Ivan Ermakoff's 2008 book Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications is dense, rigorous, and important. It treats two historical episodes in close detail -- the passing of Hitler’s enabling bill by the German Reichstag in the Kroll Opera House in March 1933 (“Law for the Relief of the People and of the Reich”) and the decision by the National Assembly of the French Third Republic in the Grand Casino of Vichy to transfer constitutional authority to Marshal Pétain in July 1940. These legislative actions were momentous; "the enabling bill granted Hitler the right to legally discard the constitutional framework of the Weimar Republic," and the results in France were similar for Pétain's government. In both events major political parties and groups acquiesced in the creation of authoritarian legislation that predictably led to dictatorship in their countries and repression of their own parties and groups. Given that these two events largely set the terms for the course of the twentieth century, this study is of great importance.

The central sociological category of interest to Ermakoff here is "abdication" -- essentially an active decision by a group not to continue to oppose a social or political process with which it disagrees. Events are made by the actions of the actors, individual and collective. But Ermakoff demonstrates that sometimes events are made by non-action as well -- deliberate choices by actors to cease their activity in resistance to a process of concern.

Abdication is different from surrender. It is surrender that legitimizes one’s surrender. It implies a statement of irrelevance. When the act is collective, the statement is about the group that makes the decision. The group dismisses itself. It surrenders its fate and agrees to do so, thereby justifying its subservience. This broad characterization sets the problem. Why would a group legitimize its own subservience and, in doing so, abdicate its capacity for self-preservation? (xi)Based on a great deal of archival research as well as an apparently limitless knowledge of the secondary literature, the book sheds great light on the actions and inactions of the individual and collective actors involved in these enormously important episodes of twentieth-century history. As a result it provides a singular contribution to the theories and methods of contentious politics as well as comparative historical sociology.

The book is historical; but even more deeply, it is a sustained contribution to an actor-centered theory of collective behavior. Ermakoff wants to understand, at the level of the actors involved, what were the dynamics of decision making and action that led to abdication by experienced politicians in the face of anti-constitutional demands by Hitler and Pétain. Ermakoff believes that the obvious theories -- coercion, ideological sympathy, and the structure of existing political conflicts -- are inadequate. Instead, he proposes a dynamic theory of belief formation and decision making at the level of the actor through which the political actors arrive at the position they will adopt based on their observations and inferences of the behavior of others with regard to this choice. Individuals retain agency in their choices in momentous circumstances: "Individuals fluctuate because (1) they are concerned about the behavioral stance of those whom they define as peers and (2) they do not know where these peers stand. Individual oscillations are the seismograph of collective perceptions. Their uncertainty fluctuates with the degree of irresolution imputed to the group." Ermakoff wants to understand the dynamic processes through which individuals arrive at a decision -- to abdicate or to remain visibly and actively in opposition to the threatened action -- and how these decisions relate to judgments made by individuals about the likely actions of other actors.

Ermakoff's key theoretical concept is alignment: the idea that the individual actor is seeking to align his or her actions with those of members of a relevant group (what Ermakoff calls a "reference group"). "By alignment I mean the act of making oneself indistinguishable from others. As a collective phenomenon, alignment describes the process whereby the members of a group facing the same decision align their behavior with one another’s." For individuals within a group it is a problem of coordination in circumstances of imperfect knowledge about the intentions of other actors. And Ermakoff observes that alignment can come about through several different kinds of mechanisms (sequential alignment, local knowledge, and tacit coordination), leading to substantially different dynamics of collective behavior.

Jon Elster and other researchers in the field of contentious politics and collective action refer to this kind of situation as an "assurance game" (link): an opportunity for collective action which a significant number of affected individuals would join if they were confident that sufficient others would do so as well in order to give the action a reasonable likelihood of success.

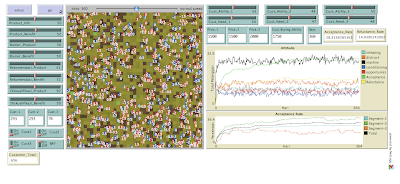

Though Ermakoff does not directly suggest this possibility, it would appear that the kinds of decision-making processes within groups involved here are amenable to treatment using agent-based models. It would seem straightforward to model the behavior of a group of actors with different "thresholds" and different ways of gaining information about the likely behavior of other actors, and then aggregating their choices through an iterative computational process.

Much of the substance of the book goes into evaluating three common explanations of acquiescence: coercion, miscalculation, and ideological collusion. And Ermakoff argues that the only way to evaluate these hypotheses is to gain quite a bit of evidence about the basis of decision-making for many of the actors. A meso-level analysis won't distinguish the hypotheses; we need to connect the dots for individual decision-makers. Did they defer because of coercion? Because of miscalculation? Or perhaps because they were not so adamantly opposed to the fascist ideology as they professed? But significantly, Ermakoff finds that individual-level information fails to support any of these three factors as being decisive.

Part III moves from description of the cases to an effort at formulating a formal decision model that would serve to explain the processes of alignment and abdication described in the first half of the book. This part of the book has something in common with formal research in game theory and the foundations of collective action theory. Ermakoff undertakes to provide an abstract mid-level description of the processes and mechanisms through which individuals arrive at a decision about a collective action, illustrating some of the parameters and mechanisms that are central for the emergence of abdication as a coordination solution. This part of the book is a substantial addition to the literature on the theory of collective action and mobilization. It falls within the domain of theories of the mechanics of contentious politics along the lines of McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly's Dynamics of Contention; but it differs from the treatment offered by McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly by moving closer to the mechanics of the individual actor. The level of analysis is closer to that offered by Mancur Olsen, Russell Hardin, or Jon Elster in describing the logic of collective action.

Consider the logic of the "abdication game" that Ermakoff presents (47):

The "authoritarian challenger" is the leader who wishes to extend his powers beyond what is currently constitutionally permissible. The "target actors" are the groups and parties who have a say in modification of the constitution and legislative framework, and in this scenario these actors are assumed to have a blocking power in the legislative or constitutional process. If they remain unified in opposition the constitutional demands will be refused and either the status quo or an attempt at an unconstitutional seizure of power will occur. If they acquiesce, the authoritarian challenger will immediately undertake a transformation of the state that gives him unlimited executive power.

There is a difficult and important question that arises from reading Ermakoff's book. It is the question of our own politics in 2020. We have a president who has open contempt for law and political morality, who does not even pretend to represent all the people or to respect the rights of all of us; and who is entirely willing to call upon the darkest motivations of his followers. And we have a party of the right that has abandoned even the pretense of maintaining integrity, independent moral judgment, and a willingness to call the president to account for his misdeeds. How different is that environment from that of 1933 in Berlin? Is the current refusal of the Republican Party to honestly judge the president's behavior anything other than an act of abdication -- shameful, abject, and self-interested abdication?

It seems quite possible that the dilemmas created by authoritarian demands and less-than-determined defenders of constitutional principles will be in our future as well. This book was published in 2008, at the beginning of what appeared to be a new epoch in American politics -- more democratic, more progressive, more concerned about ordinary citizens. The topic of abdication would have been very distant from our political discourse. Today as we approach 2020, the threat of an authoritarian, anti-democratic populism has become an everyday reality for American society.

One other aspect of the book bears mention, though only loosely related to the theory of collective action and abdication that is the primary content of the book. Ermakoff's discussion of the challenges that come along with defining "events" is excellent (chapter 1). He correctly observes that an event is a nominal construct, amenable to definition and selection by different observers depending on their theoretical and political interests.

Events are nominal constructs. Their referents are bundles of actions and decisions that analysts and commentators abstract from the flow of historical time. This abstraction is based on a variety of criteria—temporal contiguity, causal density, and significance for subsequent happenings—routinely mobilized by synthetic judgments about the past. Because events are temporal constructs, their temporal boundaries can never be taken for granted. They take on different values depending on whether we derive these boundaries from the subjective statements left by contemporary actors (Bearman et al. 1999) or construct them in light of an analytical relevance criterion derived from the problem at hand (Sewell 1996, 877).Ermakoff returns to this theme at the end of the book in chapter 11. The approach here taken towards "events" is indicative of one of the virtues of Ermakoff's book (as well as the work of many of the comparative historical sociologists who have influenced him): respect for the contingency, plasticity, and fluidity of historical processes. We have noted elsewhere (link, link, link) Andrew Abbott's insistence on the fluidity of the social world. There is some of that sensibility in Ermakoff's book as well. None of the processes and sequences that Ermakoff describes are presented as deterministic causal chains; instead, choice and contingency remain part of the story at every level.

(Levitsky and Ziblatt's How Democracies Die provides a stark companion piece for Ermakoff's historical treatment of the ascendancy of authoritarianism.)