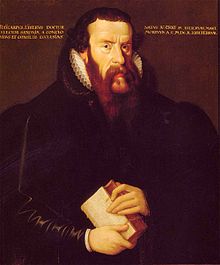

Polykarp Leyser the Elder

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (September 2016) |

Polykarp (von) Leyser the Elder or Polykarp Leyser I (18 March 1552 – 22 February 1610) was a Lutheran theologian, superintendent of Braunschweig, superintendent-general of the Saxon church-circle, professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg and chief court-preacher and consistorial-councillor of Saxony.[1]

Leyser was born in Winnenden. In 1580, he married Elisabeth, the daughter of Lucas Cranach the Younger, and their children included Polykarp Leyser II (1586–1633), another theologian. This made him the founder of a dynasty of theologians, as great-grandfather of Polykarp Leyser III (1656–1725) and great-great-grandfather of Polykarp Leyser IV (1690–1728).[2]

Supported by his father, his uncle Andreae and later his stepfather Osiander, and also with input from his teacher Martin Chemnitz, Leyser came to have an ingrained support for Lutheran orthodoxy – indeed, at a difficult time for Lutheranism, he was one of those who founded that orthodoxy. In the creative force of his Loci theologici (1591/92), Harmonia evangelica (1593), Postilla (1593) and De controversiis iudicium (1594), his theological position was forged by the dispute sparked by (Crypto-)Calvinism in Saxony, by the 'Exorzismusstreit', by the difficulties over Lutheran Christology and by Huber's debate. Leyser is thus to be accounted one of the key figures of the Lutheran concord in northern and central Germany and was constantly attacked in pamphlets as the 'pope of Dresden'. As one of the key movers behind the Formula of Concord, he used his books to defend Lutheran orthodoxy and attack Catholicism and Calvinism, was commissioned by the elector to join several of the meetings which led to the Book of Concord and advocated that the number of sponsors be limited to three people.

He wrote more than sixty theological works and an extensive corpus of sermons. He also dealt with the literary controversies of his time, cultivating an extensive correspondence of 200 written by him and 5000 written to him – an extensive selection from it was first published by his great-grandson Polycarp Leyser III as Sylloge epistolarum in 1706.

Life

[edit]Education

[edit]Polykarp's father Kaspar Leyser (20 July 1526 – end of 1554, Nürtingen) was a pastor in Winnenden then in Nürtingen, giving Polykarp an insight into theology at an early age. Kaspar agreed with Jacob Andreae that government of the laypeople should remain entirely in the pastors' hands, amounting to the establishment of a denomination-wide consistory. He also corresponded with John Calvin, who reserved judgement on the project. They incurred the disapproval of Christoph, Duke of Württemberg. At the instigation of Johannes Brenz this suggestion failed, since Brenz feared it would lead to the church in Württemberg losing control to a centralised consistory.

Polykarp's mother Margarethe was a daughter of Johannes Entringer (a merchant from Tübingen), making her a sister of Jakob Andreaes. On Kaspar's death in 1554, she remarried to Lucas Osiander the Elder. In 1556 the family moved to Blaubeuren, where Polykarp attended the Klosterschule and grew up alongside three of Lucas's sons. In 1562 he continued his education in the Pädagogium in Stuttgart. On his mother's death in 1566 his stepfather sent him to the University of Tübingen, where he studied Protestant theology on a ducal stipend.

In Tübingen he met Ägidius Hunnius the Elder, soon becoming close friends with him. In 1570 he became a Master of Arts and soon became a 'Stiftsrepetent'. His main theological influences at this time were Jacob Heerbrand, Andreae and Erhard Schnepf. Leyser distinguished himself with outstanding exam results and so in 1572 Andreae let him take over leadership of disputations on the doctrine of justification by faith. In 1573 he was ordained and was granted a parish in Göllersdorf in lower Austria, where he joined the imperial councillor and erbtruchsess Michael Ludwig von Puchheim (1512–1580), who introduced him to court life under Maximilian II. He soon made his mark in Graz and wanted to look for a job there, but Osiander and Puchheim discouraged him. Instead he returned to Tübingen, where he rose to become a doctor of theology on 16 July 1576 alongside his friend Hunnius. Initially he had limited job prospects, but this was soon to change.

Wittenberg

[edit]Wittenberg University had seen drastic changes in personnel since 1574 due to the overthrow of the Philippists, along with student discontent against the lecturers. After the death of Kaspar Eberhard, head of the theology department, in October 1575, the students asked David Chytraeus to take over the Generalsuperintendentur in Wittenberg – he refused the offer. Next, in November 1575, they chose Leyser, who accepted. With the post came that of parish priest of the Stadtkirche Wittenberg.

At first Leyser was merely on a two-year loan from Louis III, Duke of Württemberg to Augustus, Elector of Saxony. On 20 January 1577 he preached a trial sermon in Dresden. On 3 February he was formally inducted into his role at Wittenberg. Leyser then made quick trip from Dresden to Austria to "pick up his bags". On 12 May he was back in Wittenberg and took up his official duties, aged only 25. Such a young man holding the highest church office in Wittenberg, before even being noticed in theological circles in Saxony, attracted much attention and some imputed his appointment to nepotism – until 8 June he was not even a professor of the theology department and until 20 November 1577 not a member of the consistory.

However, Leyser's calming of the situation after the expulsion of the Crypto-Calvinists and the reorganisation of the university was so successful that his critics were soon silenced. He was best served by his rhetorical skills and by an undemanding and reliable character, increasing his popularity among his students, including Philipp Nicolai and Johann Arndt. Leyser's skills were also seen in the drafting of the Formula of Concord and the publication of the Book of Concord in 1580. He developed close links with Martin Chemnitz and Nikolaus Selnecker. Leyser and Selnecker were asked to sign up to a Commission in Saxony on the Formula, that Leyser himself had signed on 25 June 1577 as first minister.

He immediately took part in the important theological meetings in Saxony, acting as their recording secretary. The inhabitants of Wittenberg always saw him as an outsider, however, and acted as a thorn in his side. To neutralise this he married a local girl in March 1580, namely Elisabeth, daughter of the painter Lucas Cranach the Younger. The marriage took place in the Wittenberger Rathaus and was overshadowed by student rioting and heavy drinking, which the town authorities had to deal with later.

In 1581 Leyser was again a 'visitator' to the Saxon Electoral Circle, where he was mainly concerned with primary education and the Fürstenschule in Meissen, Schulpforta and Grimma. His publications at this time were limited to funeral sermons and disputations, above all attacking opponents of the Formula of Concord. Tilemann Hesshus was his bitterest opponent at this time in the enforcement of 'Ubiquitätslehre'. The disputes were fought at symposia, including one at 1583 in Quedlinburg, where Leyser witnessed the last speech by his mentor Chemnitz. On 9 September 1584 the superintendent of Brunswick resigned and its inhabitants wanted Leyser to take over the post, but he refused it on Selnecker's advice due to his obligations to Augustus of Saxony.

Leyser gave Augustus's funeral oration after the latter's death in August 1586. His successor, Christian I, tended towards Calvinism and so this began to prevail. Christian freed pastors and teaching staff from their obligation to sign the Formula of Concord at their ordination. Considered to be the main representative of the Lutheran concord under Augustus, Leyser was increasingly exposed to the hostility of Nikolaus Krells and Johann Major, whose influence in the university and Konsistorialangelegenheiten was rising. Leyser was so incensed by this hostility that he warned his students off studying for a master's degree under Major. When the Calvinist Matthias Wesenbeck was buried in the Schlosskirche at the feet of Martin Luther, Leyser preached the funeral sermon, in which he claimed that Wesenbeck had renounced Calvinism on his deathbed and died a good Lutheran. This provoked such an uproar that Leyser had to move to Brunswick. He died in Dresden.

References

[edit]- ^ Herzog, J.J. (1910). The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge: Innocents-Liudger. New York: Funk and Wagnalls Company. pp. 469–70. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Sommer, Wolfgang (2006). Die lutherischen Hofprediger in Dresden (1st ed.). Germany: Steiner. pp. 115–136. ISBN 9783515089074. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Realenzyklopädie für protestantische Theologie und Kirche. Band 11. 3. Ausgabe. Seite 431.

- "Entry". Zedlers Universallexikon. Vol. 17. p. 381.

- Walter Friedensburg: Geschichte der Universität Wittenberg. 1917.

- Wolfgang Sommer: Die Stellung lutherischer Hofprediger im Herausbildungsprozeß Frühmoderner Staatlichkeit und Gesellschaft. In: Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte. Band 106/3, 1995, Seite 313–328.

- Wittenberger Gelehrtenstammbuch. Herausgeber Historisches Museum Berlin, Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle 1999, ISBN 3-932776-76-3, Seite 327.

- Wolfgang Sommer: Politik, Theologie und Frömmigkeit im Luthertum der frühen Neuzeit ... Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3-525-55182-7.

- Wolfgang Sommer: Die lutherischen Hofprediger in Dresden: Grundzüge ihrer Geschichte ... Steiner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-515-08907-1. [1]

- Christian Peters: Polykarp Leyser in Wittenberg. In: Irene Dingel and Günther Wartenberg (ed.): Die Theologische Fakultät Wittenberg 1502 bis 1602. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-374-02019-4.

- Fritz Roth: Restlose Auswertungen von Leichenpredigten und Personalschriften für genealogische und kulturhistorische Zwecke. Bd. 1, S. 28, R 55

External links

[edit]- Books on and by Polykarp Leyser the Elder in the catalogue of the Deutschen Nationalbibliothek