Southern Crossing (California)

Southern Crossing | |

|---|---|

Map of San Francisco Bay with proposed Southern Crossing (1956 alignment) | |

| Coordinates | 37°41′38″N 122°18′44″W / 37.6938°N 122.3123°W (1954 alignment) |

| Crosses | San Francisco Bay |

| Locale | San Francisco/ Brisbane/ San Bruno and Alameda, California, U.S. |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Low-level trestle, single-tube tunnels, artificial islands, mole fill (1954 alignment) |

| Total length | 40,730 feet (12.41 km) (1954 alignment) |

| Clearance below | 15 feet (4.6 m) (crash boat, eastern section) |

| Location | |

| |

The Southern Crossing is a proposed highway structure that would span San Francisco Bay in California, somewhere south of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge and north of the San Mateo–Hayward Bridge. Several proposals have been made since 1947, varying in design and specific location, but none of them have ever been implemented because of cost, environmental and other concerns.[1][2]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]The idea for the Southern Crossing dates back to the 1940s when several additional bridges across San Francisco Bay were studied.[7] After the Bay Bridge crossing opened in 1936, connecting Rincon Hill 2 in San Francisco with the Key Mole 5 in Oakland via two high-level bridges and a tunnel through Yerba Buena Island, vehicle traffic exceeded estimates almost immediately; by 1945, even with gasoline rationing, traffic was 191% of the estimates made during planning, and would reach an average of 69,000 vehicles per day by 1946.[3]: 13 A second crossing was deemed necessary and studies were initiated to determine the best location and configuration.

First proposal (1941): Hunters Point to Bay Farm Island

[edit]A study completed on November 18, 1941 conducted by a joint Army-Navy Board[8] concluded that a high-level bridge between Hunters Point 4 and Bay Farm Island 8 was feasible at an estimated cost of $53.2M.[9]: 15 The high-level bridge was preferred to a low-level lift bridge.[4]: I-2 The western terminus would have been on the south side of the existing Hunters Point Naval Shipyard and the eastern terminus would be on the southwest shore of Bay Farm Island. However, no immediate need was identified for a new bridge, and the project was shelved.[9]: 15

Second proposals (1947): Parallel Bridge and Southern Crossing

[edit]Southern Crossing: Potrero Point to Alameda

[edit]I personally believe that both crossings are needed and should be constructed as early as possible. I believe our plans should be projected on that premise. If it were financially possible to do so I would vote for their construction simultaneously. But it cannot be done. Any new crossing must be financed by revenue bonds and the experts who pass upon such matters advise that we could not sell the bonds of two crossings at one time.

— Governor Earl Warren, Statement at the California Toll Bridge Authority Meeting, March 23, 1949[10]: 38

On January 25, 1947, another joint Army-Navy Board published a study which concluded that a combination of causeway and tube from San Francisco (near Army Street/Potrero Point 3 ) to Alameda 7 was preferred.[11][12][9]: xii From Alameda, the route would run north through the Posey Street tube to a point in Oakland near the present-day western terminus of Interstate 980.[13] This was essentially the same as alternative no. 12 from the contemporaneous California Department of Public Works (DPW) study.[4]: I-4 Both routes recommended by the two 1947 studies were endorsed by Charles H. Purcell, the director of the California DPW on November 10, 1947; however, because of limited budget, the more expensive Southern Crossing option would be built after the Parallel Bridge.[9]: xii–xiii

During the development of the Joint Army-Navy Board study, a public meeting was held on August 13, 1946, where ten alternative alignments for a second crossing were suggested. One group, based in San Francisco, advocated for a low-level causeway allowing the extension of the transcontinental rail line from Oakland; another group, based in the East Bay, proposed a high-level span for automobiles only. The California state government, represented by engineer F. W. Panhorst, agreed with the East Bay group and further advocated that to provide the maximum reduction in traffic on the Bay Bridge, the western terminus should be on Telegraph Hill 1 or Rincon Hill 2 . The August 1946 meeting was also notable for the first public presentation of the Reber Plan, which called for an immense dike between San Francisco and Oakland 2,000 feet (610 m) wide, reclaiming 180,000 acres (73,000 ha) of land from San Francisco Bay and eliminating the need for another bridge.[14] The 1947 Joint Army-Navy Board considered 29 different alignments before concluding the causeway-tube was the preferred option.[4]: I-3

Parallel Bridge

[edit]The first of the California state government studies was published a week later, on January 31, 1947, which concluded that another trans-Bay crossing was feasible and recommended that it be located close to the existing Bay Bridge.[3] This alignment was later named the Parallel Bridge.[9]: xii

The main reason to duplicate the existing route was to provide immediate relief to Bay Bridge traffic; the crossing further south from Potrero Point 3 to Alameda 7 was estimated to divert only 20% of existing traffic, and the southernmost proposal studied, from Hunters Point 4 to Bay Farm Island 8 , was estimated to divert only 5% of existing traffic.[3]: 18 The alternative western terminus at Telegraph Hill 1 was rejected on the basis of existing traffic patterns and freeway connections, and the alternative eastern terminus on the S.P. or Oakland Mole 6 was rejected not only because it would require a long high-level span to avoid interference with the existing shipping channel, but also that such a span would also interfere with flight operations at Naval Air Station Alameda.[3]: 18

The 1947 study also determined the feasibility of extending existing railroad termini for the Western Pacific Railroad, Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe, and Southern Pacific from Oakland to San Francisco; of the three, SP already had the option of using the Dumbarton Cut-off, and WP and AT&SF used buses (for passengers) or ferries (for freight); both a high-level bridge and a tunnel were ruled out as the required grades for the high-level bridge could not be achieved without excessively long approaches, and the tunnel would require conversion to electric locomotives. However, a low-level bridge accommodating rail traffic was considered for the southernmost Hunters Point 4 to Bay Farm Island 8 crossing as alternative no. 11.[3]: 20

Alternative no. 5 would have used parallel tubes on a continuous radius curve of 32,000 ft (9,800 m), providing the shortest overall distance at 31,850 ft (9,710 m). Each concrete tube would be 38 ft (12 m) in outer diameter, and would be built on land in segments, which would each be floated into position then sunk in place. Ventilation would be provided through the roadway space, connected to ventilation structures at the two termini.[3]: 104–105 A similar underwater route, with termini at the Market Street subway (slightly north of Rincon Hill) and the S.P. Mole was eventually built as the Transbay Tube for BART in the 1960s.

Alternative no. 7 included what would have been the longest suspension bridge in the world for the western portion, slightly longer than the Golden Gate Bridge at 9,600 ft (2,900 m) long overall, composed of a 4,800 ft (1,500 m) main span flanked by two 2,400 ft (730 m) side spans. Of all the alternative options studied in 1947, no. 7 had the shortest distance to span on the western portion.[3]: 106

Four true southern crossings were studied in 1947 (alternatives no. 10, 10A, 11, and 12). 10 and 10A differed in the configuration of the lower deck; 10 called for two truck lanes and two railroad tracks, while 10A omitted the tracks entirely. Both 10/10A and 12 included the cost of an additional tube to augment the existing Posey tube from Alameda to Oakland,[3]: 108–109 which was eventually constructed as the Webster Street tube in 1963. Alternative no. 11 devoted the lower deck entirely to four railroad tracks, as the anticipated vehicular traffic was low. It included a 500 ft (150 m) long vertical lift span.[3]: 110 Alternative no. 12 would use four tunnels on the western half, each containing two lanes of traffic, approximately 6,800 ft (2,100 m) long overall to provide a wide navigation channel; the eastern portion of the crossing would be at the water's level, consisting of a trestle 6,700 ft (2,000 m) long and a mole 13,500 ft (4,100 m) long.[3]: 111

| No. | Western terminus | via | Eastern terminus | Structure | Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West | East | |||||

| 2 | Telegraph Hill 1 | Yerba Buena Island | Key Mole 5 | Four-span suspension bridge | Truss/cantilever bridge | $103M |

| 3 | S.P. Mole 6 | $102M | ||||

| 4 | Key Mole 5 | $105.4M | ||||

| 5 | Rincon Hill 2 | — | S.P. Mole 6 | Two or more tubes | $167M | |

| 6 | Telegraph Hill 1 | Yerba Buena Island | S.P. Mole 6 | Four-span suspension bridge | Truss/cantilever bridge | $101M |

| 7 | Key Mole 5 | Three or four-span suspension bridge | $134M | |||

| 8 | Rincon Hill 2 | Key Mole 5 | Twin of existing Bay Bridge, 300 feet (91 m) to the north | $84M | ||

| 9 | S.P. Mole 6 | Twin of existing western span | Truss/cantilever bridge | $103M | ||

| 10 | Potrero Pt 3 | — | Alameda 7 | Truss/cantilever bridge | $108M | |

| 10A | $83M | |||||

| 11 | Candlestick Pt 4 | Bay Farm Island 8 | Steel with lift across channel | $130M | ||

| 12 | Potrero Pt 3 | Alameda 7 | Mole, viaduct, and tube | $137M | ||

The California Department of Public Works created the San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings Division in December 1947 to study the Parallel Bridge and Southern Crossing proposals in further detail.[4]: I-4 In 1948, the Toll Crossings Division reiterated that a southern crossing was "entirely feasible" but recommended the expansion of the existing Bay Bridge with the Parallel Bridge alignment instead, which could be completed in 1954 at an estimated cost of US$155,000,000 (equivalent to $1,965,600,000 in 2023).[15] Preliminary plans for both the Parallel Bridge and Southern Crossing were prepared in 1948, which were reviewed by a board of consulting engineers in 1949.[10]: 2–3

Because both bridges could not be financed simultaneously, the California Toll Bridge Authority resolved to complete the plans for the Parallel Bridge on March 23, 1949.[10]: 3–4 Local and state leaders failed to align their support on a single proposal. In May 1949, San Francisco mayor Elmer Robinson testified before the California State Assembly in support of the Southern Crossing.[16] Director Purcell went before Congress in July 1949 to request permission to expand the right-of-way on Yerba Buena Island to allow construction of the Parallel Bridge.[10]: 3–4 Work on both the Southern Crossing and Parallel Bridge projects was halted on June 30, 1950, after disputes about the priority, alignment, and purpose of a second bridge could not be reconciled. An attempt to revive a second trans-Bay crossing failed to pass the California State Legislature during the 1951 session.[4]: I-5

Third proposal (1949, 1989, 1999): Wright/Polivka Butterfly Wing bridge

[edit]At about the same time, architect Frank Lloyd Wright and engineer Jaroslav Joseph Polivka unveiled the reinforced concrete "Butterfly Wing" bridge in May 1949 before Bay Toll Crossings.[17] The Butterfly Wing bridge was first presented to the public in May 1953 before a sold-out audience at the San Francisco Museum of Art.[18] A 16 ft (4.9 m) long model of the Butterfly Wing bridge was built for the 1953 presentation;[18] it was later displayed locally in shops,[19] malls,[20] and was included in a traveling exhibition[21] before being used as a prop in the 1988 film Die Hard.[22]

Polivka had previously submitted preliminary plans to DPW for a Southern Crossing bridge in February 1947; his initial design featured an immense 3,200-foot (980 m) long concrete arch spanning the navigation channel, which was unprecedented in length, size, and material.[23] Polivka is credited with piquing Wright's interest in bridge design; they began their collaboration later in 1947, resulting in the Butterfly Wing bridge proposal for the Southern Crossing.[24][25]: 748 The Butterfly Wing design was derived from a crossing designed by Wright in 1947 over the Wisconsin River near Spring Green, Wisconsin for the Wisconsin Highway commission.[21]

The final design carries six lanes of traffic over twin 2,000-foot (610 m) long diverging arches providing 200 feet (61 m) of vertical clearance above the bay's main ship channel.[26] Another source claims the pair of main arches were 1,000 feet (300 m) long and afforded 175 feet (53 m) of vertical clearance.[25]: 750–752 The concrete "tap-root" piers were hollow to add buoyant support to the structure.[23] The original alignment had a western terminus near Third and Army 3 and an eastern terminus on Bay Farm Island 8 .[27] The design included a hanging park and parking in the middle of the arched section, making the Butterfly Bridge a destination in addition to a crossing.[22] Polivka and Wright's design, using reinforced concrete, was designed to be half the cost of a conventional steel bridge, provide lower maintenance costs, and resist earthquake damage.[28] However, such proposals never got beyond the drawing board because of cost concerns.[13][29]

The Butterfly Wing bridge design has been revived occasionally since it was first announced; in 1989, the Oakland Museum of California exhibited the bridge drawings and model,[24] and that year, Aaron Green and T. Y. Lin proposed the Wright/Polivka design should be built between San Bruno 12 (western terminus at the junction of I-380 and the Bayshore Freeway) and San Lorenzo 11 (terminating into Hwy 238), carrying eight lanes of traffic and BART tracks.[30] In 1999, the Butterfly Wing design was again promoted, this time as a candidate design for the eastern span replacement of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge,[31] winning Oakland mayor Jerry Brown's support, although by that time, the design had already missed the deadline for replacement proposals, which had been during a three-day workshop held in 1997.[24]

Fourth proposal (1953–58): Potrero Point to Bay Farm Island

[edit]

In 1953, the legislature passed a bill to build the Southern Crossing[32] with the alignment spanning from San Francisco near Third and Army Streets (Potrero Point 3 )to near Bay Farm Island 8 in Alameda.[7][13] The western approaches would include connections to the Bayshore Freeway at 26th Street; the Southern Crossing would also connect with a proposed future freeway at Army Street and an extended Embarcadero Freeway.[4]: § V At the eastern end, the southern crossing would connect to the Alameda County road along the bayfront near its intersection with Kilkenny Road.[4]: § VI [32] The Southern Crossing alignment specified by the legislature had not been previously studied in the 1941 and 1947 reports.[4]: I-6

After the Southern Crossing Bill was passed, at a public hearing held on August 17, 1953, the Navy announced plans to extend its seadrome runways south from NAS Alameda, which would interfere with the planned direct alignment of the Southern Crossing, and the Department of the Army subsequently denied the Southern Crossing application on November 3, 1953.[4]: I-6 A revised alignment was designed to route around the restricted area, and the Army granted a construction permit on April 8, 1954,[4]: I-7 contingent on the construction to start within five years and complete within ten.[4]: Append-11

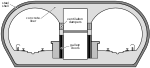

In the 1954 Progress Report, the approved design for the Southern Crossing was largely a low-level causeway not to exceed 40 feet (12 m) in height to avoid seadrome interference, although the eastern approach would provide a vertical clearance of 15 feet (4.6 m) to allow the passage of crash boats from NAS Alameda. A tube section would be built across the navigation channel to allow the passage of ships deeper into the Bay. Traffic would be carried in six lanes, divided into two three-lane causeways and three two-lane tubes, and grades would be limited to 31⁄2%. The total planned length of the 1954 Southern Crossing was 40,730 feet (12,410 m).[4]: IV-1, 2

| Structure | Image | Length | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Viaduct |

|

5,288 ft 1,612 m |

Reinforced concrete spans supported by reinforced concrete piles. Two roadways, each 38 ft (12 m) wide and with three unidirectional lanes. |

| West Transition | 813 ft 248 m |

Transition (from viaduct to tube) and ventilation structures to be built on artificial sand islands. | |

| West Ventilation |

|

75 ft 23 m | |

| Bay Tube |

|

5,808 ft 1,770 m |

Navigation channel is 1,500 ft (460 m) wide allowing a minimum draft of 50 ft (15 m). Tubes set in dredged trench; trench would be 7,700 ft (2,300 m) long, 60 to 70 ft (18 to 21 m) deep, and 140 to 350 ft (43 to 107 m) wide. Cylindrical tube sections each 200.25 ft (61.04 m) long to be fabricated on land, towed into position, sunk into trench, and covered with sand. Tube sections would be 37 ft (11 m) (outer diameter) and 32 ft (9.8 m) (inner diameter), each weighing 5,253 short tons (4,765 t). Fresh air supplied from ventilation structures to duct under roadway; duct above roadway used for exhaust. |

| East Ventilation |

|

75 ft 23 m |

Transition (from tube to viaduct) and ventilation structures to be built on artificial sand islands. |

| East Transition | 813 ft 248 m | ||

| East Viaduct | 21,856 ft 6,662 m |

Reinforced concrete spans supported by reinforced concrete piles. Two roadways, each 38 ft (12 m) wide and with three unidirectional lanes. Maximum elevation 22 ft (6.7 m) above mean sea level to accommodate crash boat channel. | |

| Mole and Toll Plaza |

|

6,002 ft 1,829 m |

Two parallel 36 ft (11 m) wide roadways separated by 6 ft (1.8 m) wide median. Eight toll lanes provided for toll plaza to be built offshore from Bay Farm Island. |

According to the 1955 Progress Report, the preliminary plans had been completed and updated cost estimates were available.[33] In March 1956, the 1955 Supplement report was issued covering the legislative amendments made that month changing the San Francisco approaches to the Southern Crossing.[34][35][36]

The Southern Crossing design was updated again in October 1956; the 1956 Progress Report detailed further changes to the San Francisco and Bay Farm Island approaches mandated by legislative action.[37][38][39] By 1956, the Southern Crossing was ready to post requests for bidding; because there was "considerable opposition to raising tolls on the Bay Bridge" from their current US$0.25 (equivalent to $2.8 in 2023), the cost of the Southern Crossing meant the project would have to be built in stages.[39]: I-3 The overall length of the Southern Crossing was reduced slightly to 39,910 feet (12,160 m) with the revised approaches, but retained the same basic structure: two three-lane roadways carried on mole and viaducts, with a three-tube (each with two unidirectional lanes) section crossing the navigation channel.[39]: II-2 In San Francisco, the northern approach would connect with the Embarcadero Freeway; the southern approach would connect with the Southern Freeway, and the direct connection with the Bayshore Freeway was dropped. Both approaches would be double-decked, with three unidirectional lanes per deck.[39]: II-4 On Bay Farm Island, the Southern Crossing would split into two separate approaches at the Bay Farm Island Bridge; the two would then would connect with the Eastshore Freeway and the Posey and Webster Street tubes.[39]: II-5 In addition, the 1956 Progress Report considered the effect of the Southern Crossing on traffic over the San Mateo–Hayward Bridge (acquired by the State of California in September 1951) as well as the planned Transbay Tube.[39]: § VIII

To explore the financial feasibility further, DPW commissioned a study from Smith Barney & Co., which concluded "the Complete Southern Crossing is not feasible as presently authorized at a basic toll rate of 25 cents for both the Bay Bridge and the Southern Crossing"; the California Toll Bridge Authority then directed Bay Toll Crossings to develop a Minimum Southern Crossing plan.[40]: I-1, 2 One key statute passed in the 1957 session imposed a July 1, 1958 deadline; if funding was not finalized for the Southern Crossing by then, the project would be dissolved.[41] Another authorized funds for the construction of the Webster Street Tube without tying it to the larger Southern Crossing project.[42] Under the Minimum Southern Crossing plan of 1957, the same general alignment and design was retained, but the approaches were pruned back to a single interchange near Third and Army in San Francisco and a connection to the Bay Farm Island Bridge in the East Bay.[40]: II-1, 2

In May 1958, the Southern Crossing project was defunded and abandoned;[43] plans made to expand the capacity of existing crossings (plans completed in March 1957 to remove the Key System tracks on the lower deck of the Bay Bridge; additionally, plans completed in October 1958 to double the capacity of the San Mateo Bridge) meant a second crossing was no longer needed. In addition, by this time, plans for the Transbay Tube for public transit service across the Bay had been sufficiently developed to forecast relief for Bay Bridge traffic.[44]: § II

Fifth proposal (1962–72): Southern alignments

[edit]Three-way bridge and San Mateo County

[edit]

Yet another alternative alignment, proposed in the November 1962 Trans-bay Traffic Study, would connect India Basin 9 to both Alameda 7 and Bay Farm Island 8 ; the bridge would run to a mid-Bay junction off the southern shore of Alameda and then fork north and east, respectively. The 1962 study also included a more southern alternative alignment between Sierra Point 10 and Roberts Landing 11 in San Lorenzo, the first Southern Crossing proposal to include a terminus in San Mateo County. Subsequent public hearings, held in 1964 and 1965, showed strong popular support for both of the two proposed routes, with home geography dictating which route was favored,[5]: 4–5 and in 1965, the legislature authorized a study to compare the two alternatives as well as ferry service.[45] The results of that study were published in the 1966 Southern Crossing of San Francisco Bay report.[5]

For the India Basin–Alameda–Bay Farm Island alternative, the main navigation channel off Hunters Point would be spanned by either a high-level bridge (providing at least 220 ft (67 m) of vertical clearance) or a subsurface tube (allowing at least 50 ft (15 m) of draft). On the western end, the approach would connect to a proposed Hunters Point Freeway which would run north-south to the east of the existing Bayshore Freeway. The eastern approach would split into two at the toll plaza, located approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) offshore from Alameda; the northerly leg would continue to a new set of tubes parallel to the existing Posey and Webster Street tubes, while the easterly leg would continue to Davis Street in San Leandro.[5]: 14–29 The estimated cost of this alignment would range between $300.8 million (bridge) to $397.1 million (tunnel), depending on the option chosen to cross the navigation channel.[5]: 36–37

The Sierra Point–Roberts Landing alternative was first proposed in 1959; the total length of approximately 12.5 mi (20.1 km) would be low-level trestle or earthen barrier, with a high-level bridge over the navigation channel, similar to the second San Mateo–Hayward Bridge. The earthen barrier option was a variant of the Reber Plan, calling for a series of locks to preserve a navigation channel south, but otherwise allowing residential development on Bay fill south of the barrier.[5]: 40–55 The total estimated cost of this alignment ranged between $209.7 million (trestle) to $352.6 million (barrier).[5]: 60–61

Of the two alignments, the India Basin–Alameda–Bay Farm Island option was expected to have the greatest relief for Bay Bridge traffic and was recommended in the 1966 study report. Under the contemporary rules, the amount of money diverted from toll revenues to fund BART meant that construction of either alternative would be delayed to 1968; if the diversion was increased from $133 million to $178 million, however, the Southern Crossing would be delayed or potentially unfeasible. The earthen barrier option of the Sierra Point–Roberts Landing alignment was ruled out as the economic benefits would not justify the additional cost.[5]: 104–106

India Basin–Alameda–Bay Farm Island

[edit]

The Hunters Point/India Basin–Alameda–Bay Farm Island alignment was ultimately selected in April 1966[46]: 21 with a cable-stayed girder bridge over the main channel using an orthotropic deck.[47] The design of the channel span was directed by the noted local architect William Stephen Allen, designed to harmonize with the neighboring Bay and San Mateo bridges.[46]: 13 The Bay Conservation and Development Commission granted permits for construction of the Southern Crossing on November 6, 1969.[46]: 21

Opposition to the Southern Crossing was led by the Sierra Club and notable local politicians, including state senator George Moscone; Assemblymembers Willie Brown, John Burton, John Foran, and Leo McCarthy; and Supervisors Dianne Feinstein, Terry Francois, Robert E. Gonzalez, Robert H. Mendelsohn, and Ron Pelosi.[48] In San Francisco, Francois and Gonzalez argued the estimated $500 million cost of the Southern Crossing project would be better spent on rapid transit, and Mendelsohn and Pelosi introduced a resolution to require the project to evaluate its impact on BART.[49] Support for the Southern Crossing was largely from legislators representing districts outside the Bay Area; local polls from early 1972 showed that nearly two-thirds of Bay Area residents opposed the Southern Crossing.[50]

The scheduled start of construction was delayed until late 1971, and the anticipated completion date was 1975. Because of its potential to siphon riders (and revenue) away from the nascent BART system, the California State Assembly ordered the Toll Bridge Authority to reconsider the Southern Crossing in 1970.[47] In February 1971, the Toll Bridge Authority concluded in a report published after holding two public meetings in San Francisco and Oakland that "It is in the public interest to begin construction on this needed facility [the Southern Crossing] as soon as possible."[46] At the Oakland meeting, held the preceding December, chief engineer E. R. "Mike" Foley of the Toll Bridge Authority argued the Southern Crossing was needed to support cargo traffic and to relieve congestion on the Bay Bridge, but local politicians opposing the new bridge cited pollution concerns and the possibility of increased traffic jams due to induced demand.[51]

The 1971 report concluded that BART revenues would be minimally affected, as the Southern Crossing would provide access to southern San Francisco and northern San Mateo County, while BART would serve downtown San Francisco instead.[46]: 7 At the time, the Bay Bridge was operating at well over its designed capacity, serving 165,000 vehicles per day, on average. BART was anticipated to divert 10% of existing traffic to provide some relief, but by 1980, it was projected the Bay Bridge would see 190,000 vehicles per day while BART would move 143,000 trans-Bay commuters daily. If the Southern Crossing had been built, it was projected that in 1980, Bay Bridge traffic would be reduced to 148,000 vehicles per day, the Transbay Tube would serve 138,000 daily commuters, and the Southern Crossing would be operating at 105,000 vehicles per day.[46]: 4–5

In March 1971, Assemblymember Robert W. Crown (D-Alameda) sponsored AB 151, which would give the final decision to proceed with the construction to the legislature, taking that choice away from Bay Toll Crossings.[52] Although it passed both houses with overwhelming majorities, AB 151 was vetoed by Governor Ronald Reagan,[53] who stated the citizens of the Bay Area should be allowed to vote for the approval of the Southern Crossing directly.[54] The Assembly was unable to override the veto,[55] and two regional measures were put on the ballot for six Bay Area counties in the June 6, 1972 election: one that would give the final approval for the Southern Crossing to the legislature,[56] which voters approved,[57] and another (Proposition A) which would issue bonds to fund the Southern Crossing, which was defeated.[58][59]

Sixth proposal (1989–91): San Bruno/San Leandro

[edit]

In 1989, State Senator Quentin L. Kopp introduced Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 20, which funded a study to analyze the need for another crossing option (whether tunnel, bridge, or ferry) between Alameda County and San Francisco or San Mateo County.[60] The resulting Bay Crossings Study was published by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) in 1991 and the scope was not limited to an automobile bridge; the eleven alternatives studied were:[61]

- High-Speed Ferry and Operational Upgrade

- Southern Crossing Bridge

- Southern Crossing tunnel

- Interstate 380 to I-238 bridge (with BART)

- Interstate 380 to I-238 tunnel (with BART)

- BART SFO/OAK airport connection

- BART Alameda to Candlestick connection

- New BART Transbay Tube

- Airport people-mover connection

- Railroad Airport connection

- Intercity rail connection

Of these, the 1991 Bay Crossings Study evaluated five: alternatives 1, 4, 6, 8, and 11.[61] The proposed alignment for a new Mid-Bay Bridge (Alternative 4) ran between San Bruno 12 and San Leandro 11 ; two variants of Alternative 4 were studied in 1991, one with four lanes and another with eight lanes and BART tracks. The narrow four-lane bridge was estimated to cost $2 billion.[62] The eight-lane bridge was estimated to cost the most out of all the alternatives studied ($4 B), but would carry the greatest number of trips, providing the most relief to Bay Bridge traffic.[61]

This Southern Crossing initiative eventually died after facing opposition from environmental groups.[58]

Later proposals (2000+)

[edit]U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein revived the Southern Crossing proposal in 2000, writing a letter to California Governor Gray Davis that a study of an alternative bay crossing "must be undertaken promptly", citing projections of growing traffic congestion.[58] After two years, MTC published the 2002 San Francisco Bay Crossings Study, an update to the prior 1991 study;[6] in it, MTC concluded that a Mid-Bay Bridge between Interstate 238 in Hayward and Interstate 380 in San Bruno would cost up to US$8.2 billion to build.[1][6]: 42 Other alternatives that were studied in this period included a second Transbay Tube, widening the San Mateo–Hayward Bridge to eight lanes, and Dumbarton Rail Corridor service; of these, the Mid-Bay Bridge proved to be the most polarizing, the second Tube was the costliest, and Dumbarton Rail was called "one of the least expensive and most cost-effective of the transbay improvements studied."[6]: 2 Several alternatives were screened out during preliminary evaluations as unfeasible, including a road and rail bridge between I-238 and Candlestick Point, a Mid-Bay BART tube, and a SFO—OAK airport rail shuttle.[6]: 24

The idea was then shelved until 2010 when the Bay Area Toll Authority voted to spend up to US$400,000 to update the 2002 study.[63] The resulting San Francisco Bay Crossings Study Update (2012) concluded that due to increased costs no new trans-Bay crossings were feasible. The Mid-Bay Bridge was estimated to cost $12.4 billion, improvements to the San Mateo–Hayward and Dumbarton bridges were estimated at $2.9 billion each, and a second BART tube would cost from $8.2 to $11.2 billion, depending on the alignment.[64]: 2–4

In December 2017, in a letter to the MTC, Feinstein, along with Congressman Mark DeSaulnier, called yet again for a new span across the Bay.[65]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Cabanatuan, Michael (April 3, 2002). "New bridge? Yeah, right: Southern Crossing, transbay tube would cost at least $8 billion, study says". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (November 9, 2010). "Fresh study possible on transbay crossing". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Department of Public Works (January 31, 1947). Report to the California Toll Bridge Authority, covering preliminary studies for an additional bridge between San Francisco and the East Bay Metropolitan Area (Report). California State Printing Office. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Raab, N. C. (December 1954). A Progress Report to Department of Public Works on a Southern Crossing of San Francisco Bay (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Southern Crossing Of San Francisco Bay: India Basin-Alameda & Sierra Point-Roberts Landing Alignment Studies (Report). Division of Bay Toll Crossings, California Department of Public Works. February 1966. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e San Francisco Bay Crossings Study (PDF) (Report). Metropolitan Transportation Commission. July 2002. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ a b "Bridging the Bay: Unbuilt Projects: Additional Crossings". University of California, Berkeley Libraries. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ H.R. 158

- ^ a b c d e Tudor, Ralph A. (November 1948). A report to Department of Public Works on additional toll crossings of San Francisco Bay (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Summary of information on the proposal to build a parallel bridge across San Francisco Bay (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. July 1949. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ H.R. 529

- ^ Report of Joint Army-Navy Board on an additional crossing of San Francisco Bay (Report). Joint Army-Navy Board. 1947. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c Martin, Jim. "A Proposed "Southern Crossing" for San Francisco Bay". American Society of Civil Engineers. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ "Debate Site New Bridge Across Bay". Madera Tribune. August 13, 1946. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ "Hearing Slated On Proposed New Bay Bridge Plan". Madera Tribune. U.P. November 17, 1948. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Robinson, Elmer E (May 7, 1949). The Case for the Southern Crossing (Report). City & County of San Francisco. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Turner, Paul Venable (2016). "A Butterfly Bridge for the Bay". Frank Lloyd Wright and San Francisco. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 87–96. ISBN 978-0-300-21502-1. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ a b "Wright Terms Northbay Bridge An "Eyesore" and "Anachronism"". Mill Valley Record. May 2, 1953. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ "Model of the Frank Lloyd Wright-J.J. Polivka "Butterfly Wing Bridge" on display in the Emporium department store in San Francisco". J.J. Polivka papers, State University of New York at Buffalo. 1953. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Myrow, Rachael (January 25, 2018). "The Beautiful Bay Bridge Frank Lloyd Wright Never Got to Build". KQED News. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ a b "Frank Lloyd Wright Projects: Butterfly-Wing Bridge". The Wright Library. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Hartlaub, Peter (May 23, 2015). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Butterfly Bridge plan would have transformed San Francisco". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Weinstein, Dave (Summer 2013). "Visionaries on the Wing: As the Bay Bridge reopening nears, lost in the hoopla is Frank Lloyd Wright's forsaken 'Butterfly' design—the most beautiful span of all". Modern Living Today. Eichler Network. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c Hendricks, Tyche (March 7, 1999). "Bridge with the Wright Stuff". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Cleary, Richard (March–April 2006). Lessons in Tenuity: Frank Lloyd Wright's Bridges (PDF). Second International Congress on Construction History. University of Cambridge. pp. 741–758. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "Bridging the Bay: Bridges That Never Were". University of California, Berkeley Libraries. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ ""Butterfly Bridge": The Southern Crossing". Aaron G. Green Associates, Inc. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Muskat, Barry (November–December 2000). "In Wright's Shadow: The Legacy of Jaroslav Polivka". Buffalo Spree. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Moffitt, Mike (June 12, 2019). "Why no one has approved a second Bay bridge for 70 years". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Grieve, Tim (June 29, 1989). "New commuter gimmick — Butterfly Wing: Span designed by Frank Lloyd Wright could ease region congestion". San Bernardino Sun. McClatchy News Service. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd (1999). "Butterfly-Wing Bridge" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Commission. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ a b California State Assembly. "An act to repeal Sections 30605, 30606, 30607, and 30608 of the Streets and Highways Code, to amend Section 100.7 thereof, and to add Sections 30605 and 30607 and Article 2 to Chapter 2 of Division 17 of said code, relating to toll crossings of San Francisco Bay, including approaches thereto, and the expenses of maintaining, operating, and insuring such crossings, and providing for studies of an additional crossing". 1953 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 1056 p. 2525.

The authority and the department shall apply promptly to the appropriate officials of the Federal Government for permission to construct a southern crossing having its westerly terminus in the vicinity of Third and Army Streets in the City and County of San Francisco and its easterly terminus on Bay Farm Island, and shall obtain the necessary permits therefor as promptly as feasible.

direct URL - ^ Raab, N. C. (December 1955). Report to Department of Public Works on the Southern Crossing of San Francisco Bay (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to amend Sections 30350, 30652, and 30654 of, and to add Sections 30608, 30654.5, and 30659 to, the Streets and Highways Code, relating to toll bridges and other toll highway crossings, declaring the urgency thereof and providing that this act shall take effect immediately". 1955 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 304 p. 754. direct URL

- ^ Raab, N. C. (March 1956). A Supplement to the Report of December 1955 to Department of Public Works on the Southern Crossing of San Francisco Bay, Covering Proposed Approach Amendments to Assembly Bill No. 3249 as Outlined in Assembly Journal for March 23, 1955, at Page 1704 (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. Retrieved July 5, 2019. (this version has the full text, but omits the figures)

- ^ Raab, N. C. (March 1956). A Supplement to the Report of December 1955 to Department of Public Works on the Southern Crossing of San Francisco Bay, Covering Proposed Approach Amendments to Assembly Bill No. 3249 as Outlined in Assembly Journal for March 23, 1955, at Page 1704 (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. Retrieved July 5, 2019. (this version reproduces the figures, but omits Part I of the text)

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to add Section 30354.5 to the Streets and Highways Code, relating to toll bridges across San Francisco Bay acquired or constructed pursuant to the California Toll Bridge Authority Act, declaring the urgency thereof, to take effect immediately". 1956 Session of the Legislature, 1st extraordinary session. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 40 p. 381. Chapter 40, direct URL

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to amend Sections 30654 and 30657 of the Streets and Highways Code, relating to toll bridges and other toll highway crossings". 1956 Session of the Legislature, 1st extraordinary session. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 67 p. 459. Chapter 67, direct URL

- ^ a b c d e f Raab, N. C. (October 1956). A Report to the Department of Public Works on the Southern Crossing of San Francisco Bay (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Raab, N. C. (December 1957). A Report to the Department of Public Works on the Southern Crossing of San Francisco Bay (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to add Sections 30609 and 30660 to the Streets and Highways Code, relating to crossings of San Francisco Bay, declaring the urgency thereof, and providing that this act shall take effect immediately". 1957 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 2316 p. 4030. Chapter 2316, direct URL

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to amend Section 30657 of the Streets and Highways Code, relating to San Francisco Bay crossings". 1957 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 866 p. 2079. Chapter 866, direct URL

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act making funds available for surveys and studies of an additional San Francisco Bay crossing". 1958 Session of the Legislature, 2d extraordinary session. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 3 p. 584. direct URL

- ^ Raab, N. C. (January 1959). A Report to the Department of Public Works on the Studies of Southern Crossings of San Francisco Bay (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, Department of Public Works, State of California. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act providing for preliminary studies of a toll crossing of, or the use of surface craft for the crossing of, San Francisco Bay, making an appropriation therefor, and declaring the urgency thereof, to take effect immediately". 1965 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 970 p. 2588. direct URL

- ^ a b c d e f Van Camp, Brian R. (February 1971). Southern Crossing of San Francisco Bay: Comprehensive Review Requested by Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 26, Chapter 211, Statutes 1970 (Report). California Toll Bridge Authority of the State of California. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ a b California State Assembly. "Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 26—Relative to the southern crossing". 1970 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California (Resolution). State of California. Ch. 211 p. 3811. direct URL

- ^ "Southern crossing protest". The Potrero View. Vol. 2, no. 1. January 1, 1971. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Southern Crossing meets growing opposition". The Potrero View. Vol. 2, no. 2. February 1, 1971. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Southern span yes or no?". The Potrero View. Vol. 3, no. 6. June 1, 1972. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Proponents Claim Southern Crossing Would Aid BART". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. December 15, 1970. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Bridge Authority faces challenge". The Potrero View. Vol. 2, no. 3. March 1, 1971. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Summary Digest of Statutes Enacted and Resolutions Adopted Including Proposed Constitutional Amendments and 1969–1971 Statutory Record" (PDF). California Legislature. 1971. p. 317. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Bridge Bill Vetoed By Governor". Desert Sun. UPI. April 3, 1971. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Reagan Winner: Democrats Unable To Override Veto". Desert Sun. UPI. April 23, 1971. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "73 Per Cent Vote Turnout Due For State". Desert Sun. UPI. June 6, 1972. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Proposition Nine Loses By 2-1; All Others Pass". Desert Sun. UPI. June 7, 1972. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c Matier, Phillip; Ross, Andrew (January 19, 2000). "Feinstein Pushes for Southern Crossing". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ "No on A". Sierra Club. 1972. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ California State Assembly. "Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 20—Relative to a San Francisco Bay crossing study". 1989–1990 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California (Resolution). State of California. Ch. 168 p. 7037. direct URL

- ^ a b c "Bay Crossings Study". Metropolitan Transportation Commission. 1991. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (January 20, 2000). "Southern Crossing: Boulevard of Broken Dreams". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "New Bay Bridge from San Lorenzo? 'Southern Crossing' span back on planners' study plate". Pleasanton Weekly News. November 10, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ AECOM (May 2012). San Francisco Bay Crossings Study Update (PDF) (Report). Metropolitan Transportation Commission. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ Daniel Borenstein (December 7, 2017). "Feinstein calls for new bridge across the bay". The Mercury News. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

External links

[edit]Butterfly Wing bridge

[edit]- Polivka, Jaroslav (April 2018). "Heritage Auction #5355, Lot #6060: Blueprints for Frank Lloyd Wright's San Francisco Bay Bridge, dated 1949". Heritage Auctions. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- "Model Of The Butterfly Bridge". British Pathé. 1953. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- Kohlstedt, Kurt (March 16, 2018). "The Butterfly Bridge: Wright's Unbuilt Bay Crossing for Cars & Pedestrians". 99% Invisible. Retrieved July 11, 2019.