José Luis Cuevas

José Luis Cuevas | |

|---|---|

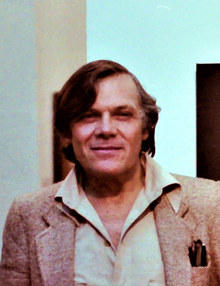

Luis Cuevas in 2011 | |

| Born | February 26, 1934 Mexico City, Mexico |

| Died | July 3, 2017 (aged 83) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Occupation(s) | painter, illustrator, printmaker, sculptor, writer |

| Movement | Modernism, Neo-figurativism, Mexican muralism |

| Awards | National Prize for Arts and Sciences of Fine Arts (1981) |

| Website | Official website |

José Luis Cuevas (February 26, 1934 – July 3, 2017) was a Mexican artist, he often worked as a painter, writer, draftsman, engraver, illustrator, and printmaker. Cuevas was one of the first to challenge the then dominant Mexican muralism movement as a prominent member of the Generación de la Ruptura (English: Breakaway Generation). He was a mostly self-taught artist, whose styles and influences are moored to the darker side of life, often depicting distorted figures and the debasement of humanity. He had remained a controversial figure throughout his career, not only for his often shocking images, but also for his opposition to writers and artists who he feels participate in corruption or create only for money. In 1992, the José Luis Cuevas Museum was opened in the historic center of Mexico City holding most of his work and his personal art collection. His grandson Alexis de Chaunac is a contemporary artist.[1]

Biography

[edit]Childhood

[edit]José Luis Cuevas was born on February 26, 1934, to a middle-class family in Mexico City. He was born on the upper floor of the paper and pencil factory belonging to his paternal grandfather, Adalberto Cuevas.[2][3]

When he was ten years old, he began studies at the National School of Painting and Sculpture "La Esmeralda", and he also started to illustrate newspapers and books.[3] However, he was forced to abandon his studies in 1946 when he contracted rheumatic fever. The illness left him bedridden for two years. During this time, he learned engraving work taught by Lola Cueto of Mexico City College.[3]

Early career

[edit]At age fourteen, he rented a space on Donceles street to use as a studio instead of returning to school as his poor health meant that did not know how long he might live. He decided it would be better to dedicate himself to his art. Cuevas learned how to horse back ride and basket weave for money. He worked on illustrations for The News,[4] and despite his lack of formal training, he taught art history classes at Coronet Hall Institute.[2] One element of his training was the opportunity to visit the La Castaneda mental hospital where his brother worked to draw the patients.[5]

Generación de la Ruptura

[edit]Cuevas was sometimes described as vain, a pathological liar and a hypochondriac, obsessed with sickness and death, especially his own.[4] Writer René Avilés Fabila once said that “The greatest love of José Luis Cuevas is named José Luis Cuevas, because he is an artist more in love with himself than with his work.” The reason for this quote is that he has done so many self-portraits that it is like having a large number of mirrors.[6] Cuevas stated that he did not believe that he was vain and says that idea started in 1955 when he decided to take a picture of himself every day, which he continued to do up to the end of his life.[4] He was one of the most photographed contemporary artists of Mexico.[7] One ludicrous story states that he visited a “vampire brothel” where they scratch and paw at customers.[citation needed] Other story relates him to a 70-year-old woman named Gloria who he tried to seduce and another one that Marlene Dietrich threw herself at him.[4] He admitted to being a bit paranoid and defensive, concerned about being cast in a negative light.[citation needed] He claimed Julio Scherer García as an enemy for interfering with his writing career. He also had feuds with painter Rufino Tamayo.[4] He claimed that José Chávez Morado, Guillermo González Camarena and the "Frente Popular de Artes Plasticas" were envious of him and that they accused him of working with the CIA in the 1950s when he was coming out after mainstream artists.[4] Even in his final years, he made deferences by opening his museum to all of his friends but those he considers enemies were not permitted inside.[8]

In the 1960s, he went to Morocco to study Islamic art, meeting painter Francis Bacon in Tangiers.[2] He became an atheist after the death of his mother in the 1970s.[4] From 1976 to 1979, he “self-exiled”, leaving Mexico for France, working on various books, serigraphs and lithographs for publication. When he returned to Mexico, he presented the exhibition “José Luis Cuevas. El regreso de otro hijo pródigo.” (José Luis Cuevas. The return of another prodigal son).[2][4]

Despite his predictions that he would live to over a hundred because various tarot readings had told him so,[9] Cuevas died on July 3, 2017, in Mexico City at the age of 83.[10][11][12]

Marriage

[edit]

Cuevas married his first wife, Bertha Riestra, in 1961.[2] He met Bertha at the La Castaneda hospital while she was there doing community service and painting. Her parents did not attend the wedding as they did not approve of him since he was an artist.[4] Despite being married, he gained a reputation as a womanizer, nicknamed “gato macho” (male cat) or seducer of women, which he took advantage of to promote himself.[4] In a Mexico City newspaper column written by him, he claimed he had over 650 erotic encounters.[4] He states that Bertha was not allowed the same freedom and that she never knew about his affairs despite his writings about them.[4] He and Bertha had three daughters, Mariana, Ximena and María Jose.[13] In 2000, Berta Riestra, his wife and, at the time, the director of the José Luis Cuevas Museum, died due to breast cancer and leukemia. The following year, he met Beatriz del Carmen Bazán, whom he married in 2003 at the museum.[2][4]

Cuevas and his wife both lived in the San Ángel neighborhood of Mexico City. The house was built for Cuevas in the 1970s by architects Abraham Zabludovsky and Teodoro González de León in a style reminiscent of Luis Barragán. The walls are tones of gray with very straight lines. The interior is minimalist with paintings by the artist on the walls and wood furniture with Mexican textiles. While the house is clean and orderly, the space dedicated as his studio is messy, strewn with books, old machinery, a telescope, mirrors, many photographs and more.[7]

Exhibitions

[edit]

Within a career that spanned over seventy years, Cuevas was a painter, writer, draftsman, engraver, illustrator and printmaker.[3][5][14] There have been solo exhibitions od Cuevas' work in museums and galleries throughout the world.[15] His first exhibition was when he was only fourteen at the Seminario Axiologico but no one came, the works came off the walls and were stepped on.[3][4] His first successful individual exhibition was at Mexico City's Galería Prisse in 1953, when he was nineteen.[2][3] In 1954, he meets the critic Jose Gomez-Sicre who invites him to exhibit at the Panamerican Union in Washington, DC.[2] This, his first U.S. exhibition, sold out opening night and resulted in interviews with Time and the Washington Post, which called him a “golden boy,” opening doors and helping to sell his paintings.[4] In 1955, he participated in the first Salón de Arte Libre organized by Galería Proteo, where he met David Alfaro Siqueiros. During the rest of the 1950s, he exhibited in Havana, Caracas, Lima and Buenos Aires, where he met Jorge Luis Borges.[2]

In the 1960 he exhibited at the David Herbert Gallery, when the NY Times compared him to Picasso. In 1961, two of his works at the Galería del L’Oblisco in Rome, Los Funerales de un Dictador and La Caída de Franco caused a diplomatic conflict with Spain that asked the images to be removed. In 1962, he exhibited a series of works based on a sculpture by Tilman Riemenschneider he saw in Munich. Cuevas' other exhibitions from this period include one at the Silvan Simone Gallery in 1967.[2]

During the 1970s, he exhibited 72 self-portraits at the Centro Cultural Universitario at UNAM, and exhibited other works at the San Francisco Museum of Art, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Caracas, Phoenix Art Museum, the Musee d’Art Moderne in Paris and the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City.[2] In 1976, he had four women tattooed with original designs of his own making, so that the art “would grow old with him” This despite the fact that tattoos were illegal in Mexico at the time.[4] In 1979 Jose Luis exhibits 50 watercolors and drawings along with illustrated letters at Tasende Gallery, La Jolla, California.

In 1981, he opened the exhibit "Signs of Life" which contained a vial with his semen and an electrocardiogram taken while he was making love. He stated in the exhibition's brochure that he would impregnate any woman that asked him to do so, but the Secretaría de Gobernación made him to remove the brochure because it was then-considered as act of prostitution.[4] In 1982, fourteen galleries in Mexico City, Barcelona, Paris and others held a simultaneous exhibits of “Marzo. Mes de José Luis Cuevas” ("March. Month of Jose Luis Cuevas.") From 1984 to 1988, a series of 50 large format drawings called “Intolerance” toured universities and museums in the U.S., Canada, Mexico and Europe. These drawings were the result of Jose Tasende's gift to Cuevas of the book "The Witches' Advocate" by Gustav Henningsen.[2] In 1985 exhibits with Henry Moore and Eduardo Chillida in the exhibition Figure Space Image at Tasende Gallery, La Jolla, California. The illustrated letters he wrote to his dealer JM Tasende during his exile from Mexico are exhibited at Tasende Gallery prior to becoming part of the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In 1991 "Celebrating 25 Years with Jose Luis Cuevas" opens at Tasende Gallery, La Jolla. He created a Talavera mural which was placed at the Zona Rosa neighborhood in 1995. In 1997 he exhibits at Tasende Gallery, West Hollywood, California. In 1998, he exhibited “Retrospectiva de Dibujo y Escultura” at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. In 1999, the Pablo Picasso Foundation presented the exhibition “José Luis Cuevas. Obra Gráfica".[2]

In 2001, he donated a sculpture called “Figura Obscena” (Obscene Figure) to the city of Colima. This sculpture became the center of a scandal in 2006.[2] Other exhibitions from the 2000s include in 2005 "Jose Luis Cuevas in Drawing and Sculpture" at the Latin American Art Museum in Long Beach, California. "Selected Drawings and Watercolors" Tasende Gallery, West Hollywood, California. In 2006, he inaugurated the Paseo Escultórico Nezahualcóyotl with a sculpture named after his wife called “Carmen.” Retrospective Exhibition at the Museum of the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City in 2008. “Exposición Siameses 50 Años de la Plástica del Maestro José Luis Cuevas” in 2009 and 2011 and “Dibujo y Escultura” in 2010. He continued to actively exhibit his work until his death, especially in Mexico.[2]

Publications

[edit]

By the age of fourteen, Cuevas had illustrated numerous periodicals and books.[15] In 1957, he went to Philadelphia to illustrate the book The World of Kafka and Cuevas for Falcon Prest Publishers.[2] In the late 1950s, he began to write on cultural topics for the Novedades de México publication, where he referred to the then mural artists establishment such as Diego Rivera as the cortina del nopal ("Nopal Cactus Curtain") and also advocated for greater artistic freedom. This philosophy inspired the founding in 1960 of the group Nueva Presencia, which he joined for a brief time. The group promoted individual expression and figurative art reflecting the contemporary human condition.[2][15]

In the 1960s, his publications included Recollections of Childhood (1963), Cuevas-Chareton (1966), a book of lithographs made at the Tamarind Workshop in Los Angeles inspired by the Marquis de Sade and Homage to Quevedo an album of thirteen lithographs dedicated to Francisco de Quevedo.[2][5]

In 1970, he presented Crime by Cuevas at the Primera Bienal del Grabado Latinoamericano in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The lithographic series called Cuevas Comedies was published in 1972, inspired by San Francisco.[2][5] He “self-exiled” to France where he exhibited at the Modern Art Museum in Paris and the Chartres Cathedral and worked on several books, serigraphs and lithographs in works called “Cuaderno de París” and “La Renaudiere.” The first was honored at the Book Fair in Stuttgart, Germany in 1978.[2]

In 1985, he began publishing a column called “Cuevario.” In 1987 he worked with the Crónica de la Ciudad de México. He published Arte-Objeto and Animales Impuros in 1995, which was inspired by a poem by José-Miguel Ullán. In 2012 he published Cartas amorosas a Beatriz del Carmen which contains 183 cards drawn by Cuevas for his wife.[2][5]

Artistic development and influence

[edit]

As Cuevas' education was interrupted by illness, he was mostly a self-taught artist. He was part of the first generation of Mexican artists to have emerged after the Muralist movement, and a main figure of both the Generación de la Ruptura (Breakaway Generation) and Neo Figurativism, associated with writers and artists such as Carlos Fuentes, Octavio Paz and Fernando Benítez.[9][14]

Cuevas was born and raised in a country which has produced major innovators in the fine arts, and he himself became a symbol of both the continuity of this tradition as well as a permanent break with the past.[8] In particular, Cuevas was an early and very outspoken critic of the muralist movement led by the then-dominant artists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros.[16] His critiques focus on how these artists depicted Mexican social intertwine and how much their art was influenced by government propaganda through sponsorship.[3][16] His opposition to the status quo and his aggressive art style caused him trouble at times, including violent public outcry to his work, written insults, personal threats and even once having had his own house attacked with a machine-gun.[3][16] These are some of the reasons that earned him the nickname of "il enfant terrible" ("The Bad Boy") of Mexican fine arts.[14][17]

His initial opposition to the Mexican cultural status quo was with the muralists, calling them and the government that supported them the “nopal cactus curtain,” acting against newer artists and innovations.[18] His first essay against the “nopal cactus curtain,” was to be published by Excélsior but ultimately rejected by the periodical, although he later renamed and published it as “Letter to Siqueiros” in a magazine titled "Perfumes y Modas" ("Perfumes and Fashions") and dropped off a copy of the magazine at Siqueiros's house. Later, with the help of Carlos Fuentes he published in "Museo en la Cultura" ("Museum in Culture"), a supplement of Novedades newspaper, where he continued his critique towards the Mexican muralist movement. Throughout this time, he became friends with a number of other writers such as Fernando Benítez, José Emilio Pacheco, José de la Colina, Carlos Monsiváis who, along with writer Carlos Fuentes, were known as “La Maffia” a critique group of Mexico's then-current culture. It also earned him scorn and critique, especially from Leopoldo Méndez and Raúl Anguiano, as well as strong opposition from many at the Academy of San Carlos. Despite this opposition, Siqueiros wanted Cuevas to become part of the muralist group, saying that his work had an Orozco quality.[4] Since that time, the muralism tradition waned but Cuevas remaines a controversial and oppositional figure, criticizing writers and artists he felt criticized the country's corruption and other problems but at the same time were a party to them. He also stated that he was strongly against opposed to those who he felt used art for “fraudulent” ends as well as those who copied others’ work and those who sold out their art only to make money.[16]

Themes in Cuevas’ work tend to be bleak, grotesque, enveloped in anguish and fantasy, with human figures distorted to the point of uniqueness.[15][18] His work has been described as having a “great gestural ferocity” often preferring subjects relating to human degradation such as prostitution and despotism.[14] His most characteristic work involves images of disfigured creatures and the misery of the contemporary world.[5] Although he was not opposed to worldly pleasures, they are not depicted in his work. He stated that his work leans more towards the flesh in an “excessive” way with the presence of death. Cuevas said that his drawing representa the solitude and isolation of contemporary man and man's inability to communicate. He also stated that it is an “invitation to return to vegetarianism.[15][16]"

Cuevas stated that he drew a skull as he considered them devoid of expression and they are not necessarily representative of death in Mexican culture. He preferred to draw cadavers and bodies shortly after death, as they still retain the individual human qualities. In this approach, he stated that he followed elements of German Expressionism, Catalan Romanesque and Romanticism of the 19th century. He felt very “Spanish” in this as Goya used to paint cadavers as well and yet, far from José Guadalupe Posada who drew skulls and bones.[3][16] His work was influenced by Spanish poetry and Spanish cities as Seville and Barcelona have appeared in his works.[18] His predilection for the darker side of life along with breaking with tradition has meant belated acceptance for his work in certain circles of the art market.[16]

Cuevas’ influences included Goya, writer Francisco de Quevedo, Picasso, with some hues from Posada and Orozco.[3][15][18] Over the years, he paid homage to his favorite painters and writers, such as Fyodor Dostoevsky, Franz Kafka, Francisco de Quevedo and Marquis de Sade, in numerous series of drawings and prints.[15]

Cuevas's style is aggressive and lacks inhibition which often shocks the observer.[8] Cuevas's drawings, which were done in pen and ink, gouache and watercolor, are mostly done on very large sheets of paper. In many of these drawings, the figures transform into animals or acquire an animal quality.[3] Well acquainted with the cinematic arts, he manipulated data and even concocted events, drawing on his memory for plausible details.[8] His best known event of this type was the creation of the “Mural Efímero” (Ephemeral Mural), which he created and immediately destroyed publicly as a challenge to the Mexican muralism movement.[2] He gave what is now known as “Zona Rosa” its name, located in the then cosmopolitan section of Colonia Juarez, stating that "Es demasiado ingenua para ser roja, pero demasiado frívola para ser blanca, por eso es precisamente rosa" ("it's too naive to be red, but too frivolous to be white, that's why it is precisely pink.[19]")

His work reates controversy to the end and his appearance attracted large numbers of women.[17]

Recognition

[edit]Cuevas’ earliest award was in 1959, the International First Prize for Drawing at the São Paulo Biennale, with 40 works from the series Funeral of a Dictator, which was followed by First Prize at the International Black and White Exhibition in Lugano, Switzerland, in 1962.[3][15] His other awards from the 1960s include the Prize for Excellence in Art and Design at the 29th Annual Exhibition of the Art Directors’ Club, Philadelphia, United States, in 1964, Premio Madeco at the II Bienal Iberoamericana de Grabado at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Santiago, Chile, in 1965 and First International Prize for Printmaking, Triennial of Graphic Arts, New Delhi, India, 1968.[3][15]

In 1977 he won First Prize at the III Latin American Print Biennial in San Juan, Puerto Rico.[15] In 1981, he earned the National Prize of Culture, which signified his acceptance by the people of Mexico.[3] Cuevas' other honors of the 1980s included having his work exhibited at the 1982 Venice Biennial,[20][21] Premio Nacional de Arte from the Mexican government in the same year, and the International Prize from the World Council of Engraving in the United States.[2][15]

In the 1990s, he received the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from France in 1991, induction in the National System of Creators of Mexico in 1993 and In 1997 the Premio de Medallística Tomás Francisco Prieta from Queen Sofía of Spain .[2][5]

In the 2000s he received the Jerusalem Prize from the City of Jerusalem and the World Zionist Organization in 2007 and the Lorenzo the Great Prize at the VIII Biennial of Florence in 2012.[2]

In addition to awards for his artwork, Cuevas received other honors as well. These include honorary doctorates from Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa (1984), the Universidad Veracruzana (2004), the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (2007) and the Instituto Superior de Arte and the Casa de las Américas in Havana (2008). He was honored as Captain of the Yaqui Army by the leaders of the Yaqui people in 1996. In 1989, the cities of Monterrey and Tijuana declared him an “honored guest” and he received the keys to the two cities.[2]

José Luis Cuevas Museum

[edit]

In the late 1980s, Cuevas obtained the old monastery of Santa Inés in Mexico City's historical center for the purpose of creating the José Luis Cuevas Museum, which was inaugurated in 1992. The first director of the museum was his first wife, Bertha until her death in 2000. In 2005, his second wife, Beatriz del Carmen, took over operations.[2] The Museum has been backed by the Fundación Maestro José Luis Cuevas since 2003.[22] Because of the opposition in some essential artistic statements between José Luis Cuevas and some professors in the Academia de San Carlos, which is located half a block to the south, the artistic community in this art school say "el vecino de enfrente" (neighbor from across the street" to refer to the now late artist and the Museum).

The Museum's collection includes more than 1860 pieces by various artists, mostly from Latin America. The pieces are rotated among the various building's rooms. One of the main pieces is "La Giganta" ("The Giantess") by Cuevas, which is situated in the central courtyard.[23] The androgynous sculpture was created in 1991 and inspired by a poem by Baudelaire.[2][8] The museum is considered to be controversial in no small part due to the “Erotic Room," filled with Cuevas' own drawings on the theme and of actual bordellos and cabarets, and the presence of a large brass bed on which he claimed he had many sexual encounters.[8][17] The museum also contains a library with 45 large volumes with over 11,500 newspaper clippings as well as 500 books dedicated to Cuevas' work.[4]

- Gallery

References

[edit]- ^ "Se inaugura en Veracruz la exposición Mala Sangre / Bestiario de Alexis de Chaunac". vanidades.com. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab "Cronología biográfica" [Biographical chronology] (in Spanish). Mexico City: José Luis Cuevas Museum. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Jose Luis Cuevas". San José State University Digital Art Lobby. Archived from the original on December 1, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Cherem S, Silvia (May 28, 2000). "Entrevista/ Jose Luis Cuevas/ El ombligo de Cuevas" [Interview/Jose Luis Cuevas/The navel of Cuevas]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Obra temprana, de José Luis Cuevas, en la "Ramón Alva de la Canal"" [Obra temprana by Jose Luis Cuevas at the "Ramon Alva de la Canal"] (in Spanish). Mexico: Universidad Veracruzana. Retrieved June 2, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Sanchez, Leticia (May 23, 1997). "Jose Luis Cuevas, enamorado de si mismo" [Jose Luis Cuevas, in love with himself]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- ^ a b Toledo, Fernando (December 21, 1995). "Jose Luis Cuevas: En la cueva de Cuevas" [Jose Luis Cuevas: In the cave of Cuevas]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Taibo I, Pace Ignacio (September 1994). "The Museo Jose Luis Cuevas". Americas. 46 (5): 50.

- ^ a b "José Luis Cuevas festeja 78 años de vida" [José Luis Cuevas celebrates 78 years of life]. El Financiero (in Spanish). Mexico City. February 26, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ DAVID MARCIAL PÉREZ (4 July 2017). "Muere el artista mexicano José Luis Cuevas". El Paīs (in Spanish).

- ^ Alberto Nájar (4 July 2017). "Muere el artista plástico mexicano José Luis Cuevas, el líder de la "Generación de la Ruptura"" (in Spanish). BBC Mundo.

- ^ "Mexican painter Jose Luis Cuevas dies at 83". ABC News. 3 July 2017.

- ^ Gutiérrez, Laura G. (14 December 2010). "Reframing the Retablo : Mexican Feminist Critical Practice in Ximena Cuevas' Corazon Sangrante". Feminist Media Studies. 1 (1): 73–90. doi:10.1080/14680770120042873. S2CID 144861467.

- ^ a b c d "Rendirán homenaje al artista plástico José Luis Cuevas" [Will render homage to fine artista José Luis Cuevas]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. February 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "José Luis Cuevas biography". Ro Gallery. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rodriguez, Juan (September 15, 1995). "Jose Luis Cuevas: un viaje hacia el interior" [Jose Luis Cuevas: a voyage to the interior]. La Opinión (in Spanish). Los Angeles. p. 8E.

- ^ a b c "Museo José Luis Cuevas". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Ruiz, Blanca (April 27, 2001). "Travesias/ Jose Luis Cuevas". Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 37.

- ^ "La Zona Rosa cada vez más 'roja'" [Zona Rosa getting more "red"]. Terra (in Spanish). Mexico City. Agencia CFE. August 20, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ^ "José Luis Cuevas | artnet". www.artnet.com.

- ^ Travels in the Labyrinth: Mexican Art in the Pollak Collection. 2001-01-12. ISBN 0812217748.

- ^ "Fundación Maestro José Luis Cuevas Novelo, A.C." (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ "Colección permanente del Museo" [Permanent collection of the museum] (in Spanish). Mexico City: José Luis Cuevas Museum. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to José Luis Cuevas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to José Luis Cuevas at Wikimedia Commons

- 1934 births

- 2017 deaths

- 20th-century Mexican painters

- Mexican male painters

- 21st-century Mexican painters

- Mexican printmakers

- Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado "La Esmeralda" alumni

- Artists from Mexico City

- Writers from Mexico City

- 20th-century Mexican male artists

- 21st-century Mexican male artists