Grace Jones

Grace Jones | |

|---|---|

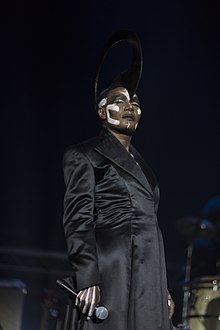

Jones in performance, 2015 | |

| Born | Grace Beverly Jones 19 May 1948 Spanish Town, Saint Catherine, Jamaica |

| Other names | Grace Mendoza |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Onondaga Community College |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1973–present |

| Works | Discography |

| Spouse | Atila Altaunbay

(m. 1996–2004) |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Noel Jones (brother) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instrument | Vocals |

| Labels | |

| Website | www |

Grace Beverly Jones OJ (born 19 May 1948) is a Jamaican singer, songwriter, model and actress.[13] Born in Jamaica, she and her family moved to Syracuse, New York, when she was a teenager. Jones began her modelling career in New York state, then in Paris, working for fashion houses such as Yves St. Laurent and Kenzo, and appearing on the covers of Elle and Vogue. She notably worked with photographers such as Jean-Paul Goude, Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, and Hans Feurer, and became known for her distinctive androgynous appearance and bold features.

Beginning in 1977, Jones embarked on a music career, securing a record deal with Island Records and initially becoming a high-profile figure of New York City's Studio 54-centered disco scene. In the early 1980s, she moved toward a new wave style that drew on reggae, funk, post-punk, and pop music, frequently collaborating with both the graphic designer Jean-Paul Goude and the musical duo Sly & Robbie. She scored Top 40 entries on the UK Singles Chart with "Private Life", "Pull Up to the Bumper", "I've Seen That Face Before", and "Slave to the Rhythm". In 1982, she released the music video collection A One Man Show, directed by Goude, which earned her a nomination for Best Video Album at the 26th Annual Grammy Awards. Her most popular albums include Warm Leatherette (1980), Nightclubbing (1981), and Slave to the Rhythm (1985).

As an actress, Jones appeared in several indie films prior to landing her first mainstream appearance as Zula in the fantasy-action film Conan the Destroyer (1984) alongside Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sarah Douglas, and subsequently appeared in the James Bond movie A View to a Kill (1985) as May Day, and starred as a vampire in Vamp (1986); all of which earned her nominations for the Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actress. In 1992, Jones acted in the Eddie Murphy film Boomerang, and contributed to the soundtrack. She also appeared alongside Tim Curry in the 2001 film Wolf Girl.

Jones was ranked 82nd on VH1's 100 Greatest Women of Rock and Roll (1999). In 2008, she was honored with a Q Idol Award. Jones influenced the cross-dressing movement of the 1980s and has been cited as an inspiration for multiple artists, including Annie Lennox, Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Solange, Lorde, Róisín Murphy, Brazilian Girls, Nile Rodgers, Santigold, and Basement Jaxx. In 2016, Billboard ranked her as the 40th greatest dance club artist of all time.[12]

Biography and career

1948–1973: Early life, and modeling career

Grace Jones was born in 1948 (though most sources say 1952)[4][14][15][16] in Spanish Town, Jamaica, to Marjorie (née Williams) (1927–2017)[17][18] and Robert W. Jones (1925–2008),[19] who was a local politician and Apostolic clergyman.[20][21][22][23] The couple already had two children, and would go on to have four more.[24] Robert and Marjorie moved to the East Coast of the United States,[24] where Robert worked as an agricultural labourer until a spiritual experience during a suicide attempt inspired him to become a Pentecostal minister.[25] While they were in the US, they left their children with Marjorie's mother and her new husband, Peart.[26] Jones knew him as "Mas P" ('Master P') and later noted that she "absolutely hated him"; as a strict disciplinarian he regularly beat the children in his care, representing what Jones described as "serious abuse".[27] She was raised into the family's Pentecostal faith,[28] having to take part in prayer meetings and Bible readings every night.[29] She initially attended the Pentecostal All Saints School,[30] before being sent to a nearby public school.[31] As a child, Jones was shy and had only one schoolfriend. She was teased by classmates for her "skinny frame", but she excelled at sports and found solace in the nature of Jamaica.[32]

[My childhood] was all about the Bible and beatings. We were beaten for any little act of dissent, and hit harder the worse the disobedience. It formed me as a person, my choices, men I have been attracted to... It was a profoundly disciplined, militant upbringing, and so in my own way, I am very militant and disciplined. Even if that sometimes means being militantly naughty, and disciplined in the arts of subversion.

Grace Jones, 2015[33]

Marjorie and Robert eventually brought their children – including the 13 year-old Grace – to live with them in the US, where they had settled in Lyncourt, Salina, New York, near Syracuse.[34][35] It was in the city that her father had established his own ministry, the Apostolic Church of Jesus Christ, in 1956.[36] Jones continued her schooling and after she graduated, enrolled at Onondaga Community College majoring in Spanish.[37][38] Jones began to rebel against her parents and their religion; she began wearing makeup, drinking alcohol, and visiting gay clubs with her brother.[39] At college, she also took a theatre class, with her drama teacher convincing her to join him on a summer stock tour in Philadelphia.[40][38] Arriving in the city, she decided to stay there, immersing herself in the Counterculture of the 1960s by living in hippie communes, earning money as a go-go dancer, and using LSD and other drugs.[41] She later praised the use of LSD as "a very important part of my emotional growth... The mental exercise was good for me".[42]

She moved back to New York at 18 and signed on as a model with Wilhelmina Models. She moved to Paris in 1970.[38][43] The Parisian fashion scene was receptive to Jones's unusual, androgynous, bold, dark-skinned appearance. Yves St. Laurent, Claude Montana, and Kenzo Takada hired her for runway modelling, and she appeared on the covers of Elle, Vogue, and Stern working with Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, and Hans Feurer.[44] Jones also modelled for Azzedine Alaia, and was frequently photographed promoting his line. While modelling in Paris, she shared an apartment with Jerry Hall and Jessica Lange. Hall and Jones frequented Le Sept, one of Paris's most popular gay clubs of the 1970s and 1980s, and socialised with Giorgio Armani and Karl Lagerfeld.[45] In 1973, Jones appeared on the cover of a reissue of Billy Paul's 1970 album Ebony Woman.

1974–1979: Transition to music, and early releases

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

Jones was signed by Island Records, who put her in the studio with disco record producer, Tom Moulton. Moulton worked at Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, and Portfolio, was released in 1977. The album featured three songs from Broadway musicals, "Send in the Clowns" by Stephen Sondheim from A Little Night Music, "What I Did for Love" from A Chorus Line and "Tomorrow" from Annie. The second side of the album opens up with a seven-minute reinterpretation of Édith Piaf's "La Vie en rose" followed by three new recordings, two of which were co-written by Jones, "Sorry", and "That's the Trouble". The album finished with "I Need a Man", Jones's first club hit.[46] The artwork to the album was designed by Richard Bernstein, an artist for Interview.

In 1978, Jones and Moulton made Fame, an immediate follow-up to Portfolio, also recorded at Sigma Sound Studios. The album featured another reinterpretation of a French classic, "Autumn Leaves" by Jacques Prévert. The Canadian edition of the vinyl album included another French language track, "Comme un oiseau qui s'envole", which replaced "All on a Summers Night"; in most locations this song served as the B-side of the single "Do or Die". In the North American club scene, Fame was a hit album and the "Do or Die"/"Pride"/"Fame" side reached top 10 on both the US Hot Dance Club Play and Canadian Dance/Urban charts. The album was released on compact disc in the early 1990s, but soon went out of print. In 2011, it was released and remastered by Gold Legion, a record company that specialises in reissuing classic disco albums on CD.

Jones's live shows were highly sexualized and flamboyant, leading her to be called "Queen of the Gay Discos."[6]

In the same year she was cast in the highly controversial Italian TV program Stryx, aired by Rai 2, where she portrayed the character of Rumstryx.[47][48][49]

Muse was the last of Jones's disco albums. The album features a re-recorded version "I'll Find My Way to You", which Jones released three years prior to Muse. Originally appearing in the 1976 Italian film, Colt 38 Special Squad in which Jones had a role as a club singer, Jones also recorded a song called "Again and Again" that was featured in the film. Both songs were produced by composer Stelvio Cipriani. Icelandic keyboardist Thor Baldursson arranged most of the album and also sang duet with Jones on the track "Suffer". Like the last two albums, the cover art is by Richard Bernstein. Like Fame, Muse was later released by Gold Legion.

1980–1985: Breakthrough, Nightclubbing, and acting

With anti-disco sentiment spreading, and with the aid of the Compass Point All Stars, Jones transitioned into new wave music with the 1980 release of Warm Leatherette. The album included covers of songs by The Normal ("Warm Leatherette"), The Pretenders ("Private Life"), Roxy Music ("Love Is the Drug"), Smokey Robinson ("The Hunter Gets Captured by the Game"), Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers ("Breakdown") and Jacques Higelin ("Pars"). Sly Dunbar revealed that the title track was also the first to be recorded with Jones.[50][51] Tom Petty wrote the lyrics to "Breakdown", and he also wrote the third verse of Jones's reinterpretation.[52] The album included one song co-written by Jones, "A Rolling Stone". Originally, "Pull Up to the Bumper" was to be included on the album, but its R&B sound did not fit with the rest of the material.[53] By 1981, she had begun collaborating with photographer and graphic designer Jean-Paul Goude, with whom she also had a relationship.[54] An extended version of "Private Life" was released as a single, with a cover of the Joy Division song "She's Lost Control", a non-album track, as the B-side.

The 1981 release of Nightclubbing included Jones's covers of songs by Flash and the Pan ("Walking in the Rain"), Bill Withers ("Use Me"), Iggy Pop/David Bowie ("Nightclubbing") and Ástor Piazzolla ("I've Seen That Face Before"). Three songs were co-written by Jones: "Feel Up", "Art Groupie" and "Pull Up to the Bumper". Sting wrote "Demolition Man"; he later recorded it with The Police on the album Ghost in the Machine. "I've Done It Again" was written by Marianne Faithfull. The strong rhythm featured on Nightclubbing was produced by Compass Point All Stars, including Sly and Robbie, Wally Badarou, Mikey Chung, Uziah "Sticky" Thompson and Barry Reynolds. The album entered in the Top 5 in four countries, and became Jones's highest-ranking record on the US Billboard mainstream albums and R&B charts.

Nightclubbing claimed the number 1 slot on NME's Album of the Year list.[55] Slant Magazine listed the album at No. 40 on its list of Best Albums of the 1980s.[56] Nightclubbing is now widely considered Jones's best studio album.[57] The album's cover art is a painting of Jones by Jean-Paul Goude. Jones is presented as a man wearing an Armani suit jacket, with a cigarette in her mouth and a flattop haircut. While promoting the album, Jones slapped chat-show host Russell Harty live on air after he had turned to interview other guests, making Jones feel she was being ignored.[58]

Having already recorded two reggae-oriented albums under the production of Compass Point All Stars, Jones went to Nassau, Bahamas in 1982 and recorded Living My Life; the album resulted in Jones's final contribution to the Compass Point trilogy, with only one cover, Melvin Van Peebles's "The Apple Stretching". The rest were original songs; "Nipple to the Bottle" was co-written with Sly Dunbar, and, apart from "My Jamaican Guy", the other tracks were collaborations with Barry Reynolds. Despite receiving a limited single release, the title track was left off the album. Further session outtakes included "Man Around the House" (Jones, Reynolds) and a cover of "Ring of Fire", written by June Carter Cash and Merle Kilgore and popularized by Johnny Cash, both of which were included on the 1998 compilation Private Life: The Compass Point Sessions. The album's cover art resulted from another Jones/Goude collaboration; the artwork has been described as being as famous as the music on the record.[59] It features Jones's disembodied head cut out from a photograph and pasted onto a white background. Jones's head is sharpened, giving her head and face an angular shape.[60] A piece of plaster is pasted over her left eyebrow, and her forehead is covered with drops of sweat.

Jones's three albums under the production of the Compass Point All Stars resulted in Jones's One Man Show, a performance art/pop theatre presentation devised by Goude and Jones in which she also performed tracks from the albums Portfolio ("La Vie en rose"), Warm Leatherette, ("Private Life", "Warm Leatherette"), Nightclubbing ("Walking in the Rain", "Feel Up", "Demolition Man", "Pull Up to the Bumper" and "I've Seen That Face Before (Libertango)") and from Living My Life, "My Jamaican Guy" and the album's title track. Jones dressed in elaborate costumes and masks (in the opening sequence as a gorilla) and alongside a series of Grace Jones lookalikes. A video version, filmed live in London and New York City and completed with some studio footage, was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Long-Form Music Video the following year.[61]

After the release of Living My Life, Jones took on the role of Zula the Amazonian in Conan the Destroyer (1984) and was nominated for a Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actress. In 1985, Jones starred as May Day, henchwoman to main antagonist Max Zorin in the 14th James Bond film A View to a Kill; Jones was also nominated for a Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actress. That same year, she was featured on the Arcadia song "Election Day". Jones was among the many stars to promote the Honda Scooter; other artists included Lou Reed, Adam Ant, and Miles Davis.[62] Jones also, with her boyfriend Dolph Lundgren posed nude for Playboy.[63]

1986–1989: Slave to the Rhythm, Island Life, and further films

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

After Jones's success as a mainstream actress, she returned to the studio to work on Slave to the Rhythm, the last of her recordings for Island. Bruce Woolley, Simon Darlow, Stephen Lipson and Trevor Horn wrote the material, and it was produced by Horn and Lipson. It was a concept album that featured several interpretations of the title track. The project was originally intended for Frankie Goes to Hollywood as a follow-up to "Relax", but was given to Jones.[64] All eight tracks on the album featured excerpts from a conversation with Jones, speaking about many aspects of her life. The interview was conducted by journalist Paul Morley. The album features voice-overs from actor Ian McShane reciting passages from Jean-Paul Goude's biography Jungle Fever. Slave to the Rhythm was successful in German-speaking countries and in the Netherlands, where it secured Top 10 placings. It reached number 12 on the UK Albums Chart in November 1985 and became the second-highest-ranking album released by Jones.[65][66] Jones earned an MTV Video Music Award nomination for the title track's music video.

After her success with Slave to the Rhythm, Island released Island Life, Jones's first best-of compilation, which featured songs from most of her releases with Island (Portfolio, Fame, Warm Leatherette, Nightclubbing, Living My Life and Slave to the Rhythm). American writer and journalist Glenn O'Brien wrote the essay for the inlay booklet. The compilation charted in the UK, New Zealand and the United States.[67] The artwork on the cover of the compilation was of another Jones/Goude collaboration; it featured Jones's celestial body in a montage of separate images, following Goude's ideas on creating credible illusions with his cut-and-paint technique. The body position is anatomically impossible.[68]

The artwork, a piece called "Nigger Arabesque" was originally published in the New York magazine in 1978, and was used as a backdrop for the music video of Jones's hit single "La Vie en rose".[69] The artwork has been described as "one of pop culture's most famous photographs".[70] The image was also parodied in Nicki Minaj's 2011 music video for "Stupid Hoe", in which Minaj mimicked the pose.[71]

After Slave to the Rhythm and Island Life, Jones started to record again under a new contract with Manhattan Records, which resulted in Inside Story, Jones teamed up with music producer Nile Rodgers of Chic, whom Jones had previously tried to work with during the disco era.[72] The album was recorded at Skyline Studios in New York and post-produced at Atlantic Studios and Sterling Sound. Inside Story was the first album Jones produced, which resulted in heated disputes with Rodgers. Musically, the album was more accessible than her previous albums with the Compass Point All Stars, and explored different styles of pop music, with undertones of jazz, gospel, and Caribbean sounds. All songs on the album were written by Jones and Bruce Woolley. Richard Bernstein teamed up with Jones again to provide the album's artwork. Inside Story made the top 40 in several European countries. The album was Jones's last entry to date on US Billboard 200 albums chart. The same year, Jones starred as Katrina, an Egyptian queen vampire in the vampire film Vamp. For her work in the film, Jones was awarded a Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actress.

In 1987, Jones appeared in two films, Straight to Hell, and Mary Lambert's Siesta, for which Jones was nominated for Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Supporting Actress. Bulletproof Heart was released in 1989, produced by Chris Stanley, who co-wrote, and co-produced the majority of the songs, and was featured as a guest vocalist on "Don't Cry Freedom". Robert Clivillés and David Cole of C+C Music Factory produced some tracks on the album.

1990–2004: Boomerang, soundtracks, and collaborations

In 1990, Jones appeared as herself in the documentary, Superstar: The Life and Times of Andy Warhol. 1992 saw Jones starring as Helen Strangé, in the Eddie Murphy film Boomerang, for which she also contributed the song "7 Day Weekend" to its soundtrack. Jones released two more soundtrack songs in 1992; "Evilmainya", recorded for the film Freddie as F.R.O.7, and "Let Joy and Innocence Prevail" for the film Toys. In 1994, she was due to release an electro album titled Black Marilyn with artwork featuring the singer as Marilyn Monroe. "Sex Drive" was released as the first single in September 1993, but the album was shelved due to Jones disliking the mixes that were presented by producers, whom she felt were primarily interested in sampling and had "minced" her vocals. Jones stated that the experience turned her off working on music.[73] The track "Volunteer", recorded during the same sessions, leaked in 2009.[74] In 1995, Jones reunited with Tom Moulton for a disco-house take on Candi Staton's 1978 song "Victim", however, the song's release was cancelled by Island Records.[75][76]

In 1996, Jones released "Love Bites", an up-tempo electronic track to promote the Sci-Fi Channel's Vampire Week, which consisted of a series of vampire-themed films aired on the channel in early November 1996. The track features Jones singing from the perspective of a vampire. The track was released as a non-label promo-only single. As of 2013[update], it had not been made commercially available.[77]

In June 1998, Jones was scheduled to release an album titled Force of Nature, on which she worked with trip hop musician Tricky.[78] The release of Force of Nature was cancelled due to a disagreement between the two, and only a white label 12" single featuring two dance mixes of "Hurricane" was issued at the time;[79] a slowed-down version of this song became the title track of her comeback album released ten years later while another unreleased track from the album, "Clandestine Affair" (recycling the chorus from her unreleased 1993 track "Volunteer"), appeared on a bootleg 12" in 2004.[80] Jones recorded the track "Storm" in 1998 for the movie The Avengers, and in 1999, appeared in an episode of the Beastmaster television series as the Umpatra Warrior.

The same year, Jones recorded "The Perfect Crime", an up-tempo song for Danish TV written by the composer duo Floppy M. aka Jacob Duus and Kåre Jacobsen. Jones was also ranked 82nd place on VH1's "100 Greatest Women of Rock & Roll".[citation needed] In 2000, Jones collaborated with rapper Lil' Kim, appearing on the song "Revolution" from her album The Notorious K.I.M..[81] In 2001, Jones starred in the film, Wolf Girl (also known as Blood Moon), as an intersex circus performer named Christoph/Christine. In 2002, Jones joined Luciano Pavarotti on stage for his annual Pavarotti and Friends fundraiser concert to support the United Nations refugee agency's programs for Angolan refugees in Zambia. In November 2004, Jones sang "Slave to the Rhythm" at a tribute concert for record producer Trevor Horn at London's Wembley Arena.[82][83]

2008–2015: Hurricane and memoir

Despite several comeback attempts throughout the 1990s, Jones's next full-length record was released almost twenty years later, after Jones decided "never to do an album again,"[84] changing her mind after meeting music producer Ivor Guest through a mutual friend, milliner Philip Treacy. After the two became acquainted, Guest let Jones listen to a track he had been working on, which became "Devil in My Life", once Jones set the lyrics to the song. The lyrics to the song were written after a party in Venice.[85]

The two ended up with 23 tracks. The album, Hurricane, included autobiographical songs, such as "This Is", "Williams' Blood" and "I'm Crying (Mother's Tears)", an ode to her mother Marjorie. "Love You to Life" was another track based on real events and "Corporate Cannibal" referred to corporate capitalism. "Well Well Well" was recorded in memory of Alex Sadkin, member of Compass Point All Stars who had died in a motor accident 1987. "Sunset Sunrise" was written by Jones's son, Paulo; the song ponders the relationship between mankind and mother nature. Four songs were removed from the album, "The Key to Funky", "Body Phenomenon", "Sister Sister" and "Misery". For the production of the album, Jones teamed up with Sly and Robbie, Wally Badarou, Barry Reynolds, Mikey Chung, and Uziah "Sticky" Thompson, of the Compass Point All Stars, with contributions from trip-hop artist Tricky, and Brian Eno.[86]

The album was released on Wall of Sound on 3 November 2008, in the United Kingdom. PIAS, the umbrella company of Wall of Sound, distributed Hurricane worldwide excluding North America.[87] The album scored 72 out of 100 on review aggregator Metacritic.[88] Prior to the album's release, Jones performed at Massive Attack's Meltdown festival in London on 19 June 2008, Jones performed four new songs from the album and premiered the music video which Jones and artist Nick Hooker collaborated on, which resulted in "Corporate Cannibal".[89][90][91] Jones promoted the album even further by appearing on talk show Friday Night with Jonathan Ross, performed at several awards galas, and embarked on The Hurricane Tour. The same year, Jones was honoured with Q Idol Award.

In 2009, Chris Cunningham produced a fashion shoot for Dazed & Confused using Jones as a model to create "Nubian versions" of Rubber Johnny.[92] In an interview for BBC's The Culture Show, it was suggested that the collaboration may expand into a video project. Jones also worked with the avant-garde poet Brigitte Fontaine on a duet named "Soufi" from Fontaine's album Prohibition released in 2009, and produced by Ivor Guest.

In March 2010 Jones performed for guests at the 18th annual Elton John AIDS Foundation Academy Award Viewing Party. The Elton John AIDS Foundation is one of the world's leading nonprofit organisations supporting HIV prevention programs, and works to eliminate the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV/AIDS. The event raised US$3.7 million.[93][94] The same year, a budget DVD version of A One Man Show was released, as Grace Jones – Live in Concert. It included three bonus video clips ("Slave to the Rhythm", "Love Is the Drug" and "Crush".

In 2011, Jones collaborated again with Brigitte Fontaine on two tracks from her release entitled L'un n'empêche pas l'autre and performed at the opening ceremony of the 61st FIFA Congress.[95] Jones released a dub version of the album, Hurricane – Dub, which came out on 5 September 2011. The dub versions were made by Ivor Guest, with contributions from Adam Green, Frank Byng, Robert Logan and Ben Cowan.

In April 2012, Jones joined Deborah Harry, Bebel Gilberto, and Sharon Stone at the Inspiration Gala in São Paulo, Brazil, raising $1.3 million for amfAR (the Foundation for AIDS Research). Jones closed the evening with a performance of "La Vie en Rose" and "Pull Up to the Bumper".[96] Two months later, Jones performed "Slave to the Rhythm" at the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II (whilst keeping a hula hoop spinning round her waist throughout), and the Lovebox Festival.[97] On 27 October 2012, Jones performed her only North American show of 2012, a performance at New York City's Roseland Ballroom.[98] The same year, Jones presented Sir Tom Jones with not only the GQ Men of the Year award, but her underwear. Tom Jones accepted the gift in good humour, and replied by saying, "I didn't think you wore any".[99]

Universal Music Group released a deluxe edition of her Nightclubbing album as a two-disc set and Blu-ray audio on 28 April 2014. The set contains most of the 12" mixes of singles from that album, plus two previously unreleased tracks from the Nightclubbing sessions, including a cover of the Gary Numan track "Me! I Disconnect from You".

In October 2014, Jones was announced as having contributed a song, "Original Beast", to the soundtrack of The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1.[100]

Jones's memoir entitled I'll Never Write My Memoirs was released on 29 September 2015.[101]

2017–present: Collaborations and festivals

In 2017, Jones collaborated with British virtual band Gorillaz, appearing on the song "Charger" from their fifth studio album Humanz.[102]

In October 2018, Jones received the Order of Jamaica from the Jamaican government.[103]

In June 2022, Jones served as curator of the 27th edition of the Meltdown Festival, the UK's longest-running artist-curated music festival.[104][105] Jones had been announced as the curator already for the 2020 festival, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic it was rescheduled to 2022.[106] During her show that closed the festival, Jones announced that a brand new 'African hybrid' record was in production, and previewed "The Sun Shines in Wartime" (or "Sunshine In Wartime) and "Blacker Than Black" (or "Born Black") from the album.[107]

Jones provided guest vocals on Beyoncé's song "Move" from her seventh studio album Renaissance, released in July 2022.[108]

On 14 November 2022, music festival Camp Bestival announced their 2023 lineup, which included Jones, alongside Primal Scream, Melanie C, Craig David, The Kooks, the Human League, and others.[109][110]

On 23 July 2023, Jones headlined the music acts at Bluedot Festival. [111] [112]

Artistry and influence

Image

"Grace was very open. We worked together to create this intimidating character. I mean, she's naturally intimidating anyway with her body shape, very straight neck, prominent cheekbones, and clean-cut jawline. She's feminine, no doubt about that, but I've always thought that she was far more beautiful without the artifices she employed to make herself more feminine. I tried to emphasize that body shape through a sort of minimalist German expressionism, with its games of shadows and its angular shapes. Grace is from Jamaica, so she speaks English in a quite thought-out way. I also advised her to address her audience – mostly composed of homosexuals – like a teacher would, with severity. All of that stuff contributed to the building of her image. "

— Jean-Paul Goude, Vice, 2012.[113]

Jones' "appearance was equally divisive" as the sonic fluidity of her music - with her "striking visuals [leading] to her becoming a muse for the likes of Issey Miyake and Thierry Mugler.[114] Her image has been described as "neo-cubist".[115] Jones's distinctive androgynous appearance, square-cut, angular padded clothing, manner, and height of 179 cm (5′ 10+1⁄2″)[citation needed] influenced the cross-dressing movement of the 1980s. To this day, she is known for her unique look at least as much as she is for her music[116] and has been an inspiration for numerous artists, including Annie Lennox,[117] Lorde,[118] Rihanna,[119] Lady Gaga,[120] Nicki Minaj,[121] and Nile Rodgers.[122] Jones was listed as one of the 50 best-dressed over 50 by The Guardian in March 2013.[123]

Kyle Munzenrieder of W magazine wrote that "everyone from Madonna to Björk to Beyoncé to Lady Gaga has taken more than a few pages from her playbook".[124] Jones's work is often discussed for its visual aspect, which was largely the work of French illustrator, photographer, and graphic designer Jean-Paul Goude. According to Jake Hall of i-D, "their collaborative work [went on] to define the visual landscape of the 70s and 80s," and Goude "helped create one of the most intriguing legends in musical history."[114] Goude saw Jones as his muse, declaring she was "beautiful and grotesque at the same time,"[125] and dated her from 1977 to 1984. He "[designed her] album covers, [...] directed her music videos, choreographed live performances, and helped develop her image."[126]

Jones was featured prominently in Goude's work from that period, "which, over the course of the '80s, became increasingly synonymous with willful distortion" - using a technique he refers to as "French correction".[126] The artist stated in 2012: "chopping up photos and rearranging them in a montage to elongate limbs or exaggerate the size of someone's head or some other aspect appealed to me on a lot of levels – I'm always searching for equilibrium, symmetry, and rhythm in an image."[113] Goude's work "centers around artistic depictions of race, ethnicity, and global culture", with an "enchantment with the far-away and the exotic".[114] As a result, much of his depictions of black women are considered controversial and exploitative,[114][125] as Jones was presented as "a white man's rendition of the African feminine."[115] Goude's images depicted her hypersexualized and androgynous, emphasizing her "blackness" and Jamaican heritage. Writer Abigail Gardner felt Jones' body "was presented and manipulated in ways that are clearly congruent with conceiving of that display as artefactual."[115] Essentially, Hall writes, "Goude treated Jones as an artistic vehicle first and foremost - a hyperbole which, despite destroying their personal relationship, allowed Goude to translate his grandiose vision of Jones the phenomenon into a series of imagery which painted her as a surreal, impossible muse."[114]

It has been noted that Jones' ties with the 1970s and 1980s New York art scene are important in understanding her visual identity during this period, and she was close to Andy Warhol, who created a number of paintings and other works of the singer.[127][128] She also knew artist Richard Bernstein, and artist and social activist Keith Haring, who painted her head-to-toe for a series of photographs taken by Robert Mapplethorpe and for her role in the 1986 film Vamp.[129][130][131][128]

In 2020, the first ever art exhibition centred around Jones was presented at Nottingham Contemporary in the United Kingdom, in an attempt to represent "a multi-faceted pop culture icon while trying to reformulate an alternative image of Grace Jones that does not fall into clichés."[132]

Music

Vice described Jones's musical output as "weird, vibrant and progressive," stating that she "has woven disco, new wave, post-punk, art pop, industrial, reggae, and gospel into a tight sound that is distinctly hers, threaded together with lilting, powerful vocals."[133] Her early music was rooted in disco. She opted for a new wave sound in the early 1980s. She recorded a series of albums (1980's Warm Leatherette through 1982's Living My Life) backed by the Jamaica rhythm section duo Sly and Robbie. Her music during this era was described as a new wave hybrid of reggae, funk, pop, and rock.[7] According to John Doran of BBC Music, Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing were "post-punk pop" albums that, "delved into the worlds of disco, reggae and funk much more successfully than most of her 'alternative' contemporaries, while still retaining a blank-eyed alienation that was more reminiscent of David Bowie or Ian Curtis than most of her peers."[134]

Jones has a contralto vocal range. She sings in two modes: either in her monotone speak-sing voice as in songs such as "Private Life", "Walking in the Rain" and "The Apple Stretching", or in an almost-soprano mode in songs such as "La Vie en Rose", "Slave to the Rhythm", and "Victor Should Have Been a Jazz Musician".[135]

Personal life

Jones's father, Bishop Robert W. Jones, was strict and their relationship was strained. According to his particular denomination's beliefs, one should only use one's singing ability to glorify God.[32] He died on 7 May 2008.[21] Her mother, Marjorie, always supported Jones's career (she sings on "Williams' Blood" and "My Jamaican Guy") but could not be publicly associated with her music.[32] Marjorie's father, John Williams, was also a musician[136] and played with Nat King Cole.[32]

Jones described her childhood as having been "crushed underneath the Bible",[37] and since has refused to enter a Jamaican church due to her bad childhood experiences.[137]

Jones used the surname "Mendoza" in her 20s, so that her parents would not know that she was working as a go-go dancer.[138]

Through her relationship with longtime collaborator Jean-Paul Goude, Jones has one son, Paulo, born 12 November 1979. From Paulo, Jones has one granddaughter.[135] Jones married Atila Altaunbay in 1996. She disputes rumors that she married Chris Stanley in her 2015 memoir I'll Never Write My Memoirs, saying, "The truth is, I only ever married one of my boyfriends, Atila Altaunbay, a Muslim from Turkey." She spent four years with Swedish actor Dolph Lundgren, her former bodyguard;[139] she got him a part as a KGB officer in A View to a Kill (1985).[140] Jones started dating Danish actor and stuntman Sven-Ole Thorsen in 1990, and was in an open relationship as of 2007.[141]

Jones's brother is megachurch preacher Bishop Noel Jones, who starred on the 2013 reality show Preachers of LA.[142]

Discography

Studio albums

- Portfolio (1977)

- Fame (1978)

- Muse (1979)

- Warm Leatherette (1980)

- Nightclubbing (1981)

- Living My Life (1982)

- Slave to the Rhythm (1985)

- Inside Story (1986)

- Bulletproof Heart (1989)

- Hurricane (2008)

Tours

- A One Man Show (1981)

- Grace in Your Face (1990)

- Hurricane Tour (2009)[143]

Filmography

| As actress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Title | Role | Notes | |

| 1973 | Gordon's War | Mary | ||

| 1976 | Attention les yeux! | Cuidy | ||

| Quelli della Calibro 38 | Club Singer | Uncredited | ||

| 1978 | Stryx | Rumstryx | TV series | |

| 1981 | Deadly Vengeance | Slick's girlfriend | ||

| 1984 | Conan the Destroyer | Zula | ||

| 1985 | A View to a Kill | May Day | ||

| 1986 | Vamp | Katrina | ||

| 1987 | Straight to Hell | Sonya | ||

| Siesta | Conchita | |||

| 1992 | Boomerang | Helen Strangé | ||

| 1992 | Freddie as F.R.O.7 | Messina (singing voice) | ||

| 1995 | Cyber Bandits | Masako Yokohama | ||

| 1998 | McCinsey's Island | Alanso Richter | ||

| Palmer's Pick Up | Ms. Remo | |||

| 1999 | BeastMaster | Nokinja | Episode: "The Umpatra" | |

| 2001 | Wolf Girl | Christoph/Christine | ||

| Shaka Zulu: The Citadel | The Queen | TV movie | ||

| 2006 | No Place Like Home | Dancer | ||

| 2008 | Falco – Verdammt, wir leben noch! | Waitress | ||

| Chelsea on the Rocks | Bev | |||

| 2016 | Gutterdämmerung | Death / The Devil | ||

| Video games | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Title | Role | Notes | |

| 1994 | Hell: A Cyberpunk Thriller | Solene Solux | ||

| Stage work | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Title | Role | Location | |

| 1997 | The Wiz | Evillene | US Touring Revival | |

| As musician | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Title | Notes |

| 1982 | A One Man Show | "Warm Leatherette" (intro includes excerpts from "Nightclubbing"), "Walking in the Rain", "Feel Up" "La Vie en rose", "Demolition Man", "Pull Up to the Bumper", "Private Life", "My Jamaican Guy", "Living My Life", "I've Seen That Face Before (Libertango)" |

| 1983 | The Video Singles | Includes the videos for "Pull Up to the Bumper", "Private Life" and "My Jamaican Guy", all directed by Jean-Paul Goude. |

| 1988 | Christmas at Pee Wee's Playhouse (TV special) | Guest performer: reinterpretation of "The Little Drummer Boy" |

| 2002 | Pavarotti & Friends 2002 for Angola | Guest performer: "Pourquoi Me Réveiller" (feat. Luciano Pavarotti) |

| 2005 | So Far So Goude | DVD only available as a bonus with the purchase of Thames & Hudson's biography on Jean-Paul Goude[144] |

| 2010 | Grace Jones – Live in NYC 1981 | Remastered version of A One Man Show with 3 bonus music videos, "Slave to the Rhythm", "Love Is the Drug" and "Crush" |

| 2012 | The Diamond Jubilee Concert (TV special) |

Guest performer: "Slave to the Rhythm" |

| Documentaries | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Title | Notes |

| 1979 | Army of Lovers or Revolution of the Perverts/ Armee der Liebenden oder Revolte der Perversen | |

| 1984 | Mode in France | |

| 1990 | Superstar: The Life and Times of Andy Warhol | |

| 1996 | In Search of Dracula with Jonathan Ross | |

| 1998 | Behind the Music – Studio 54 | |

| 2007 | Queens of Disco | |

| 2017 | Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami | |

Awards and nominations

| Year | Awards | Work | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | Billboard Music Awards | Herself | Top Disco Artist - Female | Nominated |

| 1984 | Grammy Awards | A One Man Show | Best Video Album | Nominated |

| 1985 | Bravo Otto Awards | Herself | Best Female Actress (Silver) | Won |

| Saturn Awards | Conan the Destroyer | Best Supporting Actress | Nominated | |

| 1986 | A View to a Kill | Nominated | ||

| MTV Video Music Awards | "Slave to the Rhythm" | Best Female Video | Nominated | |

| 1987 | Saturn Awards | Vamp | Best Supporting Actress | Nominated |

| 1988 | Golden Raspberry Awards | Siesta | Worst Supporting Actress | Nominated |

| 1999 | Golden Raspberry Awards[145] | "Storm" | Worst Original Song | Nominated |

| 2008 | Q Awards[146] | Herself | Q Icon | Won |

| 2009 | Helpmann Awards | Hurricane Tour | Best International Contemporary Music Concert | Nominated |

| 2014 | Rober Awards Music Poll | Nightclubbing | Best Reissue | Nominated |

| 2016 | NME Awards | I'll Never Write My Memoirs | Best Book | Nominated |

| 2017 | The Voice of a Woman Awards[147] | Herself | Lifetime Achievement Award | Won |

| Bahamas International Film Festival | Career Achievement Award | Won | ||

| 2023 | Grammy Awards[148] | Renaissance | Album of the Year (as a featured artist) | Nominated |

References

- ^ Ganatra, Shilpa (28 October 2016). "Grace Jones: 'Carry yourself with class'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

I don't spend much time in the States even though I have a place in New York and am a US citizen...

- ^ Jones, Daisy (2 August 2018). "The Guide to Getting Into Grace Jones". Retrieved 27 February 2020.

Jamaican born R&B singer Grace Jones

- ^ Gardner, Abigail (2016). 'Rock On': Women, Ageing and Popular Music. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138261419.

R&B singer Grace Jones who later branched out into disco, reggae and rock.

- ^ a b c "Grace Jones". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b Katz, Evan Ross, logo, 24 August 2015, "Grace Jones Perfects The Art Of Topless Hula-Hooping At Brooklyn's Afropunk Festival (NSFW)". Accessed 4 May 2016.

- ^ a b Prato, Greg. "Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ a b Beta, Andy (1 May 2014). "Grace Jones – Nightclubbing". Pitchfork. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Fisher, Mark (7 November 2007). "Glam's Exiled Princess: Roisin Murphy". Fact. London. Archived from the original on 10 November 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (18 January 2017). "Mark Fisher's k-punk blogs were required reading for a generation". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ Staff. "Art-Pop Before 'Art Pop'". The Style Con. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ Thornton, Andy. "Review: Grace Jones - Hurricane". NME. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ a b c "Greatest of All Time Top Dance Club Artists : Page 1". Billboard.com. December 2016.

- ^ "Grace Jones: 'Carry yourself with class'". Irishtimes.com. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Grace Jones Bio - Grace Jones Career". Mtv.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014.

- ^ Our Movie Houses: A History of Film & Cinematic Innovation in Central New York. Norman O. Keim. 9 June 2008. p. 114. ISBN 9780815608967.

- ^ "Grace Jones Facts, information and pictures". Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ "Grace Jones' mother passes". 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Marjorie Jones, Mother of Actress Grace Jones and Bishop Noel Jones, Dies at 90". 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Memorial for Bishop Robert W. Jones draws 1,000 to Oncenter". 19 May 2008.

- ^ Henley, Patricia (1999) The Hummingbird House, MacMurray: Denver.

- ^ a b "Robert Winston Jones Obituary". Syracuse.com. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "City of Refuge Church – Los Angeles Bishop Noel Jones". Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Miranda Sawyer (10 October 2008). "State of Grace". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Jones & Morley 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, pp. 17, 20.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 6.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 25.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d Sawyer, Miranda (11 October 2008). "State of Grace: Miranda Sawyer Meets Grace Jones". The Observer. London. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 24.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 43.

- ^ Brown, Helen (4 November 2008). "Grace Jones at 60". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 40.

- ^ a b Jones & Morley 2015, p. 45.

- ^ a b c "Jones the Exotic May Day". The Afro-American. 8 June 1985. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, pp. 58–64.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 68.

- ^ Lopez, Antonio (2012). Antonio Lopez: Fashion, Art, Sex, and Disco. Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0847837922.

- ^ Kershaw, Miriam (1997). "Performance Art". Art Journal. 56 (Performance Art): 19–25. doi:10.2307/777716. JSTOR 777716.

- ^ "Grace Jones". Fashion Insider: Supermodels Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Grace Jones – Portfolio (Vinyl, LP, Album) at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "La storia di Stryx, il programma musicale più geniale mai prodotto dalla Rai". Rockit.it. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Stryx era tutto quello che la televisione italiana non è mai stata". Vice.com. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Stryx/ Video, il varietà Rai del 1978 è diventato un "cult" all'estero: ecco cos'era". Ilsussidiario.net. 5 December 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "The World of Grace Jones". Theworldofgracejones.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ "The World of Grace Jones". Theworldofgracejones.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Joey Michaels. "3349. "Breakdown" by Grace Jones". Sadclownrep.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Pull Up to the Bumper by Grace Jones Songfacts". Songfacts.com. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Allen, Jeremy. "Grace Jones – 10 of the best". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...NME End of Year Lists 1981..." Rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Best Albums of the 1980s". Slantmagazine.com. 5 March 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "3333. "Walking in the Rain" by Grace Jones". Sadclownrep.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ "Jones slap tops TV chat show poll". BBC News. 22 January 2006. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Paul Flynn. "The Apple Stretching Dummy » Reviews". Dummymag.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ Michael Verity. "Awesome Album Covers: Grace Jones' "Living My Life"". Wnew.radio.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ Jones, Grace. "Grammy Awards (1984)". IMDb.com.

- ^ "LOU REED, MILES DAVIS AND GRACE JONES SELLING HONDA SCOOTERS AND TDK TAPE IN THE 1980S". Dangerousminds.net. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Amazing Grace: she battles bond, rocks with "rocky iv" hunk dolph lundgren-- have you met miss jones?". Dolph: The Ultimate Guide. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Perfect Songs artists/writers Trevor Horn". perfectsongs.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Billboard – Google Livros. 22 November 1986. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ Billboard – Google Livros. 13 December 1986. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ "Li: Island Life". Library of Inspiration.

- ^ Will Hodgkinson. "Snapshot: Grace Jones". London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ^ "How to Fake a Grace Jones Cover". Flavorwire.com. 24 February 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Images: Grace Jones by Jean-Paul Goude". Afirstclassriot.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Nicki Minaj Channels Beyoncé, Grace Jones, and Gaga in "Stupid Hoe"". Thenynthlife.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ "Nile & Bernard - Chic - Tribute @ Disco-Disco.com". Disco-disco.com. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, pp. 231–233.

- ^ "Grace Jones – Volunteer (Rare demo)". 13 September 2009. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (29 April 2021). "Grace Jones' 20 greatest songs - ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Walters, Barry (25 August 2015). "As Much As I Can, As Black As I Am: The Queer History of Grace Jones". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

Even Moulton buried the hatchet for a 1997 house remake of Candi Staton's "Victim", but Island nixed its release on conceptual grounds: They thought Grace Jones couldn't be a victim of anything.

- ^ "Sci-Fi Channel Launch Vampire Film Season with Worldwide Exclusive – A New Song from Grace Jones". Prnewswire.co.uk. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ^ "Grace Jones". Montrealmirror.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ "Grace Jones – Hurricane (Vinyl) at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 30 August 2008.

- ^ "Grace Jones & Tricky – Clandestine Affair". Discogs.com. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ "The Notorious K I M by Lil Kim @ ARTISTdirect.com – Shop, Listen, Download". Artistdirect.com. 27 June 2000. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ Alexis Petridis (13 November 2004). "Produced by Trevor Horn, Wembley Arena, London". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ "BBC – Collective – Produced by Trevor Horn". BBC Online. 21 November 2004. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Michael Osborn (26 November 2008). "An audience with Grace Jones". BBC News Online. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Simon Hattenstone (17 April 2010). "Grace Jones: 'God I'm scary. I'm scaring myself' – Music – The Guardian". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Frank Veldkamp (2009). "aulo Goude Son of a Hurricane". Missgracejones.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013.

- ^ Lars Brandle. "'Hurricane' Jones Blows Through This October". Billboard.biz. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ "Hurricane Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More". Metacritic.com. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Colin Paterson (20 June 2008). "Grace Jones performs at Meltdown". BBC News Online. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Sam Jones (21 April 2008). "Meltdown moves from trip-hop to sci-fi with style". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- ^ "nick hooker". Nickhooker.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ "Grace Jones photoshoot for Dazed and Confused". Dazeddigital.com. 16 October 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ "Grace Jones to Perform at 18th Annual Elton John AIDS Foundation Academy Awards Viewing Party" (Press release). Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ "$3.7 Million Raised at Elton John AIDS Foundation Oscar Party". 8 March 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Curtain rises on Congress". Fifa.com. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- ^ "Sharon Stone, Deborah Harry, Grace Jones, Bebel Gilberto help to Raise $1.3 Million for amfAR in Brazil". Amfar.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Ladies and Gentlemen – Miss Grace Jones". Vada Magazine. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ Stingley, Mick (29 October 2012). "Grace Jones Brings Fierceness, High Fashion to Pre-Hurricane New York City: Concert Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Singh, Anita (5 September 2012). "GQ Men of the Year Awards: highlights and lowlights". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (21 October 2014). "Kanye West, Chvrches, Bat For Lashes, Haim, Pusha T, Charli XCX Appear on Lorde's The Hunger Games: Mockingjay, Pt. 1 Soundtrack". Pitchfork. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Schiller, Rebecca (30 June 2015). "Grace Jones reveals details of 'I'll Never Write My Memoirs' |". Gigwise.com. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Humanz: CD". Gorillaz.com. 23 March 2017. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ "Grace Jones ready for national award Archived 21 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine", Jamaica Observer, 14 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018

- ^ "Grace Jones' Meltdown | Southbank Centre". Southbankcentre.co.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "Watch Grace Jones debut new songs at Meltdown Festival". nme.com. 14 June 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Sam Moore (9 April 2021). "Grace Jones' Meltdown Festival rescheduled to 2022". NME. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Grace Jones live at Meltdown Festival: brilliant, unbridled chaos from one of the greats". nme.com. 20 June 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Yeates, Cydney (8 September 2022). "Grace Jones had one rule for Beyonce in order to make Renaissance collab happen". Metro. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Krol, Charlotte (14 November 2022). "Primal Scream, Grace Jones, The Kooks, Human League and more for Camp Bestival 2023 twin sites line-up". NME. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Camp Bestival Dorset: Grace Jones and Craig David among headliners". BBC. 15 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Bluedot Festival 2023 Lineup". discoverthebluedot. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Bluedot festival: who is headlining Manchester festival with Grace Jones, tickets, prices". nationalworld. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ a b Wessang, Adeline (2 April 2012). "Jean-Paul Goude Is Still Ahead of His Time". Vice. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Hall, Jake (21 April 2016). "exploring the complicated relationship between jean-paul goude and grace jones". i-D. Vice Media. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Gardner, 2012. p. 88

- ^ Molloy, Ally (2010). A–Z of the 80s. London: John Blake Publishing. p. 134.

- ^ O'Brien, Lucy (1991). Annie Lennox. London: Sidgwick & Jackson.

- ^ Julie Naughton and Pete Born (20 May 2014). "Lorde on Influences – and Cosmetics". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Interviews, Clash Magazine Music News, Reviews &; Admin (22 June 2010). "10 Things You Never Knew About... Grace Jones". Clash Magazine Music News, Reviews & Interviews. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Exploring the pioneering career and legacy of Grace Jones". faroutmagazine.co.uk. 18 May 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Dressedmen.com (24 January 2012). "Old: Music: Nicki Minaj Channels Grace Jones In "Stupid Hoe" Music Video". Old. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Amazing Grace Nile Rodgers". Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Cartner-Morley, Jess; Mirren, Helen; Huffington, Arianna; Amos, Valerie (28 March 2013). "The 50 best-dressed over 50s". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Munzenrieder, Kyle (26 October 2017). "See Grace Jones Wearing a Shrub-like Hat on the Red Carpet". Wmagazine.com. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ a b Furman, Anna (7 November 2016). "The Stories Behind the Photos on 6 Iconic Album Covers". Pitchfork. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ a b Schwiegershausen, Erica (13 November 2014). "So, Was That Kim Kardashian Cover Photoshopped?". New York. New York Media, LLC. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Pink Grace Jones by Andy Warhol". Curiator. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b "The time Grace Jones was Andy Warhol's wedding date - Interview Magazine". Interview Magazine. 1 February 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Tate. "'Grace Jones', painted by Keith Haring. Photo by Robert Mapplethorpe, 1984 | Tate". Tate.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "Richard Bernstein, 1939–2002". The Observer. 4 November 2002. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "When Keith Haring Painted the Heavenly Body of Grace Jones". Dangerous Minds. 30 January 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Grace Before Jones: Black Image-Making and the Gaze". ocula.com. 18 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Jones, Daisy (2 August 2018). "The Guide to Getting Into Grace Jones". Vice. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Doran, John (2010). "Grace Clubbing - Nightclubbing review". BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ a b "10 Things You Never Knew About... Grace Jones". Clashmusic.com. 22 June 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 14.

- ^ Jones & Morley 2015, p. 41.

- ^ Miranda Sawyer. "State of Grace: Miranda Sawyer meets Grace Jones". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Leather-bound disco queen Grace Jones and her Swedish squeeze". People. 18 July 1983. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Chafetz, Gary S. (September 2008). The Perfect Villain: John McCain and the Demonization of Lobbyist Jack Abramoff. Martin and Lawrence Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-9773898-8-9. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Willman, Chris (11 February 1990). "Queen of Pop Shock Struts into the '90s: Before Madonna and Annie Lennox, Grace Jones paved the way. Now the multi-media artist sets her sights on 'softer'". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ "Preachers Of L.A. Bishop Noel Jones Talks About Famous Sister Grace". Realitytea.com. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Paulo Goude: Son of a Hurricane". Frank Veldkamp. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Goude, Jean-Paul (2005). So Far So Goude. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500512401. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "1998 RAZZIE? Nominees & "Winners" - the Official RAZZIE? Forum". Razzies.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Q Awards 2008: The Winners". Entertainment.ie. 7 October 2008.

- ^ Bryan, Maureen A. (7 February 2018), "Grace Jones Receives The Voices of a Woman Award", VOW.

- ^ "2023 GRAMMY Nominations: See The Complete Winners & Nominees List (Updating Live)". www.grammy.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

Bibliography

- Jones, Grace; Morley, Paul (2015). I'll Never Write My Memoirs. London: Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 978-1471135217.

External links

- Grace Jones

- 1948 births

- 20th-century Jamaican women singers

- 21st-century Jamaican women singers

- Art pop musicians

- Contraltos

- Disco musicians

- Women new wave singers

- French-language singers

- Island Records artists

- Jamaican autobiographers

- Jamaican expatriates in the United Kingdom

- Jamaican emigrants to the United States

- Jamaican female models

- Jamaican film actresses

- Jamaican reggae musicians

- Jamaican television actresses

- American musicians of Jamaican descent

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Living people

- Masked musicians

- Onondaga Community College alumni

- People from Saint Catherine Parish

- Rhythm and blues singers

- Women in electronic music

- ZTT Records artists

- Post-disco musicians

- Androgynous people

- Members of the Order of Jamaica