Pacific Northwest Corridor

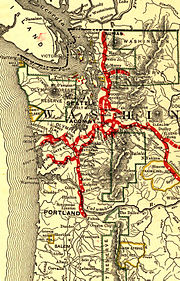

The Pacific Northwest Corridor or the Pacific Northwest Rail Corridor is one of eleven federally designated higher-speed rail corridors in the United States and Canada.[1] The 466-mile (750 km) corridor extends from Eugene, Oregon, to Vancouver, British Columbia, via Portland, Oregon; and Seattle, Washington, in the Pacific Northwest region. It was designated a high-speed rail corridor on October 20, 1992, as the one of five high-speed corridors in the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA).[2]

Current passenger service

[edit]The Pacific Northwest rail corridor is used by several Amtrak and local commuter rail services. Amtrak operates the Amtrak Cascades service over the length of the corridor, as well as the Coast Starlight from Seattle southward. The Empire Builder uses the corridor on short segments, via two sections in Seattle and Portland. BNSF Railway operates Sounder commuter rail for Sound Transit between Seattle and Tacoma, and Seattle and Everett.

History

[edit]Development of the corridor

[edit]What became the Pacific Northwest Corridor was largely developed between the 1860s and the 1910s by the Southern Pacific Railroad, Northern Pacific Railway, and Great Northern Railway. Passenger service declined after the 1910s, but service was present on the whole corridor when Amtrak took over intercity passenger service in the United States on May 1, 1971.

Eugene–Portland

[edit]In 1866, the United States Congress granted land to a then-unnamed railway that would traverse the length of Willamette Valley south from Portland to the California state line.[3] A railway company that would later become Ben Holladay's Oregon Central Railroad began laying track on the east side of the Willamette River in East Portland, Oregon, in April 1868. This railroad reorganized as the Oregon and California Railroad; it was completed as far south as Roseburg, Oregon, by December 1872.[4] In 1887, the Oregon and California was purchased by the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP).[5]

By 1940, the SP operated six daily round trips between Portland and Eugene: five long-distance trains – the Beaver, Cascade, Klamath, Oregonian, and West Coast – that continued to Oakland via the Shasta Route, and the Rogue River local service that ran to Ashland, Oregon, on the older Siskiyou Line.[6] Service gradually was decreased; after September 1966, the Cascade was the only remaining SP service running between Portland and Eugene. It was reduced to tri-weekly service in 1970, but lasted until the start of Amtrak.[7]

Portland–Seattle

[edit]

In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Northern Pacific Charter, which established the Northern Pacific Railway (NP) with the charge of constructing a rail connection between the Great Lakes and Puget Sound.[8] Work on the first section of the railway's right-of-way in Washington Territory began at Kalama in 1870.[9][10]: 11 After an 1873 decision to place the Puget Sound terminus in Tacoma, Washington, scheduled service on the NP's Pacific Division between Kalama and Tacoma began on January 5, 1874.[10]: 11 The NP-affiliated Puget Sound Shore Railroad connected Tacoma to Seattle on July 6, 1884.[11] Rail service between Tacoma and Portland, Oregon (with a ferry between Goble, Oregon and Kalama) began on October 9, 1884.[10]: 12 The original line was extended south from Kalama to Vancouver, Washington, in 1901 by the Washington Railway & Navigation Company, which was soon acquired by the NP. In 1906, the Portland and Seattle Railroad Company – a joint venture of the NP and the Great Northern Railway (GN), both owned by James J. Hill, began construction of the final link from Vancouver into Portland. The 1908 opening of the Columbia River bridge completed the all-rail route ("Prairie Line") between Seattle and Portland, eliminating the need for the ferry crossing at Kalama.[10]: 12 [12]

By August 1909, the NP ran four daily round trips between Portland and Seattle.[10]: 12 The next January, the NP signed an agreement with the Oregon–Washington Railroad and Navigation Company – a subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) – giving the UP trackage rights over the Prairie Line. A similar agreement with the GN was reached that June.[10]: 12 By May 1914, three railroads ran some 11 daily Seattle–Portland round trips (4 NP, 4 UP, and 3 GN) plus a number of freight trains.[10]: 12 The GN used the 1884-built NP route into 1906-built King Street Station in Seattle, while the UP used the 1909-built Milwaukee Road line into Union Station.[13] The substantially increased passenger service on the NP required the original single-track mainline to be straightened and double tracked. This was completed between Portland and Kalama in 1909, and between Kalama and Tenino, Washington, around 1915.[10]: 12

However, the section of the Prairie Line between Tenino and Tacoma had a 2.2-mile (3.5 km) section of difficult 2.2% grade. The NP opened Tacoma Union Station and the new water-level Point Defiance Line around Point Defiance in December 1914.[10]: 12 [14] The southern 6 miles (9.7 km) between Tenino and Plumb, Washington, was reused from the Olympia Branch of the Port Townsend Southern Railroad, purchased earlier that year, while a short section east of Olympia used the 1891-opened Tacoma, Olympia & Grays Harbor Railroad.[10]: 12 [15][16] Although slightly longer than the Prairie Line, the Point Defiance Line was substantially flatter. The UP moved all service to the new line, and the NP moved most service, though the GN continued to use the old line.[10]: 12

By the mid-1920s, the GN, NP, and UP began operating "Pool Service", where tickets were cross-honored between the three railroads on their Seattle–Portland services.[17] In 1933, the three railroads reduced service to one daily round trip each – a level maintained for several decades.[10]: 14 The GN trip was moved to the Point Defiance Line on August 8, 1943, ending through service on the Prairie Line north of Tenino, and the last passenger service between Tacoma and Grays Harbor via Olympia and Lakewood ended in February 1956.[10]: 15 The GN and NP were merged into the Burlington Northern Railroad (BN) in 1970. Final pre-Amtrak BN-UP Pool Service consisted of three daily round trips – one (UP) to Union Station, and two (BN) to King Street.[18] The original line was upgraded in the 2010s, with Sounder and Amtrak service added via the Point Defiance Bypass.

Seattle–Vancouver

[edit]The original line from Seattle to Vancouver, British Columbia, was completed by four separate companies which were soon consolidated under James J. Hill's Great Northern Railway (GN) to provide the GN with two Pacific ports. The Fairhaven and Southern Railroad (F&S) was completed from Sedro, Washington, to Fairhaven, Washington, in late 1889, with an extension along the shoreline to the international border at Blaine, Washington, completed on October 25, 1890.[19]: 215–216 The Hill-controlled New Westminster Southern Railway was simultaneously completed from Brownsville, British Columbia (across the Fraser River from New Westminster) to the international border, where it was connected to the F&S on January 10, 1891.[19]: 215 In 1890, Hill incorporated the Seattle and Montana Railroad, which acquired the struggling F&S and began construction from Seattle northwards to a connection with the F&S in Belfast, Washington.[19]: 262 [20] The first Seattle–Brownsville through train ran on November 27, 1891; regular service began on December 4.[19]: 262 [20] The GN transcontinental route was completed in 1893; it connected to the Seattle and Montana at Everett, Washington.[21]: 73–74

In August 1902, the John Hendry-owned Vancouver, Westminster and Yukon Railway began construction of a line from the rapidly growing city of Vancouver, British Columbia, to New Westminster, with a bridge crossing the Fraser River to connect with the GN. The GN gained access to Vancouver with the completion of the New Westminster Bridge and the VW&Y in late 1904.[21]: 78 The New Westminster Southern was formally purchased by the GN in 1891, the Seattle and Montana in 1907, and the VW&Y via its Canadian subsidiary Vancouver, Victoria and Eastern Railway and Navigation Company (VV&E) in 1908 after years of poor relations, formalizing GN control of the corridor.[19]: 261 [21]: 74, 90

The GN was not the first Seattle–Vancouver rail route—the Northern Pacific-owned Seattle, Lake Shore and Eastern Railway (SLS&E) was completed from Seattle to a connection with the Canadian Pacific Railway at Mission, British Columbia, in 1891.[21]: 73 However, the inland SLS&E route had numerous curves and steep grades; Hill had considered purchasing it in 1890, but deciding that constructing the Seattle and Montana would allow superior service.[20] Passenger service ended on the SLS&E in the mid-1920s, leaving the GN as the only Seattle–Vancouver passenger route.[22]

Several portions of the route were realigned in the first decades of the 20th century. Replacement of leased trackage with GN-owned trackage in Everett, including a new tunnel under the downtown area, was completed on October 7, 1900.[23][24] A tunnel into downtown Seattle opened in 1905 to reach King Street Station, which opened the next year.[25][26] Construction began in 1901 on the Chuckanut Cutoff, which ran at water level along Bellingham Bay between Fairhaven and Belleville (north of Burlington, Washington) to bypass the numerous sharp curves on the original F&S route.[27] The cutoff opened on February 15, 1903, and the original F&S line was abandoned from Fairhaven to Lake Samish.[28] The Great Northern and VV&E opened a new coastal route with lower grades from Brownsville to Blaine on March 15, 1909.[29] The construction of the Lake Washington Ship Canal in Seattle, which began in 1911, necessitated the replacement of the single-track bridge connecting Interbay Yard and Ballard. The new double-track bridge and 2.5 miles (4.0 km) of connecting line opened in 1914.[30]

By 1913, the GN operated four Seattle–Vancouver round trips (three of which continued south to Portland) and one Seattle–Blaine round trip; this decreased to three Seattle–Vancouver round trips by 1928.[31][32] The 1950 introduction of the streamlined International increased daily service to four daily round trips – three Internationals and one unnamed local.[33][34] The GN dropped one International round trip in May 1960, and a second in June 1969.[34] By the time Amtrak began operations, the Burlington Northern ran a single daily International round trip.[18]

Amtrak era

[edit]Initial Amtrak service in 1971 consisted of an unnamed tri-weekly Seattle–San Diego train (later named Coast Starlight-Daylight) and two unnamed Seattle–Portland round trips (later named Mount Rainier and Puget Sound), with no service north of Seattle. The Empire Builder also ran on the corridor between Seattle and the connection with the ex-Northern Pacific mainline at Auburn, Washington.[35] The daily Seattle–Vancouver Pacific International began service on July 17, 1972.[34][36] Coast Starlight-Daylight (later Coast Starlight) service became daily on June 10, 1973, resulting in three daily Seattle–Portland round trips.[37] The Seattle–Salt Lake City Pioneer displaced the Puget Sound on June 7, 1977, with no change to service levels on the corridor.[38][39]: 140 From June 11, 1973, until its discontinuance on October 8, 1979, the North Coast Hiawatha also ran on the corridor between Seattle and the connection with the ex-Great Northern mainline at Everett.[39]: 160, 166

In 1977, the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) studied the possibility of 100-mile-per-hour (160 km/h) service between Portland and Eugene.[40]: 3 Two additional Portland–Eugene round trips were added on August 3, 1980, with the introduction of the state-subsidized Willamette Valley.[41] The Pacific International was discontinued on September 30, 1981, ending service north of Seattle.[42][43]: 52 The stops at Edmonds and Everett were restored on October 25 when the Empire Builder was rerouted over the ex-GN mainline. A Portland section of the Empire Builder, which ran on the corridor between Portland and Vancouver, Washington, was also created at that time.[39]: 172 The Willamette Valley was discontinued on December 31, 1981, after state funding was ended.[44] Service remained largely constant until November 4, 1993, when the Pioneer was reduced to tri-weekly service.[39]: 149

Expanded service

[edit]The 1991 passage of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act resulted in the designation of five high-speed-rail corridors in October 1992 – among them the Eugene–Vancouver Pacific Northwest High-Speed Rail Corridor.[40]: 4 Between 1992 and 1994, ODOT studied service improvements on the Portland–Eugene section of the corridor.[40]: 3 Several reports produced by the Washington Department of Transportation in 1992 indicated that maglev service on an all-new right-of-way or electrification of the existing corridor would be impractical, leaving enhancements to diesel-powered trains as the likely option for improved service.[45]: 1–5 In 1993, the Washington legislature allocated funds for the development of incremental improvements to Amtrak service in the state.[46]: 6–1 Daily service was to be eventually increased to 13 Seattle–Portland round trips and 4 Seattle–Vancouver round trips. Tilting trains and infrastructure improvements were to be used to decrease travel times – from 4 hours to 2.5 hours between Seattle and Portland, and from 4 hours to 3 hours between Seattle and Vancouver.[45]: 1–6 Work on a corridor-level Environmental Impact Statement for the Washington section of the corridor began in January 1996; however, it was suspended in August 2000 in favor of less intensive environmental documentation for individual projects.[46]: ES-3

Parallel to this infrastructure planning, the states began funding service expansions on a trial basis. On April 1, 1994, Washington began a 6-month trial of a rented Talgo tilting trainset, which was used to add an additional Seattle–Portland round trip called Northwest Talgo.[47] On October 1, 1994, the Northwest Talgo was replaced by the Mount Adams using conventional equipment.[48][49] ODOT funded an extension of the Mount Rainier to Eugene, which began on October 30.[50][51] WSDOT also funded the Seattle–Vancouver Mount Baker International, which began service on May 26, 1995, using the rented Talgo set previously used on the Northwest Talgo.[42][52]

Modern changes

[edit]Current investment in passenger rail in the Pacific Northwest Corridor will not be used to create a dedicated high speed passenger rail corridor from the ground up, but will instead create more modest systematic improvements to the existing railway used by the Amtrak Cascades line that uses trackage owned primarily by private freight railways. On January 27, 2010, the federal government announced $590 million of ARRA stimulus funds would go to Washington State for higher speed improvements of its section of the corridor. Additionally, the state of Oregon received $8 million to improve Portland's Union Station and trackways in the area.[53] On December 9, 2010, US Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood announced that Washington State would receive an additional $161 million in federal higher-speed rail funding from the Federal Rail Administration after newly elected governors in both Wisconsin and Ohio turned down their states' high-speed rail funding. This brought Washington's total funding to about $782 million.[54] These investments funded the construction of the Point Defiance Bypass, which reduced travel times and enabled the addition of two extra trips in the Seattle-Portland Amtrak Cascades corridor daily.

Ultra high speed rail

[edit]In July 2017, the Washington State Legislature budgeted $300,000 for a preliminary feasibility study of "Ultra High Speed ground transportation" operating at speeds of 250 miles per hour (400 km/h) or more, linking Vancouver, BC, to Seattle and Portland.[55] This study[56] was completed by December that year, and analysed technology options, route options, preliminary financing and funding models, and recommended conducting a more detailed business case analysis that will examine ridership projections, governance, funding and financing models in greater detail. Microsoft paid $60,000 for this preliminary study, and had also earlier sponsored an economic analysis report which served as the catalyst for this preliminary study commissioned by Washington state[57]

In March 2018, Washington state authorized up to $750,000 to be spent on conducting a detailed business case analysis as recommended by the preliminary feasibility study, if additional funding sources could be identified.[58] In July 2018, Washington governor Jay Inslee travelled to Vancouver, British Columbia, to meet with B.C. Premier John Horgan. As a result of that and other meetings, additional funding sources were identified and eventually increased to around US$1.55 million and came from 4 sources: CA$300,000 from the B.C. provincial government, US$750,000 from Washington State, US$300,000 from Oregon's Department of Transportation, and US$300,000 from Microsoft.[59] In October 2018, the Cascadia Innovation Corridor Conference, a Microsoft co-sponsored, cross-border initiative to encourage cross border business investment and collaboration, met for the third time, where one of the topics was to discuss updates on the high-speed rail business case analysis.[60]

In January 2019, the Washington State Legislature passed a bill that approved up to $900,000 to study the creation of a high-speed rail authority in Washington state if additional funding sources could be identified.[61][62][63] Again, Jay Inslee travelled to Vancouver to meet with John Horgan, and as a result, Horgan announced that the BC provincial government would contribute CA$300,000 towards studying a cross-border governance model for the high speed rail authority.[64] Additional funding for the balance came later on from Oregon and Microsoft.[65]

In July 2019, the business cases analysis was completed and a detailed report was submitted to WSDOT. The detailed report confirmed that an ultra-high-speed rail system could be constructed within the 2017 estimate of $24 to $42 billion and help establish the Pacific Northwest as a megaregion if construction were to start by 2027.[65] [66] Later in the year, various groups held conferences to discuss the findings of the business case analysis and promote ultra-high-speed rail in general.[67][68] The most notable conference was the Cascadia Rail Summit held in November 2019, held at Microsoft's headquarters in Redmond, Washington, which brought participants from private corporations, pro-business non-profits, government organizations and universities from both sides of the border.[69][70]

In November 2021, a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to bring high-speed rail to the Cascadia Corridor was signed by Washington Governor Jay Inslee, Oregon Governor Kate Brown, and British Columbia Premier John Horgan.[71]

References

[edit]- ^ "Previous HSR Corridor Descriptions". Federal Railroad Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ "Chronology of High-Speed Rail Corridors". Federal Railroad Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Sanger, George P., ed. (1868), Statutes at Large, Treaties and Proclamations, of the United States of America from December 1865 to March 1867, vol. XIV, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, p. 239, retrieved March 5, 2011

- ^ Carey, Charles Henry (1922), History of Oregon, Portland: The Pioneer Historical Publishing Company, pp. 685–695, retrieved March 5, 2011

- ^ Robertson, James R. (March 1902). "The Social Evolution of Oregon". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. III (1). Oregon Historical Society: 26. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Southern Pacific Time Tables: Shasta Route (PDF). Southern Pacific Railroad. August 1940. pp. 4–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ Stafford, George M. (December 29, 1970). "Interstate Commerce Commission Comments on Railpax Plan". Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 91st Congress, Second Session. Vol. 116, no. 33. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 43934. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ "Washington State Amtrak Cascades Mid-Range Plan" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation State Rail and Marine Office. December 2008. pp. 2–1. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2009. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Schwantes, Carlos A. (1993). Railroad Signatures across the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-295-97535-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "1: Catalog" (PDF). Prairie Line Terminal Section: Catalog of Character-Defining Features. University of Washington, Tacoma. April 2011. pp. 9–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ Armbruster, Kurt E. (Winter 1997–98). "Orphan Road: The Railroad Comes to Seattle". Columbia Magazine. Vol. 11, no. 4. pp. 7–18. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011.

- ^ Baltimore, J. Mayne (June 1908), "Western Railroad Activities", Locomotive Fireman and Enginemen's Magazine, 44 (6), Indianapolis, Indiana: Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen: 809, archived from the original on March 14, 2023, retrieved November 8, 2018

- ^ Corley, Margaret A. (July 1969). "NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACE INVENTORY – NOMINATION FORM". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ "Officials Look Over New Road", The Tacoma Times, vol. XI, no. 296, Tacoma, p. 8, December 1, 1914, archived from the original on July 21, 2011, retrieved March 6, 2011

- ^ Poor's and Moodys manual consolidated (Moody's Manual of Railroads and Corporation Securities), vol. I, New York: Moody Manual Company, 1915, p. 653, archived from the original on March 14, 2023, retrieved November 9, 2018 – via Google Books

- ^ Robertson, Donald B. (1986). Encyclopedia of Western Railroad History: Oregon, Washington. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press. p. 292. ISBN 9780870043666. OCLC 13456066. Retrieved December 18, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Northern Pacific Time Tables. Northern Pacific Railway. June 1926. pp. 27–28 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ a b Burlington Northern time table. Burlington Northern Railroad. April 26, 1970 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ a b c d e Robertson, Donald B. (1986). Encyclopedia of Western Railroad History. Vol. III: Oregon &bull,  , Washington. Caxton Press. ISBN 9780870043666 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c "Joy Along the Line". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. November 28, 1891. p. 8. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Leonard, Frank (Autumn 2007). "Railroading a Renegade: Great Northern Ousts John Hendry in Vancouver". BC Studies (155): 69–92. doi:10.14288/bcs.v0i155.629. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ Hansen, David M. (November 1970). "NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY – NOMINATION FORM". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ Woodhouse, Philip R.; Jacobson, Daryl; Petersen, Bill (September 2000). "Chapter 3: The Railroad's Early Years". The Everett & Monte Cristo Railway (PDF). Oso Publishing. p. 38. ISBN 0964752182. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ "New Lines". Twelfth Annual Report of the Great Northern Railway Company. Great Northern Railway Company. 1901. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Corley, Margaret A. (July 1969). "NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY – NOMINATION FORM". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ "Additions and Improvements". Sixteenth Annual Report of the Great Northern Railway Company. Great Northern Railway Company. 1905. p. 19. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ "Construction". The Railway Age. Vol. 31, no. 25. June 21, 1901. p. 680. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Revision of Lines". Fourteenth Annual Report of the Great Northern Railway Company. Great Northern Railway Company. 1903. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ "New Line". Twentieth Annual Report of the Great Northern Railway Company. Great Northern Railway Company. 1909. p. 15. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Adams, E.E. (August 20, 1914). "Great Northern Ry. Improvements at Seattle, Wash". Engineering News. Vol. 72, no. 8. pp. 377–379. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Local Time Tables (PDF). Great Northern Railway. November 1913. pp. 36–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via Streamliner Memories.

- ^ Great Northern Time Tables (PDF). Great Northern Railway. p. 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via Streamliner Memories.

- ^ Passenger Train Schedules (PDF). Great Northern Railway. May 29, 1955. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2018 – via Streamliner Memories.

- ^ a b c Glischinski, Steve (October 27, 2015). "Amtrak 'Cascades' celebrate 20 years in service". Trains News Wire. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ Nationwide Schedules of Intercity Passenger Service. National Railroad Passenger Corporation. May 1, 1971. p. 26. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2018 – via Museum of Railway Timetable.

- ^ Thoms, William E. (1973). "Amtrak Revisited: The 1972 Amendments to the Rail Passenger Service Act" (PDF). Transportation Law Journal. 5: 143. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ Amtrak All-America Schedules. National Railroad Passenger Corporation. June 10, 1973. p. 41. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2018 – via Museum of Railway Timetables.

- ^ Amtrak National Train Timetables. Amtrak. June 22, 1977. p. 59. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2018 – via Museum of Railway Timetable.

- ^ a b c d Sanders, Craig (2006). Amtrak in the Heartland. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34705-3.

- ^ a b c "U.S. System Summary: PACIFIC NORTHWEST" (PDF). Texas Central Railway. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Preview Run Heralds New Willamette Valley Trains" (PDF). Amtrak News. Vol. 7, no. 8. Amtrak. September–October 1980. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ a b Angus, Fred F. (May–June 1996). "Twenty-Five Years of Amtrak in Canada" (PDF). Canadian Rail. No. 452. pp. 63–73. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Solomon, Brian (2004). Amtrak. Saint Paul, Minnesota: MBI. ISBN 978-0-7603-1765-5.

- ^ "Amtraking" (PDF). The Trainmaster. No. 245. Pacific Northwest Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society. January 1982. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Long-Range Plan for Amtrak Cascades" (PDF). Washington Department of Transportation. February 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Program Environmental Assessment" (PDF). Pacific Northwest Rail Corridor: Washington State Segment – Columbia River to the Canadian Border. Washington State Department of Transportation. September 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Esteve, Harry (March 31, 1994). "Talgo 200 tantalizes train fans". Eugene Register-Guard. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 22, 2018 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ Robinson, Erik (September 29, 1994). "High-speed train runs end on Friday". Centralia Chronicle. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Godfrey, John (May–June 1996). "The Northwest Talgo" (PDF). Canadian Rail. No. 452. pp. 74–75. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Bishoff, Don (November 2, 1994). "Seattle in six, and a nap, too". Eugene Register-Guard. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved November 22, 2018 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ Amtrak National Timetable: Fall/Winter 1994/1995. Amtrak. October 30, 1994. p. 35. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2018 – via Museum of Railway Timetable.

- ^ Stall, Bill (May 21, 1995). "Out of Step on a Landmark in Rome". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ ""Washington to get $590 million for higher-speed rail improvements" Seattle Times retrieved 2010-01-28". Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ ""Washington state awarded additional federal high-speed rail funds" Washington State Department of Transportation retrieved 2010-12-09". Archived from the original on December 12, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Banse, Tom (July 26, 2017). "By Bullet Train From Portland To Seattle To Vancouver, BC? Feasibility Study Underway". KUOW. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ CH2M Hill (February 2018). "Ultra High Speed Ground Transportation Study" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Staltman, Jennifer (December 15, 2017). "Vancouver to Seattle in an hour? Ultrafast rail study brings it one step closer". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Fesler, Stephen (March 13, 2018). "High-Speed Rail in Cascadia Will Get a Deeper Look, Report Due Mid-2019". theurbanist.org. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Penner, Derrick (July 26, 2018). "Governments commit US$1.5-million for further study of Cascadia high-speed train". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Staff (October 2018). "2018 Cascadia Innovation Corridor Conference Materials" (PDF). Connect Cascadia. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Scruggs, Gregory (December 4, 2019). "The Case for Portland-to-Vancouver High-Speed Rail". Bloomberg CityLab. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ "Bill introduced for high-speed rail authority in Northwest". MyNorthwest.com. January 18, 2019. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Fesler, Stephen (January 17, 2019). "Cascadia Interstate High-Speed Rail Authority Chugging Toward Legislative Approval". The Urbanist. Archived from the original on January 27, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Meherally, Almas (February 7, 2019). "B.C. to fund next phase of ultra-high-speed Cascadia corridor study". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Chan, Kenneth (July 16, 2019). "High-speed rail connecting Vancouver, Seattle, and Portland worth the cost: report". The Daily Hive. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Orton, Tyler (July 15, 2019). "Vancouver-Seattle-Portland high-speed rail zips closer to reality with new business case". Business In Vancouver. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Trumm, Doug (October 4, 2019). "Wide Support for High-Speed Rail at Cascadia Conference, Plus Skeptic Transpo Chair DeFazio". The Urbanist. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Bernardo, Marcella (October 6, 2019). "B.C., Washington and Oregon fast-tracking high-speed rail corridor across Pacific Northwest". CityNews. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Boynton, Sean (November 7, 2019). "Experts, officials meet at Microsoft HQ to discuss high-speed rail between Vancouver and U.S." Global News. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Staff (November 2019). "Cascadia Rail summit". US High Speed Rail Association. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Bishop, Todd (November 16, 2021). "Rapid rail for Cascadia? B.C., Washington and Oregon sign pact on high-speed transportation". GeekWire. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2021.