The Chumscrubber

| The Chumscrubber | |

|---|---|

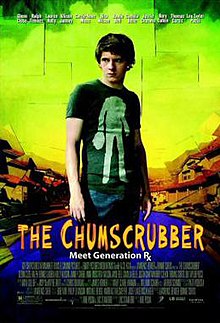

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Arie Posin |

| Screenplay by | Zac Stanford |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Lawrence Sher |

| Edited by | Arthur Schmidt |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[4] |

| Box office | $351,401[5] |

The Chumscrubber (German: Glück in kleinen Dosen) is a 2005 comedy-drama film, directed by Arie Posin, starring an ensemble cast led by Jamie Bell as the main protagonist, and Justin Chatwin as the central antagonist.[6] The plot, written by Posin and Zac Stanford, focuses on the chain of events that follow the suicide of a teenage drug dealer in an idealistic but superficial town. Some of the themes addressed in the film are the lack of communication between teenagers and their parents and the inauthenticity of suburbia. The titular Chumscrubber is a character in a fictional video game that represents the town and its inhabitants.

Posin and Stanford had originally planned to shoot the film using their own funds, but they sent the script to producers Lawrence Bender and Bonnie Curtis who agreed to produce the film and help to raise the budget. Bell was cast in the lead role after an extensive auditioning process, and the film was shot in various California locations over 30 days in April 2004.

The Chumscrubber premiered at the Sundance Film Festival on January 25, 2005 and was released theatrically on August 26, 2005. An accompanying soundtrack, composed mostly by James Horner, was released on October 18, 2005. The film was both a critical and commercial disappointment as it received mixed-to-negative reviews and earning back only US$351,401 of its $10 million budget.

Plot

[edit]Troy Johnson, the supplier of prescription drugs to fellow high school students in the fictional southern California town of Hillside, commits suicide. Troy's best friend Dean Stiffle finds his dead body but does not show any emotion about the loss of his friend. Dean is prescribed antidepressants by his psychiatrist father Bill to help "even him out". When Dean returns to school, he is antagonized by drug dealers Billy and Lee, who were supplied by Troy. Their friend, Crystal Falls flirts with Dean, but he soon realizes that her true intentions are for Dean to retrieve the remaining drugs in Troy's home, and he refuses to cooperate. To force Dean to procure the drugs, Billy and Lee plan to kidnap Dean's younger brother, Charlie as ransom, but instead they mistakenly kidnap another boy, Charlie Bratley.

The kidnappers hold Charlie Bratley overnight at Crystal's home. Bratley's parents are unaware that he is even missing. Dean eventually agrees to go to Troy's house to find the drugs. Upon delivery, Billy discovers that the bag does not contain the prescription drugs and starts a fight with Dean, leading to Dean's arrest. While trying to explain everything to Officer Lou Bratley, Charlie's father, Dean reveals that his brother Charlie replaced the drugs with a bag of the vitamins that their mother Allie sells. Neither Officer Bratley nor Dean's father believes his story, but he is released, whereupon his father increases his dosage of antidepressants. Meanwhile, Charlie Stiffle crushes the real drugs and intentionally puts them into a casserole that his mother made for Troy's memorial.

The next day is Troy's memorial service and the wedding of Mayor Michael Ebbs to Charlie Bratley's mother Terri. Lou finally realizes that his son actually has been kidnapped and begins to look for him. At Lee's house, Crystal asks Lee to help stop the kidnapping scheme, but he does not comply. Crystal goes to Dean's house for help, where she finds him hallucinating about Troy's death and finally expressing his grief. Meanwhile, a paranoid Lee, encouraged by Billy, tries to kill Charlie Bratley to avoid being caught, but Charlie fights back and slices the knife through Billy's eye. Billy runs out into the street, screaming in pain, and is hit by Lou's police car.

Dean attends Troy's memorial, where all of the visitors are intoxicated by the drugs that are in his mother's casserole. Troy's mother, Carrie discloses to Dean that she never knew her son. Dean tells her about Troy and acknowledges that they were best friends, and she thanks him. Billy is later sent to prison, where he quickly becomes a punk to much larger inmates. Lee, who successfully changes the narrative of his involvement during the trial, is acquitted. A closing voiceover explains that Dean and Crystal "escape together", and they are shown kissing.

Cast

[edit]

- Jamie Bell as Dean Stiffle, a teenage outsider and the film's protagonist. He refuses to face his grief over his best friend's suicide, instead choosing to numb his feelings with drugs.

- Camilla Belle as Crystal Falls, Dean's rebellious classmate. Unlike her friends, she feels sympathy for Dean and is reluctant to partake in the plans to kidnap his brother.

- Justin Chatwin as Billy Peck, a drug dealer at Dean's high school who was formerly supplied by Troy. He dreams to join the air force after graduation, but his fight with Charlie Bratley leaves him with impaired vision.

- Lou Taylor Pucci as Lee Parker, Billy's smart but timid friend who often succumbs to peer pressure. His parents pressure him about his schoolwork, hoping for him to get into a good college.

- Rory Culkin as Charlie Stiffle, Dean's younger brother. He spends most of his time on the family couch playing video games.

- Thomas Curtis as Charlie Bratley, the 13-year-old son of Officer Lou Bratley and his ex-wife Terri. Having been largely ignored by his negligent mother, at the end of the film he is sent to live with Lou.

- Glenn Close as Carrie Johnson, Troy's devastated mother. She tries to mask her grief with a cheerful persona, and continually guilts her neighbors by telling them bluntly that she does not blame them for Troy's death.

- William Fichtner as Bill Stiffle, Dean's psychiatrist father who uses Dean as the subject of his books. Though he spends his life always looking for potential new material, his book sales turn out to be disappointing.

- Ralph Fiennes as Michael Ebbs, the mayor of Hillside and Terri Bratley's fiancé. After suffering a head injury and spilling paint in the shape of a dolphin, he becomes infatuated with dolphins and paints them all over his house; at the end of the film, he resigns from politics and becomes an artist.

- John Heard as Lou Bratley, a police officer and Charlie Bratley's father. He cannot let go of his previous marriage with Terri, and finds satisfaction in giving her copious parking tickets.

- Allison Janney as Allie Stiffle, Dean's overworked mother. She initially struggles to sell her VeggiForce vitamins, but by the end of the film, she has found success and VeggiForce has become something of a cult.

- Josh Janowicz as Troy Johnson, Dean's best friend and the supplier of prescription drugs to the student body at his high school. After his suicide, he appears frequently in Dean's hallucinations.

- Carrie-Anne Moss as Jerri Falls, Crystal's laidback mother. She is obsessed with Terri Bratley's interior design work, but cannot catch her attention until she tells Terri that her son was at Jerri's house.

- Rita Wilson as Terri Bratley, a successful interior designer and Charlie's mother. She grows increasingly frustrated and demanding as her wedding to Michael approaches, and by the end of the film her design efforts have become less fruitful.

Themes

[edit]The title of the film refers to a video game character, "The Chumscrubber", who helps his friends to survive in a superficial world by keeping things authentic, and is portrayed as a post-apocalyptic hero, carrying his severed head in his hand as he fights the forces of evil. The Chumscrubber's world was intended to be a reflection of the Hillside community, shown by the repetition of characters' lines in the video game; a voice in the game yells "Kill him! Stab him! Get him again!", the exact line said by Billy to Lee at the end of the film, urging him to stab Charlie Bratley.[7] Producer Bonnie Curtis described the character as "this sub-human monster the kids feel they are becoming".[8] Posin commented that "the Chumscrubber is everything that that community has suppressed or denied or tried to ignore, and [...] the idea that the collective denial of the community as a whole finally gives birth to a character that will not be ignored".[9]

Posin stated that one theme of the film is that "the adults in this world tend to be immature or childish and the kids tend to be very mature and adult and sophisticated for their age".[7] He shot the teenage characters slightly below eye level to create the impression of looking up at an adult, and shot the adults slightly above eye level as if the viewer were looking down at a child.[7] He said that hypocrisy was "at the top of the list" of the themes he wanted to explore in the story.[10] While all of the adults in the film are attempting to live perfect lives, they cannot see that their children are driven to suicide, antidepressant addiction and kidnapping – for instance, Terri is so obsessed with her upcoming wedding that she does not realize her son is missing.[10]

The film features dolphins as a recurring motif. Michael forms an obsession with dolphins and paints them all over his house, the street plan of Hillside is shown to form the shape of a dolphin at the end of the film. Nathan Baran of Hybrid Magazine was frustrated by the lack of explanation of the motif, saying: "Never are dolphins discussed by anyone else to have any meaning whatsoever. [...] What is the significance of the dolphin as an image? [...] it is a completely arbitrary image awkwardly stuffed with forced meaning".[11] Posin saw Hillside's formation of a dolphin shape as "beauty and order to the chaos", illustrating Michael's belief in deep beauty where everybody else finds chaos.[9]

Production

[edit]While working at a Hollywood talent agency Arie Posin had been writing scripts for 10 years, "trying to break in[to]" the film industry, when he decided that he would rather be a director than a screenwriter.[7] Posin asked writer Zac Stanford to write the screenplay for The Chumscrubber based on his idea.[7] Because they collaborated on the story, Posin later described the film as "rooted somewhere between" his own memories of growing up in suburban Irvine, CA and Stanford's upbringing in a small town in the Pacific Northwest.[12] Posin and Stanford had originally planned to shoot the film with their own money. Posin's girlfriend suggested that he send the script to five producers; one, Lawrence Bender, responded and passed the script on to his partner Bonnie Curtis.[7] Posin and the producers brought the project to approximately 60 uninterested production companies before sufficient funds for the US$10 million budget[4] were raised and production began.[7]

Posin considered numerous other actors for the lead role of Dean before he decided to cast Jamie Bell. Auditions for the role spanned over a year, and Posin said that he met "probably every young actor in Hollywood between a certain age".[13] For the role of Crystal, Posin sought a beautiful but fragile actress. He chose Camilla Belle after she auditioned, and according to him, "She just was the character".[9] Posin wanted an actor similar to Ralph Fiennes to play Michael, but was surprised when Fiennes himself agreed to be in the film.[7] Justin Chatwin, a Billy Wilder fan, was drawn to the script after hearing that Posin had trained with Wilder.[14] Ben Kingsley and Robin Williams were set to star in the film at different points in pre-production.[4]

Principal photography of The Chumscrubber began in April 2004 and lasted for 30 days.[10][15] Filming locations included Los Angeles and Santa Clarita in California,[16] as well as two soundstages.[10]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Chumscrubber premiered on January 25, 2005 at the Sundance Film Festival.[17] It went on to be shown at the 27th Moscow International Film Festival in June 2005,[18] where it won the Audience Award.[19] The film was released theatrically in the United States on August 5, 2005, playing in 28 theaters. It earned US$28,548 on its opening weekend, ranking 59th at the box office. It closed after two weeks in release with a total domestic gross of $52,597.[5] The film's highest-grossing international releases were in Australia with $96,696, Germany with $81,323, and Greece with $71,100.[20] It earned only £36 from its single-weekend release in the United Kingdom, meaning that only six people paid for a ticket to see the film.[21] With a total international gross of $298,804, the film's total worldwide gross was $351,401[5] and was a box office bomb.

Critical response

[edit]As of June 2020[update], on Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 37% based reviews from 60 critics, with an average rating of 4.95 out of 10. The site's critical consensus states "This derivative poke at suburbia falls short of delivering a scathing indictment of upper middle-class disconnect."[22] On Metacritic it has a score of 41 out of 100 on based on reviews from 12 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[23]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone gave the film 1 star out of 5, describing it as "an appallingly clumsy and stupid take on drugs, kidnapping and suicide in suburbia".[24] A. O. Scott expressed similar sentiments in The New York Times, calling the film "dreadful" and criticizing its unoriginality.[25] Variety's Scott Foundas also wrote that the film "doesn't have an original bone in its body or a compelling thought in its head" and called it "insufferable", "self-conscious" and "smug".[17] Olly Richards of Empire gave the film 2 stars out of 5 and described it as "a tragic waste of acting talent, with nothing new to say."[26] The A.V. Club's Keith Phipps praised Posin's technical direction and the cast's acting skills, but found that the film still fell "flat on its face".[27]

The film was more warmly received by David Sterritt of The Christian Science Monitor, who described it as "dreamily surreal, acutely intelligent, and strikingly tough-minded" and called it a "stunning directorial debut".[28]

Home media

[edit]The film was released on DVD in Region 1 on January 10, 2006. The special features included on the disc are an audio commentary from Arie Posin, a 12-minute "making-of" featurette, and 10 deleted and extended scenes.[29]

Soundtrack

[edit]

| The Chumscrubber: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various Artists | |

| Released | October 18, 2005 |

| Length | 55:16 |

| Label | Lakeshore Records |

| Producer | Chris Douridas |

The film's original score was composed by James Horner. Though Horner's previous work comprised mostly high-budget studio films – including Titanic (1997), Braveheart (1995), The Mask of Zorro (1998), and Apollo 13 (1995) – producer Bonnie Curtis approached him to score The Chumscrubber because "You never know until you ask." Horner agreed after seeing an early cut of the film. He and Posin spent five days on a soundstage, experimenting with different musical arrangements. Posin described the final product as "dramatic with a wink and a smile to it".[8]

- "Our House" – Phantom Planet

- "Bridge to Nowhere" – The Like

- "Run" – Snow Patrol

- "Pure Morning" – Placebo

- "Oblivion" – Annetenna

- "Spreading Happiness All Around" – James Horner

- "Kidnapping the Wrong Charlie" – James Horner

- "Dolphins" – James Horner

- "Pot Casserole" – James Horner

- "Digging Montage" – James Horner

- "Parental Rift/The Chumscrubber" – James Horner

- "Not Fun Anymore..." – James Horner

- "A Confluence of Families" – James Horner

- "The End" – James Horner

References

[edit]- ^ "The Chumscrubber (2005)". The Numbers. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ The Chumscrubber at IMDb

- ^ "The Chumscrubber". BFI Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c Fetters, Sara M. (August 5, 2005). "The Chumscrubber Interview (Part 2)". MovieFreak.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c "The Chumscrubber: Summary". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ Deming, Mark. "The Chumscrubber". Allmovie. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on 2012-06-30. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "CHUMSCRUBBER duo Arie Posin and Bonnie Curtis chat up Quint". Ain't It Cool News. August 18, 2005. Archived from the original on October 12, 2006. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ a b "The Chumscrubber". WritingStudio.co.za. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c Baran, Nathan (August 2005). "The Chumscrubber—Nathan Baran interviews director Arie Posin". Hybrid Magazine. Archived from the original on July 4, 2010. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "The art of writing and making films: The Chumscrubber". WritingStudio.co.za. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ Baran, Nathan (August 2005). "The Chumscrubber". Hybrid Magazine. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Riggins, Marleigh (November 15, 2005). "LAist Interview: Arie Posin". LAist. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ Gilchrist, Todd (January 12, 2006). "Chafed About The Chumscrubber". FilmStew.com. Retrieved December 30, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Pucci, Lou Taylor (August 2005). "Justin Chatwin: he may not have been a whiz in chemistry class, but he sure knows how to get reactions". Interview.

- ^ Laporte, Nicole (April 18, 2004). "Thesps bound for El Camino". Variety. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ "The Chumscrubber (2005)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2008. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Foundas, Scott (March 2, 2005). "The Chumscrubber". Variety. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ "27th Moscow International Film Festival (2005)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ^ Henderson, Craig (2007). "Knockout Belle" (PDF). Factory: The Film Industry Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "The Chumscrubber: Foreign Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ Gritten, David (November 25, 2007). "Sadly forgotten films thriving in the afterlife". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "The Chumscrubber (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "The Chumscrubber". Metacritic. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Travers, Peter (August 5, 2005). "The Chumscrubber". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (January 31, 2005). "Nonfiction Has Its Day at Sundance". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Richards, Olly. "The Chumscrubber". Empire. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Phipps, Keith (August 16, 2005). "The Chumscrubber". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Sterritt, David (August 5, 2005). "Movie Guide". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Simon, Brent (February 6, 2006). "The Chumscrubber". IGN. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

External links

[edit]- 2005 films

- 2000s teen comedy-drama films

- American black comedy films

- 2005 black comedy films

- American teen comedy-drama films

- English-language German films

- Films scored by James Horner

- Films about drugs

- Films about dysfunctional families

- Films about missing people

- Films about suicide

- Films directed by Arie Posin

- Films produced by Lawrence Bender

- Films set in California

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Manitoba

- German comedy-drama films

- Go Fish Pictures films

- American independent films

- German independent films

- Films produced by Bonnie Curtis

- 2005 directorial debut films

- 2005 independent films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s German films

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language independent films