evidence in the Scottish Left Review outlining why the PFI scheme was a poor use of public funds whilst resulting in huge profits for private investors.[35]

In 2012, the hospital began TAVI procedures for the first time in Scotland.[36] On 16 November 2014, the University announced the Royal Infirmary as the location of Scotland's first PET-MRI Scanner.[37]

In 2016, the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh became one of four major trauma centres where specialist services are based as part of a new national major trauma network in Scotland.[38] In 2021, the Royal Hospital for Children and Young People opened on the Little France site adjacent to the Infirmary, this being a replacement for the former Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Sciennes.[39]

In 2020, the hospital saw the Department for Clinical Neurosciences move to the Little France site having previously been based at Western General Hospital; senior doctors condemned the move in the middle of the COVID-19 crisis as "incomprehensible".[40]

Achievements

[edit]- 1960 - First kidney transplant in the UK by Sir Michael Woodruff[3]

- 1964 - World's first Coronary Care Unit established by Desmond Julian[4]

- 2000 - Scotland's first combined kidney and pancreas transplant [41]

- 2008 - Scotland's first live donor liver transplant by Murat Akyol and Ernest Hidalgo [42]

- 2011 - Scotland's first pancreatic islet cell transplantation [43]

- 2012 - Scotland's first transcatheter aortic valve replacement performed by Neal Uren[44]

The Infirmary in literature

[edit]The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh has often been described in works of fiction, biography and history, and depicted from both the point of view of the sick and those caring for them. The English poet William Ernest Henley e.g. stayed as a patient at the RIE for three years (1873–75). In several poems he portrayed hospital life as well as individual nurses.[45][46]

Nursing history at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

[edit]The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh referred to ‘matrons’ as ‘Mistresses’, starting from 1729 when it was based at ‘The Little House’. The role was more akin to a housekeeper but she did administer medicines. She was assisted by a number of ‘servants’ but very unwell patients were looked after by medical students. The term ‘Mistress’ was replaced with Superintendent of Nurses from 1866 to 1871 then Lady Superintendent of Nurses from 1872.[47] The Preliminary Training School for Nurses was introduced in 1924.[48]

Lady Superintendent of Nurses

[edit]The following were lady superintendents of nurses:[47]

- Miss Elizabeth Anne Barclay 1872 – 1874. During her time the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh’s School of Nursing was founded in 1872. Miss Barclay trained as a Nightingale nurse and had worked at hospitals in Germany. She arrived at the Royal with Miss Pringle and a group of Nightingale nurses.[49]

- Miss Angelique Lucille Pringle 1874 – 1887. When she left in 1887 she took up the position of Matron of St Thomas’s and Superintendent of the Nightingale School.[50]

- Miss Frances Elizabeth Spencer 1887 – 1907. Miss Spencer organised awards and prizes and arranged for tutorials to be delivered by the assistant Lady Superintendent.[51]

- Miss Annie Warren Gill CBE, RRC & Bar 1907 – 1925 [52]

- Miss Ellen Frances Bladdon 1925 – 1931

- Miss Elizabeth Dunlop Smaill OBE[53] 1931 – 1944. Miss Smaill previously worked in Bulgaria in the Balkans war and in France in the first World War.[54]

- Miss Margaret Colville Marshall 1944 – 1955. Miss Marshall had previously held the position of Chief Nursing Officer in the Scottish Department of Health. This was the time of the transition into the NHS.

- Miss Ida Barbara Helen Quaile (nee Renton), OBE 1955 – 1959 [55][56]

- Miss Mary Hutcheson Cordiner 1959 – 1967

- Miss Muriel Florence Cullen 1967 until her appointment as Chief Nursing Officer in 1972.[57]

Other prominent nurses

[edit]- Alice Fisher (1839 – 1888) pioneer in nurse education and author of Hints for Hospital Nurses [58]

Famous patients

[edit]- Former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown had experimental eye surgery performed as a young undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh to save his right eye after suffering from retinal detachment after a rugby union accident.[59]

- Clarissa Dickson Wright, cookery presenter and one half of the Two Fat Ladies duo died on 15 March 2014 from pneumonia.

- Leader of the Scottish Conservatives, Ruth Davidson gave birth to a baby boy on 26 October 2018; she and her partner, Jen, named their son Finn.[60]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Edinburgh & Lothians Emergency Medicine Website". Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "In Coming Days" The Edinburgh Royal Infirmary Souvenir Brochure 1942

- ^ a b "History of Kidney Transplantation". www.edren.org. University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ a b "World's first coronary care unit". British Heart Foundation. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Transplant Units". NHS Blood and Transplant. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh: Emergency Department". Edinburgh Emergency Medicine. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ John Smith, The Origin, Progress and Present Position of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh 1505-1905. Edinburgh: 1905

- ^ An Account of the Rise and Establishment of the Infirmary, or HOSPITAL for SICK-POOR, erected at Edinburgh. 1730. Reprinted prob. 1980

- ^ Comrie, J.D. (1932). History of Scottish Medicine to 1860 (PDF). Wellcome Historical Medical Museum. p. 125.

- ^ Grants Old and New Edinburgh

- ^ a b Blackden, Stephanie (1981). A Tradition of Excellence: A Brief History of Medicine in Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Duncan, Flockhart & Co. Ltd. p. 9.

- ^ "Royal Charter of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh". Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh History". NHS Lothian. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ "NHS Lothian to make amends for slave ownership in 18th Century". 5 October 2023 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, High School Yards, Royal High School Of Edinburgh (118777)". Canmore. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "Monumental Folly – the "Covenanters' Monument"". Word Press. 11 October 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, 141 Redford Road, Redford House, Drummond Scrolls (144619)". Canmore. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Goldmann M (1987) Lister ward. Bristol: Adam Hilger

- ^ Wrench G T (1913) Lord Lister. His Life and Work. London: Fisher Unwin

- ^ Schmidt-Richter R; A review of the introduction of systematic training for nurses at the Royal Infirmary Edinburgh 1872 - 1879. Edinburgh, Univ., Master of science in nursing and health studies, 1993

- ^ The Hospital (periodical) 17 December 1892

- ^ "Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002" (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "1 Lauriston Place, Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, Main Block, including linked original ward pavilions (LB30306)". Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, Lauriston Place, Royal Infirmary, Chapel (207116)". Canmore. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ LHSA. "Edinburgh Royal Maternity Hospital and Simpson Memorial Maternity Pavilion collection summary". lhsa.lib.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "Scotland in 1948". 60 years of NHS Scotland. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "History of the Liver Unit". NHS Lothian. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "It's Get Charter". Edinburgh Evening News. 3 October 2003. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "Little France". University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ "PFI hospital opens its doors". BBC. 28 January 2002. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ "New Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, Keppie Architects, Edinburgh Royal Infirmary". Edinburgh Architecture. 27 September 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ "Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (RIE)". NHS Lothian. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ "NHS staff threaten action on overheating hospital". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 30 July 2006.

- ^ "Outcry over rise in Edinburgh Royal Infirmary parking fees". Edinburgh Evening News. 23 March 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Administrator. "Scottish Left Review - Lifting the Lid on PFI". scottishleftreview.org. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ Walker, Natalie (11 September 2012). "Edinburgh Royal Infirmary first in Scotland to offer new heart procedure". The Scotsman. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "New high-tech scanner to aid university's dementia research". STV. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Scotland trauma centres network 'to boost emergency care'". BBC News. 27 April 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "Edinburgh Sick Kids: The unusable hospital that is finally open". BBC. 23 March 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "Senior doctors condemn 'incomprehensible' decision to move to new hospital during Covid-19 outbreak". Evening News. 26 March 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Renal Transplant Unit Home Page". University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "Surgeons behind Scotland's first live liver transplant tell of 15 hour operation". The Scotsman. 28 February 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Islet Cell Programme". NHS Scotland. Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "Scots patients losing out on new heart surgery". The Scotsman. 11 September 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Henley W E (1875): Hospital Outlines: Sketches and Portraits. Cornhill Magazine Vol XXXII pp 120 - 128

- ^ Henley W E (1921): Poems. London: Macmillan

- ^ a b "Mistresses of the Royal Infirmary". Nursing Times. 68 (40). 1972.

- ^ Logan Turner, A (1979). Story of a Great Hospital. The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh 1729-1929. The Mercat Press.

- ^ "Women and the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, 1870-1950". www.lhsa.lib.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Death of a Pioneer Nurse". Nursing Times. 16 (776): 300. 1920.

- ^ "Mistresses of the Royal Infirmary". Nursing Times. 68 (40). 1972.

- ^ "A Great Loss to the Profession". Nursing Times. 26 (1297): 281. 1930.

- ^ Logan Turner, A (1979). Story of a great Hospital. The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh 1729-1929. The Mercat Press.

- ^ "Mistresses of the Royal Infirmary". Nursing Times. 68 (40). 1972.

- ^ Ewan, Elizabeth; Innes, Sue; Reynolds, Siân; Pipes, Rose, eds. (2006). Quaile, Barbara at The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 294. ISBN 9780748632930.

- ^ "Barbara Quaile". The Herald. 2 March 1999. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Mistresses of the Royal Infirmary". Nursing Times. 68 (40). 1972.

- ^ Williams, R; Fisher, Alice (1877). Hints for Hospital Nurse. Edinburgh: Maclachlan & Stewart.

- ^ Gaby Hinsliff (10 October 2009). "How Gordon Brown's loss of an eye informs his view of the world". The Observer. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013.

- ^ "Ruth Davidson gives birth to baby boy". BBC. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

External links

[edit]- Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

- 1729 establishments in Scotland

- NHS Scotland hospitals

- Buildings and structures completed in 1741

- Hospital buildings completed in the 18th century

- Hospital buildings completed in 1853

- Hospitals in Edinburgh

- Organisations based in Edinburgh with royal patronage

- Hospitals established in the 1720s

- University of Edinburgh

- NHS Lothian

- Voluntary hospitals