Sans-culottes

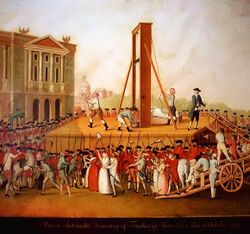

Sans-culottes (French, “without knee-britches”) was a term given to the poorer members of the Third Estate during the French Revolution due to the fact that they often didn’t wear any knee-britches, or other pants of any sort at all. Made up of shopkeepers, artisans, craftsmen, and other ordinary Frenchmen disillusioned with the increasing violence of the revolution’s radicalism and the confining nature of the period’s leg garments, the sans-culottes provided perhaps the only viable political foil to the pants-wearing bourgeois Jacobins, the gaudily-dressed royalists, and the skirt-wearing and prissy aristocrats. Though their political influence would be surpassed by the sans-têtes (French, “without heads”) during Robespierre’s guillotine-intensive Reign of Terror, and would end entirely with Robespierre’s joining of the sans-têtes in 1794, [1] the sans-culottes remain an influential and important aspect of French cultural and political history. Even today, the sans-culottes ideals of liberty, fraternity and pantslessness strike a chord of resonance with the French people.

Background

The political scene of early 1790s France was dominated by various oddly-specific political clubs. Foremost among these were the Jacobins (French, “Team Jacob”),[2] a group that vehemently supported the centralization of political power in the French Republican state; the abolition of the French aristocracy, monarchy and clergy; the empowerment of the French bourgeois professional class; and the wearing of leg-garments.

It was in this final regard that the Jacobins were particularly radical, especially given the broader historical context in which the club operated: the Jacobins endorsed the notion that the wearing of leg-garments by members of the Third Estate was not only permissible, but an inalienable right for all, regardless of social position. This radical notion flew in the face of France’s feudalistic class distinctions and aristocratic privileges, which for centuries had relegated such amenities and frivolities as drinking water, chamber pots and pantaloons as things to be enjoyed strictly by the ruling class and clergy. What’s more, the traditional garment of the French peasantry, the sacques (French, “the sack”), had always lacked arm and leg sleeves—the Jacobins’ insistence on clothing the public, therefore, not only challenged the aristocratic status quo, but it upset traditionalists within France as well.

Regardless of conservative and traditionalist opposition, the Jacobins implemented their revolutionary vision of pantsing the public when they effectively gained power in the spring of 1793.

The Sans-Culottes

The Jacobins’ radicalism was hardly endorsed by all segments of French society, however, and a number of oppositional groups soon crystallized. The Feuillants opposed the official Jacobin policy toward the French king—regicide—and instead favored a limited monarchy based upon the British model, which relegated the powers invested in the monarch to those merely ceremonial or interesting to tourists. The deposed aristocrats naturally resented the loss of their social position and property,[3] and sought a return to France’s traditional social order so they could get all their stuff back. The Girondists, meanwhile, strongly opposed calling themselves ‘Jacobins,’ and opted to call themselves the Girondists instead.

By far the strongest and most important bastion of Jacobin opposition, though, was a loosely-organized movement of urban, working-class Frenchmen who opposed the restrictions the Jacobins placed on the freedom of their limbs: the sans-culottes.

Demographics and Ideology

The precise demographic makeup of the sans-culottes has long been a source of scholarly debate, and in the attempt to understand the genesis of organized freeballing in Revolutionary France, many theories have been forwarded. The broad consensus among historians of the period is that the sans-culottes represented a reaction to Jacobin radicalism, as expressed by their open and flagrant flaunting of the Jacobins’ hegemonic leg garment doctrine. However, Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm argues that the sans-culottism offered no real alternative to bourgeois Jacobin ideology and that, fundamentally, the sans-culottes simply didn’t like wearing pants.[4]

Sans-Culottism and the French Revolutionary Wars

Regardless of their exact demographic makeup and ideological grounding, sans-culottism played an integral role in France’s numerous wars during the revolutionary period. In 1792, the fledgling French revolutionary government decided that the best way to consolidate their power was to declare war on longtime ally Austria.[5] Because France’s aristocrats had no real inclination to fight and the Jacobins were too busy running the war to actually engage in combat themselves, the bulk of France’s revolutionary armies from 1793 to 1794 were made up of sans-culottes.

In battle, the sans-culottes’ radical freedom of extremities gave the French revolutionary armies a number of decisive advantages over the invading Austrians, and, later, the invading Prussians. The French army’s total lack of leg encumbrances meant it could maneuver in the field quickly and more comfortably. Furthermore, the sight of 30,000 pantsless Frenchmen was a sight that shocked opposing armies—this, in turn, provided the French with a key psychological advantage over their adversaries. Gunter von Leipzig, a Prussian colonel, recalled the French revolutionary furor and lack of drawers during the Battle of Valmy, and wrote of it in his memoirs:

| “ | Arrayed against us were some twenty or thirty thousand Frenchmen, all without pantaloons. Though the fire from our artillery was intensive, they held their lines with conviction, and shot their rifles with discipline. Upon running out of ammo, the inspired Frenchmen would take up their other rifles into their hands and charge our lines with great furor. Such scenes as those in the calamity of battle were terrifying, and a bit icky. | ” |

The Decline of the Sans-Culottes

Though the sans-culottes and their loose[6] ideology enjoyed much influence during the early years of the French revolutionary period, the popularity of the movement began to wane by 1794. Indeed, the invention of the guillotine and the subsequent sans-têtes movement it spawned coupled with the particularly chilly autumn and cold winter of 1794 virtually put an end to the movement. Though systematic below-the-waist nudity would remain a powerful force for the remainder of the French Revolution, it never again enjoyed the level of popularity, organization and legitimacy brought to it by the sans-culottes.

Legacy

To this day, sans-culottism and its associated philosophies still remain relevant in France, particularly on its beaches.

Footnotes

- ↑ The sans-têtes were a political movement founded in 1789 by Bernard-René de Launay, the governor of the Bastille when the fortress was stormed. Other notable sans-têtes include Marie Antoinette, Arnaud de Laporte, and King Louis XVI.

- ↑ The Jacobins are typically noted for their longstanding rivalry with the British Edwardians, who endorsed the stratification of society along lines of economic status and social class, as well as popular vampire literature.

- ↑ The estates of the French aristocracy were Europe’s largest and most valuable, and contained the world’s largest concentration of powdered wigs and white, dainty stockings.

- ↑ Because Hobsbawm is a Marxist historian, his theory regarding the sans-culottes also involves at least some mention of the word ‘proletariat’.

- ↑ This notion would later be adopted by Napoleon Bonaparte, who would come to base his entire foreign policy around declaring war on Austria.

- ↑ In more ways than one.