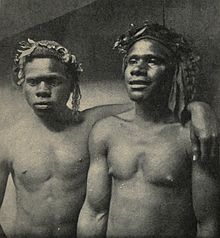

Kanaka (Pacific Island worker)

Kanakas were workers (a mix of voluntary and involuntary) from various Pacific Islands employed in British colonies, such as British Columbia (Canada), Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Queensland (Australia) in the 19th and early 20th centuries. They also worked in California (United States) and Chile (see also Easter Island and the Rapa Nui).

"Kanaka" originally referred only to Native Hawaiians, from their own name for themselves, kānaka ʻōiwi or kānaka maoli, kānaka meaning "man" in the Hawaiian language.[1] In the Americas in particular, native Hawaiians were the majority; but Kanakas in Australia were almost entirely Melanesian. In Australian English "kanaka" is now avoided outside of its historical context, as it has been used as an offensive term.[2]

Australia

[edit]

According to the Macquarie Dictionary, the word "kanaka", which was once widely used in Australia, is now regarded in Australian English as an offensive term for a Pacific Islander.[2][3] Most "Kanakas" in Australia were people from Melanesia, rather than Polynesia. The descendants of 19th century immigrants to Australia from the Pacific Islands now generally refer to themselves as "South Sea Islanders", and this is also the term used in formal and official situations.

Most of the original labourers were recruited or blackbirded (kidnapped or deceived) from the Solomon Islands, New Hebrides (Vanuatu) and New Caledonia, with others from the Loyalty Islands.

The first shipload of 65 Melanesian labourers arrived in Boyd Town on 16 April 1847 on board the Velocity, a vessel under the command of Captain Kirsopp and chartered by Benjamin Boyd.[4] Boyd was a Scottish colonist who wanted cheap labourers to work at his expansive pastoral leaseholds in the colony of New South Wales. He financed two more procurements of South Sea Islanders, 70 of which arrived in Sydney in September 1847, and another 57 in October of that same year.[5][6] Many of these Islanders soon absconded from their workplaces and were observed starving and destitute on the streets of Sydney.[7] After the report of the alleged murder of the Native Chief of the Island of Rotumah in 1848, a closed-door enquiry was held, choosing not to take any action against Boyd or Kirsopp.[8] The experiment of utilising Melanesian labour was discontinued in Australia until Robert Towns recommenced the practice in the early 1860s.

After 1863, more than 62,000 Islanders were brought to Australia; in 1901, about 10,000 were living in Queensland and northern New South Wales.[9] The Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901,[10] legislation complementing the White Australia policy, ordained the deportation of all post-1879 arrivals to the Solomon Islands or the New Hebrides, where "neither property, nor rights, nor welcome awaited them".[11] Antonius Tua Tonga, a Kanaka who had lived in Queensland since the age of four, petitioned the King of England for a mitigation of the legislation, but the Australian prime minister, Alfred Deakin, advised the British government the petition was a front for planters, and the deportations took place largely as intended. A legislative amendment in 1905 exempted those of "extreme age", those married to whites, and freeholders. The prime minister, Alfred Deakin, declined to exempt those schooled in Australia.[12]

The descendants of those who avoided deportation today form Australia's largest Melano-Polynesian ethnic group. Many Australian South Sea Islanders are also of mixed ancestry, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, for whom they are often mistaken. As a consequence, Australian South Sea Islanders have faced forms of discrimination similar to Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders.

After 1994, the Australian South Sea Islander community was recognised as a unique minority group, following a report by the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, which found they had become more disadvantaged than indigenous Australians.[13]

Canada

[edit]

Canadian Kanakas were all Hawaiian in origin. They had been aboard the first exploration and trading ships to reach the Pacific Northwest Coast. There were cases of Kanakas jumping ship then living amongst various First Nations peoples. The first Kanakas to settle came from Fort Vancouver after clearing the original Fort Langley site and building the palisade (1827). They were often assigned to the fur brigades and Express of the fur companies and were a part of the life of company forts. A great many were contracted to the Hudson's Bay Company while some had arrived in the area as ship's hands. In other instances, they migrated north from California. The Kanaka Rancherie was a settlement of Native Hawaiian migrant workers in Vancouver.

Many Kanaka men married First Nations women,[14] and their descendants can still be found in British Columbia and neighbouring parts of Canada, and the United States (particularly in the states of Washington and Oregon). Kanaka Creek, British Columbia, was a community of mixed Hawaiian-First families established across the Fraser River from Fort Langley in the 1830s, which remains on the map today.

Kanakas were active in both the California Gold Rush, and in the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush and other rushes. Kanaka Bar, British Columbia gets its name from claims staked and worked by Kanakas who had previously worked for the fur company (which today is a First Nations community of the Nlakaʼpamux people).

There were no negative connotations in the use of Kanaka in British Columbian and Californian English of the time, and in its most usual sense today, it denotes someone of Hawaiian ethnic inheritance, without any pejorative meaning.

One linguist holds that Canuck, a nickname for Canadians, is derived from the Hawaiian Kanaka.[15]

United States

[edit]The first native workers from the Hawaiian Islands (called the "Sandwich Islands" at the time) arrived on the Tonquin in 1811 to clear the site and help build Fort Astoria, as undertaken by the Pacific Fur Company. Nearly 12 Kanakas or a third of the workforce wintered over among "Astorians". Kanakas built Fort Elizabeth on the island of Kauai in Hawaii for the Russian American Company in 1817, with others to follow.

By the 1820s, Kanakas were employed in the kitchen and other skilled trades by the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver, mostly living south and west of the main palisade in an area known as "Kanaka Village." Kanakas, employed in agriculture and ranching, were present in the mainland United States as early as 1834, primarily in California under Spanish colonial rule, and later under American company contracts. (Richard Henry Dana refers often to Kanaka workers and sailors on the Californian coast in his book Two Years Before the Mast).

The migration of Kanakas peaked between 1900 and 1930, and most of their families soon blended by intermarriage into the Chinese, Filipino, and more numerous Mexican populations with whom they came in contact. At one point, Native Hawaiians harvested sugar beets and picked apples in the states of Washington and Oregon.

The Kanakas have left a legacy in Oregon place names, such as Kanaka Flat in Jacksonville, the Owyhee River in southeastern Oregon (Owyhee is an archaic spelling of Hawaii)[16][17] and the Kanaka Gulch.[18]

See also

[edit]- Kanak: indigenous people of New Caledonia (also known as Kanaky)

- Kanake: German racial epithet

- Blackbirding

- Haole

- Indentured servant

- Coolies

- Slavery

References

[edit]- ^ "Etymology, origin and meaning of kanaka by etymonline". Etymonline. 28 September 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ a b Macquarie Dictionary (Fourth Edition), 2005, p. 774

- ^ "Kanaka dictionary definition - Kanaka defined". www.yourdictionary.com.

- ^ "Exports". Sydney Chronicle. 21 April 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ "Sydney news". The Port Phillip Patriot and Morning Advertiser. 1 October 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ "Shipping intelligence". The Australian. 22 October 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ "The "Phantom" from Sydney". South Australian Register. 11 December 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ "The alleged murder at Rotumah". Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer. 1 July 1848. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via Trove.

- ^

This Wikipedia article incorporates text from From Across the Seas: Tracing Australian South Sea Islanders (19 August 2022) by Christina Ealing-Godbold published by the State Library of Queensland under CC BY licence, accessed on 16 January 2023.

This Wikipedia article incorporates text from From Across the Seas: Tracing Australian South Sea Islanders (19 August 2022) by Christina Ealing-Godbold published by the State Library of Queensland under CC BY licence, accessed on 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 (Cth)". Documenting a Democracy. National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Peter Corris, Passage, Port and Plantation: a History of Solomon Islands Labour Migration, 1870-1914, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1973, p.127.

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889-1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021, p.298.

- ^ "Recognition for Australian South Sea Islanders". Queensland Museum. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Koppel, Tom, 1995 Kanaka: The Untold Story of Hawaiian Pioneers in British Columbia and Pacific Northwest p 2

- ^ Allen, Irving Lewis, 1990. Unkind Words: Ethnic Labeling from Redskin to WASP, pp 59, 61–62. New York: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0-89789-217-8.

- ^ Rabun, Sheila J. (1 June 2011). "Aloha, Oregon! Hawaiians in Northwest History". Oregon Digital Newspaper Program. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Boom, Tony (28 April 2009). "The Hawaiians of Kanaka Flat". Mail Tribune. Medford, OR. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "Jackson County Place Names Database". Jackson County Genealogy Library. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Affeldt, Stefanie: Consuming Whiteness. Australian Racism and the ‘White Sugar’ Campaign. Lit-Verlag, Münster 2014, pp. 152–188

- Barman, Jean, 2006. "Leaving Paradise: Indigenous Hawaiians in the Pacific Northwest", University of Hawaii Press, 513pp. ISBN 0-8248-2549-7

- Maurice Black (1894), A few facts in connection with the Employment of Polynesian Labour in Queensland: 1894, London: Colony of Queensland, Wikidata Q108799620

- Di Giorgio, Wladimir, 2009. "Francs et Kanaks". rés. n°5195 A.P.E/Ctésia

- Alexander James Duffield, What I Know of the Labour Traffic, Brisbane: Walter, Ferguson & Co., Wikidata Q108864821

- Graves, Adrian, 1983. "Truck and Gifts: Melanesian Immigrants and the Trade Box System in Colonial Queensland", in: Past & Present (no. 101, 1983)

- Koppel, Tom, 1995. Kanaka, The Untold Story of Hawaiian Pioneers in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest, Whitecap Books, Vancouver

- Lane, M. Melia, 1985. "Migration of Hawaiians to Coastal B.C., 1810–1869." Master's Thesis, University of Hawaii, Honolulu

- Twain, Mark, 1897. "Following the Equator, A Journey Around the World", chapters V and VI.

External links

[edit]- Australian South Sea Islanders - State Library of Queensland

- Plantation Voices - State Library of Queensland exhibition

- Blog - Sugar Slaves

- Blog - From Across the Seas: Tracing Australian South Sea Islanders

- Immigrants to New Caledonia

- Australian people of Melanesian descent

- Canadian people of Oceanian descent

- American people of Oceanian descent

- Economic history of Fiji

- Labor history of the United States

- Labour history of Australia

- History of British Columbia

- Labour in Canada

- History of New Caledonia

- Alta California

- Fur trade

- British colonisation of Oceania

- Oceanian diaspora in the United States

- Pacific Islands American history

- Slavery in North America

- Slavery in Australia

- Slavery in Asia

- Slavery in South America

- Slavery in Oceania