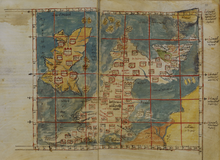

Ptolemy's map of Ireland

Ptolemy's map of Ireland is a part of his "first European map" (depicting the British Isles) in the series of maps included in his Geography, which he compiled in the second century AD in Roman Egypt and which is the oldest surviving map of Ireland. Ptolemy's own map does not survive, but is known from manuscript copies made during the Middle Ages and from the text of the Geography, which gives coordinates and place names. Ptolemy almost certainly never visited Ireland, but compiled the map based on military, trader, and traveller reports, along with his own mathematical calculations. Given the creation process, the time period involved, and the fact that the Greeks and Romans had limited contact with Ireland, it is considered remarkably accurate.

Creation of the map

[edit]The map of Ireland is included on the "first European map" sections (Ancient Greek:

Ptolemy, living thousands of miles east of Ireland in Roman Egypt, produced an interpretation of the world based on the writings available such as texts accessible in the Library of Alexandria. In 2006, R. Darcy and William Flynn described his map of Ireland as "a long exposure photograph in the sense that it most likely represents points recorded not instantaneously but over time, written down and fixed at roughly AD 100".[2]

Ireland in the Roman imperial period

[edit]Ireland (Ancient Greek: Ἰουερνία, romanized: Iouernía[1]: 142 [3] or Latin: Hibernia) was known to the Romans and may have been partially colonised by them.[2] Tacitus mentioned the island in his writings as "a small country in comparison with Britain, but larger than the islands of the Mediterranean. In soil and climate, and in the character and civilisation of its inhabitants, it is much like Britain".[4][5] Ancient remains at Stoneyford in County Kilkenny and Loughshinny in County Dublin may indicate a Roman presence at these sites.[2][6][7][8]: 254

Methodology

[edit]The work known as the Geography included guidelines on how to 'flatten' the image – or represent a 3D object on a 2D surface – of the Earth when constructing maps. Ptolemy believed in a spherical Earth within a geocentric model of the universe, and based his calculations of longitudes and latitudes on this foundational principle. Determining the obliquity of the ecliptic, the tilt of the Earth relative to the perceived movement of the Sun in the sky, his work became "the foundation of all astronomical science" in analysing the angle of the Sun during the longest day for locations on different parallels of longitude".[2]

The Geographia was not well known in the Western Roman Empire and was lost by the collapse of the empire in the late fifth century. However, there are indications it was known in the Eastern Empire. A Greek manuscript copy of the work now in the British Library was produced around 1400, and the map is oriented with south at the top.[9]

Precision

[edit]Ptolemy underestimated the length of the equator by 18% and this had an impact on all his maps. One result of this is that his latitudinal estimates are more accurate than his longitudinal ones. The reports he received would have had better directional information (towards the sunrise/sunset, at a left/right angle to the sun at noon) than on distance (five days journey from Roman Gaul).[2] The west coast is poorly represented compared to the other three, and identification of the names Ptolemy gives is speculative. This is consistent with the Romans having less contact with Irish communities in this region.

Communities identified

[edit]The peoples listed by Ptolemy as inhabiting the north coast are the Wenniknioi in the west and the Rhobogdioi in the east.

Peoples of the west coast are: the Erdinoi near Donegal Bay; the Magnatai or Nagnatai of County Mayo and Sligo; the Auteinoi between County Galway and the Shannon, identifiable with the early medieval Uaithni; the Ganganoi, also known in north Wales; and the Wellaboroi in the far south-west.

Peoples of the south coast are the Iwernoi in the west, who share their name with the island, Iwernia, and can be identified with the early medieval Érainn; the Usdiai; and the Brigantes in the east, who share their name with a people of Roman Britain.

The tribes listed on the east coast are Koriondoi; the Manapioi, possibly related to the Menapii of Gaul; the Kaukoi, probably not related to the Germanic Chauci of the Low Countries; the Eblanoi; the Woluntioi, identifiable with the early medieval Ulaid; and the Darinoi.

Place names listed

[edit]In Ireland (Ancient Greek: Ἰουερνία

Rivers and estuaries

[edit]

- mouth of the river Logia (Λογία ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Logía potamoû ekbolaí)[1]: 144 – Belfast Lough[1]: 145 (Irish: Loch Laoigh).[citation needed]

- mouth of the river Rhawiu (Ῥαουίου ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Rhoaouíou potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Ravius)[1]: 142–143 – the River Erne.[citation needed]

- mouth of the river Dur (

Δ ο ὺρ ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Doùr potamoû ekbolaí)[1]: 143 – Dingle Bay[citation needed] - mouth of the river Iernu (Ἰέρνου ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Iérnou potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Iernus)[1]: 144–145 – possibly the River Erne, although it flows into Donegal Bay, much further north,[1]: 145 so possibly the Kenmare.[citation needed]

- mouth of the river Widwa (

Ο ὐιδούα (Ο ὐδία) ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Ouidoúa (Oudía) potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Vidua (Oudia))[1]: 142–143 – the River Foyle.[citation needed] - mouth of the river Buvinda (Βουουίνδα (Βουβίνδα) ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Bououínda (Bouvínda) potamoû ekbolaí) – the River Boyne.[1]: 144–145

- mouth of the river Oboka (Ὀβόκα ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Obóka potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Oboca)[1]: 144–145 – possibly the River Liffey[1]: 145 or the River Avoca in County Wicklow.[citation needed]

- mouth of the river Modonnu (Μοδόνου (Μοδνούννου) ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Modónou (Modnoúnnou) potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Modonus (Modnunnus))[1]: 144–145 – possibly the Slaney, but more likely the Avoca.[citation needed]

- mouth of the river Ausoba (

Α ὔσοβα ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Aúsoba potamoû ekbolaí)[1]: 144 – River Corrib and Lough Corrib (Irish: Loch Oirbsean).[citation needed] - mouth of the river Argita (Ἀργίτα ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Argíta potamoû ekbolaí)[1]: 142–143 – the River Bann.[citation needed]

- mouth of the river Libniu (Λιβνίου ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Libníou potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Libnius)[1]: 144 – possibly Clew Bay.[citation needed]

- mouth of the river Senu or Sinu (Σήνου (Σίνου) ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Sḗnou (Sínou) potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Senus)[1]: 144 – probably the Shannon Estuary,[1]: 145 although placed too far to the north.

- mouth of the river Dabrona (Δαβρώνα ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Dabrṓna potamoû ekbolaí)[1]: 143 possibly the River Lee[1]: 145 or the Munster Blackwater.[citation needed]

- the mouth of the river Birgu (Βίργου ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Bírgou potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Birgus)[1]: 143 probably the River Barrow.[1]: 145

- mouth of the river Winderios (

Ο ὐινδέριος (Ἰουνδέριος) ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί, Ouindérios (Ioundérios) potamoû ekbolaí, Latin: Vinderis)[1]: 144–145 – possibly Carlingford Lough, Dundrum Bay or Strangford Lough.[citation needed]

Promontories

[edit]- Fair Head, County Antrim (Ῥοβόγδιον ἄκρον, Robógdion ákron, Latin: Robogdium)[1]: 142–143

- Carnsore Point (Ἱ

ε ρ ὸν ἄκρον, Hieròn ákron, 'Holy Cape')[1]: 144–145 - the promontory Isamnion (Ἰσάμνιον [ἄ

κ ρ ο ν ], Isámnion [ákron], Latin: Isamnium) – on the east coast.

Towns

[edit]

- Nagnata or Magnata (Νάγνατα (Μάγνατα) πόλις, Nágnata (Mágnata) pólis)[1]: 144 – a settlement of the Nagnatae or Magnatae people, possibly somewhere in County Sligo.[citation needed]

- Eblana (Ἔβλανα πόλις, Éblana pólis)[1]: 144 – later site of Dublin.[1]: 145

- Manapia (Μαναπία πόλις, Manapía pólis)[1]: 144 – a settlement of the Manapii.[10]

Towns of the interior

[edit]- Raeba (Ῥαίβα (Ῥέβα), Rhaíba (Rhéba))[1]: 144 – possibly the royal site of Cruchain[citation needed]

- Rhegia (Ῥηγία, Rhēgía) – probably the royal seat (Latin: regium) of a local prince.[1]: 144–145

- Laberos (Λάβηρος, Lábēros, Latin: Laberus)[1]: 144–145

- Makolikon (Μακόλικον, Makólikon, Latin: Macolicum)[1]: 144–145

- "a second Rhegia" (ἑτέρα Ῥηγία, hetéra Rhēgía) – probably another seat of a local prince.[1]: 146–147

- Dounon (

Δ ο ῦν ο ν , Doûnon, Latin: Dunum)[1]: 146–147 - Ivernis (Ἰουερνίς (Ἰερνίς), Iouernís (Iernís), Latin: Hibernis (Iernis))[1]: 146–147 – Cashel, County Tipperary.[citation needed]

Islands

[edit]

Besides the Irish mainland, Ptolemy names seven islands and mentions an archipelago to the north (the Inner Hebrides) which he says consists of five others. Among the islands he names to the east are the Isle of Man and Anglesey. Three others (Rhikina, Edros and Limnos) may be islands nearby Ireland or may be among the Channel Islands, since Pliny the Elder's Natural History may refer to Alderney, Guernsey, and Jersey with similar names (Riginia, Andros, and Silumnus).[1]: 147

North of Ireland

[edit]- The five Ebudes (Ἐ

β ο ῦδ α ι , Eboûdai, Latin: Eboudae), of which Ptolemy says two are themselves called Ebuda (Ἔβουδα, Ébouda) – probably the Inner Hebrides.[1]: 146–147 - Rikina or Engarikenna (Ῥικίνα (Ἐγγαρίκεννα), Rhikína (Engaríkenna), Latin: Ricinia (Engaricena)) – possibly Rathlin Island.[1]: 146–147

- Maleos or Malaïos (Μαλεός (

Μ α λ α ῖος), Maleós (Malaîos), Latin: Maleus (Malaeus)) - Epidion (Ἐπίδιον, Epídion, Latin: Epidium)

East of Ireland

[edit]- Monaoeda or Monarina (Μονάοιδα (Μοναρίνα), Monáoida (Monarína)) – Isle of Man.[1]: 146–147

- the island Mona (Μόνα

ν ῆσος, Móna nê̄sos) – Anglesey.[1]: 146–147 - the desert island Edros or Adros (Ἔδρου (Ἄ

δ ρ ο υ ) ἔρημος, Édrou (Ádrou) érēmos, Latin: Edrus (Adrus)) – possibly Howth Head.[1]: 146–147 - the desert island Limnos (Λίμνου ἔρημος, Límnou érēmos, Latin: Limnus) – possibly Lambay Island.[1]: 146–147

Legacy

[edit]

A Latin woodcut of the "first European map" published by Johann Reger in Ulm in 1486 and thought to be one of the earliest surviving printed reproductions of the map, was bought by the National Library of Wales Aberystwyth in 2008.[11][12]

Ptolemy's map of the British Isles remained the prevailing cartographic depiction of Ireland until the early modern period. A portolan chart prepared in Venice by Grazioso Benincasa in 1468 is "the first depiction of Ireland as an island in its own right, rather than as part of the British Isles".[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar Stückelberger, Alfred; Mittenhuber, Florian; Grasshoff, Gerd, eds. (2006). Klaudios Ptolemaios Handbuch der Geographie: Griechisch-Deutsch (in German). Vol. 1. Basel: Schwabe. ISBN 978-3-7965-2148-5.

- ^ a b c d e Darcy, R.; Flynn, William (March 2008). "Ptolemy's map of Ireland: a modern decoding". Irish Geography. 41 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1080/00750770801909375. ISSN 0075-0778.

- ^ Isaac, G.R. (2009). "A Note on the Name of Ireland in Irish and Welsh". Ériu. 59: 49–55. doi:10.3318/ERIU.2009.59.49. ISSN 0332-0758. JSTOR 20787545.

- ^ Waddell, John (2010). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland (3rd ed.). Dublin: Wordwell. p. 374. ISBN 9781905569472. OCLC 793459626.

- ^ "Roman contacts with Ireland | Irish Archaeology". irisharchaeology.ie. 2011-11-10. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- ^ Raftery, Barry (1994). Pagan Celtic Ireland: the Enigma of the Irish Iron Age. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-500-05072-9.

- ^ Cróinín, Dáibhí Ó (2005-02-24). A New History of Ireland, Volume I: Prehistoric and Early Ireland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-154345-6.

- ^ Edwards, Nancy (2005). "VIII: The archaeology of early medieval Ireland, c. 400–1169: settlement and economy". In Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí (ed.). A New History of Ireland: Volume I: Prehistoric and early Ireland. Oxford University Press. pp. 235–300. ISBN 9780191543456.

- ^ "Ptolemaic Map Of Ireland". British Library. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), Manapii

- ^ "National Library shares 2nd Century Ptolemy map image". BBC News. 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ "Prima Europe tabula – Map of the British Isles from Ptolemy's Geography, 1486". National Library of Wales. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Wallace, Arminta (2018-06-09). "Oldest map of Ireland puts us on the edge of the world". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2024-06-03.