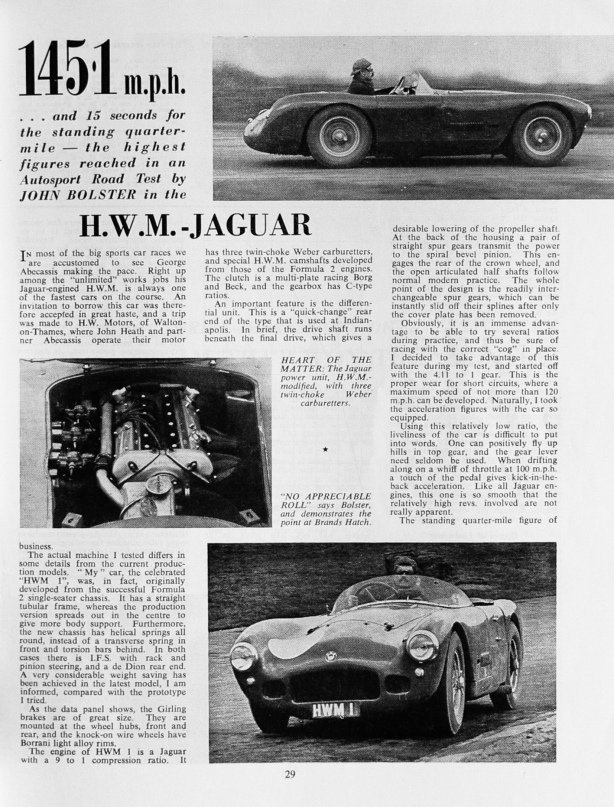

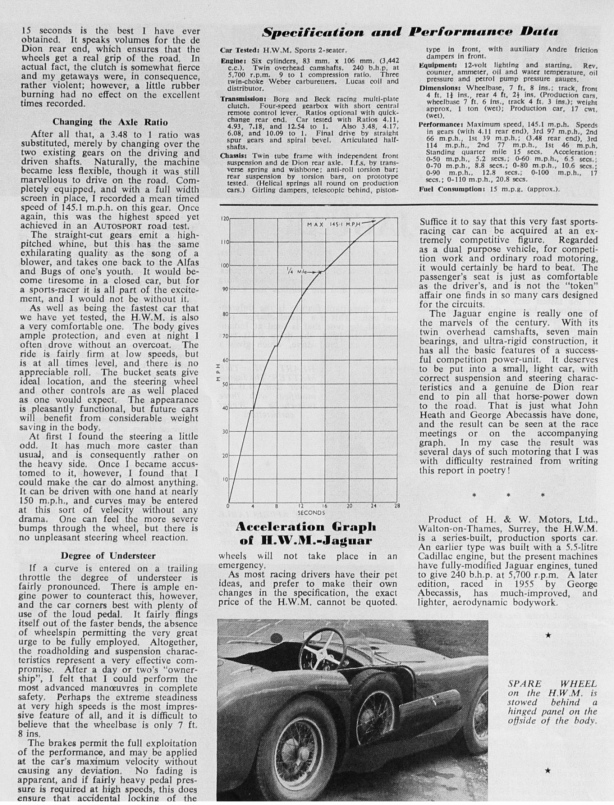

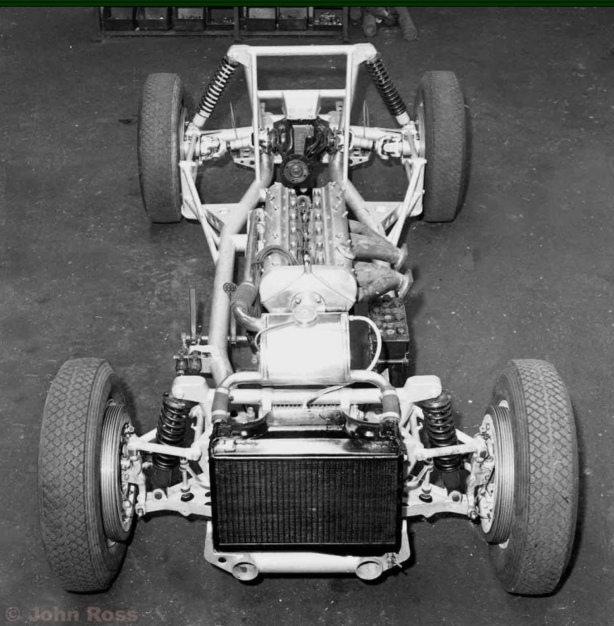

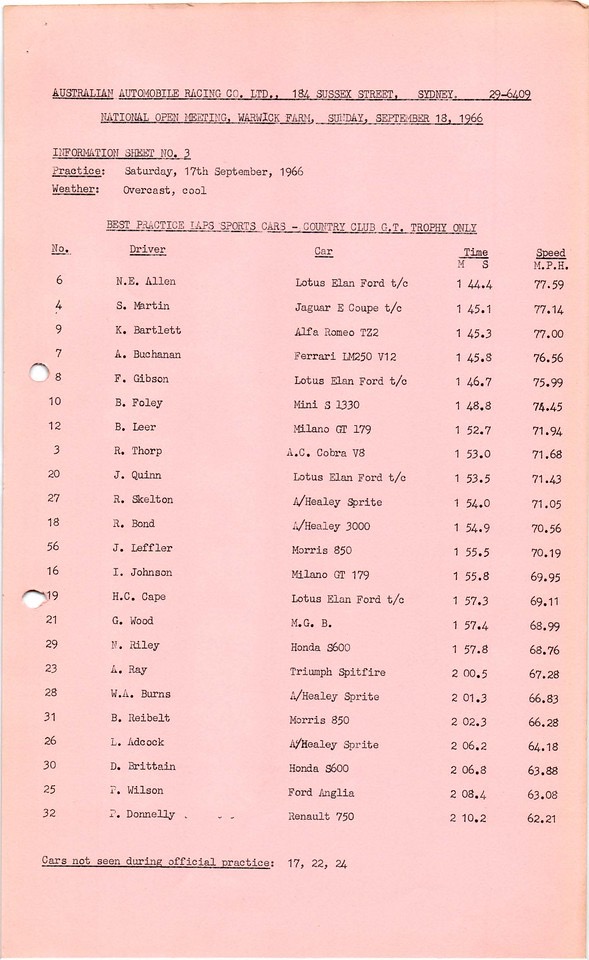

Allan Moffat finesses his Shelby Mustang around the Daytona banking during the 1968 running of the endurance classic on 4 February…

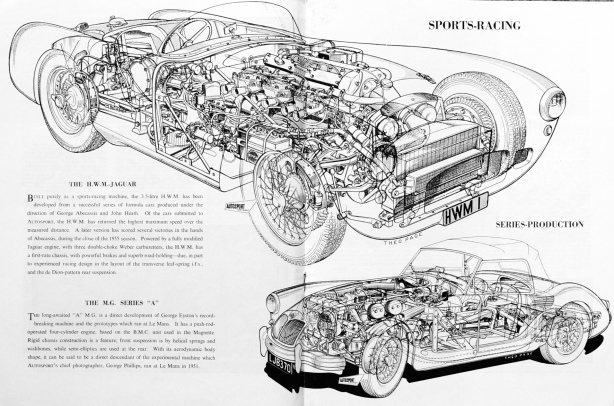

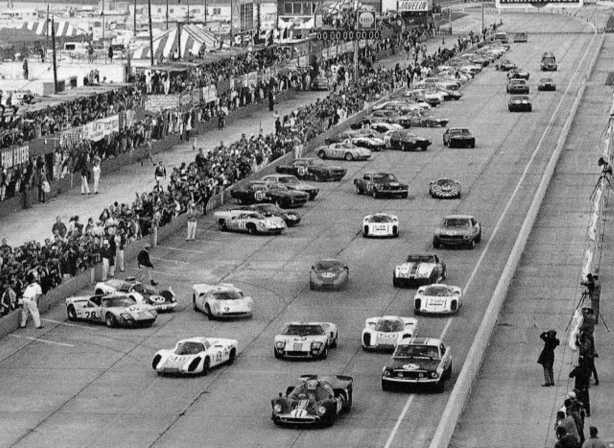

The first two World Sportscar Championship rounds in 1968- at Daytona and Sebring were also the first rounds of the Sports Car Club of America’s Trans-Am Championship which had very quickly become an important ‘Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday’ contest for the major manufacturers and importers of cars into the US since it’s inception in 1966- the ‘Pony Cars’ so many of us know and love are a by-product of the Trans-Am, more to the point, they provided the homologation foundation upon which the race winners were built.

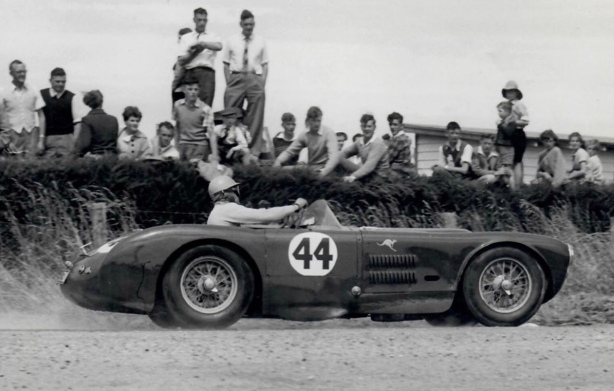

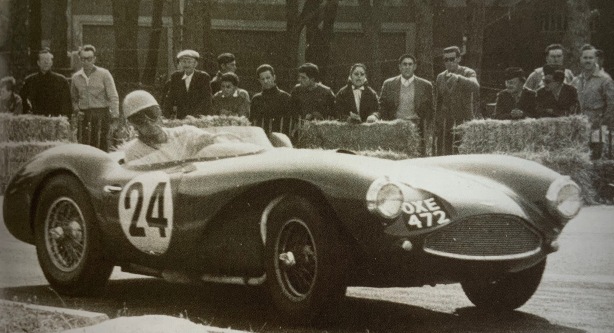

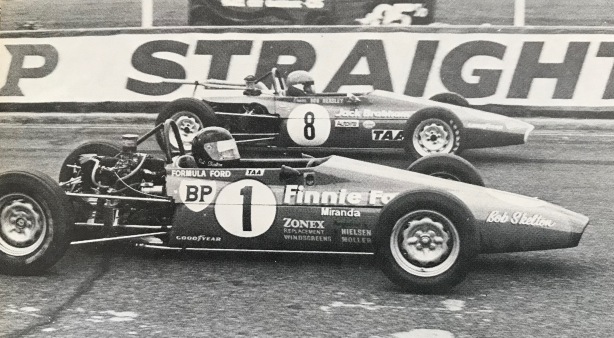

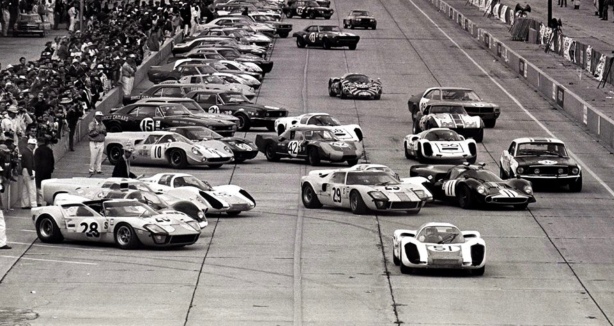

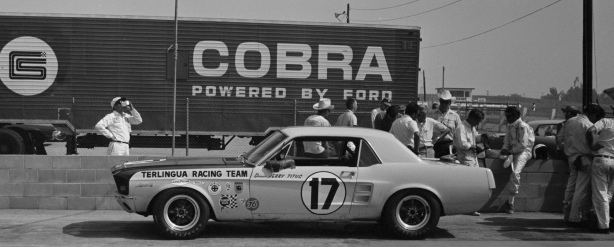

Shelby Racing Company entered two new ‘tunnel port’ 305cid V8 Mustangs at Daytona crewed by Jerry Titus and ex-F1 driver Ronnie Bucknum and another raced by Allan Moffat and Austrian/Australian/American Horst Kwech- they qualified Q22 and Q23 respectively.

Siffert/Hermann Porsche 907 second placed car (the pair also shared the winning #54 car!) in front of Moffat/Kwech/Follmer Daytona 1968 (D Friedman)

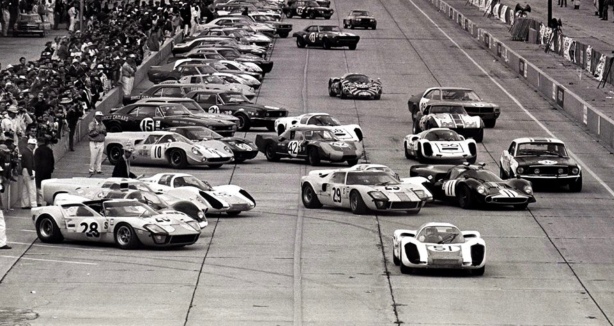

Whilst the Porsche 907, Alfa Romeo T33, Ford GT40 and Lola T70 slugged it out at the front of the field- that battle was settled in favour of the Vic Elford/Jochen Neerpasch/Rolf Stommelen Porsche 907 with 673 laps from the Jo Siffert/Hans Hermann 907 in second, Ford were fourth outright courtesy of the Titus/Bucknum combination who covered 629 laps- the Moffat car failed to finish when a spring tower failed. Ford were fortunate in that Roger Penske’s Chev Camaros had been ahead of the Mustangs, but they too did not finish.

Daytona 1968 pre-race prep for the two ’67 rebuilt Shelbys, Titus car in front of Moffat’s (D Friedman)

Moffat from the Kleinpeter/Mummery/ Hollander Shelby 350 DNF- the blaze of lights getting Moff’s attention is the Wonder/Cuomo Ford GT40 DNF (unattributed)

Thaddl be during the long night- car DNF after 176 laps (D Friedman)

Whilst Allan Moffat is a household name in Australia, he may not be quite so well known to some international readers so a potted history follows, noting the focus of this article is two years or so of his long, successful career- 1967 through to the middle of 1969.

Despite the articles narrowness in time it’s 13,594 words in length which is insane really, my longest ever, and about Touring Cars FFS! but I got more and more interested and chased increasingly many tangents as I explored. Grab three ‘Frothies’, here goes…

Allan George Moffat was born in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada on November 10, 1939. His father’s career progression took the family to South Africa in the early 1950s. Moffat’s high school education spanned 1953 to 1958- he attended General Smuts High School in Vereeniging, near Johannesburg.

Keen on cars from the start, he bought a 1935 Ford V8 aged sixteen then stripped and rebuilt it over two years before he was able to drive on the roads, the first circuit he visited was Grand Central track- what became Kyalami, a ‘citadel’ of racing. Allan’s father moved the family to Melbourne, Australia in 1961 where he became a cadet with Volkswagen and attended night-school at Taylor’s Business College with the aim of being admitted into university.

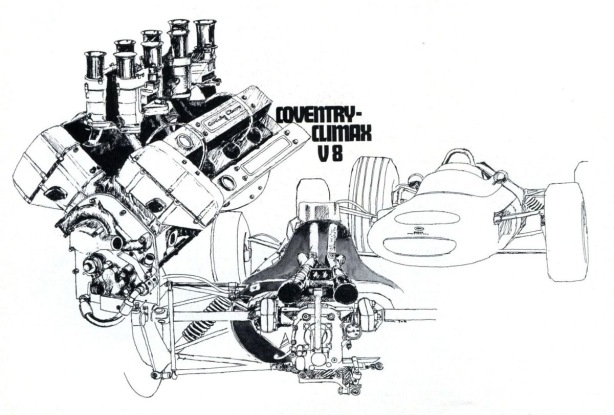

Sandown’s first international meeting was held on 12 March1962, he blagged a his way into a gopher role with the Rob Walker camp helping look after Stirling Moss’s pit- the great Brit was third in a Lotus 21 Climax 2.7 FPF in the race won by Jack Brabham’s Cooper T55 Climax.

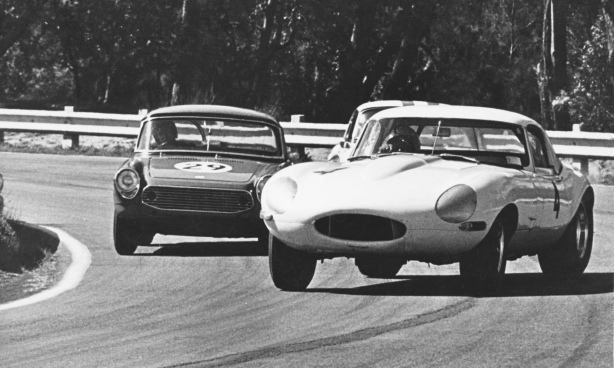

Early days on the Victorian circuits- Moffat, Calder, Triumph TR3A 1963

Moffat and Jim McKeown go at it during the 1966 South Australian Touring Car Championship at Mallala- Jim was disqualified for receiving outside assistance after a spin whilst Moffat blew a tyre on the last lap. Clem Smith won in his Valiant RV1 (unattributed)

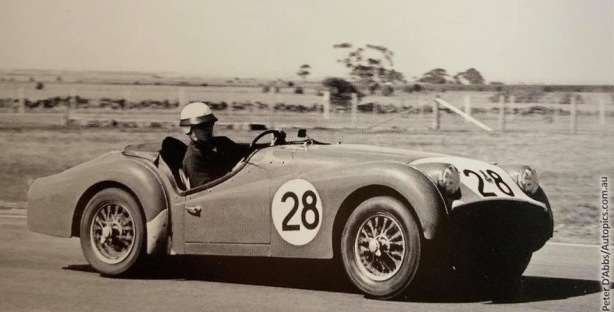

Shortly thereafter the budding racer bought a Triumph TR3A on hire purchase and commenced his competition career at Calder and the country circuits of the day as time and money allowed. He raced a hot VW while studying at Monash University and working with Volkswagen. After failing at Monash he followed his family back to Canada where he made a living selling Canadian cookware door-to door.

If it was ever in doubt, Indianapolis 1964 was the event which decided the young, focused and very determined Moffat that his future was in racing. He travelled from Toronto to Watkins Glen to see Team Lotus race their Lotus Cortinas to try and get a job with the team. He sought out Australian Ray Parsons all weekend about helping the team but failed so, ever persistent, followed them 2900 kilometres away to Des Moines- the next event where he met Parsons who took him on without pay- by the next meeting at Washington he was accepted into the team albeit on an unpaid basis.

At the seasons end the Cortinas were advertised for sale at $4500 each including spares- Allan asked his father to lend him the $3000 shortfall in excess of his savings to buy one, he reluctantly agreed. The deal was done and the car quickly shipped to Australia where he contested the 1964 Sandown Six-Hour race, a high profile international event with all of the local touring car stars of the day and internationals Roberto Businello, Paddy Hopkirk, John Fitzpatrick, Rodger Ward, Timo Makinen, Rauno Aaltonen, Jackie Stewart and Jim Palmer. After twenty laps Moffat had lapped Bob Jane and was leading the race but boofed the fence at Peters Corner, eventually finishing fourth- it was a magnificent debut all the same. The race was won by Businello and Ralph Sach in Alec Mildren’s Alfa Romeo Giulia Ti Super.

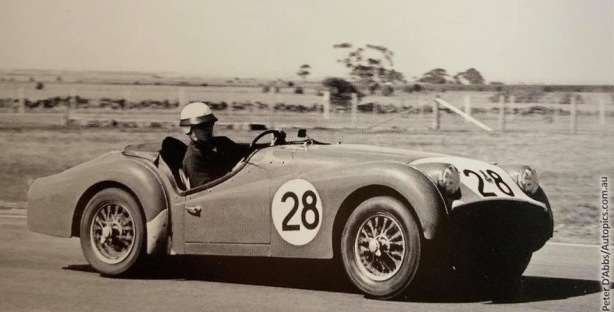

Allan Moffat two-wheeling Shell Corner in best Lotus Cortina style during the November 1964 Sandown 6 Hour- he and Jon Leighton were fourth in the race won by Roberto Businello and Ralph Sach in Alec Mildren’s Alfa Romeo Giulia Super TI (unattributed)

Moff checks the tyres of his FJ Holden Panel Van with Lotus Cortina on the back circa 1965. This servo- the pumps were soon to go, became AM’s workshop from the mid-sixties until 2015, 711 Malvern Road, Toorak is well known to eastern suburban racing nutbags. The locale is much the same now- those houses abut Beatty Avenue are still there. What is different, sadly is that Allan sold the site circa 2015, it is now a several story block of apartments named ‘Mandeville Lane’. Moffat lived in Toorak forever and was a regular in ‘Romeos’ and ‘Topo Gigio’ restaurants in Toorak Road, both are still there, where he was often wining and dining contacts, sponsors etc (AMC)

Moffat, Lotus Cortina, Green Valley 4 Hour Trans-Am April 1967, 18th with Gurney’s Cougar the winner (J Melton)

Moffat raced his car to a win in the Victorian Short Circuit Championship at Hume Weir a month after Sandown and was part of a posse of well over 20 drivers who ‘put the Ford Falcon on the map’ in Australia and dispelled concerns about the marques quality and durability by staging a 70,000 Mile Reliability Trial over nine days in late April 1965.

Ford America still had two unsold Lotus Cortinas so the competition manager, Peter Quenet asked Moffat to come back to prepare and race one of the cars throughout 1965, he returned to the US in time for the Indy 500 and was famously Jim Clark’s ‘water boy’ during the Scot’s historic Lotus 38 Ford victory. He raced the Cortinas in the Detroit area doing consistently well at Waterford Hills, his ‘home track’ but later in the year he raced at Mosport- running a distant third to Sir John Whitmore in a Team Lotus car.

He returned to Melbourne in November 1965 for the six-hour race and was holding second place with his BRM tweaked twin-cam engine when the rear axle failed two laps from the finish- Kiwi open-wheeler ace Jim Palmer co-drove that year.

In early March 1966 Peter Quenet rang again and offered Moffat a drive in Cortinas fitted with a ducks-guts BRM-prepared twin-cams, quick as a flash he was back across the Pacific again. The main competition were the Alan Mann Racing Cortinas whose driving roster included such luminaries as Frank Gardner, Sir John Whitmore and young thrusters Jacky Ickx and Hubert Hahne, in addition the grid that year included about fifteen alloy-bodied Alfa GTAs.

The Alan Mann Racing team manager was Howard Marsden, later to take over management responsibilities of Team Matich in Sydney and shortly thereafter Ford Australia’s racing team which was based in an unprepossessing ‘skunkworks’ in Mahoneys Road, Broadmeadows. In a splendid performance Moffat won the third ever Trans-Am race at Bryar, New Hampshire using U.S. Goodyear tyres, specially developed for his car and in the process his 1.6 litre Cortina defeated heavy metal including Frank Gardner, and John Whitmore Lotus Cortinas Horst Kwech Alfa GTA and ‘heavy metal including the Bruce Jennings Plymouth Barracuda, Yeager/Johnston and Lake/Barber Mustangs, Bob Tullius’ Dodge Dart and others.

Ray Parsons, both a mechanic and a racer, joined Moffat later in the year to build and run another Cortina with Harry Firth and Jon Leighton brought over from Australia as co-drivers for the longer races. At that time Harry Firth was ‘the competition arm’ of FoMoCo Australia preparing both rally and series production racing cars out of his small, famous workshop in Queens Avenue, Auburn. Moffat and Firth- and Parsons and Leighton contested both the Green Valley 6 Hour and the Riverside 4 Hour season ender in mid-September 1966 for ninth/seventh and seventh/thirteenth (both Ray Parsons and Moffat did Riverside solo, the latter when Harry Firth was laid low with flu) outright respectively.

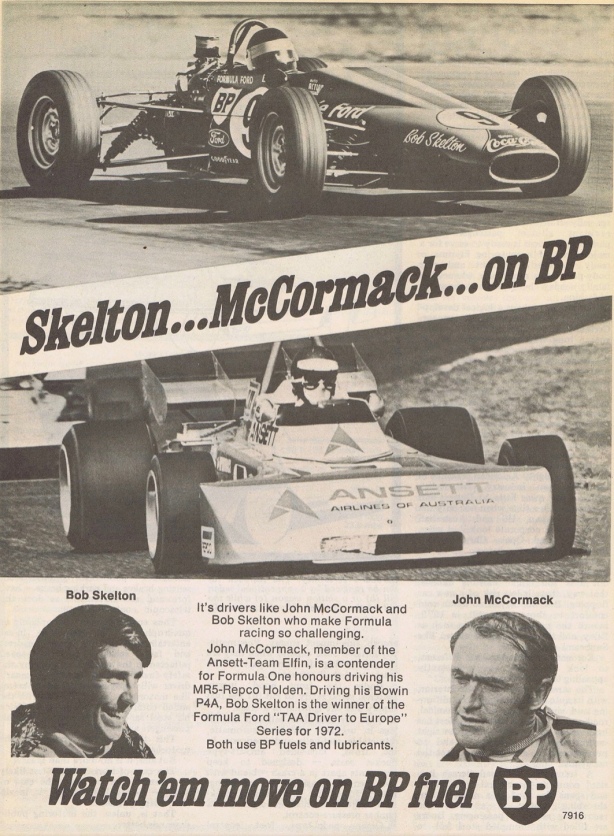

A small historic sidebar is that Ray Parsons was a Tasman Series regular looking after Jim Clark’s Lotuses in the Australasian summers, after he returned to Australia- having tended to Piers Courage’ McLaren M4A Ford FVA in throughout the Etonian’s very successful 1968 Tasman Tour- he joined another ex-Lotus colleague, Engineer John Joyce in Sydney to build the very first Bowin- Glynn Scott’s P3 which just happened to be powered by Pier’s spare FVA. What became of Ray Parsons folks?

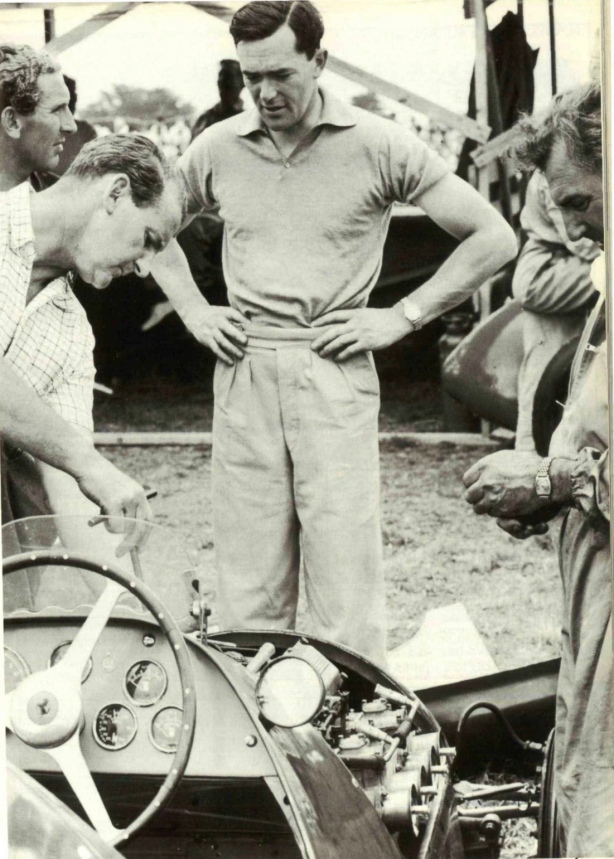

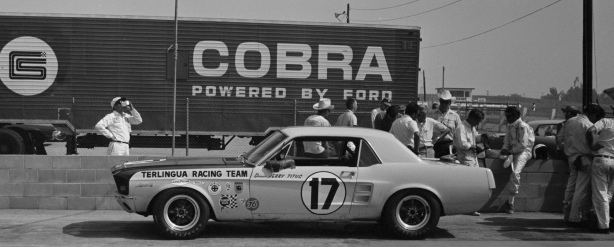

Becoming more and more entreprenueurial, Moffat asked Quenet for a budget to take over and race the two Alan Mann cars for the opening race of the 1967 season at Daytona- the Daytona 300. In a deal that involved Moffat agreeing not to race in Australia in 1967- and with assistance from Shell, the very powerful 180bhp twin-cam engine from Jim McKeown’s Shell-Neptune Lotus Cortina was shipped to America and installed in one of the Mann cars- McKeown was Moffat’s co-driver.

The Canadian got the class pole and led the first half hour before the flywheel parted company with the crank- with that ended any chance of a Ford works deal for 1967 but an agreement was reached whereby Moffat was given the cars, spares, equipment and transporter- and received $300 for each car which started a Trans-Am race.

In order to make the deal financially viable he took on pay drivers who were somewhat rough on the cars. It got to the stage where the other cars were cannibalised to keep his own machine racing- Moff’s results were appalling- Daytona 300 DNF, Sebring 4 Hour DNF, Green Valley 4 Hour eighteenth, Lime Rock DNF, Mid Ohio DISQ, Marlboro U2 litre with Adams DNF and then, bingo, a strong second sharing a Mustang with Milt Minter behind the Donohue/Fisher Roger Penske Chev Camaro Z28 and ahead of other notables in a smallish field in the Marlboro Double 300 at Marlboro Park Speedway in Washington DC.

The one off drive came about when Moffat was asked to take over the drive of a Mustang owned by George Kirksey, a Texan former sports writer and businessman at Mid Ohio- it was a great opportunity which Moffat capitalised upon- the Moffat/Minter pair were third outright at the end of the 500km race albeit they were later disqualified for refuelling whilst the engine was running- an error not Moffat’s. (I can make no sense of this in the ‘Racing Sports Cars’ results of the 11/6/67 Mid Ohio Trans-Am)

Kirksey then invited Moffat to do a non-championship Manufacturers Round at Watkins Glen where the major opposition was the Penske Camaro- Allan put the car on pole, recorded the fastest race lap and were elevated to first place after the winning car was disqualified for running a ‘fat’ engine.

Moffat in front of Dan Gurney’s Mercury Cougars- he would drive one later in the season, here during the March 1967 Sebring 4 Hour, both guys DNF in the race won by Jerry Titus’ Mustang (unattributed)

Moffat, works Bud Moore Mercury Cougar- note Allan Moffat Racing Ltd on the guard, maybe the deal was that AM’s team looked after the car on race weekends? Circuit unknown, help needed(unattributed)

Mercury Cougar test session at Riverside 8-14 January 1967- Bud Moore, Dan Gurney and Al Turner with Fran Hernandez with his back to us. Al Turner came to Australia a year or so later and ‘captained’ Ford Total Performance’ in Australia, bless him (F Hernandez)

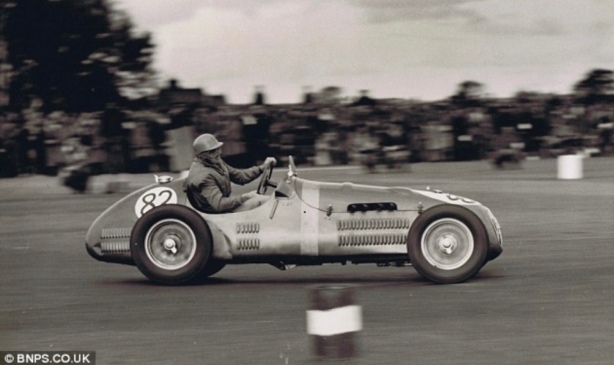

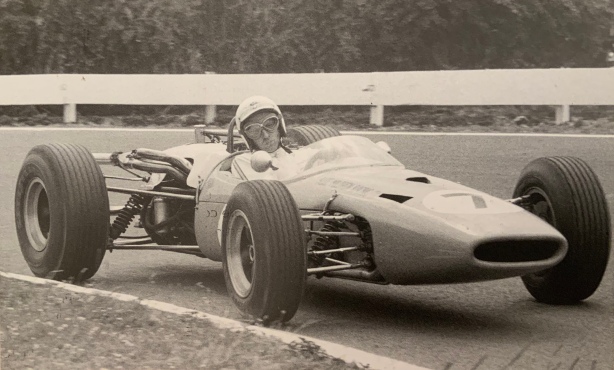

AM in his Brabham BT15 Ford twin-cam, Road America, Wisconsin 1967 (B Nelson)

For the final four Trans-Am races he was given one of the Bud Moore Mercury Cougars and was up there racing with the big boys, a drive Allan credits to Peter Quenet…

His results weren’t flash mind you- his first race was at Modesto on 10 September for a DNF after 9 laps, then a Riverside prang after 41 laps, then in Las Vegasm as a support during the Can-Am round, DNF after 76 laps and then finally in the last race of the year at Kent where he was fifth.

Moffat said of his results ‘In my view it wasn’t my finest hour, but others differed. The DNF’s, two of them not my fault, and an out of points finish in the final race were the sum of my contribution. On paper it didn’t look good, but in that last race i’d actually achieved the team’s objective. I’d been sent out to block, to deliberately spoil the field. And it seemed i’d been successful’ Ford Mustang won the title by two points from Mercury with Chevrolet outclassed.

The young Canadian was very much a ‘coming man’, but he was ‘skint’ so set about selling the Cortinas ‘as well as a Brabham BT15 open wheeler in which i’d had one run and one win at Waterford Hills using a Cortina engine…’

Around about then, in December 1967, Moffat met Kar-Kraft’s Roy Lunn who offered him a job as a development driver. It was during that year (1968) that Moffat either reinforced or established his close links with the various Ford people who would help his career when he returned to Australia- this is about where we came in at Daytona 1968…Shelby, Kar-Kraft and Moffat- a bit player but becoming more significant.

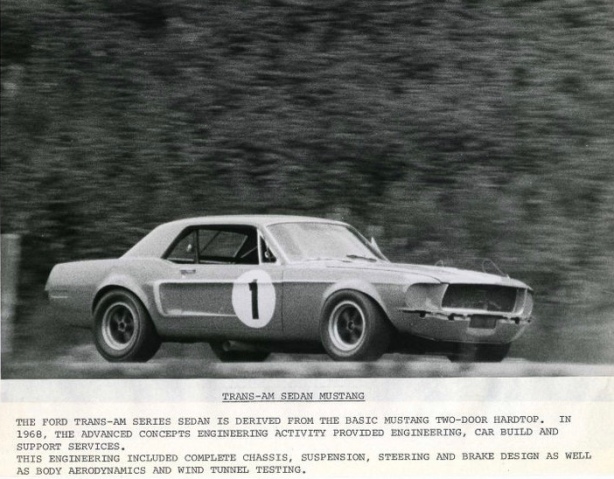

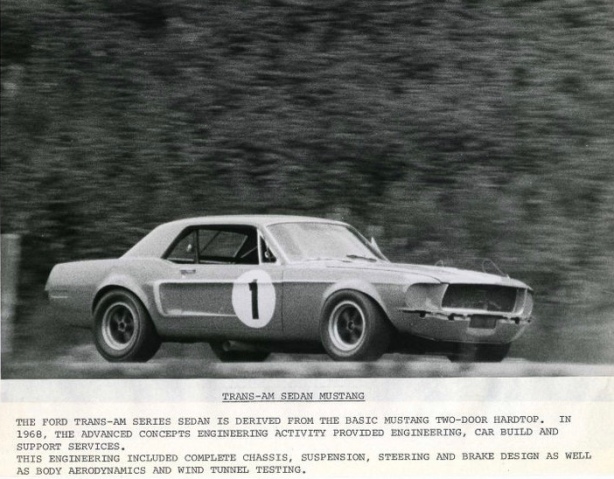

Ford well and truly put a Trans-Am toe in the water by engaging Shelby American to build two Mustang Coupes for the 1967 championship after being successful the year before- Fastbacks could not be used as the SCCA classified them as sportscars at the time- and were therefore ineligible. Kar-Kraft provided valuable engineering assistance to Shelby- in particular making changes to the upper ball-joint mount to provide greater tyre/guard clearance and developing a stronger front axle (spindle). The two Coupes they developed won the ’67 Trans-Am.

Separate to Fran Hernandez’ Mustang program, he also oversaw the the running of (Lincoln Mercury division of Ford) two Bud Moore Mercury Cougars in 1967, one of which was raced by Moffat later in the season as we have just covered. In fact the Cougars almost upset Fords’s championship, falling short by only two points but finishing ahead of the Camaros. According to Lee Dykstra, Bud Moore based the Cougars racers on Shelby Mustang specifications- but they (the Cougars) did not use Kar-Kraft parts.

For 1968 Ford decided to move the Trans-Am Mustang engineering program from Shelby Engineering, based in California to Kar-Kraft just down the road in Dearborn- still with Fran Hernandez as leader. For those of us who are not Americans lets have a look at this short-lived (1964 to 1970) but hugely influential and successful 1960’s race organisation.

Smokey Yunick’s car out front of Kar-Kraft’s Haggerty Street Dearborn facility- building still exists, now used by a shipping company (unattributed)

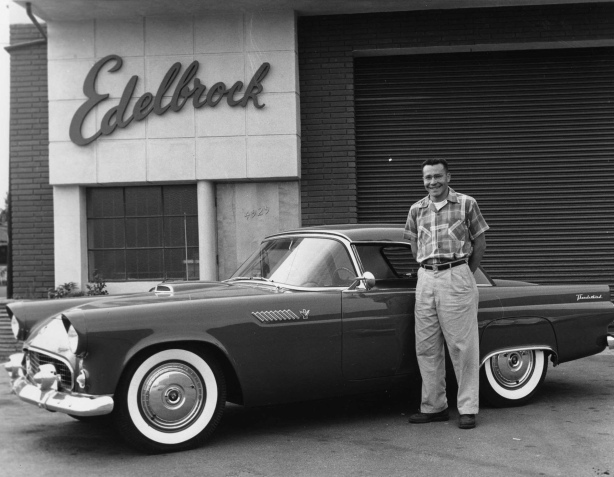

Kar-Kraft was an independently owned racing organisation started by Nick Hartman (although other sources say it was a wholly owned subsidiary of FoMoCo) with only one client- Ford. It was born of a group of young Ford engineers who quickly brought together Lee Iacocca’s mid-engined Mustang 1 concept and build- Roy Lunn was also part of that program and it was that small group who were central to Lunn’s plan for a nimble specialist group to take Ford’s various race programs forward.

Ford Advanced Vehicles in England was Lunn’s responsibility, when he became frustrated with the lack of success/progress of the Eric Broadley designed, FAV/John Wyer built and managed Ford GT40 in 1964 (Colotti gearbox reliability, aerodynamics, outright pace etc) he wanted greater FoMoCo Detroit control and therefore reorganised the GT40 program by tasking FAV to build the chassis/cars in Slough with the race program/development work under the wing of Jacque Passino, Ford’s global motorsport manager- and in turn Kar-Kraft in Dearborn.

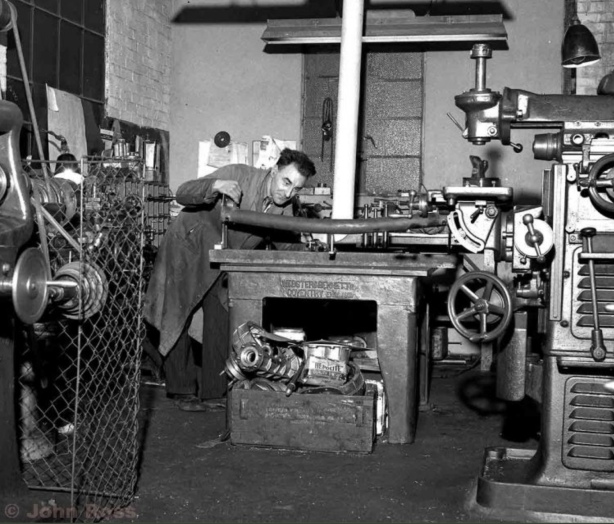

Hartman, Ed Hull and Chuck Mountain knew each other as local SCCA racers, Hartman started K-K upstairs of his father’s machine shop in Dearborn- in the beginning the K-K designers and mechanics were moonlighting from Ford Research with management’s permission.

After a short stay at the Hartman workshop on Telegraph Road, Dearborn, K-K moved to 1066 Haggerty Street where the group was expanded to a team of about four engineers, four designers and ten mechanics and fabricators- flexing in size up and down, who worked for the following six years to make Ford’s products winners.

K-K had a ‘Special Vehicles Activity’ whose brief, described in an undated Ford document was to ‘…engineer, build, test, develop, prototype and manufacture a complete vehicle, or any system or component thereof. It (further) has the ability to generate complete product proposals and coordinate the total program with respect to manufacturing. In addition to offices at Engineering Building 3 and Ford Division General Office, Special Vehicles activities utilises Kar-Kraft Inc, contracted solely to Ford Motor Company…’

In short K-K had a brief broad enough to build one car or a limited production line such they did to construct the Boss 429 Mustangs when Bunkie Knudsen tasked them to do so. Crucially, they formed the link between the race teams (such as Shelby and Bud Moore in a Trans-Am context) and divisions back at Ford. In this way the race teams got access and input from the Ford departments which looked after engines, gearboxes, suspension, aerodynamics, computers and electronics.

Mustang 1

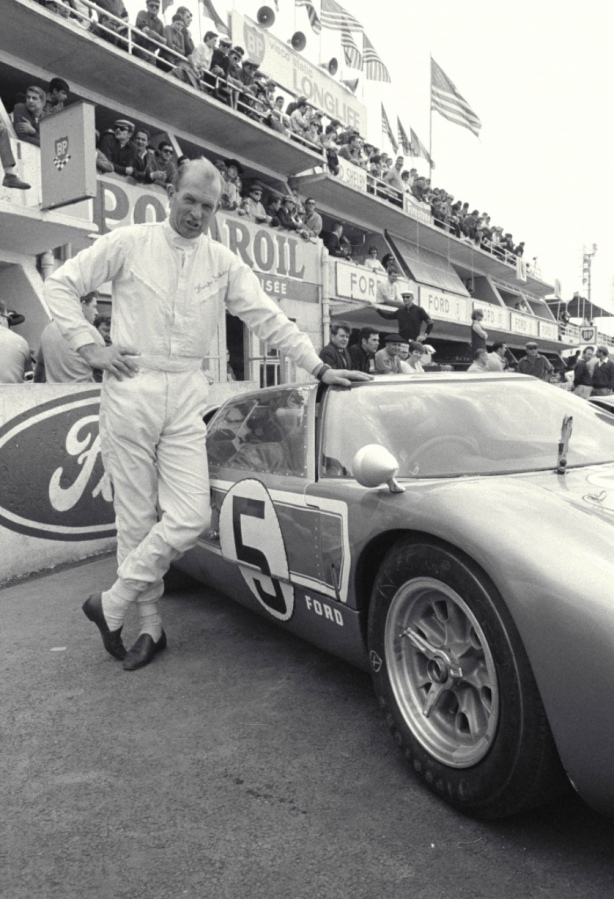

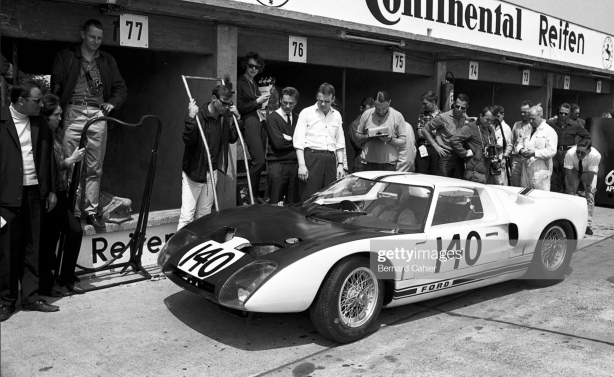

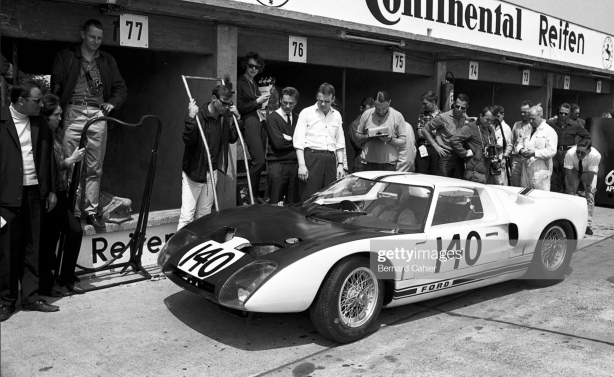

Ford GT40 race debut, FAV Slough built, Nurburgring 1000km 31 May 1964 Bruce McLaren (up) and Phil Hill. John Wyer behind the car head down taking notes

Ford GT Mk2, Ford Proving Ground Detroit June 1966 (Getty)

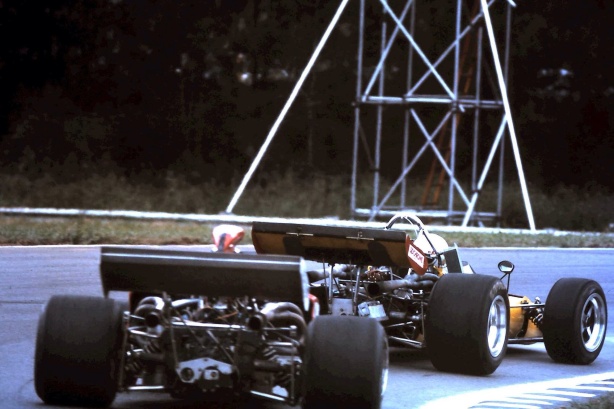

By the time K-K were given the 1968 and onwards Mustang programs their Ford Mk2 and Mark 4’s had won Le Mans in 1966 and 1967- the J-Car program was not so successful. K-K’s first job, which they did rather successfully was to marry the GT40 chassis and componentry with the 427 ‘Big Block, NASCAR engine and in the process developing the K-K transaxle, stuffed with heavy-duty ‘Top Loader’ gearsets, together with Pete Weismann and relentless testing by K-K and Ken Miles and Phil Remington from Shelby, they soon had a race winner. The Mark 2 first won at Daytona in early 1965 and of course triumphed in the famous 1-2-3 form finish at Le Mans in 1966.

In fact one of the reasons K-K ‘copped’ the Mustang program is that with a stroke of the rule-makers pen 7 litre cars were banned from the International Championship of Makes with effect 1 January 1968, so K-K’s primary race programs were at an end, they had resources available. And so it was with the death of the big-beasts, that the ‘original’ GT40 5 litre finally, long in the tooth, had its place in the Le Mans sun in 1968 and 1969 with John Wyer’s JW Automotive the most successful team to race these cars, two wins on the trot at the Sarthe using chassis ‘1075’.

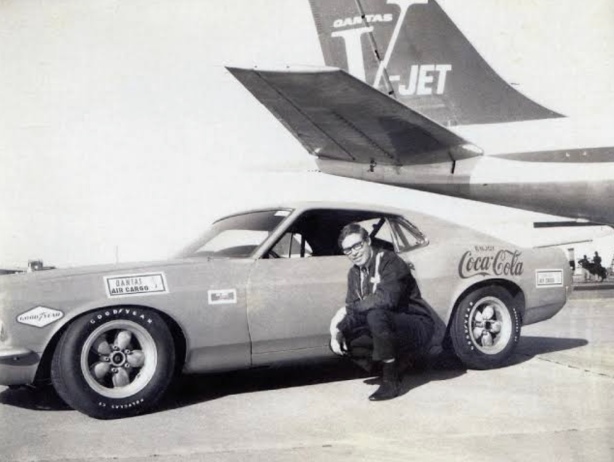

During 1968 Allan Moffat got his chance with K-K ‘I was sitting in the Ford cafeteria with Peter Quenet, when Roy Lunn came over and said “What are you doing?”, and I said “starving to death”, so he said why don’t I go and work for Kar-Kraft. It was really one of those very fortuitous, fateful lunch meetings that happen to people from time to time. I worked right through Christmas, but their first cheque didn’t arrive until March. It was for $5000 and I think it all went straight to American Express’ Auto Action recorded.

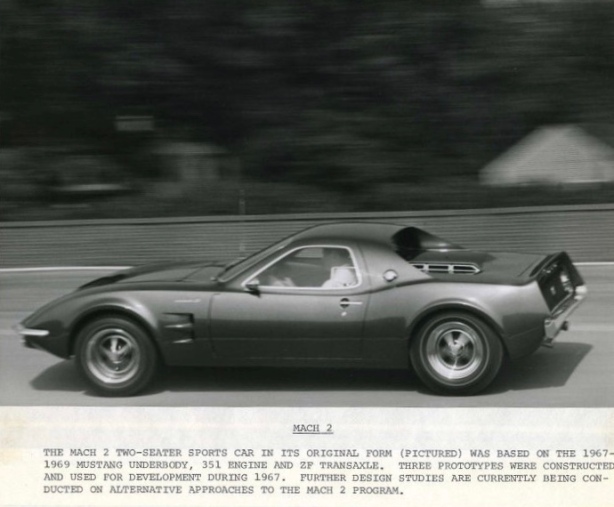

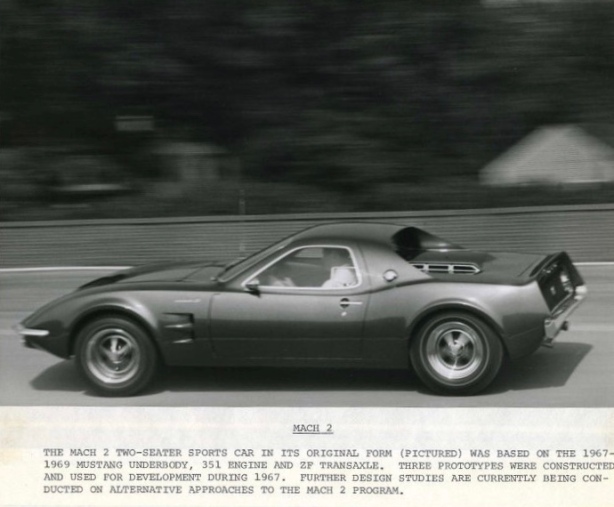

Moffat worked on the Mach 2 Mustang- a mid-engine Corvette beater with IRS and a fibreglass body (which ultimately became the Ford engined De Tomaso Mangusta) the 1968 Trans-Am Mustang developments and the 1969 Trans-Am.

When K-K took over the Mustang program they built two new 1968 Coupes which Shelby developed and raced- the two cars raced at Daytona and Sebring were modified 1967 Shelbys. Moffat got his opportunities with Shelby early in the season given his involvement with K-K albeit the Shelby Racing Co staff would have been well aware of his race record in recent years.

Where I am going with all of this is Moffat’s journey from Lotus Cortinas in 1964 to the first meeting at Sandown in May 1969 when he raced his Kar-Kraft/Bud Moore Trans-Am, so a look-see at the 1968 Kar-Kraft/Shelby cars, given the carryover of some key components to the ’69 Trans-Am is relevant to the car we all came to know and love in Australia. And there is a Bob Jane Shelby twist in all of this too as many of you know.

The primary differences between the 1967 and 1968 Mustang notchback racers may have appeared minor, just sheetmetal, but the ’68 racers were mechanically much closer to the ’69 Boss cars than they were their ’67 notchback predecessors, that was in part due to rule changes between the 1967 and 1968 seasons.

The 1968 rules allowed greater freedoms than the Trans-Am’s first two years. For over 2 litre cars, a maximum engine capacity of 305cid was allowed regardless of the size of the original engine fitted. Wheels could be 8-inches wide and arches flared to accommodate them. Full interiors were no longer mandated- and most cars used roll cages to increase the vehicles torsional rigidity with obvious performance dividends. Pieces were removed, trimmed or drilled to reduce weight- this search for weight reduction eventually led to acid-dipping chassis as well as the parts attached to them- this became an epidemic really and is a story in itself, but not for now- the minimum weight was 2800 pounds.

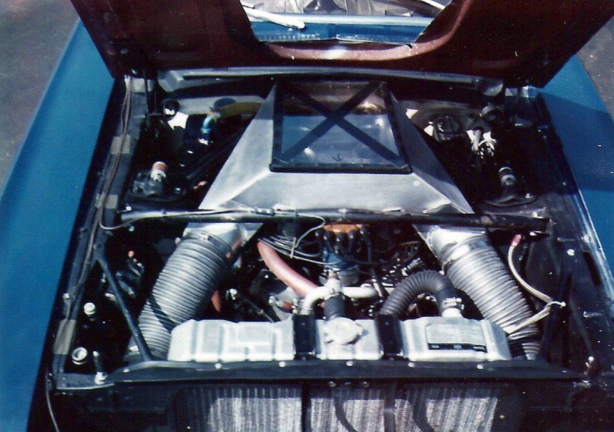

Four-wheel disc brakes were allowed even though no such option was available on the specification sheet from any US manufacturer of a production car. Kar-Kraft used massive Lincoln calipers and rotors on the front whilst Kelsey-Hayes four-piston calipers (used on the 1965-1966-1967 Shelbys) were used at the rear. k-K special hubs allowed the rear ends to be fully-floated and suspensions employed K-K Watts linkages, narrowed rear springs were used and double-adjustable Koni shocks. Fuel cells were made mandatory from May 1968 with special refuelling rigs deployed- Penske’s team were aces at using trick rigs to speed up pitwork and forced other factory teams to follow.

Two ‘Shelby Racing Co’ cars were entered for each event, a total of four team cars were used during the year- two were new cars based on 1968 Mustangs and two were rebuilt 1967 Shelby team cars, the latter pair were the duo of cars raced at Daytona and Sebring as covered above. For the sake of completeness another new chassis was set aside for Shelby’ use but was not built up as a racer, however it was eventually assembled as such some years later.

Jerry Titus 1967 Shelby Mustang notchback during the Mission Bell 250 at Riverside in September. Not quite as ‘butch’ as the ’68 cars with more tyre and ‘flare’ (J Christy)

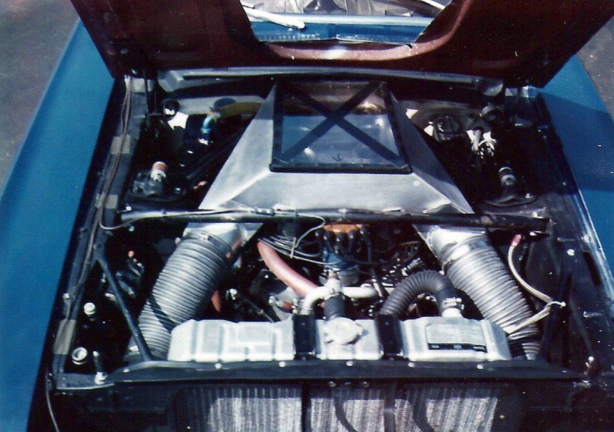

The dreaded 1968 302 Tunnel Port engine- cylinder head (unattributed)

Riverside late 1968 season engine test, one of the ’68 Shelbys at Riverside (F Hernandez)

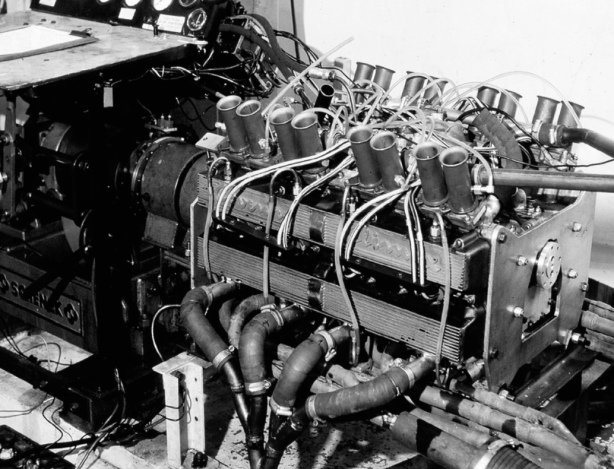

The ‘famous’ late 1968 engine test is the 1969 shootout between the Tunnel Port, Gurney-Weslake and Boss 302 engines fitted in a ’68 Shelby- but look closely and it appears a bunch of Webers smiling at us. Charlie Henry’s book says that K-K tested a G-W manifold with Webers (exactly as used on the JW GT40’s with a bulge to give the carbs breathing space- in long distance 24 hour spec, fitted in a GT40 the engines in period gave a smidge under 500bhp. ‘Whilst the carbs provided data they were illegal in SCCA Trans-Am’ but legal in Oz where Webers were Moffat’s instruments of choice (F Hernandez)

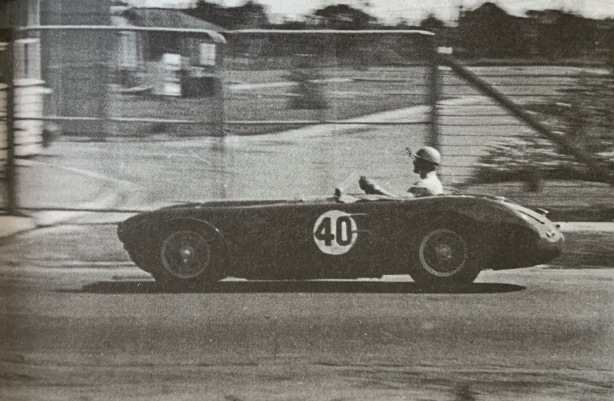

As related earlier, Jerry Titus won the first 1968 Trans-Am round at Daytona run in conjunction with the Daytona 24 Hour, he finished fourth behind three long-tailed Porsche 907 Lang-Hecks.

The engines used at Daytona were Shelby Racing Co built Tunnel Port V8s. From race four of the Trans-Am, the Lime Rock round and onwards, Ford decided that all engines for Shelby would be supplied directly from Ford’s engine foundry- that is, engines assembled and built by ‘Ford Engine Engineering Special Vehicles’ were shipped in crates to Shelby for installation into the cars.

After each race they were removed and shipped back to Ford for disassembly, inspection and evaluation- this proved a disastrous decision which cost Ford any chance of winning the 1968 championship. So frustrated was number one driver Jerry Titus, that he formed his own team to race Pontiac Firebirds starting with effect the final Riverside round.

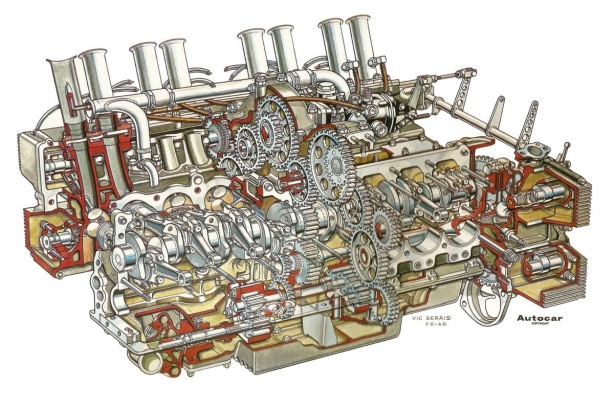

FoMoCo’s new 302 ‘Tunnel-Port’ engine was the secret weapon which would bring a third Trans-Am Championship on the trot, they hoped. A refinement of the 289 Hi-Performance V8, the primary change was to the cylinder head design. The 289 heads tended to be restrictive and only so much extra performance could be gained through porting and polishing- the new design was based on Ford’s NASCAR 427 heads.

The intake ports were straight instead of snaking around the pushrods- the pushrods went through the centre of the ports, giving rise to the name ‘Tunnel-Port’. This also allowed larger valves to be used, an extra eighth of an inch of piston travel was included, bringing the total displacement to 302 cubic inches. The block was strengthened and used lovely four-bolt main bearing caps, the whole lot was topped off with an aluminium dual quad carburettor intake. Shelby dyno sheets showed power outputs of 440 to 450bhp albeit this was produced very high in the rev range which became the cause of great, consistent reliability problems- apart from being power and torque curve characteristics unsuited to the demands of road racing.

Oiling problems plagued the engines the entire season- hardly a race weekend went by without one, usually more engines turning themselves into scrap metal. Some races were described as ‘six engine weekends’ because two engines would blow in practice and the race. At one point Shelby asked Ford if the team could go back to building their own engines- Ford’s answer was a succinct ‘No’. For the record, Shelby engines won two out of the four races in which they built the engines- Daytona and Riverside whereas Ford’s score was one from nine- Watkins Glen.

(L Galanos)

A month or so after Daytona (where this long piece started) the Shelby team headed from California in the direction of Florida, Sebring for the second race of the season on the 23 March weekend.

There, Moffat again shared the car with Horst Kwech where they qualified Q22, the Titus/Bucknum duo Q16 with the pair of Penske Camaros of Donohue/Fisher Q13 and Fisher/Welch/Johnson Q17.

Up front the race was won by the Siffert/Hermann 2.2 litre, flat-8 Porsche 907 from the sister car of Elford/Neerpasch whilst third outright was the Donohue Camaro from the Fisher machine, then the Titus/Bucknum Mustang with Allan and Horst one of the many tunnel-port’ engine DNF’s for the year.

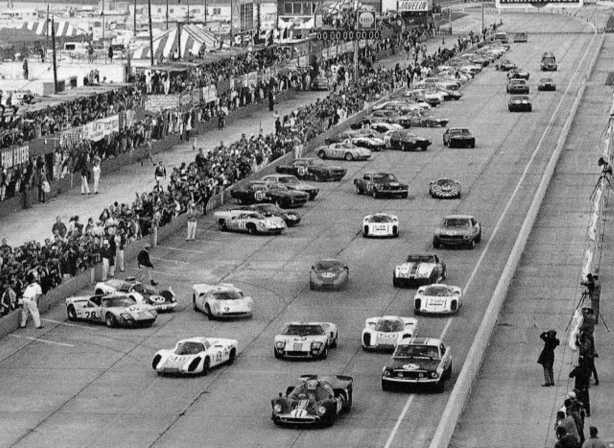

Louis Galanos commented about his photo above ‘I can’t help but smile seeing this…photo…from the Sebring 12 Hour…After the Le Mans style start cars are coming down the front straight three and four abreast. David Hobbs in a Gulf GT40, Ludovico Scarfiotti in a factory Porsche 907, Allan Moffat in a Shelby Mustang , Scooter Patrick in the Lola and so on…’

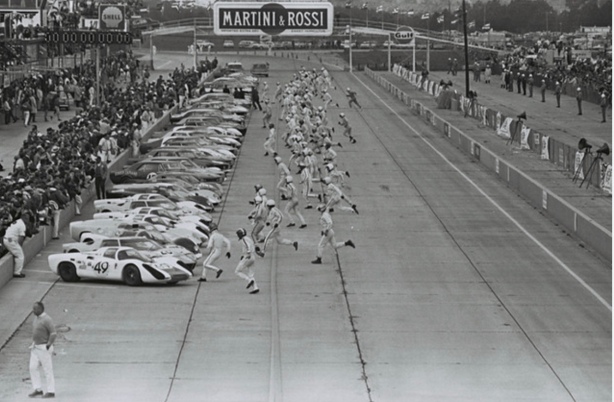

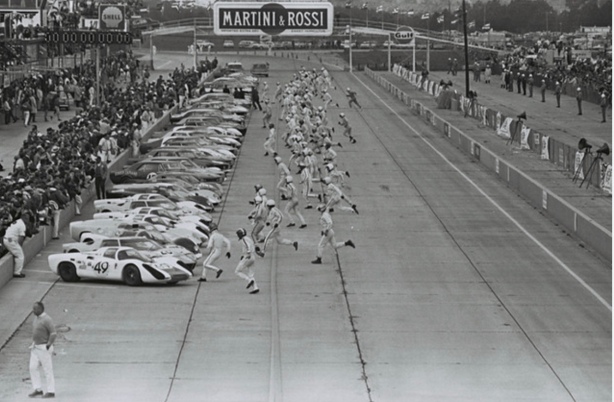

Checkout the amazing sequence of photographs below which shows just how quick away Jo Siffert was on pole and Allan Moffat down in Q22- Usain Bolt twitch fibres and all that, and no seat belt buckle done up I guess.

(D Friedman)

Drivers all in a pack, Moffat does appear to be making ground here, wherever he is, he comments in his autobiography written with John Smailes about his lack of training down the decades so we was not an elite level runner.

(D Friedman)

Siffert and Moffat- surely both have ignored belts, and critically their engines have answered the starter button immediately on call.

(D Friedman)

Jo is gone- out of shot whilst Moff is about to be swamped.

(unattributed)

From the off you can see how Moffat takes the Mustang wide knowing the zippy mid-engine rockets are going to cannon in his direction with the #11 Lola T70 Mk3B Chev of Mike de Udy (above and below) nearly driving him right into the wall- did he have a rear view mirror after that I wonder?

#28 Ickx/Redman and #29 Hawkins/Hobbs are the JW GT40’s #51 is the Ludovico Scarfiotti Porsche 907, #56 is the Foitec/Lins Porsche 910 and #42 the Bianchi/Grandsire Alpine A211 Renault and the rest.

(L Galanos)

(unattributed)

Titus and Bucknum made a strong showing at Sebring where they finished third in the Trans-Am class, behind the two Penske Camaros despite thirteen pit stops. The cars used Shelby prepared Tunnel Port V8s and cast iron Ford top-loader four-speed close ratio gearboxes, after this race aluminum Borg Warner T-10s were used.

Moffat all loaded up before the race, Titus machine alongside- ‘Shelby Racing Company’ decal on the B-pillar- and in action at Sebring below

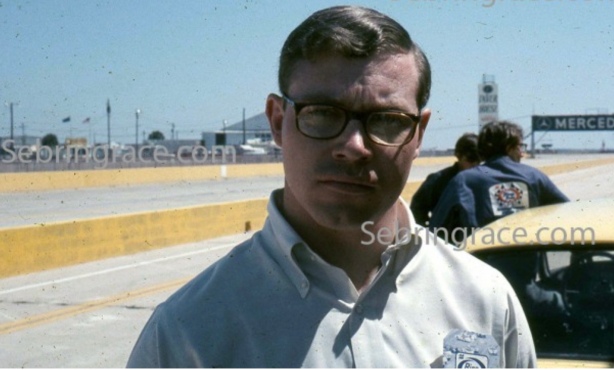

Context for being given the Daytona and Sebring drives are Moffat’s performances in the previous two years and in particular the late 1967 Mustang and Mercury drives together with the KK testing role ‘…I was in the Ford fold, totally visible’ Moffat related to Smailes.

Allan was competing for the second seat in the Shelby team against Kwech- Titus was the number one and Bucknum had indicated he didn’t want the drive for the year.

At Daytona ‘In the race for the Shelby Ford works seat, score one for H Kwech. You never want to be at the wheel of the car when it breaks and he’d neatly handballed that honour to me. A month later at Sebring I broke my golden rule. When the flag dropped I was away, leading (the class) for the first hour until I was overhauled by Mark Donohue…When I handed the car back to Horst it was perfect, but, with one lap remaining of his long stint, the engine blew. At least he hadn’t been able to get me back behind the wheel before it broke.’

In due course the two Shelby sprint Trans-Am drives for 1968 went to Titus and Kwech.

Allan Moffat would return to Sebring a few years later at BMW’s invitation.

He joined Hans Stuck, Same Posey and Brian Redman in a BMW 3 litre CSL to victory in the March 1975 running of the classic from the Dyer/Bienvenue Porsche Carrera RSR and the Graves/O’Steen/Helmick similar car.

(unattributed)

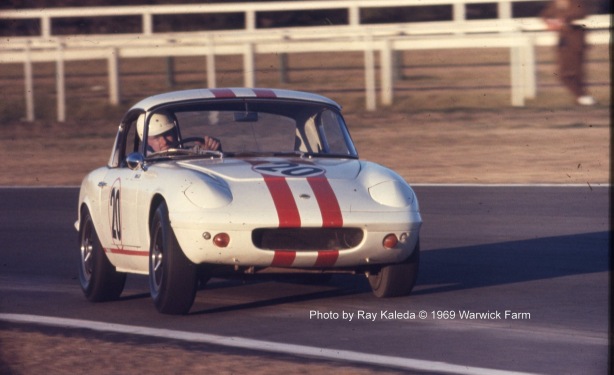

After the conclusion of the two big international races in the US at the outset of the 1968 season Moffat was at a loose end- he still had his K-K testing gig but all the Mustang Trans-Am race seats were taken, Ford had lost interest in the under 2 litre class and in any event the Porsche 911s (admitted by the CSI as Group 2 touring cars) were dominant. More Cortina racing wasn’t going to take Allan forward, the Mercury program was at an end too- Ford would not make the mistake of splitting its resources and racing against itself again. As Charlie Henry wryly observed ‘Cougar never gained admittance to the Ford Motor Company “racing clique”. Ford wanted a performance oriented Ford to win, not a division with a luxury car reputation.’

The balance of the 1968 Trans-Am season unfolded like this.

Parnelli Jones joined Shelby at War Bonnet for the third Trans-Am round, qualifying on pole, but by the lap 7 Donohue’s Camaro was firmly in control up front- Jones was third with Titus out on lap 46 with a popped Tunnel Port V8. At Lime Rock, over the Memorial Day long weekend, Titus was second with the ‘guest car’ driven by NASCAR stockcar racer David Pearson, he retired on lap 22 after being black-flagged for leaking oil onto the track, the engine was consuming the slippery stuff faster than the crew could pour it during pit stops

shelbytransam wrote that ‘Things went from bad to worse for the Shelby team after that. Roger Penske’s Sunoco Camaro, driven by Mark Donohue, continued to run like a freight train while the Shelby cars faltered at every turn. Titus finished second at Mid-Ohio but teammate Horst Kwech, in #2 car blew the engine on the first lap. At Bridgehampton, the team’s semi-tractor trailer was involved in an accident on the way to the track and crushed the roofs of both cars. They were repaired as soon as they arrived but Kwech blew during the Sunday morning warm up before the race started and Titus went out with a broken suspension. At Meadowdale, in Illinois, Kwech finished eighth and Titus came in eleventh. Titus finished fifteenth at St. Jovite in Canada whilst Kwech blew his engine. At Bryar, in New Hampshire, Titus finished tenth and Kwech again blew an engine. Donohue won that race…effectively clinching the championship right there.’

Whilst all of this race excitement was going on, Moffat still had his Kar-Kraft testing duties but he was of course frustrated about not racing but his career was about to change direction again- in a pivot back to Australia.

Entrepreneur/racer Bob Jane’s first 1965 Mustang met its maker in an accident at Catalina Park in New South Wales’ Blue Mountains that November, he was lucky to walk away from the accident which is covered in this article here; https://primotipo.com/2020/01/03/jano/

Undeterred, he soon acquired a 1967 Mustang GT390 which was progressively modified, inclusive of the use of a small block V8 to get a car which handled as well as Pete Geoghegan’s locally developed (by John Sheppard) Mustang GTA- but it didn’t matter what the boys in his Brunswick HQ did, he still could not catch Big Pete. In fact the shortfall was Jane’s capabilities behind the wheel- Bob was no slouch of course, but he, like the rest of the competitor set were not on the same planet as the big, beefy Sydney motor dealer.

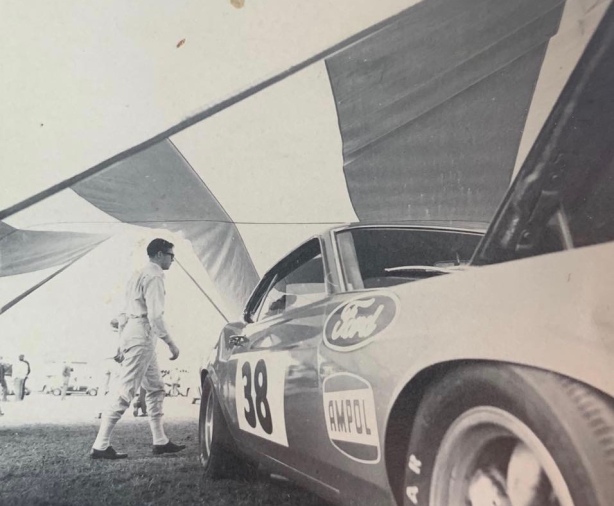

Bob despatched his long-time Team Manager, John Sawyer to the ‘States to find some goodies and know-how to try and bridge the performance gap between his and Geogheagan’s cars mid-year prior to the one race Australian Touring Car Championship to be held in Pete’s backyard- Warwick Farm, on September 8 1968.

John knew Allan, looked him up in Detroit and sussed him as to who to talk to and contact in relation to all the trick Ford bits, Allan helped out with introductions, explaining who John and Bob Jane were and how they fitted in, and assisted in getting all the components they needed, and then some.

Allan also set up the contacts with Shelby to acquire an ex-works 1968 car for Jane to use in 1969 and beyond- lets come back to that in a little bit.

Sawyer and Moffat spent plenty of time together, John soon got to understand Allan’s plight- race drive unavailabilty and all the rest of it. John contacted Jane about Moffat’s plight and soon he was offered a job with the Bob Jane Racing , acting as a go-between for the Mustang purchase project. Although nothing was documented, Allan understood that, in return, he would get to drive the older Mustang ‘GT390’ when the new car arrived in Australia.

Happy days indeed! Or so it seemed.

Bob Jane in the GT390 early days @ Warwick Farm in 1967 (unattributed)

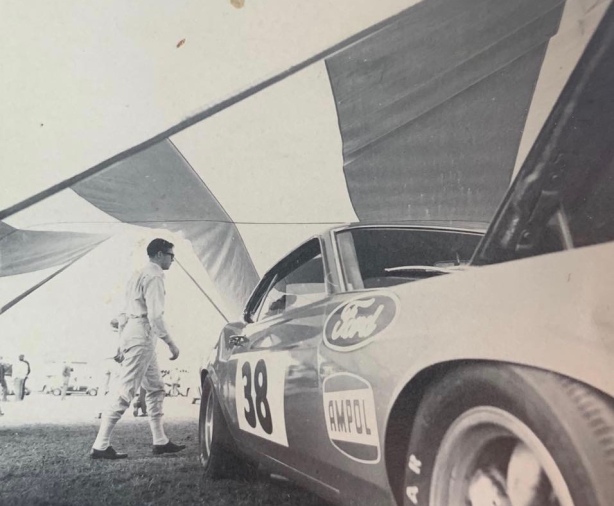

Horst Kwech, Shelby Mustang, Riverside, on the way to a win in late 1968- this chassis was soon to become Bob Jane’s car (unattributed)

Bob Jane, Mustang, Hume Weir, circa 1970 (D Simpson)

Jerry Titus finally broke Donohue’s winning Trans-Am streak at Watkins Glen in August 1968 when the Camaro lost its brakes three-quarters of the way through the race. Dan Gurney was guesting in the other Shelby Mustang and retired with a blown engine. Donohue came back at Continental Divide Raceway in Colorado, finishing back in front- Titus and Gurney were both out with blown engines- this was the meeting after which Jerry announced that the next race, Riverside, would be his last in a Mustang, then he was off to campaign his own Pontiac Firebirds- Shelby were very sad to see him go of course.

By September 8, with both Donohue and Titus out at Riverside and Horst Kwech a Shelby Mustang race-winner, his car fitted with a Shelby pepped Tunnel Port, Allan Moffat was back in Australia, racing of all things Bob Jane’s Tasman 2.5 litre single-seater over the 15 September weekend…

On Horst’s race-winning weekend Bob Jane contested the ATCC race at Warwick Farm. Geoghegan started the race from pole and won after Beechey and Jane touched on the first lap- Bob retired with Geoghegan winning from Darrell King’s Morris Cooper S and Alan Hamilton’s brand new, just arrived in Oz, Porsche 911S/T.

Bob Jane Racing had a swag of drivers on its books by this stage of 1968.

John Harvey came very close to meeting his maker after a rear-upright failure in Bob’s new- just bought off Jack Brabham, Brabham BT23E Repco V8 dumped him amongst the scenery at Mount Panorama during the traditional Easter Bathurst Gold Star round. Harves was incapacitated with a long convalescence for the rest of the year whilst the shagged Brabham was repaired by Bob Britton in Sydney.

With Harvey indisposed, a three car team (Brabham, Mustang and Elfin 400 Repco sports-racer) and contractual commitments to Shell, Jane contracted two young Melbourne up-and-comers- Ian Cook and Bevan Gibson to have some drives, the story of the Elfin and these two are told in this article; https://primotipo.com/2018/04/06/belle-of-the-ball/

So, by the time Moffat arrived in Melbourne Sawyer and Jane had four drivers and three cars.

Ian Cook, with a solid background in ANF1.5 single-seaters, raced the repaired BT23E to fourth in the Gold Star round at Lakeside in late July during Kevin Bartlett’s dominant 1968 Gold Star year aboard Alec Mildren’s Brabham BT23D Alfa Romeo Tipo 33 2.5- the team missed the following Surfers Paradise round in late August with Moffat having a run at Sandown.

Whilst Moffat now had heaps of touring car experience- including ‘Big Car’ stuff as Frank Gardner liked to call them, his exposure to the more rarefied world of single-seaters was limited to a race or two in a Brabham BT15 Ford twin-cam in the US in 1967.

Sawyer and Moffat set off across Melbourne from Jane’s race base in Brunswick to Sandown Park- a circuit on which Moffat had always been quick, but his weekend was over almost before it started after an accident when a rear tyre parted company with its rim as he accelerated up the back straight. Game over before it had even begun.

Towards the end of the year, on 24 November he drove the Elfin 400 Repco ‘620’ 4.4 V8 sports car (below) to two wins in the Victorian road Racing Championships meeting at Phillip Island.

This shot and the one below are of AM and John Sawyer in the backlane behind Bob Jane Racing HQ in Brunswick, Melbourne just before heading off for Sandown in 1968. Brabham BT23E Repco ‘740’ 2.5 litre V8 ‘Tasman Formula’ car (B Nelson)

(B Nelson)

Moffat in the Jane Elfin 400 Repco ‘620’ 4.4 V8, Phillip Island, November 1968 (R Bartholomaeus)

Horst Kwech’s Riverside Mustang win was the team’s third victory of the year, the last race of the season, at Kent, Washington saw Donohue win while Kwech and Peter Revson both failed to finish. Revson’s engine blew and Kwech crashed on the tenth lap. Titus seemed to console himself by talking pole in his new Firebird although he retired with engine problems on the lap 43.

Moffat’s work was very well done- Jane bought the car raced by Horst to victory at Riverside- VIN#8RO1J118XXX was the very last of the 1968 K-K/Shelby cars built and had only raced three times in the hands of Dan Gurney, Peter Revson and Horst- happily for both Jane and Moffat it was soon on its way to Australia with our man expecting to race the hand-me-down GT390 in 1969 whilst his team-owner raced the near new car, on the face of it the pair were a strong combination for the ensuing year.

David Hassall wrote that the association with Jane nearly resulted in Allan’s first drive in the Bathurst 500- at one stage in 1968 it appeared that Jane would enter the race in an Alfa 1750 GTV with Moffat as co-driver, but it didn’t eventuate.

Allan stuck it out at Jane’s until one day in January 1969 when Bob went through the workshops- the Bob Jane Corporation headquarters was in North Melbourne several suburbs away from the race workshops in Brunswick, so Jane- running an empire at that stage involving new and used car dealerships, a car wholesale auction business and Bob Jane T Marts, a national franchise- would not have seen Moffat regularly in the normal course of running his large enterprise.

Bob said he didn’t think things were working out too well, suggesting they call it quits. Allan was thinking of leaving anyway, so that was it. He certainly wasn’t sorry to leave Bob, but he was also fired up with strong feelings about the way things had gone.

For the umpteenth time in his career, Moffat had no money or income or a drive.

At that point, with a new season underway, Moffat played the best card he had- he write to the most senior Ford executive he knew from his years in the states, he related to John Smailes ‘I wrote directly to Jacque Passino, the head of all motor sport for Ford. Like most of the Ford top brass at the time, Passino was a dyed-in-the-wool car guy, but not necessarily a motor racing enthusiast.’

‘The…motor racing brief was another step on Passino’s career ladder and he intended to carry it out well. The thing is, he had the authority to keep his promise. I just thought I had to have a go. My letter to him got through to his secretary, a feat in itself, and I was granted an appointment. I guess I had some credibility, being the outright winner of the third-ever Trans-Am race in one of his products must have stood for something, and backing up as a driver in his works team as well as a Kar-Kraft test pilot maybe put me on his radar. But I seriously doubted it.’

‘My grandfather always taught me never to sit down in anyone’s office unless they invited you. Passino was a fearsome guy, beautifully dressed, with prematurely greying hair and strong steel glasses. He didn’t ask me to sit. I explained my case. I was a Ford man through and through. I had unfinished business in Australia – to win the national title – and a Cortina was no longer going to do it for me. I concluded by asking: “Are you able to help with a car?”

‘He said: “I don’t know where the cars are. Give me a couple of days and I will see what I can dig up for you.” He asked me where I was staying – a motel down the road, which he passed every day on the way to the office. It was only when I left his office that I reviewed what he’d said; “I’ll see what I can dig up for you.” Not just “I’ll see what’s available”, but “for you”. Those were the two key words.’

‘I hightailed it back to the motel and briefed the front desk guy. “Sometime, I don’t know when, I am expecting a visitor or a phone call. I won’t be leaving my room until then”. I arranged for room service for all meals – not exactly a feature of the house. And I waited.’

‘On the fourth day, the longest four of my life, the phone rang. It was Passino himself: “Have you got enough money to get to Spartansburg (Bud Moore’s workshop)?” I said, “Only just”. He said, “There’s a car waiting for you”.

‘There was no mention of payment, but I figured that was to come. For the 1969 Trans-Am series Ford was having a big go. Through Kar Kraft they had built seven incredibly special Ford Mustangs, the Boss 302s. Three each were to go to Ford’s two works teams – Carroll Shelby and Bud Moore. The seventh would go to Smokey Yunick’s NASCAR team. Their value was incalculable.’

‘I had no expectation even of touching those cars. My goal had been to see if I could buy, at the cheapest possible price, one of the now-redundant 1968 cars. I was at Bud Moore’s workshop the next day and he wouldn’t look me in the eye. I thought, Who are you to be upset? I’ve come to buy used stock. He walked me into the workshop and there, sitting abreast, were three new Trans-Am Boss 302s, each still in their grey undercoats.’

“The middle one is yours,” he said.’

‘Jacque Passino had done what probably nobody else in Ford could do, with the possible exception of Henry II. With one word, he’s made one of the magnificent seven mine. At no cost. No cost at all. I didn’t know why then and I don’t know why now. There are theories. Ford Australia was a favoured outpost of Dearborn. Maybe a favour was being offered way beyond me. Maybe, simply, it’s because I asked and someone liked me.’

Moffat’s car as he first saw it at Bud Moore’s Spartanburg workshop in South Carolina late 1968. The thing that is not clear, despite plenty of research and I suspect differs, is the degree of completion of each of the Trans-Ams at Kar-Kraft before handover to the race teams (AMC)

Moffat taking some lucky punters- members of the press no doubt for a whirl of Sandown, probably on the Thursday prior to the May 1969 Southern 60. Note the Fairmont Wagon alongside, a good family bus of the time (AMC)

Moffat’s primary job when he returned to Australia with the Mustang was as Ford’s #1 driver of Series Production (Bathurst) cars- here he is during the 1972 Phillip Island 400km aboard an XY Ford Falcon GTHO Ph 3- he won from Brock’s XU1 and Gibson’s HO. In the background is one of the two works Datsun 1200’s of Evans or Roxburgh/Leighton (I Smith)

‘When I returned to Australia that year I was immediately drafted into Ford’s series production touring car team and became Number One. So perhaps there was a grand plan in which the Mustang was the best incentive ever. I don’t think I’ll ever know. A lot was happening in Australian motor racing.’

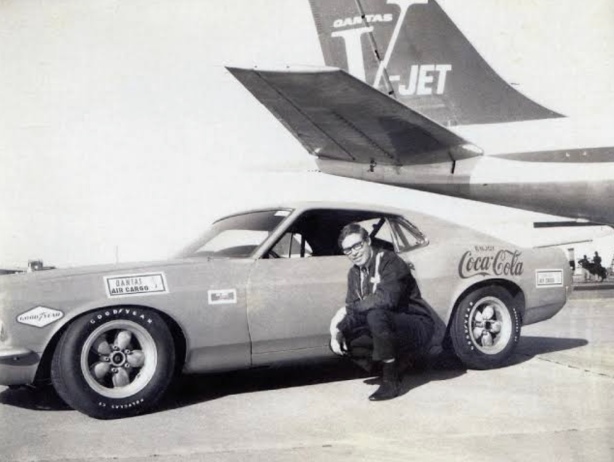

‘For the first time the Australian champion would be decided in a series of five rounds. Two rounds of the championship would have already been held by the time of my return, one won by Pete Geoghegan and the other by Bob Jane, both in Mustangs. Even if I won the last three races, if Pete came second, he would still take the title on accumulated points. The second major change in motor racing was the emergence of sponsorship on cars. The Mustang may have been free but I needed money, lots of it, to run it and this was the opportunity to provide a big-name sponsor with exposure in a brand-new medium. Coca-Cola was interested. My proposal had gone to Victoria and landed on the desk of its visionary marketing manager, David Maxwell. My Coke backing was, in the context of the company’s other involvements, a pretty cheap sponsorship. I had two reasons to be grateful to him. The other was Pauline Dean’- who was to become Allan’s first wife.

But lets not get ahead of ourselves, whilst the specifications of Moff’s iconic car can almost be cited by Australian enthusiasts- even open-wheeler nutters like me verbatim, some of you may not be quite so familiar with these seven, in particular six special racing cars…

Lets not forget before we embark on these 1969 Trans-Am cars that the 1968-1970 Mustang chassis were similar enough that suspension components, chassis strengthening, engine packaging, fuel, cooling and exhaust system learnings of the previous two years were carried over into 1969.

These included but were not limited to heavy duty front axles (spindles), the floating rear axle, brakes and Watts linkage- the 1969 car was not ‘clean sheet’, the 1968 program generated useful aerodynamic information and late in the year more reliable engines, but even with the upgrades the 1969 Mustangs were still working to improve brakes, low RPM response, tyres and weight- by 1970 the machine’s shortcomings were resolved and the Trans-Am championship went to Mustang.

Prototype K-K 302 Trans-Am towards completion- the hood scoop didn’t make it onto the race or road variants, date unknown (F Hernanadez)

Stunning image of ‘the recently completed 1969 Kar Kraft prototype’ VIN unknown, this batch of photos were in an envelope Fran dated 14 December 1969. It’s a racing car but note the standard of finish- panel fit for example. Blue cars suggests its destined for Shelby. Wheels are American Racing ‘Torq Thrust’. Stunning motorcar (F Hernandez)

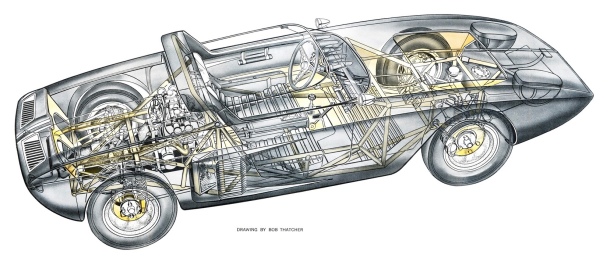

At the commencement of the Boss 302 race program, K-K built two prototype Trans-Ams for evaluation by the Shelby Racing and Bud Moore Engineering race teams. In mid August 1968, shortly after commencement of 1969 Mustang production, and with race homologation in place, an internal factory order was placed for two ’69 428 Cobra Jet fastbacks, less paint, sealant or sound deadener. The cars were delivered to the K-K’ workshop Haggerty Street ‘shop, from Ford’s River Rouge Complex and then completely stripped and rebuilt to Trans-Am race specifications under the supervision of K-K chief designer/engineer Lee Dykstra.

After completion, with conversion taking three weeks, one of the cars was given to Bud Moore whilst the other was retained by K-K.

Initial testing of the first prototype was carried out by K-K at Michigan International, after that the car was sent to Engine Engineering at the Dearborn Proving Grounds. That group used it to develop a fix for an oil starvation problem in the front-sump oil pan- a K-K design ended up as the oil pan of choice. Ford engineers, working closely with the Shelby and Moore race teams used these prototypes to conduct intensive race track engine evaluation (see engine specs) and chassis development work over several months.

During the engine selection tests at Riverside in late 1968 the engineers, technicians and drivers also worked on spoilers, ride height, springs, roll bars and other suspension components. A Shelby fabricated adjustable rear spoiler allowed the group to assess downforce/drag trade-offs- a front air dam assisted in getting the front to rear balance right.

The Trans-Am did find its way into the wind tunnel but not until July 7 to 18th 1969 when Lee Dyksta and Mitch Marchi tested a 3/8 scale model of the car in the University of Maryland tunnel- full scale tests were subsequently done in the Martin-Marietta wind tunnel in Marietta, Georgia.

When the specification for the racers was finalised, another internal order was placed at Ford’s Dearborn plant in December ’68 for seven more ’69 Mustang fastbacks to be assembled minus paint, seam sealer and sound deadener for Trans-Am race duties. Unlike the two KK-built prototypes which started out as R-code big block Cobra Jets, the seven new cars were no frills M-code (carrying sequential VIN numbers from 9F02M148623 to 9F02M148629) 351 V8s with four speed transmissions. Allan Moffat’s Trans-Am started as one of the cars in this special batch, carrying VIN No. 9F02M148624.

K-K picked the cars up at The Rouge and drove them the 5km to Haggerty Street.

After stripping, building and preparing the cars for racing the technicians installed the production parts removed from the cars earlier in the process, in essence each car was its own parts bin. One car was retained by Kar-Kraft, three were shipped to Shelby Racing Company and three to Bud Moore Engineering – Moffat’s car was one of the Bud Moore cars as related above. The sole fastback kept by K-K was a unique hand-built racer finished in a black with gold stripe paint scheme, for tuning legend Smokey Yunick to run in NASCAR’s ‘Baby Grand’ stock car series. The other six cars were built to Trans-Am specifications by the two race teams based on Kar-Kraft’s chassis design blueprints.

During a span of two years 15-18 cars came off the K-K surface plate, Charlie Henry wrote.

Alex Gabbard interviewed Fran Hernandez in the late eighties about the Mustang program, Fran recalled ‘I was officed at Kar-Kraft and running the program when we were doing all that (Trans-Am) racing. I had Bud Moore, Carroll Shelby and Bill Stroppe doing some racing for me, and also the independents. Ed Hull was the principal designer behind all my work as well as the design work behind the Mark 4 Ford that we ran at Le Mans (which won the race in 1967)’

‘Ed was a very prominent person overall in our racing program, body and chassis. He assisted me in designing my suspension system for the Trans-Am cars. Had we (Ford) stayed with racing in 1970, as progressive as we were, and well ahead of everybody else, 1970 would have been more of a “no-contest” than it was because we actually built no more chassis in 1970. ’69’s were the last cars we used. We were out of the picture. 1969 was our last big effort in racing. 1970 was when Ford got out of racing completely, the Le Mans effort shut-down, the Kar-Kraft effort went away, and our racing was gone.’

(AMC)

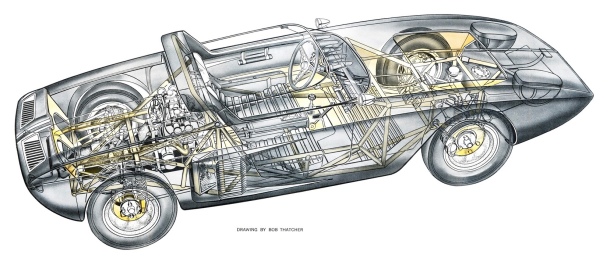

Chassis

FoMoCo were not going to be out homologated in 1969 as they had been in 1968 by Penske/General Motors.

The specialised design and fabrication which went into the six racers amounted to a very liberal interpretation of the Trans-Am regs- made possible by the ambiguous wording of the SCCA rule book, allowed Trans-Am race engineers a lot of creative freedom.

The first step in Kar Kraft’s chassis preparation was minimising weight.

Minimum weight of the 5 litre Group 2 cars in 1969 was 2900 lbs (1315 kgs). The aim was to build the cars as light as possible- and then bring them up to the minimum weight limit by positioning lead or steel ballast down low at chosen chassis points to move the car’s standard 55.9% front to 44.1% rear weight distribution nearer a 50/50 split.

The battery was moved from the engine bay to the boot, the engine was lowered discretely by around 50mm and moved back as far as the firewall would allow- this had the effect of lowering the car’s centre of gravity. The fuel tank was made out of two flanged halves (ie upper and lower shells) but a Boss 302 racer featured a much deeper bottom section than standard to drop the fuel load as close as possible to the road. This idea was replicated in the Bathurst ‘drop tanks’ used on the Holden Torana L34 and A9X racers of the mid 1970s.

The Mustang bodyshells were built without any weather sealing or sound deadening. K-K then removed any brackets not required for competition and either drilled holes in any remaining component or re-made it in aluminium right down to the internal window winding mechanisms which even had shorter crank handles to save weight.

Acid dipping was strictly outlawed but the practice was widespread in Trans-Am. It involved ‘drowning’ a metal component in an acid bath for a period of time to eat away a small amount of excess metal. Too much time in the acid vat left some components dangerously weak, hence the SCCA ban. It is not clear how much, if any, acid dipping the ’69 racers were subjected to. ‘Dipped’ or not, the fat farm program for the Boss 302 racers was effective and included significantly thinner window glass and bolt-on panels (bonnets, boot lids, door skins, guards etc) stamped from thin gauge sheet metal.

Technicians doing Trans-Am chassis structure work in the Kar-Kraft Merriman facility (F Hernandez)

Early’ish shot of Moffat’s car, probably Surfers Paradise in 1969, wearing Minilites by this stage- note in particular the guard flares as per text (unattributed)

Lessons learned from sedans at 200mph on NASCAR super speedways and Kar-Kraft’s own GT40 program made clear the performance gains to be made from good air penetration. This was prevalent in sedans with wedge-shaped silhouettes, Kar Kraft took things a step further by trimming 25mm from the height of the radiator support panel- the engine bay inner guards were then tapered down from the firewall on each side to match, this substantially lowered the front aerodynamic profile of a Boss 302 racer.

Hammer and dolly work created a flare for front guard to tyre clearance- technicians just pulled out, rolled over and flattened the inner lip of the guards. The inner halves of the rear wheel housings were also discretely moved inboard about 75mm on each side to provide adequate clearance for the 12-inch wide Goodyears- minimal flaring of the external wheel arch lips was permitted, this was achieved with the use a stamped metal panel, shaped as a flare which was fitted after cutting out a section of the rear guard- the stamped flare panel replaced the original metal.

To maximise torsional rigidity the shell was seam-welded and two sturdy braces were connected to the front suspension towers- one spanned across the engine bay between the two towers (which Moffat didn’t use) and another braced the towers rigidly to the firewall. The base of the towers used the substantial reinforcing plates fitted to the road going Boss 302.

Inside the cabin was a welded tubular steel roll cage ‘which blessed the Trans-Am Mustangs with the strength of armoured tanks’. Although the K-K cage designs of the Shelby and Moore teams differed in detail, they were fundamentally similar in that they extended beyond the cabin front and rear to integrate each suspension mounting point into the overall cage structure. This lack of chassis flex ensured accurate and consistent suspension tuning for optimal performance.

Rear suspension of Moffat car in recent times, note the oil coolers, Koni shock and roll bar beside the leaf spring on the right and the lower ‘Rose jointed’ lower end between the tyre and spring AMC)

Watts linkage and cooler (AMC)

(AMC)

Suspension

The front suspension subframe was notched about 20mm on each side where it bolted to the chassis, this had the effect of raising the sub-frame further into the car permitting a lower static front ride height. This left only 25mm of belly clearance above the road and was another gain in lowering the centre of gravity. It also explains why (in combination with the tapered front sheetmetal) a standard 1969 Mustang looks so high at the front compared to Moffat’s Trans-Am version!

Front suspension was based on the architecture of the road car but was considerably beefed up. Forged steel stub axles on thick cast uprights were mounted between strengthened upper and lower swinging arms, with revised pick-up points for geometry best suited to the lower ride height and the camber change characteristics of racing rubber. Adjustable rose joints and solid metal bushings featured with stiffer coil springs, adjustable Koni shocks, an adjustable anti-roll bar and a quick-ratio 16:1 steering box.

Rear suspension rules required the road car’s live axle/leaf spring arrangement be retained. As a result, Kar-Kraft’s superb ‘full floater’ nine-inch rear axle assembly (ie a full floater design ensured a broken axle would not result in a wheel parting company at speed) was located by race-tuned leaf springs and a pair of traction bars sitting directly above the springs and parallel to the road. These eliminated spring wind-up/axle tramp under hard acceleration and also served as rigid trailing arms for positive fore and aft axle location.

Lateral control of the rear axle assembly was assured by K-K’s beautifully fabricated panhard rod. Like the front end, the rear suspension was equipped with adjustable Koni shocks and an anti-roll bar. The static rear suspension ride height was around 90mm which, when matched to the 25mm front ride height explains why Kar Kraft’s Boss 302 racers looked like they were literally being pulled down onto the track surface by magnetic force!

The net result was a superbly balanced and responsive chassis.

Ford received so many enquires about modifications to Mustangs to Trans-Am spec they took the step of commissioning this booklet from K-K and offered it via the dealer network for $2 per copy- Google away, it’s online. Many of the goodies to modify the cars could be bought from dealers

Brakes, Wheels and tyres

Manufacturers were allowed to upgrade the braking system provided the components were sourced from the parent company or its divisions. The Kar-Kraft engineers used the same brake package as deployed in 1968. Ford Lincoln luxury, huge 11.96-inch diameter ventilated rotors and four-spot Kelsey-Hayes calipers. The road car’s rear drums were removed and upgraded with the standard road car’s 11.3-inch front disc brakes. External adjustment of front to rear brake bias was via a proportioning unit mounted under the floor adjacent to the rear axle.

The combination of Lincoln front brakes and Ford rears resulted in different wheel stud patterns front and rear- under Australian racing rules all four wheels had to be interchangeable, Moffat therefore had to re-drill his wheel centres so that they could be bolted to either end.

Trans-Am rules specified a maximum wheel width of eight inches, the Boss 302 racers rolled on a set of lightweight magnesium wheels, either the ‘American Racing’ rims on which Moffat’s car was delivered, later UK-built ‘Minilites’ he used and later again South Australian made ROH wheels. Tyres were 5.00 x 11.30 front and 6.00 x 12.30 rear.

Moffat’s car was delivered with a tunnel port 302- later Allan had two dry deck Boss 302’s- this is one, both engines exist and are with the car. Moffat used 7500rpm, 485bhp quoted with the Weber setup used in Oz (AMC)

Engine

The Boss 302 Mustang big breathing, high revving 5.0 litre small block V8 was one of the toughest small block pushrod production V8 ever to come out of Detroit.

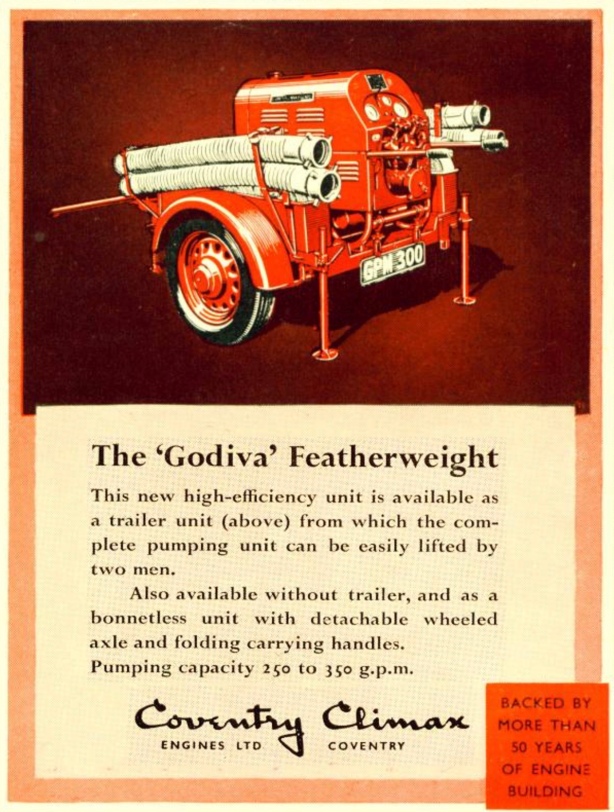

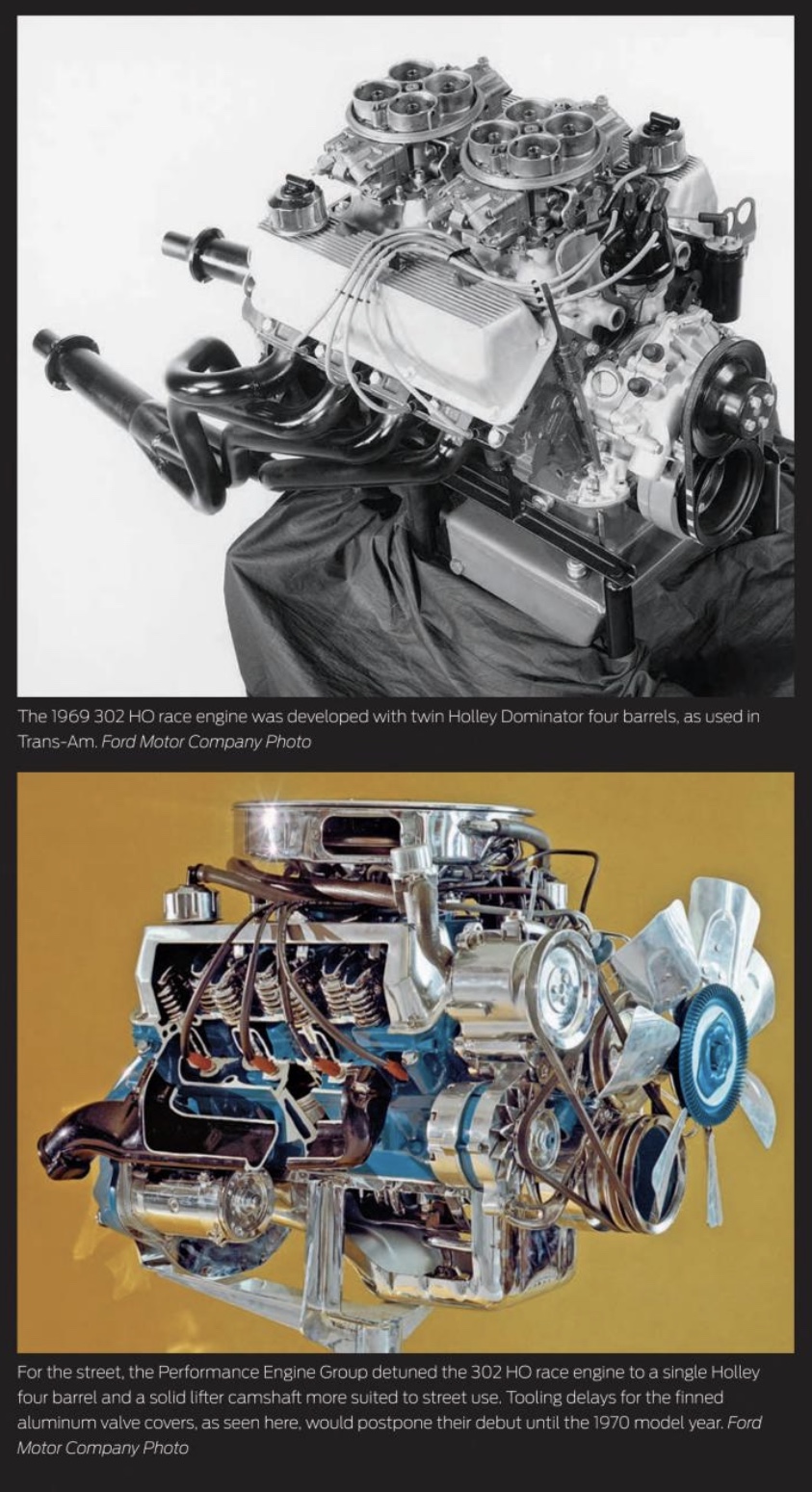

It evolved from the failure of the Tunnel Port 302 in 1968, in any event Ford never proved to the SCCA that it had produced the 1000 engines required for homologation so the temptation to make the thing (Tunnel port) work still had a legislative wrinkle or two to sort.

Ford’s Engine and Foundry engineers were faced with the challenge of cost effectively using existing ‘regular production’ engine components to meet the homologation challenge. After plenty of testing it was discovered that the cylinder heads from the new ‘Cleveland’ 351ci (5.8 litre) small block V8- to become such an important part of Australian motor racing- featured the same bolt pattern and bore spacing as the four-bolt main ‘Windsor’ cylinder block on the Tunnel Port 302, the mass-produced Cleveland heads were well suited to high performance applications and in many ways were superior to the Tunnel Port heads.

They featured a canted valve design (ie inlet and exhaust valves inclined towards the combustion chamber from opposite directions) which ensured unimpeded gas flow due to an excellent configuration of the inlet/exhaust porting. The huge 2.23-inch intake and 1.71-inch exhaust valves- larger than the exotic Tunnel Port, and semi-hemispherical combustion chambers further evidenced the Cleveland’s competition breeding. Some of the water jacket passages needed to be slightly modified to suit, but the 351 Cleveland heads/302 Windsor block combination became the basis of a Trans-Am winner.

In late 1968 the engine was track tested at Riverside against two others under consideration (as we have already covered)- the unloved Tunnel Port 302 and the more exotic Gurney-Weslake headed 302 which prevailed at Le Mans in 1968 and 1969 in the JW GT40’s. Although the Gurney-Weslake motor, with its all-alloy casting and integral inlet manifold proved the fastest of the three- followed by the Boss and the Tunnel Port, the Boss version was chosen given its use of existing production componentry and therefore the ease and cost of producing it.

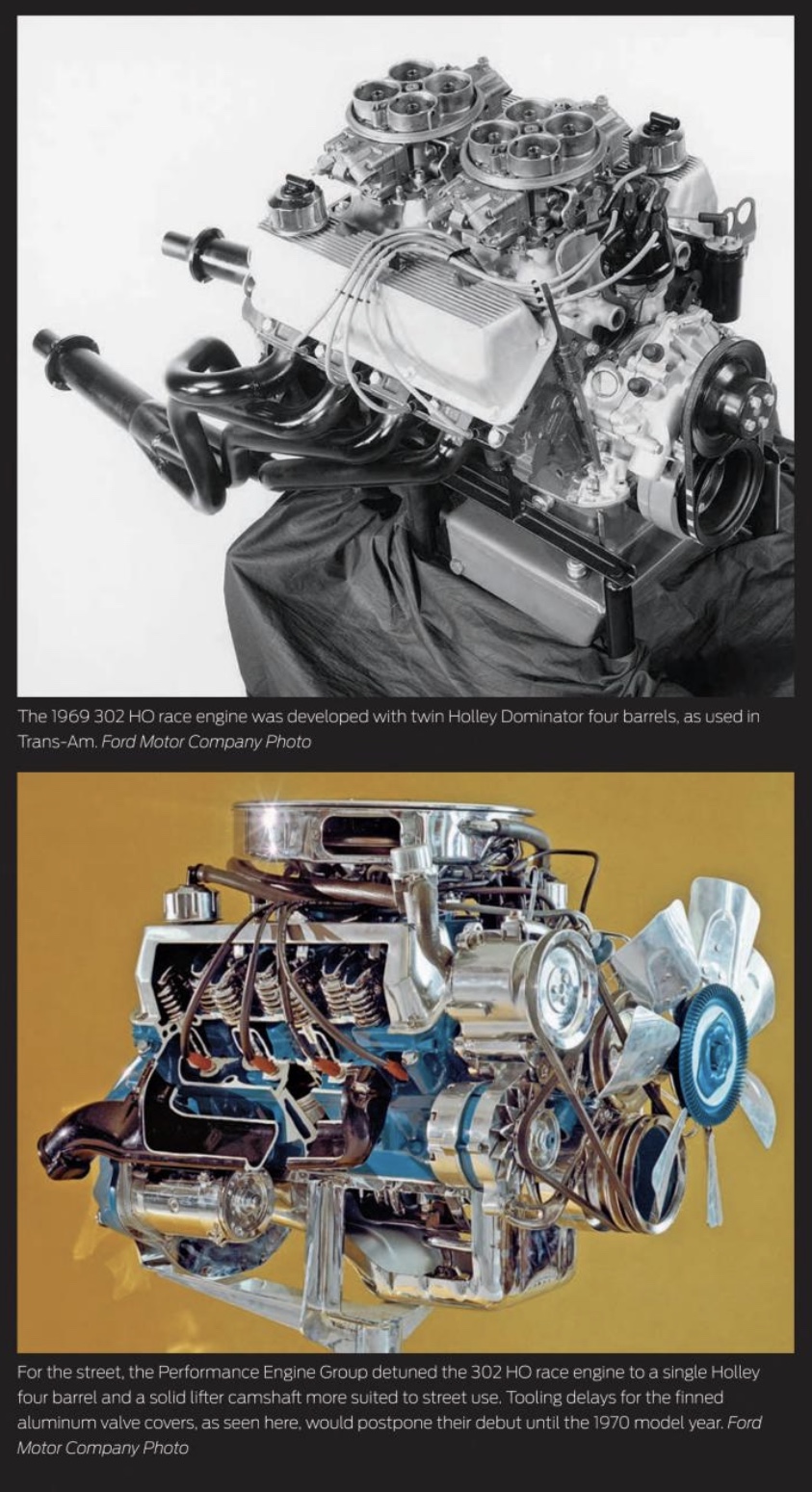

The Boss 302 was produced in road and full race specifications- 110 special race versions were cast featuring four-bolt bottom ends, ‘dry-deck’ head sealing (ie crushable o-rings that seated in grooves at the top of each cylinder bore as opposed to conventional head gaskets) and a different oil system design to suit the Cleveland heads. These were equipped with lightweight valves, stronger valve springs, screw-in rocker studs, steel guide plates for the solid lifter pushrods, 1.73:1 aluminium roller rockers and improved top end oiling.

The induction system comprised two 1050cfm (or 1235cfm) Holley Dominator four-barrel carburettors mounted on a short runner, single plane alloy inlet manifold. A special offset distributor was needed to clear the front carb, they were fed cool, dense air via a fully enclosed airbox connected to twin inlet pipes mounted behind the grille. The Boss 302 roadie was fitted with a single 780cfm Holley.

A variety of induction systems were trialled during the Boss race engine’s development, including four twin-choke downdraught 48mm IDA Weber carburettors which proved very successful on Moffat’s car- those carbs were enlarged to 51mm chokes.

The crankshaft was made of forged steel, was cross-drilled with an anti-frothing windage tray, high volume oil pump with triple pick-ups and a big capacity baffled sump to combat oil surge. Connecting rods had much meatier big end supports were attached to 12:1 forged alloy pistons (road versions used 10.5:1 compression ratio).

Large diameter, equal length tubular steel exhaust headers dumped the spent gases through huge side pipes, a large capacity aluminium radiator and oil cooler were used.

In 1969, Ford claimed 470bhp (350kW) by mid season and it was good for 8000rpm in short bursts, drivers complained that the Boss 302 had the Tunnel Port’s lack of low and mid-range torque but it also had formidable top-end punch.

Ford’s official power ratings for the factory rev-limited Boss 302 road car were a modest 290bhp (216kW) @ 5800rpm. These quoted figures were aimed at keeping the insurance companies happy, in reality a street Boss was good for circa 350bhp (260kW) with the 6150rpm factory rev limiter disconnected.

Transmission and drivetrain

Two variants of the Ford Top Loader four speed gearbox were available in the road car- a wide-ratio version (2.78 1st gear) was standard and a close-ratio (2.32 1st gear) unit was optional. Top Loaders with a variety of ratios were available for the racers.

Boss Mustangs were equipped with a nodular iron cased nine-inch differential assembly and indestructible 31-spline axle shafts, the standard rear axle ratio was 3.50:1 with optional 3.91 and super short 4.30 gear sets to choice. A remote oil cooler and Traction-Lok limited-slip diff were factory options. The racers were fitted with a pair of diff oil coolers located under the car in front of the rear axle.

Cockpit

For Trans-Am duty, all the standard carpet, seating and interior trim were removed except the dash-pad which had a purpose-built instrument panel. A deeply dished sports steering wheel, competition seat with a padded head rest attached to the roll cage and a multi-point harness were used.

There was also an auxilliary switch box on the tunnel and an on-board fire extinguisher system. The rear edge of the driver’s door was secured internally by additional bonnet pin-style clips top and bottom, to ensure the door would not spring open due to impact damage in the heat of battle.

The interior of Moffat’s car after restoration- very much as it left Bud Moore’s (AMC)

‘I entered the 1969 Southern 60 at Sandown and booked passage for myself and the Mustang on a part-passenger, part-cargo aircraft out of New York. The drama started in the air. I’d hopped a plane to make it to JFK International to supervise the loading of the car but we got stuck in a massive mid-air holding pattern. We advanced to fourth landing slot when the pilot came on and said we were low on fuel, and had no option but to divert to Washington.’

‘I arrived in New York late that night to be told the Mustang had already been loaded and would I please take my own seat. I finally persuaded a steward to peep in the hold. He did and reported that there was a big grey car back there that looked like it was going faster than the plane.’

(AMC)

Moffat and crew at ‘711’, Mustang early days (AMC)

In Australia..

‘The Trans-Am was delivered to a holding yard and my only way of moving it to the earthern-floor workshop at 711 Malvern Road in a timely fashion was by towing it. I hitched a rope to the front of the world’s most valuable race car and flat towed it behind my Econoline van.

At ‘711’ we examined this beautiful gift for the first time. It was not a Mustang at all. For a start it had been made lightweight by a process of elimination that had stood the test of time throughout race-car development. Fuel tanks were dropped lower and the engine was discretely sunk in its bay to provide a better centre of gravity and even better handling.

We didn’t start the car in the workshop. We’d save that for Sandown.

Peter Thorn painted the Mustang red. Most people assumed it was Coca-Cola’s corporate colours but we weren’t that sophisticated and neither were they. We thought the car looked so good we wanted to paint it Ferrari red.

We arrived at Sandown and our first hit out and the car wouldn’t go. It started with a magnificent crackle and I drove out of the pits, heading for the back straight, when it stuttered and stalled. Back in the pits we went over everything. The electric fuel pump was not getting fuel through to the engine.

That’s when I chased the line all the way from the front to the rear and found under my driver’s seat a surplus of rubber fuel tube tied tightly in a knot. We undid it and shortened it. Fuel flowed and we were away.’

Moffat crew sort the fuel feed problem during those first laps at Sandown- note the TV crew and proximity of the houses. We are on the old pit straight just past the pitlane exit/paddock entry. Moff has his back to us and Peters Corner (AMC)

Problem sorted- off we go, no mirror @ this stage, note Coke sponsorship from day 1 (AMC)

‘To say the car created immense interest was an understatement. A guy from Ford arrived and placed a huge blue Ford decal on the car. I politely removed it and replaced it with a discrete white one that I’d brought from the States. A person from Ampol put a sticker on and I left it there because I assumed money or kind would follow. It didn’t.’

‘At its first race meeting, the Mustang won three races out of three. It was going to be something to write home about’, Moffat won the Southern 60 from Terry Allan’s Chev Camaro, Jim McKeown, Lotus Cortina Mk2 and Peter Manton, Morris Cooper S. ‘Mallala, my first round of the ATCC, was a disaster and it was a forebear of the season. The new engine flown in from the States put me on the front row of the grid alongside Jane and Geoghegan. But two laps later it blew when I was challenging Jane for second. When we pulled the engine down we found it to be bog standard. I’d not been sent a racing engine but a completely stock unit’ Moffat related to Smailes.

Sex on wheels- too good to race! In the Sandown paddock on that first May 1969 weekend (SS Auto Memorabilia)

Moffat opens the 302’s taps through the kink on Sandown’s back straight looking quite bucolic. Pete Geoghegan at right alongside Terry Allan’s Camaro and Jim McKeown’s Mk2 Lotus Cortina back a bit (unattributed)

‘There’s one word to describe the Mustang’s first season and that’s ‘harrowing’. Seasons two, three and four were better but the Mustang never did win the ATCC, and that’s a cause of immense disappointment to me. In 1969 it never even got on the board, never even scored a point. It even suffered humiliating DNFs and DNS (did not start) in some of the non-championship races. From 1970 to 1972 it cemented its position as one of the most successful and admired cars in the country.’ Checkout this piece on the 1969 ATCC; https://primotipo.com/2018/02/01/1969-australian-touring-car-championship/

‘In the 23 ATCC races it contested until its forced retirement at the end of the 1972 season, it won 10, finished on the podium another four times, claimed 14 pole positions and set four lap records. It figured in some of the most controversial incidents in the championship, starred in front of the biggest crowd ever at Oran Park and played a lead role in the touring car battle regarded as the best of all times. (Bathurst ATCC round Easter 1972) Yes in the annual title fight, the best it could manage was a second and a third.’

In the US, despite a two team approach Ford was again beaten by Penske in 1969 despite the Mustangs being the quickest cars in the early rounds- they took the first four races. Some of the 302 Trans-Ams were destroyed during the year which dissipated what had been a good start. Ford was said to have cut its Trans-Am budget by as much as 75% in 1970 but Bud Moore’s two car entry of mildly updated 1969 cars finally did the trick- before Ford pulled the pin altogether.

Geoghegan from Moffat, Sandown, May 1969- in front but not the way they finished (R Davies)

As I wrote at the outset, this article is about a small period of a long and vastly successful career.

Allan is an icon, a guy we all saw occasionally until quite recently at the circuits keeping an eye on his sons racing career.

He lived close by- it always amused me and warmed my heart to occasionally see him pushing a shopping trolley affectionately around Woolies in Toorak Village behind wife number two, Susan!

In the last couple of years Moff’s battle with Altzheimers Disease and family squabbles over the loot has been made public which is terribly sad, and common though it is, its not the way a lion of the circuits somehow deserves to see out his days.

In that sense John Smailes’ book ‘Climbing The Mountain’, an autobiography he wrote together with Allan ended up being incredibly timely, first published as it in September 2017. He has managed to package up an incredibly interesting and beautifully written story which would simply be impossible now. Do buy it, I bought it in the last week to check some facts and can see how great swags of it have been lifted from it in the sources I found.

Special Vehicles Activity, Advanced Concepts Engineering Activity, Kar-Kraft…

The material below should be the subject of an article on its own titled something like ‘Ford Total Performance: Motor Racing’- a mammoth topic.

For the moment included are some undated Ford Motor Company documents which provide immensely valuable snippets of information about how the FoMoCo organised its ‘Advanced Concepts Engineering’ from a corporate structural perspective.

Whilst the document is undated the models of cars referred to puts it into the early seventies. Clearly the material is internally focussed- it’s the sort of document one puts together at budget and business plan submission time or when seeking to get a company to invest funds in a new activity or direction.

All of the material in this part of the article is from the Fran Hernandez Archive, now deceased, given his senior positions within Ford, the foregoing may well be correct or ‘thereabouts’.

(F Hernandez)

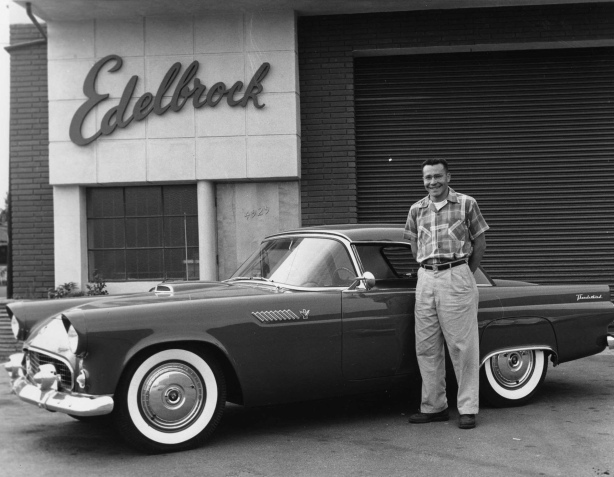

Great shot of Fran and Thunderbird outside Edelbrock- he was Vic Edelbrock’s Machine Shop Foreman circa 1955.

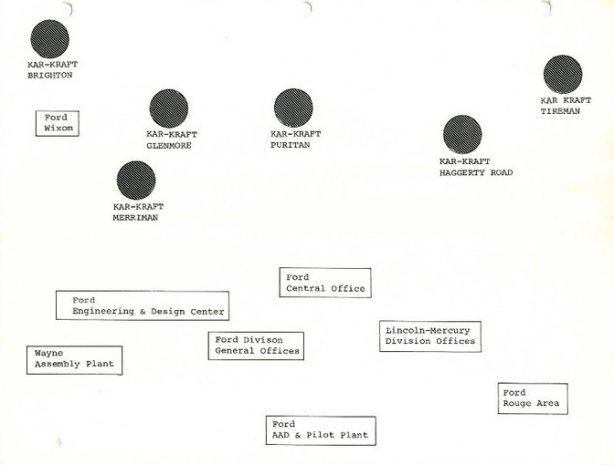

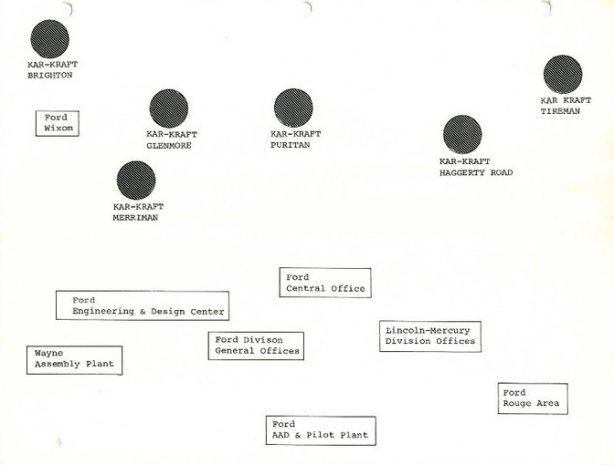

Interesting also is this corporate structure document below as it relates to entities which orbit around Kar-Kraft- more interesting would be the overall Ford organisational structure and the way ‘Special Vehicles Activity’ fitted in. If you can enlighten me please do so.

All of these entities were on Ford’s Rouge Complex with Kar-Kraft close by- all of which makes eminent sense for all the obvious reasons. K-K were still in business as late as 1984 when Jack Mountain owned it according to Doug McLean, ‘at that time the workshop was busy with projects for Renault-Elf, AMC, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Plymouth. Chevy, Chrysler and…Ford.’

In the Ford heyday the K-K sites comprised the following; Haggerty, Dearborn 10,000 sq ft including the engineering department, component prototyping, engine build shop- Brighton, Michigan a complete automotive assembly line of 65,000 sq ft spread over 11 acres- the Trans-Am 429s were built on this site. Glenmore, at Glenmore Street and Grand River was (and the plant still is) in Redford, comprised 18,000 sq ft, its focus was the construction and modification of special test and show vehicles. Merriman in Glendale, Livonia was a new factory of 24,000 sq ft housing the vehicle engineering department, it too still exists. Tireman was an engine build and engine engineering facility- this older plant at 8020 Tireman Street, Detroit is still extant also.

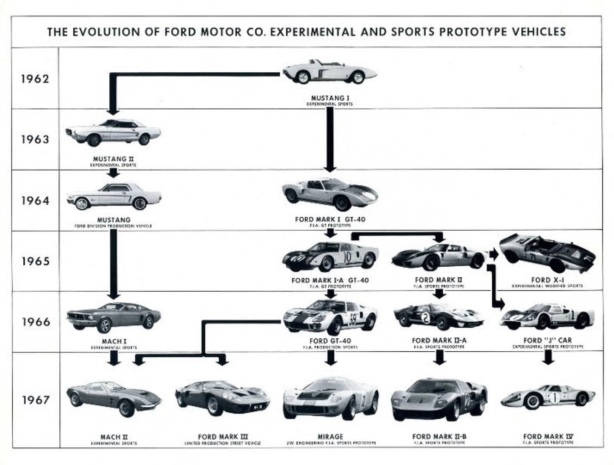

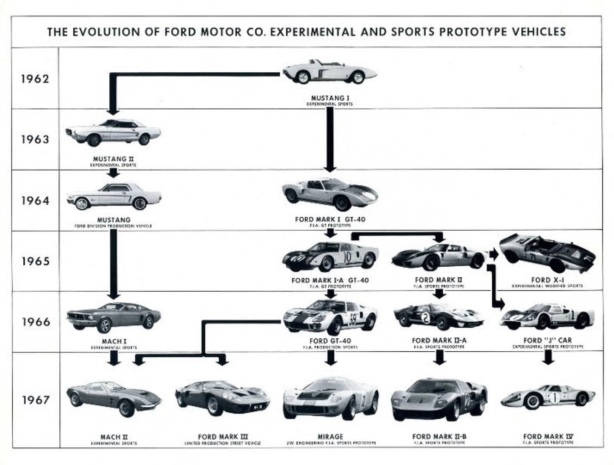

The Ford ‘Experimental and Sports Prototype Vehicles’ family tree as at 1967, possibly a part of the earlier document but perhaps not given the difference in end-dates.

Etcetera…

(AMC)

Moffat- second from the right at the rear, Chapman, Clark, the rest of the boys and Lotus 38 Ford after the Indianapolis triumph of 1965.

(AMC)

Victory lap for Moffat, left, at Waterford Hills date uncertain.

(FoMoCo)

Mercury Cougar key team members gather around one of the cars in early 1967- Parnelli Jones, Fran Hernandez, Dan Gurney and Bud Moore.

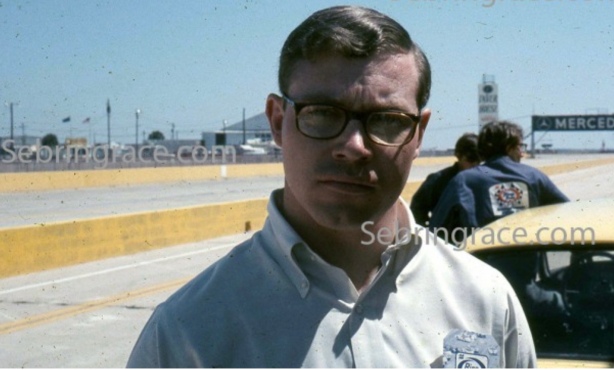

Allan Moffat and fellow Aussie touring car star Jim McKeown at Daytona in early 1967- they ran a Lotus Cortina with ‘Jim’s most powerful twin-cam in the world’ fitted- the mechanic is Vince Woodfield (Allan Moffat)

Daytona 1968..

Sebring 1968..

It can’t be that bad, surely?

Moffat was a pro-racer at a time in Australia where he was competing against racer/businessmen to whom competition was a weekend sport whereas for Moffat it was his business and his demeanour always reflected that- he was easily cast in Australia as the foreign ‘baddie’ given his intense focus on the task at hand- success, to put ‘bread on the table’. He took Australian Citizenship in the early 2000’s.

(D Friedman)

The two Shelby cars in line astern, and below Horst Kwech looking as happy about things as Moffat looks displeased. He forged a great career in the US after cutting his racing teeth in Australia- he grew up in Cooma, in the foothills of the New South Wales alpine country.