What you need to know

Oppressed under martial law and underappreciated in their native land, Taiwan's comic artists still managed to leave their mark on the minds of millions across Asia.

“Did you read manhua when you were a kid?”

My dad shovels freshly-steamed rice into a bowl. This was an awkward family conversation — manhua (

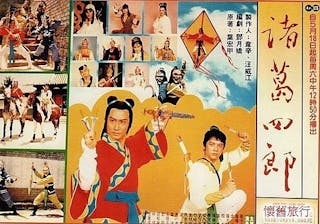

“Of course,” he grudgingly admits.“What kind? "Like Zhu-ge Si-lang? (

Dad smiles as if struck by a fond memory. Zhu-ge Si-lang was the most popular manhua on the island back in the 60’s. Pop singer Lo Da-yu (

Credit:

“What about Liu Hsing-chin (

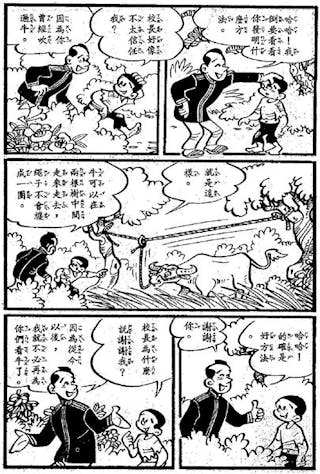

I remembered the stack of Liu’s comics still up in the attic. In his book "Taiwan Manhua Yuelan" (

My personal favorite was his Xiao Bo-shi (

Credit: Hakka Affairs Council

But Liu's life was not all fun and frolics. His is just one of many life stories that highlight the tumultuous struggle for survival faced by Taiwanese artists and their work.

Not so funny: The Comic Code

Liu was forced to leave the field of comics to become a successful inventor of educational toys after the introduction of the notorious Comic Code.

The Comic Code (

“In every image, there should be a clear distinction between foreground and background. There should be an even combination of density, movement and attitude. The structure of the image should attain an effect that is stable, harmonious and lively. Lines are either crossed, paralleled or curved; surfaces are separated into triangles, squares and diamonds. Light contrast and elaborateness of the background correlates to the needs of its subject in order to compliment but not trump the subject. Scenery should be realistically portrayed rather than dismissively filled up with blocks, lines or patterns.”

Local artist Mickeyman sums up the reaction of the comic community to the regulations: “I want to make a manhua that depicts the ludicrousness of those times,” he tells TNLi. “How lasers and super missiles, weapons that were beyond the technology of the age were not allowed to be portrayed. Crazy scientist characters that wanted to rule the world were forbidden, because science is supposed to be good. I know I’m sounding like an old fogey but this is how you kill creativity with policies.”

The Comic Code began to be enforced around 1966 and lasted until the end of martial law in 1987, during which all books and magazines with over 20 percent manhua content had to be submitted to the National Institute for Compilation and Translation (

During this period, cheaply-printed pirated Japanese manga came to dominate the market, as copyright laws for foreign works in Taiwan weren’t revised until 1992, a condition for Taiwan to join the WTO.

This is also the main reason why my parent’s generation – those who were children during the so-called “Golden Decade” of Taiwanese comics from 1965-1974 – grew up on locally-produced Taiwanese strips. My generation, those born after the end of martial law, were brought up on Japanese manga: Doraemon, Sailor Moon, Yu Yu Hakusho, Dragon Ball, etc. Japanese comics will likely continue to dominate the industry; according to a report by the National Central Library some 90 percent of the comics published in Taiwan were imported from Japan in 2015.

Taiwan's 1980s manhua renaissance

Taiwan did not submit to this Japanese dominance without a struggle. Under the advice of Taiwanese comic scholar Hong De-lin ( Hong De-lin), the Cartoonist Association of the Republic of China collaborated with China Times to hold three National Manhua Competitions (

“We were still under martial law back then – there was nothing cute or funny in the newspapers, so it looked as if a small flower had blossomed at the edges,” manhua artist Ao Yo-hsiang (敖幼

Cut to September 2017, and President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡

But the comments touched a nerve. The brief renaissance enjoyed in the 1980s had given way to another period of struggle as Taiwanese artists fought an influx of Japanese titles, and government efforts to stem the tide had proved ineffective. In response to Tsai's olive branch, then head of the Taipei Comic Artist Labor Union Chung Meng-shun (鍾孟

Chung blamed this brain drain on the lower rates paid to comic artists in Taiwan. “A decade ago, one page could fetch NT$2,000, now it’s only NT$800 -1,000 per page,” he said in an interview. Chung gave voice to widespread discontent in Taiwan's manhua community, which felt stung by state-led plagiarism that had seen the government appropriate copyright-free foreign designs for policy posters and mascots rather than reaching out to local artists.

To cap it all, Chung's mentor Chen Uen (1958-2017) passed away last year, bringing into even sharper relief how untenable the situation had been for even the most successful Taiwanese artists – Chen himself had been forced to make his way across the Strait in China.

Remembering Chen Uen

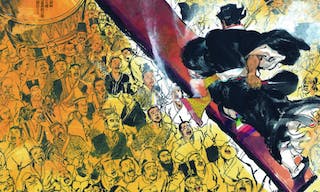

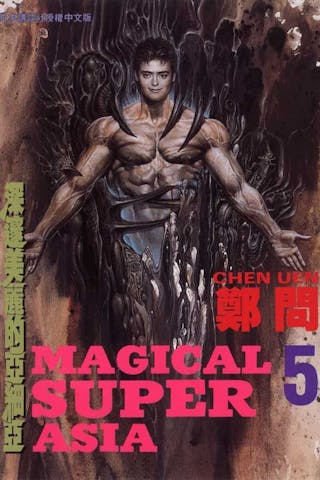

Chen Uen made his manhua debut in the magazine China Times Weekly in 1984 and won special commendation in the National Manhua Competition of 1985. He was known for his experimental ink-wash technique that utilized scraps of cloth, soap and dirty ink brushes to create realistic characters with surreal body features.

Having published in Taiwan, Hong Kong and China, his manga series “Heroes of the East Chou Dynasty” (

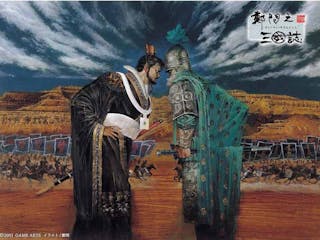

“The writer Soseki Natsume’s grandson (Fusanosuke Natsume) was so dismayed that a foreigner won the award that he wrote a piece about it in the newspaper,” commented Chung. Chen also had a game named after him, "Chenwen no Sangokushi" published by Japanese company Game Arts, which drew on his work and hired him as the illustrator for a game based on the ancient Chinese novel "Romance of the Three Kingdoms" (

Credit: thedawncreative

Yet despite the overseas accolades, Chen Uen was not as well known as he should have been in Taiwan. “He often compared himself to an orchid with no roots,” Chung said, commenting on how Chen had been forced to move abroad during the early days of his career due to Taiwan’s unfavorable conditions for manhua artists.

The "orchid with no roots" is a reference to the patriotic Song Dynasty painter Zheng Sixiao (

Chung rammed home the message in the aftermath of his mentor's death. In an article headlined "“What Taiwan doesn’t care for, the outside is clamoring over: Chen Uen Art Museum Might Be Built Across the Straits”, Chung complained that it was Chinese investors showing interest and financial appetite to continue his mentor’s legacy. Some of them offered to buy the licensing rights to adapt Chen's works into games and video, while others offered royalties so they could hold an exhibition. In Taiwan, there was “not even the sound of a cricket,” the artist wrote.

“Would it be against his will if we moved his works out of Taiwan, does this mean he’s doomed to be an orchid without roots even after his death?” he asked.

Chung’s complaints did the trick. A week later, he told the press that the National Palace Museum had agreed to hold a retrospective in Chen's honor. “I won’t be too fussy, since it’s the National Palace Museum,” he said. The exhibition was originally set to open in March 2018, on the anniversary of Chen's death, but was later rescheduled to June to coincide with summer vacation.

Credit: Manhuagui

Bridging the generation gap

Manhua artists who came to fame during the 80s often find themselves unable to speak to today's Taiwanese readers in the present. These artists were mostly born in the late 50s and early 60s, and their formative years were passed during the KMT’s authoritarian rule.

While many were forced to seek audiences and freedom of expression overseas, they did their best to take a piece of Taiwan with them.

Around 1966, in reaction to the PRC’s Cultural Revolution, when relics of traditional Chinese culture were destroyed as reminders of feudalism, Chiang Kai-shek (蔣

Chinese culture thus became a torch that Taiwanese manhua artists could carry across international borders. In 2016, Taiwanese artist Tsai Chih-Chung (蔡志

‘I thought to myself, what would be a commercial success? What could I draw that the Japanese couldn’t? So I proposed the Hundred Schools of Thought. I handed the first 80-paged sketches on Zhuangzi (

Tsai has since published a series of manga adaptations on Chinese thinkers such as Confucius, Laozi and, Suntzu in Japan. The series was such a hit that it has now been translated into more than 20 different languages.

Chen Uen is also instructive in this regard. Though Dala Publishing chief editor Huang Jian-He (

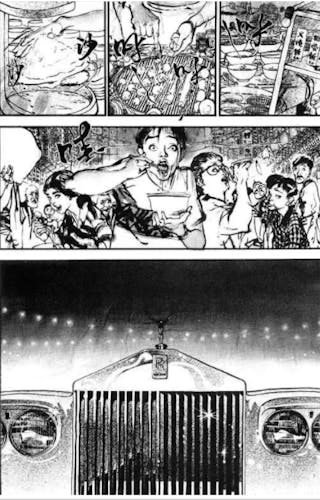

In the 25th anniversary edition of "Super Magical Asia", published by Dala several months after the Chen’s death, the artist's Japanese editor Shin Yasuyuki (

Credit: bahamut

“It was 1989,” wrote the editor, “I arrived in Taipei to meet Mr. Chen. I still remember how I saw the Grand Hotel as Chinese architecture par excellence; coupled with the dense advertisement boards on the street, with uncountable motorcycles, the excitement was overwhelming.”

It is unclear whether or not Shin was aware that the Grand Hotel was one of the staple projects of Chiang’s Chinese Cultural Renaissance, built to replace the Taiwan Grand Shrine that dated back to Taiwan’s Japanese colonial era. Yet if Chiang’s mission was to inspire awe and admiration for KMT rule through the aesthetics of Chinese culture, he was successful. Shin, musing on the scenery, thought to himself: “If the world was not dominated by Europe or America, but Asia, then perhaps the entire world would look like this?”

It would also not be too much of a stretch to say that aside from its association with Chinese culture, Shin didn’t think much of Taiwan. “Like a lotus growing from the muck,” was how the Japanese editor first described Chen in Kodansha press’ newsletter back in the 80s. Shin apologized for using the word “muck”, but went on to explain that Taiwan, especially during the 80s, was a headache since there were no laws that prevented a giant wave of pirated Japanese manga from appearing on the island.

The association with Chinese culture benefited the Taiwanese economically and provided them a sense of cultural pride. But times have changed.

By 2008, people in Taiwan that identify as primarily Taiwanese rather than Chinese began to outnumber those that perceived themselves as both Taiwanese and Chinese, according to the Election Study Center at National Chengchi University (NCCU).

Yu Chen-hua (俞振

Taiwanese identity — a new path for the comics industry?

The embrace of traditional Chinese culture by the PRC did not happen overnight, but began in the 90s during the “national studies” craze that hoped to reclaim traditional Chinese culture that was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. This is also why many manhua artists who came to fame during the 80s are currently even more popular in the PRC than in Taiwan. For example, Tsai Chih-Chung (蔡志

Chinese IT company Tencent has also just hired him as adviser for their collaborative project with Dunhuang Academy, which aims to promote the city of Dunhuang as a significant stop on the Silk Road and a notable religious site for Chinese Buddhism through popular mediums such as games and manhua.

If the PRC has taken back the claim to be the authentic China, what else is there for Taiwan? The backlash faced by attempts to change the high school curriculum to focus less on classical Chinese and more on Taiwanese literature perhaps bears witness, in some form, to the belief that Taiwan will become a cultural desert without its attachment to ancient Chinese culture.

Chung Meng-shun has emphasized the need to elevate manhua for the sake of national security. “If you don’t protect your own culture you will be invaded by others!” he told the talk show Yao’s Trending Taipei.

On his Facebook, Chung added: “No matter how good a nation’s manufacturing business is, even when every chip in the world is made by us, it doesn’t make [Taiwan] a country, it just makes us a factory. When a country has an IP so strong that it influences others ... the world will have to recognize your existence and consider your right to speak. That is the only way for Taiwan. This is also what I mean by manhua as a form of national defense.”

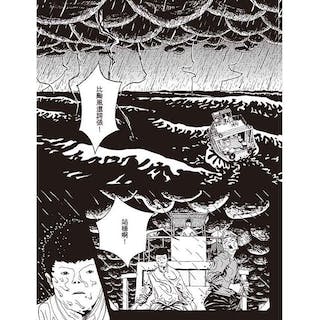

However, perhaps we shouldn’t fret too much. A fragmented sense of self is a more interesting to play with. Take, for instance, the manhua artist Chen Jian (

Credit: theinitium

A-lang finds a young boy, Hei-ze Yong, drifting in the middle of the Kuroshio Current. Though the boy suffers from amnesia, a name tag with the Chinese characters, Hei-ze (

Later, as a grown man, Hei-ze travels to Japan to promote his manga career, resulting in further complications. The work does not suggest a romanticized, unified image of ancient China, but presents an uneasy, untidy ambiguity in which identity is not prescribed, but relies on free, conscious choice.

That's not such a bad message for Taiwan's manhua to share with the world.

A podcast covering Julia's exploration of Taiwan's comics can be found at Department of Nerdly Affairs here.

Editor: TNL Staff