This month’s New York magazine features a set of articles about popular music today and why questions of plagiarism seem to dog so many hit songs. I was happy to contribute an article teasing out the controversies around Ariana Grande’s “7 Rings” by taking a musicological deep-dive into the disputed musical figure in question, a resurgently popular rhythm that some would call a Scotch Snap.

You can find an online version, complete with technomusicological examples — a few mashups and a mini-mega-mix! — over at Vulture. They’ve gone and slicked up the Ableton screengrabs I made, which is nice, but I also like the charm and simplicity (especially the ability to track audio, notation, and video) of the originals. Here, for instance, is the Scotch Snap megamix I worked up — just follow the bouncing cowbell!

I first started noticing the Scotch Snap a while back, and I flagged it on the blog here in March 2014, proposing that the “remarkable spread” of the “stuttered, splattered, staccato syllables” popularized by Chicago rappers Lil Reese and Chief Keef made it second only to the Migos flow. I noted that it was already a trope among such pop singers as Rihanna and Beyonce, and I suggested that “perhaps I need to make a supercut to make my point.”

Well, it only took me 5 years, but here we are. How funny to look back, especially in the wake of this Ariana Grande piece, and see myself writing that “far as I can tell, that Chicago drill flow has less of a history than 8th note triplets.” Now I can tell farther. Far farther. As I explore in the article, while it’s important to recognize how rappers have crucially contributed to the vogue for this rhythm, the Scotch Snap has a long history, spanning all manner of music in the United States and pointing back to Scotland (as well as West Africa). In the words of musicologist Philip Tagg,

The Scotch snap is used by Henry Purcell, Béla Bartók, Mahalia Jackson, Woody Guthrie, Stevie Wonder, Ry Cooder, James Brown, Buck Owens etc., etc., etc. You’ll find it in Strathspeys, traditional English ballads, Appalachian fiddling, string band music, spirituals, white gospel, black gospel, rock music, even in West African time lines, but you won’t hear it in mariachi, mbaqanga or MPB, nor in the musics of South or Central Europe, including (continental) European art music.

I’m indebted to Tagg’s amazing video on the Scotch Snap for helping me connect all these dots. Looking back, I’m surprised I didn’t reference his video in that blog post. I count Tagg as a technomusicological pioneer and have been assigning his videos in my classes for years. (Tagg’s Milksap Montage is a classic mega-mix of 52 midcentury pop songs using the same 4 chords, and it helped convince me that mega-mixes and montages could compellingly tell musicological stories.)

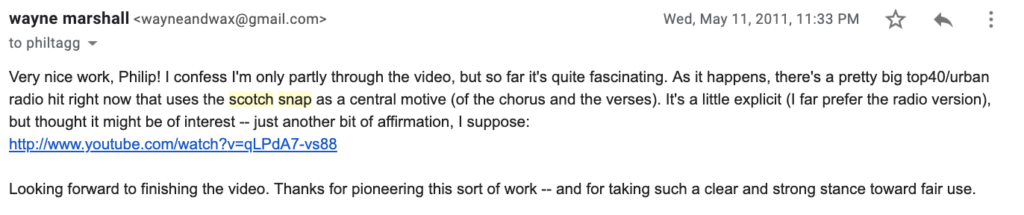

Going through my records, I see that I even emailed him back in May 2011, as soon as he shared his video with the IASPM list. I was eager to report that one could also hear the Scotch Snap in current rap songs, such as Travis Porter’s “Make It Rain” — an example that I probably should have included in my mega-mix, especially as it comes out around the same time as “Pretty Boy Swag,” which Soulja Boy would like to pose as patient zero for this rhythmic meme.

While we’re on the topic of additional examples, if I had another crack at the mega-mix — and thought people could deal with a few more minutes of follow-the-cowbell — I would definitely add Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space,” BTS’s “Fake Love,” Rich Brian’s “Dat $tick,” and Florida Georgia Line’s “Swerve,” each of which shows how the rhythm, as (re-)popularized by rappers, has gone global and jumped genre-lines.

But telling as much of the story as my mini-mega-mix does is maybe enough, and a little late is better than never. That said, having filed the story and produced the mix back in February, I was gutted to get scooped by popular YouTube music-explainer, Adam Neely, who published a Scotch Snap video covering a lot of the same ground — and also pivoting on Ariana Grande — in the middle of March, as my own work was slowly working its way through fact-checking and other editorial processes. So it goes. Like the rhythm itself, this story has been in the air, and “7 Rings” made as good a platform for telling it as any.

Neely’s a Berklee alum, and my students brought his work to my attention last year. I like what he does (especially his Giant Steps / music+math piece), and he did a fine job on the Scotch Snap story. In the end, Neely gets more into the musical and linguistic weeds, where my article focuses more on the historical context and questions of plagiarism and appropriation. They can complement each other, to be sure. (I just wish my own video could do numbers like his, which, in under a month, has netted nearly half a million views!) I’m grateful that he linked to my montage and added my name to the credits, where, par for the course, I discovered that a French fellow was walking this trail back in October 2018 (and used the same Purcell sample that I grabbed via Tagg).

That said, I suppose this blog is as good a space as any to express some skepticism over Neely’s suggestion that the beat of dancehall and reggaeton is derived from the rhythmic tendencies of Jamaican English and Spanish. While there may be some happy overlap between that 3+3+2 beat (aka dembow) and idiomatic stress patterns in those languages, that beat is at bottom a dance rhythm — not a speech rhythm — and is far older than those languages, and more African.

I’m also not convinced that the Scotch Snap is all that (relatively) rare in Jamaican music and language, especially given that Scottish-African cultural interplay happened there too. Off the top of my head, I can recall that Elephant Man’s “The Bombing” (2001) drops Scotch Snaps throughout the verses, though I’ll have to start listening more closely for it across the reggae repertory.

While we’re talking Jamaica, allow me to include here my favorite of the souped-up videos in the article. In this case, the video design, combined with the text I prepared, serves to make clear what we’re hearing when we’re hearing it (especially if you use headphones) — far better than I do waving around my cursor. I’m glad to finally share this story with the world, especially since, although Junior Reid apparently enjoyed the mashup, he lost interest in the lawsuit and it never went anywhere. I would have been quite curious to know how persuasive this may have proven in court (or in settlement negotiations), or in the court of public opinion, to which I now submit it.

One of the problems I noticed when scanning the Scotch Snap literature is that the data — i.e., the corpora — referenced in studies such as the Temperleys’ (PDF) are deeply Eurocentric, making it difficult to come to broader conclusions about the geographical distribution of the rhythm. I’d be very curious to know what sort of patterns and proclivities would emerge given a wider, larger, and much more global sample. Perhaps the increasing popularity and recognition of the Scotch Snap will help spur more research in that vein.

I’ll be keeping my ears peeled, and now, I suspect, so will you.

Magisterial, Dr. Wayne, with thanks for all that you share with us, your admirers.