Death of Cooper Harris

| |

| Date | June 18, 2014 |

|---|---|

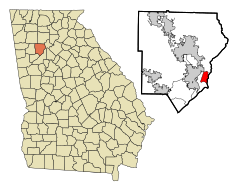

| Location | Vinings, Georgia, U.S. |

| Type | Hot car death, child death, sexual exploitation of children, child sexting |

| Deaths | Cooper Harris |

| Accused | Justin Ross Harris |

| Charges |

(Charges dropped in 2023)

|

| Trial | October 3 – November 14, 2016 |

| Verdict |

(Overturned in 2022)

|

| Sentence |

|

Cooper Harris was a 22-month-old toddler who died of hyperthermia on June 18, 2014, in Vinings, Georgia. His father, Justin Ross Harris ("Ross"), had left him strapped in the rear-facing car seat of his SUV, where the toddler remained for approximately seven hours.[1] Ross was arrested and charged with his son's death, which he called a tragic accident.[2] After a jury trial that garnered national media attention, he was found guilty of malice murder and felony murder, among other charges, on November 14, 2016.[3][4] He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole plus 32 years.[5][6] In 2021, the Harris case was the subject of a documentary, Fatal Distraction.[7]

On June 22, 2022, Ross's convictions of murder and cruelty relating to his son, Cooper Harris, were overturned by the Georgia Supreme Court, which concluded that he had not received a fair trial.[8][9][10] Ross remained convicted of felony attempt to commit sexual exploitation of children and dissemination of harmful material to minors.[11][12] In May 2023, prosecutors announced that he would not be retried on the murder and cruelty charges.[13]

Justin Ross Harris

[edit]Justin Ross Harris | |

|---|---|

| Born | November 27, 1980 |

| Education | University of Alabama |

| Occupation | Web developer |

| Employer | The Home Depot (2012–2014) |

| Spouse |

Leanna Taylor

(m. 2006; div. 2016) |

| Children | 1 (Cooper Harris, died 2014) |

| Conviction(s) |

(Charges dropped in 2023)

|

| Criminal penalty |

|

Date apprehended | June 18, 2014 |

| Imprisoned at | Macon State Prison Released June 2024 |

Ross was born in 1980. He briefly worked as a police dispatcher in Tuscaloosa until 2009, according to police spokesman Sergeant Brent Blankley.[14] He graduated from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa in 2012, receiving a bachelor's degree in commerce and business administration.[14] Ross then moved to Georgia to work for The Home Depot as a web developer.[15]

Incident

[edit]On the morning of June 18, 2014, Ross was to take his son, Cooper, to daycare on his way to work. At around 8:57 a.m., he and Cooper ate breakfast at a Chick-fil-A restaurant less than a mile from his office on Cumberland Parkway, near its intersection with Paces Ferry Road in Vinings, Georgia. Ross then drove his SUV to the Home Depot office where he worked, with Cooper strapped in a rear-facing car seat in the back. He entered the office at 9:25 a.m., leaving Cooper in the car seat.[16]

At or around 12:30 p.m., Ross was picked up from work by two friends to have lunch at a nearby Publix. Following lunch, they proceeded to a nearby Home Depot located on Cumberland Parkway, where Ross purchased light bulbs. After his friends dropped him off at his workplace parking lot, he walked to his SUV, opened the driver's side door, and placed the bulbs inside.[16][6][17]

At 4:16 p.m., approximately seven hours after initially leaving Cooper in the SUV, Ross returned to the vehicle and drove it away from his office. He had planned to visit an AMC movie theater to see 22 Jump Street with friends after work. After driving for a few minutes, Ross pulled into a shopping center parking lot, where witnesses reported hearing "squealing tires"[18] and a man screaming, "What have I done?"[16] Ross briefly tried to perform CPR on Cooper before a bystander took over, while other bystanders called 911.[2][5] Police and firefighters that had been patrolling nearby arrived within seconds of the call; Ross was detained and, when questioned, told police he forgot that Cooper was still in his car seat.[16]

Temperatures that day had reached 92 °F (33 °C).[19] The police estimated that Cooper likely died around noon, two and a half hours after Ross had left him in the car.[16][20]

Investigation

[edit]The investigation into the death of Cooper Harris focused heavily on his father's extramarital sexual affairs, which was later identified as a significant procedural error.[21] On the day of Cooper's death, Ross had been sending and receiving sexually explicit texts (some with nude images) in conversations with six persons, including one under the age of consent.[19] Detectives also later said that they found Ross's responses during his interrogation to be unusual—one reported hearing Ross say "I can't believe this is happening to me" and "I'll be charged with a felony."[19]

Criminal trial

[edit]Prosecutors charged Ross with malice murder, felony murder, cruelty to children, sexual exploitation of children, and dissemination of harmful materials to minors.[22] A jury in Glynn County spent about a month listening to evidence in the case and deliberated for four days before convicting Ross on all counts.[23]

Jury selection and venue

[edit]The trial was initially held in Cobb County, Georgia. After nearly three weeks of jury selection, Superior Court Judge Mary Staley Clark, granted a defense motion for a change of venue, and the trial was moved to Brunswick in Glynn County.[24] Staley determined that the local media attention had impacted the Cobb County's prospective jurors.[25]

Evidence

[edit]As to Cooper Harris's death, prosecutors contended that Ross had intentionally left Cooper in the car in order to pursue extramarital sexual relationships.[13] The defense, led by Maddox Kilgore, said that Ross had forgotten Cooper in the car as a consequence of his daily routine having been altered in several ways.[26] In total, the prosecution's case in chief included 51 witnesses, while the defense called 18 witnesses.[27]

Several prosecution witnesses testified to Ross's behavior on the scene. Brett Gallimore, a police officer, testified that he did not observe Ross cry, that he felt Ross was feigning grief, and that Ross cursed at him.[28] On cross examination, Gallimore was asked why he said Ross was "acting hysterical and extremely upset" in his initial report;[29] Gallimore said that he deliberately used the word "acting" to indicate that Ross was not being genuine.[30] One witness testified that he took over performing CPR after he observed that Ross was "fumbling around" and improperly performing CPR, though the witness said he knew Cooper was dead, comparing his attempts at breath support to "blowing into a busted bag".[31] Police officer Jacqueline Piper said she thought it was unusual that Ross was not near his son when she arrived on scene.[32]

Detective Phil Stoddard's testimony became particularly contentious.[33] Stoddard testified with video evidence that Ross had failed to report his lightbulbs purchase and his placement of those lightbulbs in his SUV.[34] Stoddard also said that Ross must have seen Cooper when he dropped the light bulbs into the car because Ross had placed his head in the car while doing so.[35] But security tapes played for the jury[36] showed that Ross never put his head in the car and that his eye line remained above the car's roof.[35] On cross examination, Stoddard partially retreated from statements he made at a pretrial hearing[27]—that Ross had conducted internet searches into child-free lifestyles, visited a child-free website, and searched for a video on the danger of leaving animals in cars.[33] He said that Ross had not searched for the animal video and that he had instead seen the video on Reddit's homepage,[37] and he agreed that another prosecution witness—a friend of Ross's—had sent Ross the child-free website "as a joke".[38] Prosecution witness Roy Yeager, a detective, testified that he had not found any such internet searches when he examined the cellphones and computers owned by Ross and his then-wife.[39]

As to Ross's alleged motive, five women, including one minor, testified as to Ross's interactions with them.[27] The prosecution presented a text Ross sent minutes before leaving Cooper in the car that stated, "I love my son and all, but we both need escapes."[40] The state's evidence also included nine enlarged photographs of Ross's penis.[41] For the defense, Leanna Taylor (Cooper's mother, who had, by this point, divorced Ross[42]), testified that Ross would not have intentionally killed their son.[43] On cross examination, the prosecution suggested that, in the aftermath of Cooper's death, Taylor had been principally concerned with her future with Ross; on redirect, Taylor said, "[Ross] destroyed my life. I'm humiliated. I may never trust anybody again. If I never see him again after this day, that's fine."[27] Testifying for Ross, a travel agent said that Ross had contacted her about a family vacation the day before Cooper's death.[44] The defense also called several character witnesses, who generally testified that Ross was a loving father, although the prosecution pressed these witnesses on the fact that they did not know about his extramarital affairs.[45]

Dr. Gene Brewer, a psychology professor[46] and memory and attention expert, testified for the defense that it was "absolutely possible" that Ross had left Cooper in the car as a result of a memory lapse,[27] and that there was "nothing unique about this case as relative to the other cases where this has happened".[46] On cross examination, Brewer said that he was not aware of other cases in which a parent had texted "I need an escape. I love my son and all but we both need an escape" ten minutes prior to leaving a child in a car.[27]

Verdict and post-conviction motion

[edit]A jury found Ross guilty of all counts on November 14, 2016.[16] He was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole plus 32 years.[6]

In January 2017, Ross's legal team filed a motion for a new trial with the trial court, arguing that prejudicial testimony (revelations of Ross's numerous affairs, and self-admitted sex addiction) "made it an absolute impossibility" for Ross to have received a fair trial;[47] Clark denied the motion on May 20, 2021.[48]

Appeal and dismissal of charges of murder and cruelty

[edit]On January 18, 2022, the Supreme Court of Georgia, heard arguments for a new trial by Ross's lawyer Mitch Durham,[49] who argued that the extensive evidence presented as to Ross's affairs and sex life[13] were nonprobative and prejudicial.[50] On June 22, 2022, in a 6–3 decision, the court agreed, finding that the evidence regarding Ross's sexual activities was "needlessly cumulative and prejudicial"[21][51]: 3 and reversing the convictions on the murder and cruelty counts.[52][53][54] The court's majority opinion said that the state had introduced "a substantial amount of evidence to lead the jury to answer a ... legally problematic question: what kind of man is [Ross]?"[55] It held that the case should have been severed, such that there would have been separate trials for sex-crime charges and murder/cruelty charges.[15][51]: 101–02 A dissenting opinion said that the state was "entitled to introduce, in detail, evidence of the nature, scope, and extent of the truly sinister motive it ascribed to [Ross]".[52]

On May 25, 2023, the murder and cruelty charges against Ross were dismissed. The convictions of felony attempt to commit sexual exploitation of children and dissemination of harmful material to minors remained.[12][11][55] In a statement, Cobb County District Attorney Flynn Brody said that, after an eleven-month review, it determined that the Georgia Supreme Court's decision would prevent it from relying on "[c]rucial motive evidence", and, in light of that restriction, it had decided it would not retry Ross on the murder and cruelty charges.[56] Ross's attorneys responded to the dismissal by characterizing it as a confirmation of Ross's innocence and disputing whether prosecution of parents such as Ross deters unintentional deaths, saying, "Charging a grieving parent for an unintentional memory failure does nothing to prevent the tragedy from happening to another. In fact, child fatalities from hot cars increased after Ross'[s] 2016 trial, the most widely reported hot car death case in history."[56]

In 2024, District Attorney Brody lost re-election as an incumbent to Sonya Allen. Allen ran on a platform of denial of justice to Cobb County, citing the handling of the Harris murder case.

In June 2024, Justin Ross Harris was released from prison.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Robinson, Carol (June 19, 2014). "Tuscaloosa man charged with murder in Georgia after leaving toddler son in sweltering SUV for 7 hours". AL.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Pearson, Michael (June 27, 2014). "5 key questions about Georgia toddler's hot-car death". CNN. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ Lance, Natisha (November 21, 2020). "'Fatal Distraction': Ross Harris documentary claims untold story about convicted father". 11Alive.

- ^ "Justin Ross Harris' ex-wife Leanna Taylor still believes son's hot car death was a tragic accident". ABC News. February 16, 2017. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "Georgia dad Justin Harris convicted of murder in son's hot car death". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ a b c Boone, Christian (December 5, 2016). "Justin Ross Harris sentenced to life in prison without parole". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ Bugbee, Teo (December 8, 2021). "'Fatal Distraction' Review: Parents Go Through the Unthinkable". New York Times.

- ^ "Georgia Supreme Court overturns Justin Ross Harris' murder conviction in his son's hot-car death". CNN. June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "Georgia Supreme Court overturns murder conviction against Justin Ross Harris, whose son died after being left in a hot car for hours". CBS News. June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "Justin Ross Harris, Georgia man convicted in baby son's hot car death, has verdict overturned". Fox News. June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Aldridge, Donesha (May 25, 2023). "Attorney: Ross Harris numb from emotions but relieved DA's office won't re-try murder case in son's hot car death". 11alive.com. WXIA-TV. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ a b Associated, Press (May 26, 2023). "Georgia father won't face a retrial over murder charges in child's hot car death". nbcnews.com. NBC News / Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c Levenson, Michael (May 25, 2023). "Prosecutors Won't Retry Father Whose Son Died in Hot Car". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Karimi, Faith; Pearson, Michael (January 6, 2015). "Georgia toddler death: Who is Justin Ross Harris?". CNN. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Parker, Wendy (May 25, 2023). "Cobb won't retry Justin Ross Harris in son's 'hot car' death". East Cobb News. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Boone, Christian (July 3, 2014). "Timeline of toddler's death". MyAJC. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ Boone, Christian; Rankin, Bill (November 15, 2016). "Why did the jury convict Justin Ross Harris on all counts?". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ McCoy, Terrence (July 16, 2014). "The media trial of Leanna Harris, charged with nothing in hot-car death of her son". Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c Eliott C. McLaughlin; Dana Ford (July 3, 2014). "Police: Dad was 'sexting' as son was dying in hot car". CNN. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ Boone, Christian (September 3, 2019). "Five years later, Cobb hot car death saga still haunts". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Johnson, Larry Felton (June 22, 2022). "Georgia Supreme Court Overturns Ross Harris Conviction For The Hot Car Death Of His Son; Cobb DA To File Motion For Reconsideration". Cobb County Courier. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Burke, Minyvonne (June 22, 2022). "Affairs shouldn't have been a factor in Georgia hot car murder case, judge says in overturning dad's conviction". NBC News. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ King, Michael (November 14, 2016). "Dad found guilty in hot-car death of son". WXIA-TV. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2023 – via USA Today.

- ^ Reed, Kristen; Wolfe, Julie (June 16, 2016). "New venue for Ross Harris hot car death trial named". 11 Alive.

- ^ "5 things to know about the new Justin Ross Harris trial". Atlanta Journal Constitution. September 9, 2016. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Boone, Christian; Rankin, Bill (December 14, 2020). "Ross Harris defense reveals frustrations with judge in hearing for new trial". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Cuevas, Mayra (November 4, 2016). "Day by day: Key moments from the Justin Ross Harris trial". CNN. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Boone, Christian (October 5, 2016). "Officer's testimony leads defense to seek a mistrial". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Halicks, Richard (October 5, 2016). "Minute by minute in the Ross Harris murder trial, Day 3". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Blitzer, Ronn (November 14, 2016). "Now That Justin Ross Harris has Been Convicted, Get Ready for the Appeal". Law & Crime. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Rankin, Bill (October 4, 2016). "Emotional witness describes trying to revive little Cooper Harris". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Williams, Misty (October 4, 2016). "Minute by minute in the Justin Ross Harris trial". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Boone, Christian (October 25, 2016). "Detective spars with Ross Harris attorney in revealing cross-exam". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Boone, Christian; Rankin, Bill (November 14, 2016). "Why did the jury convict Justin Ross Harris on all counts?". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Rankin, Bill; Schneider, Craig; Torpy, Bill (July 21, 2014). "Did Police Exaggerate Account of Child's Death in Hot Car?". Boston.com. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Boone, Christian; Rankin, Bill (November 10, 2016). "The Ross Harris trial: What the jury is thinking about". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Rankin, Bill (October 25, 2016). "Harris never searched hot-car deaths on web, detective acknowledges". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Boone, Christian (October 17, 2016). "Friend testifies he shared child-free site with Ross Harris as a joke". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Boone, Christian (October 14, 2016). "Witness: Ross Harris didn't do a 'child-free lifestyle' web search". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Cuevas, Mayra (November 15, 2016). "Jury finds Justin Ross Harris guilty of murder in son's hot car death". CNN. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Luperson, Alberto (June 22, 2022). "Citing 'Far from Overwhelming' Evidence, Georgia Supreme Court Overturns Conviction of Justin Ross Harris in 1-Year-Old Son's Hot Car Death". Law & Crime. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Boone, Christian. "Ross Harris' wife, Leanna, sues for divorce". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ "Ex-wife says dad in son's hot car death "destroyed my life"". www.cbsnews.com. November 2, 2016. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ Jensen, Hope (April 22, 2019). "Minute-by-minute: Day 19 of the Ross Harris hot car death trial". WSB-TV. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Gatlin, Arielle (November 2, 2016). "Defense witnesses unaware of Harris' secret life". WKYC.

- ^ a b "Expert: Father's memory lapse could account for toddler's hot car death". CBS News. November 3, 2016. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ "Hot Car Death: Justin Ross Harris Appeals His Conviction for Murder of Toddler Son". People. January 6, 2017. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ Boone, Christian (May 21, 2021). "Justin Ross Harris denied new trial". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ Rankin, Bill (January 18, 2022). "Lawyer argues Justin Ross Harris wrongly convicted in hot-car chase". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ "Ross Harris: Georgia Supreme Court reverses conviction in toddler's hot car death". WAGA-TV. June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Harris v. The State, 314 Ga. 238 (Supreme Court of Georgia).

- ^ a b Brumback, Kate (June 22, 2022). "Murder conviction overturned in Georgia hot car death case". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Andone, Dakin; Burnside, Tina (June 22, 2022). "Georgia Supreme Court overturns Justin Ross Harris' murder conviction in his son's hot-car death". CNN. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Blitzer, Ronn (June 22, 2022). "Justin Ross Harris, Georgia man convicted in baby son's hot car death, has verdict overturned". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Brumback, Kate (May 25, 2023). "Murder, cruelty charges dismissed in Georgia toddler's hot car death". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Darnell, Tim (May 25, 2023). "Justin Ross Harris will not be retried in son's hot car-related death". WANF. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.