Gay Head Light

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

| |

| |

| Location | Aquinnah, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°20′54.4″N 70°50′5.8″W / 41.348444°N 70.834944°W |

| Tower | |

| Constructed | 1799 |

| Foundation | Granite stone on cement |

| Construction | Brick and sandstone |

| Automated | 1960 |

| Height | 15.5 m (51 ft) |

| Shape | Conical |

| Markings | Red brick with black lantern |

| Heritage | National Register of Historic Places listed place, America's Most Endangered Places |

| Fog signal | none |

| Light | |

| First lit | 1856 (current structure) |

| Focal height | 170 feet (52 m) |

| Lens | First order Fresnel lens (original), DCB-224 (current) |

| Range | White 24 nautical miles (44 km; 28 mi) Red 20 nautical miles (37 km; 23 mi) |

| Characteristic | |

Gay Head Light | |

| Location | Lighthouse Rd., Aquinnah, Massachusetts |

| Area | 2 acres (1ha) |

| Built | 1856 |

| MPS | Lighthouses of Massachusetts TR |

| NRHP reference No. | 87001464[1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 15, 1987 |

Gay Head Light is a historic lighthouse located on Martha's Vineyard westernmost point off of Lighthouse Road in Aquinnah, Massachusetts.[2][3]

History

[edit]1796–1838 – Gay Head Light – the first lighthouse on Martha's Vineyard

[edit]When the first Congress of the newly formed United States government met in 1789, one of its first acts was to assume responsibility for lighthouses and other aids to navigation along the country's coastline. For the next twenty-five years, design and construction of new lighthouses were authorized by Congress. The location, size, design, and construction of each lighthouse was considered of such vital importance, that the decision-making process involved the highest officials, including the President.

In 1796, Massachusetts State Senator, Peleg Coffin, requested a lighthouse be installed on Martha's Vineyard above the Gay Head cliffs overlooking a dangerous section of underwater rocks known as "Devil's Bridge." Senator Peleg's request to his Congressman in Washington was substantiated by the maritime traffic navigating the waters between Gay Head and the Elizabeth Islands, which would eventually be reported in a late 1800s Massachusetts study at 80,000 vessels annually. As the state representative for Nantucket, Peleg Coffin also had the whaling industry interests of Nantucket in mind. The Gay Head lighthouse was authorized in 1798 by the United States Congress during the presidency of John Adams. This authorization was to help facilitate safe passage for vessels passing through the hazardous Vineyard Sound waters near the Gay Head cliffs.

In 1799, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts deeded two acres and four rods to the Federal Government for the purpose of building a lighthouse overlooking the clay cliffs and Devil's Bridge. During the same year, President John Adams approved a contract with Martin Lincoln of Hingham, Massachusetts, to build a 47-foot octagonal wooden lighthouse tower on a stone base (including light room); a 17 x 26-foot wooden keeper's house; a whale oil storage building, and various other outbuildings. This wooden octagonal lighthouse is illustrated in the ca. 1800 woodcut shown below left. Charles Edward Banks, who published "The history of Martha's Vineyard" in 1911 wrote, "This wooden tower lasted sixty years, and the site of it, nearer the brow of the cliffs than the present one, can be seen yet in a circular elevation of the soil.

The planned 1799 installation of a Gay Head lighthouse, along with a full-time lighthouse Superintendent and his family, represented the first "Whiteman" homestead established in Gay Head. During the planning process of designing and building the first Gay Head lighthouse in 1799, there was some concern expressed about the impact of a Whiteman settlement in Gay Head. William Rotch, a supplier of whale oil, wrote a letter to Congress on September 28, 1799. Rotch's letter recommended that Captain Owen Hillman, of Martha's Vineyard, be appointed lighthouse Keeper. Most of the letter, however, discussed the subject of how a certain aspect of Whiteman's culture may negatively impact the indigenous Wampanoag community. A section of Rotch's letter states: "As this light house is in a neighborhood of peaceful natives who are industrious and temperate, it is the fear of some of the most considerate that the Superintendent [Keeper of the lighthouse] may injure them by selling them liquor and, feeling much concern for that people, we hope it will meet thy views to have him put under positive restrictions thereupon."[4]

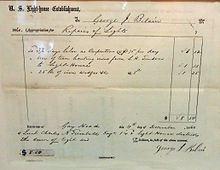

In the fall of 1799, Congress chose not to appoint Owen Hillman as Keeper. Instead, Congress chose Ebenezer Skiff as the island's first Principal Keeper. Skiff became the first white man of European descent to live in the town of Gay Head. On 18 November 1799, Ebenezer Skiff ignited the spider lamp inside the tower's lighting room, officially illuminating the Gay Head Light for the first time as an aide to navigation. The light was projected from lamp wicks fueled by sperm whale oil.[5] Spider lamps were the principal source of light in U.S. lighthouses in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. They consisted of a pan of oil with a wick system that was first used in Boston Light in 1790. Spider lamps were known to produce fumes that burned the Keeper's eyes and obscured the light's glass with an oily smudge. The first Gay Head Light "...was a white flash, was produced by fourteen lamps burning sperm oil, and it is part of tradition of the place that there was quite as much smoke as flame resulting from the combustion of this illuminant. The Keeper was often obliged to wear a veil while in the tower, and the cleansing of the smudge on the glass lantern was no small part of his job." Gay Head Light was one of several early U. S. lighthouses to use a so-called "revolving illuminating apparatus" to generate a flashing white light signal. The revolving illuminating apparatus consisted of sperm whale oil lamps placed on circular service tables attached to a Pedestal rotated by wooden clockwork. According to complaint by the light's first Keeper, Ebenezer Skiff, during cold or damp weather, the wooden clockwork became swollen, which required that the Keeper turn the rotating lighting mechanism by hand. At times, Keeper Skiff hired local Aquinnah Indians at $1.00 per day to help maintain and rotate the Light. Ebenezer Skiff also became involved with teaching Gay Head Wampanoag children.

Ebenezer Skiff's original salary as Principal Keeper in 1799 was $200 per year. After a few years as Keeper of the Gay Head Light, Ebenezer Skiff realized that the job of keeping the sperm-oil-fired light was more arduous and time-consuming than anticipated. It also took many hours of labor to keep the glass surrounding the light clean of the smudge produced by the fumes. There was also the challenge of keeping the lantern glass clean of airborne deposits of clay particles from the nearby clay cliffs. After a few years of service, Ebenezer Skiff gathered the courage to write a letter requesting a pay increase to Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury. Gayhead, October 25, 1805. Keeper Skiff's letter read as follows:

"Sir: Clay and Oker of different colours from which this place derived its name ascend in a Sheet of wind from the high Clifts and catch on the light House Glass, which often requires cleaning on the outside – tedious service in cold weather, and additional to what is necessary in any other part of the Massachusetts. The spring of water in the edge of the Clift is not sufficient. I have carted almost the whole of the water used in my family during the last Summer and until this Month commenced, from nearly one mile distant. These impediments were neither known nor under Consideration at the time of fixing my Salary. I humbly pray you to think of me, and (if it shall be consistent with your wisdom) increase my Salary. And in duty bound I am yours to Command. EBENEZER SKIFF Keeper of Gayhead Light House"

Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, reviewed Ebenezer's letter and saw the merit of Keeper Skiff's request for a pay increase. In the fall of 1805, President Thomas Jefferson increased Keeper Skiff's annual salary by $50 from $200 to $250. Skiff served as the Gay Head Light Principal Keeper for twenty-nine years (1799–1828). Between 1805 and 1828, Ebenezer Skiff received one additional $50 raise. Sometime between the years of 1810–12, Keeper Ebenezer Skiff oversaw the replacement of the original spider lighthouse optics by ten new Lewis Patent Lamps. During the testing phase of the Lewis Patent Lamps – they allegedly proved to burn brighter while using about half the oil required by spider lamps. The statement that Lewis-Patent lamps were an improvement over the Spider Lamps was questioned by mariners.

In 1820, the spring at the Gay Head Light went dry, requiring Skiff to submit a request for a cart and casks to use in fetching water from a distant spring. Stephen Pleasonton, Fifth Auditor at the Treasury, asked Skiff to provide a budget for the cart and casks. Upon receipt of the cost, Pleasonton authorized Ebenezer Skiff “...to procure a pair of wheels and water casks for the use of the Keeper of Gayhead Light House, provided the expense shall not exceed the sum you state, viz., fifty dollars.”[6] In 1828, Ebenezer Skiff's son, Ellis Skiff, assumed the position of Principal Keeper at the Gay Head Light. Keeper Ellis Skiff's beginning annual salary in 1828 was $350, which at the time, was considered a relatively good annual income compared to other United States lighthouse keepers. Ellis Skiff served as the Principal Gay Head Lighthouse Keeper for seventeen years from 1828 to 1845.

1838–1854

[edit]Circa 1838, a new 10 parabolic lens was installed. At the same time, the lantern was lowered 14 feet (4 m) to get the light under the fog. It was also in 1838 that Lt. Edward W. Carpenter did a structural inspection of the Gay Head Light. He noted that the light made one complete revolution every four minutes; that the light and premises were in good order, and that the light was visible for more than twenty miles. In 1838, the lighting room was lowered again the same year by 3 feet (1 m) during a major rebuilding of the lantern and deck by a New Bedford blacksmith. Another significant improvement between 1799 and 1838 was the installation of a Benjamin Franklin pointed tip lightning rod on top of the lighthouse. Benjamin Franklin appreciated the value of lighthouses to society and is quoted as saying, "Lighthouses are more helpful than churches." Lightning strikes to the Gay Head Light are physically documented by the cracked cast iron lightning rod ball displayed on the grounds of today's Martha's Vineyard Museum. The changes to the Gay Head Light; its buildings and grounds, and the presence of the lightning rod are clearly illustrated in the 1839 woodcut print shown lower right.

Harmful lightning strikes to America's early lighthouses were not uncommon. Considering that the tall lighthouses were usually the only structures of any height for several miles, it made them susceptible to multiple lightning strikes storm after storm. In June 1766, the New York Mercury reported: "The 26th Instant, the Lighthouse at Sandy Hook was struck by Lightning, and twenty panes of the Glass Lanthorn broke to pieces; the chimney and Porch belonging to the kitchen was broken down, and some people that were in the House received a little Hurt, but are since recovered. ‘Tis said the Gust was attended with a heavy shower of Hail." The Sandy Hook Lighthouse was built in 1764, was octagonal in shape, and was made of local rubble stone.

In 1842, the octagonal wooden lighthouse constructed in 1799 at Gay Head was reported by the civil engineer, I.W.P. Lewis, as being "decayed in several places," and that both the lighthouse and its nearby Keeper's house needed replacement. In his capacity as a civil engineer, Lewis submitted reports on several lighthouses along the Northeast Coast, including Brown's Head Light; Portland Head Lighthouse; Owls Head Lighthouse and others. Lewis' wrote his noteworthy report about the Gay Head Lighthouse after also inspecting the Cape Pogue, Tarpaulin Cove lighthouses. All three wooden lights "...were found in a state of partial or complete ruin and all require rebuilding."[1] Lewis wrote his report about the Gay Head Light after visiting it in the fall of 1842. In his report, Lewis wrote that the Gay Head Keeper's house was "shaken like a reed" during storms. However, in spite of Lewis' negative report, replacement of the Gay Head Light and Keeper's dwelling was postponed. In 1844, the octagonal wooden light tower was moved back 75 feet from the eroding clay cliffs by John Mayhew of Edgartown at a cost of $386.87.[5] When Lewis was traveling and inspecting lighthouses in 1842, America had 246 lighthouses and 30 lightships.

The early 1850s was a time of transition from the old lighthouse oversight regime under Auditor Stephen Pleasonton, to the new Congressional appointed Light House Board. During this transition phase, there were two simultaneous agendas to improve the light at Gay Head. One agenda was by the long-reigning (30 years) and outgoing head of the lighthouse oversight service, Stephen Pleasonton. The other agenda was by the new, Congressional appointed, Light House Board. In 1852 America had a total of 332 lighthouses and 42 lightships.[7] It was in 1852 that Congress transferred oversight of the nation's lighthouses from Pleasonton to the professional Light House Board. However, in 1852, due to previous efforts undertaken during Pleasonton's reign – the Congressional Light House appropriation bill approved $13,000 to refit and improve the existing 1799 wooden Gay Head Light. With the $13,000 already approved for improvements at the old wooden Gay Head Light, the newly appointed Light House Board found itself fulfilling Pleasonton's agenda for improvements in 1854. On May 26, 1854, the Gazette of Martha's Vineyard reported: "We learn that the Light House Board are about to remove the old lantern and lighting apparatus from Gay Head Light and to erect thereon a new lantern glazed with large-size plate glass. In this is to be placed 13 new lamps with the largest sized reflectors...The business of lighting our sea coast is in the hands of an active and efficient board of officers and great improvements are now being made..." By July, 1854, the $13,000 was spent and the new lantern apparatus installed in the wooden lighthouse tower. In July, 1854, the Gazette reported, "The old lantern...has been replaced by a new one which revolves in about 3 minutes and 58 seconds, with an interval between each flash of 1 minute 59 seconds. The new Light is of much greater power."[8] In 1854 the newly established U.S. Lighthouse Board moved forward with their plan to replace the "renovated and improved" wooden tower with a redbrick tower supporting a First-Order Fresnel Lens.

1854–1874

[edit]

Even though the newly installed 1854 light was of "greater power," the 1854 apparatus was considered inferior to the newly developed Fresnel technology. At the same time, the wooden lighthouse tower was judged to be in questionable condition, and the light's position was considered threatened by the eroding clay cliffs. In 1852, the Federal Lighthouse Board issued a 760-page report stating that Gay Head Lighthouse was “not second to any on the eastern coast, and should be fitted, without delay, with a first-order illuminating apparatus.” In 1854, just two weeks after the old wooden Gay Head Light structure was refitted with the new lighting apparatus – Congress approved $30,000 for the construction of a new brick tower to fit a first-order Fresnel Lens, and to build a new keeper's residence also made of brick. As a result, the existing 51 feet tall conical brick tower that stands today was started in 1854 and lit in 1856.[2] The bricks used to construct the light were composed of clay bricks manufactured at the nine-mile distant Chilmark brickyard. It was equipped with a whale oil fired first-order Fresnel Lens standing about 12 feet (4 m) tall; weighing several tons (tonnes); and containing 1,008 hand-made crystal prisms.

In August, 1854, the United States Congress approved the purchase of a first-order Fresnel Lens for the soon-to-be-built brick tower at Gay Head. Shortly after, the United States Lighthouse Board submitted a purchase order to Lepaute Manufacturing in France for the manufacture of the Fresnel Lens. Lepaute Manufacturing was founded in 1838 by the watchmaker/inventor, Henri Lepaute. Thus, the manufacture of the Fresnel Lens also incorporated a weighted clock mechanism to rotate the lens. In February 1855, upon completion of building the Fresnel Lens, and before shipment to America, Lepaute Manufacturing requested permission from the United States Lighthouse Board to exhibit the lens at the World Fair in Paris. The Lighthouse Board granted permission on March 19, 1855. When the Fresnel Lens was exhibited at the 1855 World's Fair, it won a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition of Industry.[9] On May 13, 1856, the Fresnel Lens was shipped to New York from Le Havre, France to America. Le Havre is a coastal city with frontage along the English Channel. Soon after its arrival in New York, the Fresnel Lens and its accompanying apparatus was shipped from New York to Edgartown. Upon arrival in Edgartown, the Fresnel Lens was transported overland to its final destination in Gay Head.

On July 18, 1855, Caleb King of Boston was awarded the contract to construct the new redbrick tower and its attached redbrick keeper's dwelling. The construction contract stipulated that Caleb King must complete the light-house at Gay Head by the December 1, 1855. At that time in history, Gay Head was listed as the ninth most important lighthouse location in the United States. Therefore, it deservedly became one of the first lighthouses in the United States to receive a Lepaute-manufactured first-order Fresnel lens.[2] Caleb King, fulfilled his contract, and on December 1, 1856, the new Gay Head Lighthouse signal was activated. After illumination, the Gay Head Light Fresnel Lens received considerable publicity. This resulted in many tourists visiting the light via steamship and other transport systems of the period.

As far as the fate of the old wooden Gay Head Light, we only have the following Gazette advertisement from spring of 1857: "AUCTION AT GAY HEAD! The old Lighthouse, a lot of Oil-Buts, and various other articles will be sold to the highest bidder at 12 M. April 14th. By order of Lieut. W. B. Franklin, Engr. Sec'y Light House Board." As of this writing, no other historic information is available relative to what happened to the island's first Gay Head Light that was constructed of wood in 1799.

Due to various factors, the Gazette reported no news of the transoceanic voyage of the Fresnel apparatus to docks in New York, nor of the Fresnel's arrival on Martha's Vineyard in 1856 during the months of June or July. Neither did the Gazette report any news or take any photographs of the transport of the Fresnel lens apparatus across the island, or of the construction of the new lighthouse and the installation of the Fresnel lens. The early 1856 transport of the Fresnel Lens and its supporting apparatus from the docks in Edgartown to the clay cliffs was reported in a reflective story published in the Vineyard Gazette on June 26, 1970: "...It took eight yoke of oxen to transport the heavy iron railing for the catwalks...but it took 40 yoke of oxen to move the 60 frames of glass prisms and the multitudinous collection of machinery necessary to operate the new light. The finely balanced lantern weighed over a ton all told. It must have been a slow ponderous procession that traveled the 20 some odd miles of hard packed dirt and sandy island roads from the Edgartown wharf to the clay cliffs..." Further attesting to the condition of Gay Head roads in the early 1800s, is Martha's Vineyard historian Charles Edward Banks' research published in 1911, ....on the Indian lands there are no made roads, and for the most part only horse paths." This condition existed for about fifty *years more, when a continuation of the county road from the Chilmark line to the lighthouse was laid out. Its construction was without design and unscientific, and soon became a continuous sand rut for lack of repairs. In 1870, when the town was incorporated, the act provided that the county commissioners should forthwith "proceed to lay out and construct a road from Chilmark to the lighthouse on Gay Head, and may appropriate such sum from the funds of the county as may be necessary to defray the expense of the same." It was further provided that it should be maintained for five years by the state. This legislation resulted in the construction of the present and only public highway in the town, which since 1875 has been a town charge."

What this and other early island stories about the Gay Head Light fail to document is the quarry source and transport of the heavy brownstone system that sits atop the brick structure to support the lighting room and its extended balcony. As well, it remains a mystery as to how the early lighthouse builders lifted and emplaced the huge, custom-carved brownstone pieces, as well as the Fresnel lens itself and its heavy cast iron operating apparatus and the internal staircase with its cast-iron landings.

1874–1988

[edit]On May 15, 1874, the Gay Head Light was changed from flashing white to "three whites and one red" to differentiate the light from the area's two other principal lights located at Sankaty Head and Montauk Point. All three lights had Fresnel lenses, however, the Gay Head Light was the only light of the 1st Order. The addition of the red flash signal required the exterior vertical installation of a red screen from top to bottom along every fourth row of prisms of the rotating Fresnel lens. The illuminator of the Fresnel was a lamp with five concentric wicks, the largest being five inches in diameter. The light consumed about two quarts of oil an hour, or about seven and a half gallons on the longest nights. Due to cost savings, the Gay Head Light was converted from increasingly expensive sperm whale oil to lard oil in 1867.[10] In 1885, the Light was converted from lard oil to kerosene oil. Although the Fresnel Lens was invented in Europe in 1822, the U.S. Lighthouse Board did not allow it to be installed in America's lighthouses until the Fresnel underwent a series of tests in Navesink, NJ. Beginning in the early 1850s, Fresnel Lenses were installed in U.S. Lighthouses, with Gay Head Lighthouse receiving one of the first Fresnel Lenses of First Order in 1856. Due to the superiority of the Fresnel Lens to any other lighthouse optic available in the 19th century, the U.S. Lighthouse Board converted all U.S. lighthouses to the Fresnel Lens system by 1860.

Relative to the subject of lighthouse illuminants – the evolution of fuels used in America's lights went as follows: wood fires and candles were replaced by whale oil with solid wicks. Whale oil continued to be used via an improved mechanical delivery system when the parabolic reflector system was introduced around 1810. Whale oil remained the fuel of choice until coiza oil (pressed from wild cabbages) replaced whale oil in the early 1850s. However, due to certain challenges, America's farmers lost interest in growing and manufacturing coiza oil. In the mid-1850s, the U.S. Lighthouse Board switched to lard oil (made from animal fat). Kerosene started replacing lard oil in the early 1870s – with full conversion to kerosene by the late 1880s.[11] Electricity started to replace kerosene around the turn of the 20th century, with Gay Head Light being electrified in 1954.[12]

Keeper Crosby L. Crocker served as lighthouse Keeper from 1892 to 1920. Crocker and his family were reportedly healthy when they moved into the brick Keeper's house in 1892. During the first fifteen months, Crocker had four of his children die under mysterious circumstances. Ten years after the death of his four children, his fifth child, George H. Crocker, died at age fifteen. On similar note, Edward P. Lowe (Keeper 1891–92), who lived at the light prior to Crocker, died after just one year of service. The cause of the deaths was attributed to toxic spores from mold and mildew growing on the damp brick walls inside the house. In 1899 the Lighthouse Board voted that the brick house was "too damp and unsanitary for safe occupation by human beings," and recommended $6,500 for a new house made of wood. As a result, a spacious gambrel-roofed, double dwelling was constructed in 1902.

In 1920, Charles W. Vanderhoop Sr. was appointed as the tenth Principal Lighthouse Keeper. Keeper Vanderhoop had the distinction of being the only Aquinnah Wampanoag Indian to officially tend the Lighthouse. During Vanderhoop's service, the Gay Head Light was well maintained and operated. This was due in large part to the fact that Keeper Charles Vanderhoop acquired valuable working knowledge of the Fresnel lens apparatus when he served as assistant Keeper at Sankaty Head Light. Keeper Charles Vanderhoop was renowned for his story-telling abilities – which entertained visitors touring the Gay Head Lighthouse. According to Charles W. Vanderhoop Jr., when his father gave former President Calvin Coolidge and his friends a tour of the lighthouse – Coolidge nodded his head or smiled from time to time as his friends talked and asked questions. At the end of the tour, Coolidge lingered on the lighthouse balcony overlooking the clay cliffs and Elizabeth Islands. While doing so, Coolidge uttered one word, "Beautiful."

Gay Head was one of the last towns in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to receive electricity in the early 1950s. Shortly after the town received electricity, the Fresnel lens was replaced in 1952 by a high-intensity electrified Carlisle & Finch DCB-224 aero beacon. This beacon was custom-made for the Gay Head Light as a double-tiered cannon beacon to maintain the historic signal of "three whites and one red". By 1956 the Gay Head Light was fully automated – negating the need for a lighthouse Keeper to occupy the property. The 1902 wooden gambrel-roofed Keepers house was razed circa 1960.

When the original Fresnel lens was dismantled in 1952, it was transferred to Edgartown and mounted on top of a one-story brick structure with a glass lantern house enclosure at the Martha's Vineyard Museum in Edgartown, Massachusetts. Charles W. Vanderhoop, who served as the light's Principal Keeper from 1920 to 1933, had the honor of lighting the Fresnel lens at its new location in Edgartown during a dedication ceremony. In 1988, the high-intensity electrified beacon Carlisle & Finch DCB-224 aero beacon was replaced with a single-tiered double cannon high-intensity DCB-224 beacon. With the 1988 installation of the DCB-224 lens, the Gay Head Light's distinctively historic signal of "three whites and one red" was changed to "one white and one red." Ownership of the double-tiered Carlisle & Finch DCB-224 aero beacon was transferred by the United States Coast Guard to Vineyard Environmental Research, Institute, whose board member, Fairleigh S. Dickinson Jr., along with VERI President, William Waterway Marks, presented the light on a loan basis for public display at the Martha's Vineyard Museum.

Saving the Gay Head Light

[edit]

From 1956 to 1985, the automated Gay Head Light was sparingly maintained by the United States Coast Guard. Due to US Coast Guard Congressional funding shortages through the 1970s and early 1980s, several lighthouses around the United States were designated for destruction because the structures were expensive to maintain, and most no longer served as vital aids to navigation. This obsolete designation was precipitated by enhanced satellite GPS and other new maritime navigation aids. In the mid-1980s, due to United States Coast Guard funding shortages, the Gay Head Light along with two other Martha's Vineyard lighthouses (East Chop Light and Edgartown Harbor Light) were listed for destruction. Documentation of lighthouses destroyed in recent history is available from Lighthouse Digest, which maintains a "Doomsday List" of threatened lighthouses. As in other similar lighthouse removal projects, the United States Coast Guard would dismantle or raze the existing lighthouse and, if deemed necessary, replace the light with a low-maintenance iron spindle structure top-mounted with a strobe light.

The three threatened lights on Martha's Vineyard were spared through the objecting federal petition and Congressional testimony of Vineyard Environmental Research, Institute's (VERI) founding President, William Waterway Marks, and VERI Chairperson, John F. Bitzer Jr.[13] VERI was a nonprofit organization co-founded in 1984 by William Waterway Marks and Fairleigh S. Dickinson Jr., to undertake cutting-edge environmental research of acid rain; sea-level rise; coastal erosion; shellfish resources; Great Pond, wetland, and barrier beach ecosystem dynamics, and aquifer (groundwater) protection. In 1984, VERI received the support of Senator Edward Kennedy and Congressman Gerry Studds during and after the Congressional hearings to save the three island lighthouses from being dismantled and/or razed. Following the Congressional hearings, the United States Coast Guard licensed the three lights to VERI in 1985 for thirty-five years.[13] This lighthouse license gave complete control over the management and maintenance of Gay Head Light structure (except the aide to navigation) and its surrounding grounds.

This was the first time in U.S. history that control of "active" lighthouses was transferred to a civilian organization. On similar note, this was the first time in the history of Martha's Vineyard that control of any of its five lighthouses was now in the hands of an island organization. After receiving the lighthouse license, the Institute undertook a series of fundraising activities that engaged the community of Martha's Vineyard, including local supporters and celebrities such as board members: Fairleigh S. Dickinson Jr.; Jonathan Mayhew, whose ancestor's were the Vineyard's first European settlers; Vineyard Gazette co-owner, Jody Reston; philanthropist, Flipper Harris; Margaret K. Littlefield; the actress, Linda Kelsey; WHOI Director, Derek W. Spencer,[14] and John F. Bitzer Jr.. Speakers and performers appearing at these lighthouse events were historian David McCullough; Senator Edward Kennedy; Caroline Kennedy; Edward Kennedy Jr.; Congressman Gerry Studds; singer/songwriter, Carly Simon; Kate Taylor; Livingston Taylor; Hugh Taylor; Dennis Miller from Saturday Night Live; Bill Styron's wife, Rose Styron – who read one of her original lighthouse poems; United States Navy Rear Admiral, Richard A. Bauman;[15] famed photographer, Alfred Eisenstaedt, and comedian, Steve Sweeney.

[13] The proceeds from the lighthouse benefits were applied to a major restoration of the Gay Head Light, which included: emergency pointing of brick walls; removal of pervasive toxic mold growing on the brick interior walls; installing new windows on the ground floor and two landing levels; replacing broken plate glass and sealing roof leaks in the lighting room; restoration of hardwood staircase rail; sandblasting, sealing, and painting of the historic rusted cast-iron spiral staircase and its three-story internal metal flooring and support structure.

In 1987, the Gay Head Light was placed on the National Register of Historic Places (#87001464) as "Gay Head Light," [16] while under management of Vineyard Environmental Research, Institute (VERI) through its United States Coast Guard license number DTCGZ71101-85-RP-007L.

Public access

[edit]

From the earliest days of its history, the Gay Head Light appears as though it welcomed visiting public. Early photographs depict visitors populating the lighthouse balcony and its surrounding grounds. In 1856, after the installation of the famous Fresnel lens, tourism to the lighthouse increased. Special steamship excursions from the Oak Bluffs Wharf took tourists to the Steamboat Landing dock below the Gay Head Cliffs, where waiting oxcarts provided transport to the lighthouse. Circa 1857, Harper's Magazine published an account of a visit to the lighthouse and its powerful new lens by writer David Hunter Strother: "At night we mounted the tower and visited the look-out gallery that belts the lighthouse at some distance below the lantern. Here we were surprised by a unique and splendid spectacle. The whole dome of heaven, from the centre to the horizon, was flecked with bars of misty light, revolving majestically on the axis of the tower. These luminous bars, although clearly defined, were transparent; and we could distinctly see the clouds and stars behind them. Of all the heavenly phenomena that I have had the good fortune to witness — borealis lights, mock suns, or meteoric showers — I have never seen anything that in mystic splendor equaled this trick of the magic lantern at Gay Head." Public access was also documented by historian Edward Rowe Snow, who mentioned how Principal Keeper, Charles W. Vanderhoop, and his assistant, Max Attaquin, "...probably took one-third of a million visitors to the top of Gay Head Light between 1910 and 1933." After the Gay Head Light was electrified and automated in the mid-1950s – the lighthouse's Principal Keeper, Joseph Hindley, vacated the premises circa 1956, and the light was closed to public access.

According to the United States Coast Guard aerial photograph (lower right), and other photographic documentation and research provided by Vineyard Environmental Research, Inst., the following structures were still standing in 1958: the three-story Gambrel-style Keeper's house; a large barn; the square, brick, three-story WWII observation tower; a small, so-called guest house or utility building at the edge of the cliffs, and the WWII concrete bunker just below the guest house. Circa 1960, all buildings except the lighthouse and the concrete World War II bunker were razed. Since 1958, the WWII bunker has slowly slid down the face of the clay cliffs toward the beach at the bottom of the cliffs near the ocean, where it exists today in the ocean's intertidal zone at the base of the cliffs.

In 1985, Vineyard Environmental Research, Institute (VERI), received a 35-year license from the United States Coast Guard to maintain the Gay Head Lighthouse and its surrounding real estate. In 1986, on Mother's Day, VERI reopened the Gay Head Light to the public for the first time since 1956. At the same time, the lighthouse was also made available for weddings and special functions. In 1985, when VERI's founder, William Waterway Marks became the light's Principal Keeper – he appointed his friend, Charles Vanderhoop Jr., as Assistant Keeper, along with abutting lighthouse property owner, Helen Manning. Charles Vanderhoop Jr. was born in the lighthouse while his father, Charles W. Vanderhoop, was serving as Principal Keeper from 1920 to 1933.[13] In 1929, Charles W. Vanderhoop gave a lighthouse tour to President Calvin Coolidge just after his presidency ended.[17] Charles W. Vanderhoop was the only Wampanoag to serve in the position of Keeper until his son, Charles Vanderhoop Jr., was appointed Assistant Keeper in 1986. The Gay Head Light was reopened to the public in 1986 for sunsets on weekends; island school children visits; special events and tours, and weddings. During the late 1980s, various other people from the community were also appointed as modern-day Gay Head Light Assistant Keepers on weekends and special occasions. In 1990, William Waterway Marks appointed Richard Skidmore and his wife, Joan LeLacheur, as Assistant Keepers. Richard and Joan became Principal Keepers in 1994 and remain in that position today. In 1987 VERI also opened the East Chop and Edgartown lights to the public for the first time in many decades.[13]

After the Gay Head Light opened to the public, bus loads of children from all of the island's schools began to visit the light as part of VERI's educational outreach programs.[18]

In 1994, VERI transferred their lighthouse license to the Martha's Vineyard Historical Society (MVHS), which is now known as the Martha's Vineyard Museum. At the time, William Waterway Marks was also serving as a MVHS board member, and was installed as the first Chairman of the newly formed MVHS Lighthouse Committee, where he served for four years from 1994 to 1997.[18]

Today the Gay Head Light is managed by the Martha's Vineyard Museum and is open to the public during the summer season, on special holidays, and for weddings and other private functions. In August, 2009, Principal Keeper, Joan LeLacheur, gave President Barack Obama and his family a private tour during their vacation on Martha's Vineyard.[19] This lighthouse also appears briefly in the background of the movie Jaws as Chief Brody is driving to the beach.[20]

Through dedicated love, labor, and sacrifice of the Martha's Vineyard Community, the Gay Head Light survives today as an iconic symbol of the island's maritime history. While under the management and care of Vineyard Environmental Research, Inst., the Gay Head Light was placed on the National Register of Historic Places (June 15, 1987), and officially recognized by the name of "Gay Head Light". For additional information, see National Register reference number 87001464.,.[1] This historic designation was accomplished while VERI was repairing and restoring the Gay Head Light under its United States Coast Guard License Number DTCGZ71101-85-RP-007L.

Modern-day lighthouse ownership

[edit]

In May 2011, the Gay Head Light was presented in a Vineyard Gazette article as being available for "auction" in the near future. Both Gay Head Light and Edgartown Light were mentioned as being eligible for excess property designation by the United States Coast Guard (USCG), and the General Services Administration (GSA). Such "excessing" of a federal property makes the proposed properties eligible for ownership by local governments, nonprofits, and private interests. Since May 2011, the Martha's Vineyard Museum and the Town of Edgartown have entered into a dialogue with various federal agencies relative to a mutual town/Museum ownership/lease arrangement. According to an October 19, 2012 Vineyard Gazette published comment by David Nathans, Director of the Martha's Vineyard Museum, "...the Museum is not applying for ownership. The Town of Edgartown has applied for ownership, and the Museum is expecting to continue to lease the right and responsibility to steward, interpret and operate the Edgartown Lighthouse. This town and Museum relationship could be the model for the Gay Head Lighthouse as well."[21]

According to the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act (LHPA), any excessed lighthouse is eligible for ownership transfer from the federal government to other federal agencies; state, regional, and local governments; nonprofits, and, as a last resort – auction to private interests. As the current license holder of record – the nonprofit Martha's Vineyard Museum may apply for ownership. As well, the Town of Gay Head and the Wampanoag Tribe may also file for individual or shared ownership/management of the Gay Head Light. In recent years, the Town of Gay Head, via application by the Martha's Vineyard Museum, has expended about $100,000 to help repair and maintain the Gay Head Light. This $100,000 was raised from local funds sourced via the Community Preservation Act (CPA). The CPA is a Massachusetts state law (M.G.L. Chapter 44B) passed in 2000 that enables adopting communities to raise funds to create a fund for open space preservation, preservation of historic resources, development of affordable housing, and the acquisition and development of outdoor recreational facilities.[21]

On August 1, 2013, a federal "NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY" was published in fulfillment of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. The introduction to this notice reads as follows: "The light station described on the attached sheet has been determined to be excess to the needs of the United States Coast Guard, Department of Homeland Security. Pursuant to the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000, 16 U.S.C. 470 (NHLPA), this historic property is being made available at no cost to eligible entities defined as Federal agencies, state and local agencies, non-profit corporations, educational agencies, or community development organizations for educational, park, recreational, cultural or historic preservation purposes.

"Any eligible entity with an interest in acquiring the described property for a use consistent with the purposes stated above should submit a letter of interest to the address listed below within 60 (sixty) days from the date of this Notice."[22] "Pursuant to Section 309 of the NHLPA, the light station will be sold if it is not transferred to a public body or non-profit organization.

Today, due to erosion, the Gay Head Light is surrounded by approximately one acre of plateau land. The transfer of ownership of the Gay Head Light was voted by the LHPA and the GSA to be transferred to the Town of Aquinnah. After relocation of the lighthouse in June 2015 to a new location, the Town of Aquinnah via its "Save the Gay Head Lighthouse Committee," continues to move forward with fundraising efforts to finance the restoration of the light and its grounds.[23][24]

Relocation, 2015

[edit]

The Gay Head Lighthouse Committee worked in conjunction with the town of Aquinnah and the Martha's Vineyard island community to raise approximately $3.5 million to relocate the lighthouse about 129 feet (39 m) from its former location. The lighthouse was relocated by Expert House Movers and the General Contractor, International Chimney.[25]

Prior to relocation, the inside of the lighthouse was reinforced with a combination of cement block; steel beams, and block and tackle equipment. Besides stabilizing the interior of the light - the outside brick wall of the level beneath the lighting room was reinforced with plywood held in place with tightened steel cables. A similar steel cable reinforcement scheme was also used to stabilize the light's granite foundation. A roadway was excavated from the light's existing location to its new location onto a 3-foot thick reinforced footing. A series of heavy steel I-beams established a support base and track on which the lighthouse was pushed and moved with pneumatic power.

Due to the aide-to-navigation requirement that the elevation of the light's signal remain constant - the lower elevation of the new lighthouse location required the light be raised on a cement block foundation. The new cement block foundation along with the light's original granite stone foundation maintain the light's signal at its previous elevation. The new cement block foundation and old granite stone foundation are now buried beneath fill and topsoil. To minimize erosion of the cliffs due to potential drainage through disturbed soils of the excavated area - semi-impervious hardener was compacted (see photo foreground) with heavy vibrating rollers. Top soil and vegetation removed and saved from the original site were then installed to reestablish the vegetated landscape. In preparation of the relocation, the light's flashing red-and-white signal was extinguished by Principal Keeper Richard Skidmore on April 16, 2015. The light was returned to its functional brilliance at 6:08 PM on the stormy evening of August 11, 2015. The Gay Head Lighthouse is once again open for public visitation through the Martha's Vineyard Museum. The new location of the Gay Head Light is approximately 180 feet back from the eroding cliff's face. It has been estimated by engaged geologists that the lighthouse will not be threatened again for another 150 years.[26]

List of keepers

[edit]

- Ebenezer Skiff (Principal Keeper 1799–1828)

- Ellis Skiff (Principal Keeper 1828–1845)

- Samuel H. Flanders (Principal Keeper 1845–1849 and 1853–1861)

- Henry Robinson (Principal Keeper 1849–1853)

- Ichabod Norton Luce (Principal Keeper 1861–1864)

- Calvin C. Adams (Principal Keeper July, 1864–1868)

- James O. Lumbert (Principal Keeper 1868–1869)

- Horatio N. T. Pease (Assistant Keeper 1863–1869, Principal Keeper 1869–1890)

- Frederick H. Lambert (Assistant Keeper c1870-1872)

- Calvin M. Adams (Assistant Keeper c1872-c1880)

- Frederick Poole (Assistant Keeper c1880-1884)

- Crosby L. Crocker (Assistant Keeper c1885-1892)

- William Atchison (Principal Keeper 1890–91)

- Edward P. Lowe (Principal Keeper 1891–1892)

- Crosby L. Crocker (Principal Keeper 1892–1920)

- Leonard Vanderhoop (Assistant Keeper, 1892-c1894) Alonzo D. Fisher – Crosby Crocker's son-in-law (Assistant Keeper 1894–?)

- William A. Howland, (Assistant Keeper, 1897–?)

- Charles Wood Vanderhoop (Principal Keeper 1920–1933)

- Max Attaquin (Assistant Keeper 1920 -1933)

- James E. Dolby (Principal Keeper 1933–1937)

- Frank A. Grieder (Principal Keeper 1937–1948)

- Sam Fuller (Assistant Keeper c.? 1940s)

- Arthur Bettencourt (Principal Keeper 1948–1950)

- Joseph Hindley (Principal Keeper 1950–1956)

- William Waterway Marks (Principal Keeper 1985–1998)

- Charles Vanderhoop Jr. (Assistant Keeper 1985–1990)

- Helen Manning (Assistant Keeper 1985–1990)

- Robert McMahon (Assistant Keeper 1985–1990)

- Todd Follansbee (Assistant Keeper: 2010–2012)

- Richard Skidmore and Joan LeLacheur (Assistant Keepers 1990–98, Principal Keepers 1998–present).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Historic Light Station Information and Photography: Massachusetts". United States Coast Guard Historian's Office. 2009-09-05. Archived from the original on 2017-05-01.

- ^ United States Coast Guard (2009). Light List, Volume I, Atlantic Coast, St. Croix River, Maine to Shrewsbury River, New Jersey. p. 8.

- ^ "Lighthouse History," Martha's Vineyard Magazine, Fall/Winter 1989–90, Page 42, paragraphs 3 & 4.

- ^ a b "Gay Head Lighthouse". US-Lighthouses.com.

- ^ National Archives

- ^ Lighthouses of the Carolinas: A Short History and Guide (Terrance Zepke)

- ^ "Maritime Heritage Program". Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Gay Head Light Gets The Wondrous Fresnel," by: Arthur Railton, The Dukes County Intelligencer, Vol. 23, No. 4, May 1982

- ^ Vineyard Gazette, January 1, 1869

- ^ Kendall, Connie Jo. "Let There Be Light: The History of Lighthouse Illuminants." The Keeper’s Log (Spring 1997)

- ^ Betty Hatzikon letter (December 7, 1982), daughter of Gay Head Light's last Keeper, Joseph Hindley.

- ^ a b c d e "Saving Lighthouses on Martha's Vineyard". Lighthouse Digest. December 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Dawicki, Shelley. "In Memoriam: Derek K. Spencer". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Media Relations Office, WHOI. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Holley, Joe. "Richard Arnold Bauman". Coast Guard Admiral Richard A. Bauman Dies. The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "National Register of Historical Places – MASSACHUSETTS (MA), Dukes County". Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Welcome Mr. President!!!". Martha's Vineyard Magazine. August 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ a b "Local school children gathered at the dedication of Gay Head Lighthouse Park". Lighthouse Digest. December 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Becklius, Kim Knox. "President Obama Vacations on Martha's Vineyard". About Travel. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ Jaws, 30th Anniversary Edition (DVD). Universal Pictures. Event occurs at 7:29. ISBN 1-4170-5776-9.

- ^ a b "Old Gay Head Light May Be Auctioned By Government". Vineyard Gazette. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Maritime Heritage Program | National Park Service" (PDF). Cr.nps.gov. Retrieved 2017-09-19.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Aquinnah Seeks Islandwide Aid to Save Gay Head Light". Vineyard Gazette. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Gay Head Lighthouse - Martha's Vineyard". Gayheadlight.org. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

- ^ Alex Elvin (2015-05-28). "Martha's Vineyard News | Day One for Gay Head Light Move: 1856 Brick Tower Travels 52 Feet". The Vineyard Gazette. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

- ^ Wright, Beverly (September 3, 2015). "Light Shines On". Vineyard Gazette. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

External links

[edit]- Lighthouses completed in 1799

- Lighthouses completed in 1856

- Martha's Vineyard

- Lighthouses on the National Register of Historic Places in Massachusetts

- National Register of Historic Places in Dukes County, Massachusetts

- Buildings and structures in Aquinnah, Massachusetts

- 1799 establishments in Massachusetts

- Aquinnah, Massachusetts

- Wampanoag