Proxima Centauri (short story)

| "Proxima Centauri" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Murray Leinster | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Science fiction |

| Publication | |

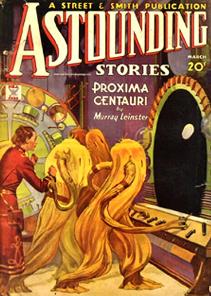

| Published in | Astounding Stories |

| Publisher | Street & Smith |

| Media type | Print (Magazine, Hardback & Paperback) |

| Publication date | March 1935 |

"Proxima Centauri" is a science fiction short story by American writer Murray Leinster, originally published in the March 1935 issue of Astounding Stories. Unusually for the time, the story adhered to the laws of physics as they were known by showing a starship that was limited by the speed of light and took several years to travel between the stars. In his comments on the story in Before the Golden Age, Isaac Asimov thought that "Proxima Centauri" must have influenced Robert A. Heinlein's later story "Universe" and stated that it influenced his own Pebble in the Sky.

Plot summary

[edit]Earth's first starship, the Adastra, is approaching Proxima Centauri after a seven-year voyage. The voyage was marred by a mutiny among the crew, and the ship is still divided between a small group of officers that controls the Adastra and the remainder of the crew, whom the officers refer to disparagingly as Muts, short for mutineers.

A young Mut, named Jack Gary, has been picking up and studying transmissions from a race native to the Proxima Centauri system, which has earned him the confidence of Captain Bradley; the love of Bradley's daughter, Helen; and the hatred of the Adastra's first officer, Commander Alstair, who also has romantic designs upon Helen. Much to Alstair's disgust, Captain Bradley raises Jack to officer status in recognition of his work with the Centaurian transmissions.

Shortly after the elderly Bradley's death, Jack discovers that a Centaurian spaceship is approaching the Adastra, and he suspects that its intention is hostile. The Centaurians confirm his suspicions when they fire a radiation beam at the ship. Although the Adastra has not been harmed, Alstair has the ship play dead to fool the Centaurians into thinking they have succeeded in wiping out the crew. The Centaurian ship docks with the Adastra, and a boarding party attacks the crew. The boarding party is defeated, and the Centaurian ship departs.

Studying the captured leader of the Centaurian boarding party makes it clear that the Centaurians are mobile carnivorous plants that feed on animals and that they look on the crew of the Adastra as a highly valuable food source. Now that the Adastra has entered their system, the Centaurians can trace their course back to Earth. As a fleet of Centaurian ships approaches the Adastra, Jack learns that Earth has launched a second starship for Proxima Centauri.

The defenseless Adastra is surrounded by the Centaurian fleet and boarded. The entire crew is consumed by Centaurians except for Alstair, Jack Gary, Helen Bradley, and half a dozen officers. The Centaurian leader orders all the Adastra's records, equipment, and animals sent on board an automated ship, along with Jack and Helen. While Alstair and the remaining officers pilot the Adastra to Proxima Centauri I, the Centaurian homeworld, the automated ship will be flown to Proxima Centauri II, an Earthlike world that has long since been stripped of its native animal life and abandoned by the Centaurians. After Jack and Helen land on Proxima Centauri II and release the animals there, Alstair reaches the Centaurian homeworld. Alstair rigs the Adastra's engines to explode, which sets off a chain reaction that will destroy the Centaurian homeworld and exterminate the Centaurians. That leaves Jack and Helen to await the arrival of the next ship from Earth.

Reception

[edit]L. Sprague de Camp dismissed the story as "bottom of the trunk", with no virtues beyond "fast action"<.ref>"Book Reviews", Astounding Science Fiction, February 1951, p.151</ref> Everett F. Bleiler reported that the story contains "some good material, some cliche, and some nonsense", concluding that it "seems much less successful" than when it was originally published.[1]

Story notes

[edit]As Asimov notes in Before the Golden Age, earlier writers such as E. E. Smith had ignored the light-speed barrier in writing about interstellar travel. Leinster not only worked within the constraints of the theory of relativity but also even calculated that a trip to Proxima Centauri would take seven years if the ship traveled under a constant acceleration and deceleration of one gravity. Leinster also notes that such an acceleration would bring the ship to a significant fraction of the speed of light, but he fails to take account of the resulting time dilation, which would reduce the subjective length of the trip by at least two years.

Asimov also writes, "The thing I remember most clearly over the years about 'Proxima Centauri' is the peculiar horror I felt at the thought of a race of intelligent plants that lusted after animal food. It is almost an unfailing recipe for a startling science fiction story to begin by inverting some thoroughly accepted situation, something so ordinary as to be almost disregarded. Of course, animals eat plants, and of course, animals are quick and more or less intelligent, while plants are motionless and utterly passive (except for a few insect-eating plants, which can be disregarded). But what if intelligent and carnivorous plants fed on animals, eh?"

Publication history

[edit]- Sidewise in Time, edited by Murray Leinster, Shasta, 1950

- Conquest of the Stars, Malian Press, 1952

- Monsters and Such, edited by Murray Leinster, Avon, 1959

- Before the Golden Age, edited by Isaac Asimov, Doubleday, 1974

- The Best of Murray Leinster, edited by Brian Davis, Corgi, 1976

- The Best of Murray Leinster, edited by J.J. Pierce, Del Rey, 1978

- The Road to Science Fiction 2: From Wells to Heinlein, edited by James Gunn, Mentor, 1979

- First Contacts, edited by Joe Rico, NESFA Press, 1998

References

[edit]- ^ Everett F. Bleiler, Science-Fiction: The Gernsback Years, Kent State University Press, 1998, p.248

External links

[edit]- "Proxima Centauri" title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- "Proxima Centauri" on the Internet Archive