Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury helped win the Civil War with his many financial innovations, and was an ardent advocate of emancipation.

-

Spring 2024

Volume69Issue2

Editor's Note: Walter Stahr is a historian whose essay “The Struggles of Edwin Stanton” appeared in the Fall 2017 issue of American Heritage. His most recent book is the widely praised Salmon P. Chase: Lincoln’s Vital Rival, in which portions of this essay appeared.

Zion Church, the largest black meeting house in Charleston, South Carolina, was packed for a political meeting on the afternoon of May 12, 1865. Most of the five thousand people there had started their lives enslaved and gained their freedom only a few weeks earlier, when the Union army finally arrived in town.

The main topic of this meeting, as the last rebel die-hards fought the last battles of the Civil War, was reconstruction — the process of forming new state governments in the South, and whether blacks, as well as whites, would participate in the process. The afternoon’s first speaker, a white Union general, said that blacks had earned the right to vote through their service during the war. The remarks of the second speaker, a black army major, were interrupted by the arrival of the Chief Justice of the United Stares.

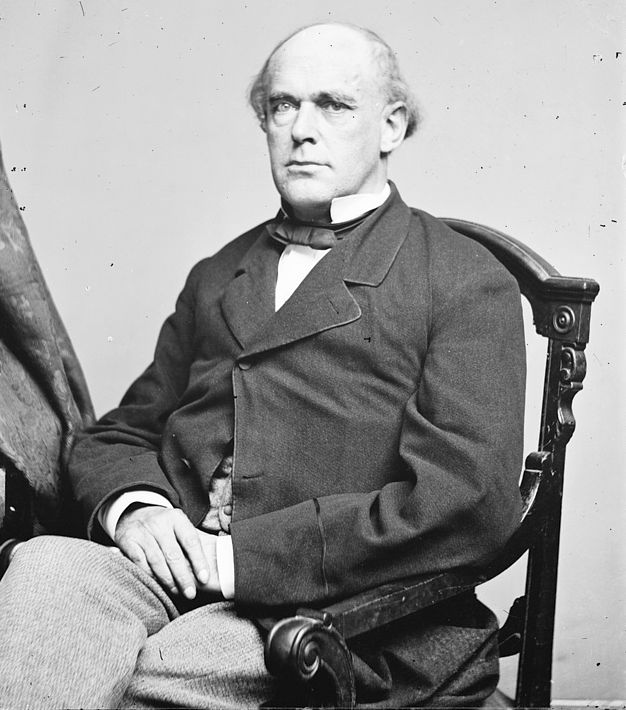

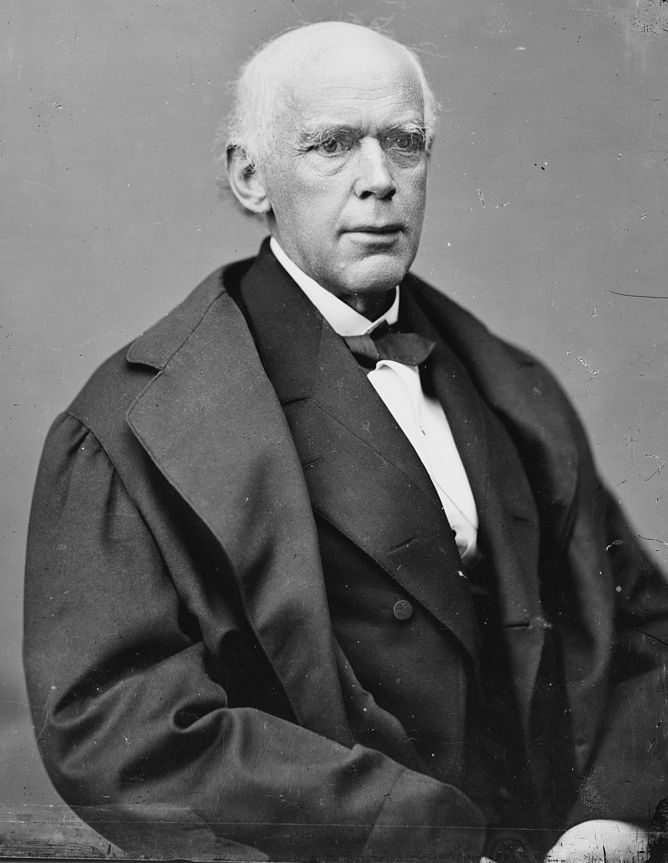

The black crowd stood and cheered, and the military band played “Hail to the Chief,” as Salmon Portland Chase walked down the aisle and up to the platform. “More than anyone else, he looked the great man,” one of his friends recalled: six feet tall, solid, strong, clean-shaven, nearing sixty.

The crowd cheered him not because of his work on the Supreme Court (he had been chief justice for only a few months) or because of his work as Treasury Secretary during the Civil War (although some called him “Old Greenbacks” for his role in creating the new green paper currency and putting his own face on it). No: the black Charleston crowd cheered because Chase was known as a lawyer who had defended fugitive slaves, and a leader who, in his various government roles, who always argued against slavery and in favor of basic rights for blacks.

Chase did not disappoint his audience. He said that their future was at last largely in their own hands. “Let the soldier fight well, let the preacher preach well, let the carpenter shove his plane with all his might, and the planter put in and gather in as much corn or cotton as he can.... Act thus, and I have no fears for your future.” He told them that he had been speaking for black voting rights for twenty years, since he had given a similar speech in Cincinnati, but he cautioned that mere speeches did not have much effect, for, in spite of his efforts, black men still could not vote in Ohio.

Salmon Chase had been pressing the new president, Andrew Johnson, to insist on black voting in the reconstruction process, and he believed that Lincoln's successor might well follow this course. If there was a delay, however, Chase advised the blacks of Charleston that they should “go to work and show that the United Scares government was mistaken in making the delay. If you show that, the mistake will be corrected.” When he finished, the crowd cheered him nine times.

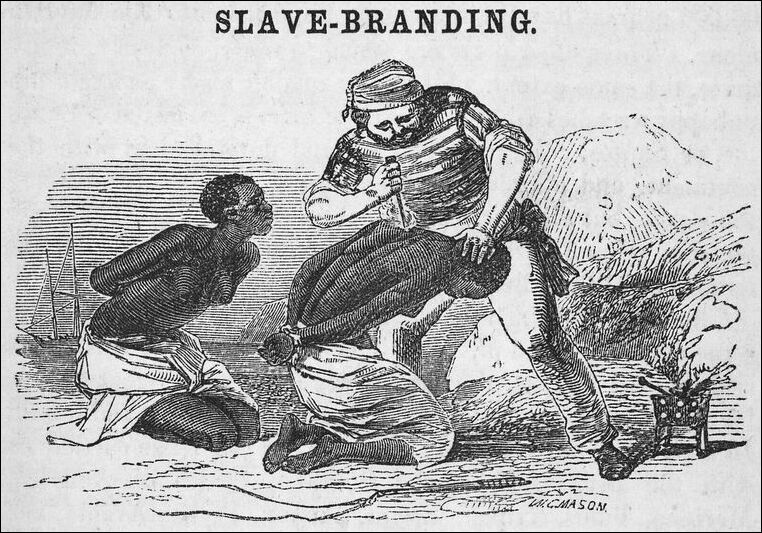

Who was Chase at this fluid moment in American history? How did his views change from his youth, when he wrote that “little cause exists for that sickly sympathy which many at the North feel or affect to feel with the fancied suffering of the slave,” to his mature years, when he became a leading antislavery agitator?

Why did the Republican Party, the party which he had done more than any other man to create, choose Abraham Lincoln rather than Chase as its presidential candidate in t860? Why did Lincoln select his rival Chase for the vital task of managing the federal finances during the Civil War and then, near the end of the war, make him chief justice? And why was he touring the South in the last days of the Civil War and giving what many would view as a controversial, political speech?

Born in rural New Hampshire in 1808, Chase spent some of his youth in southern Ohio before returning east to attend Dartmouth College. After graduating, he lived for four years in the nation’s capital, teaching school and reading law. He moved to Cincinnati to start his legal career, where he married the first of his three wives, all of whom died young. He was elected to the city council as a member of the Whig Party in 1840, but, a year later, disgusted by the subservience of the two main political parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, to the slave states and the slave masters, Chase left the Whigs and joined the tiny Liberty Party.

Chase’s course, in the 1840s and early 1850s, was very different from that of Lincoln, another midwesteen lawyer who was active in politics. While Chase was busy building and leading anti-slavery parties, Lincoln remained a loyal Whig, perhaps holding similar opinions, but rarely expressing them in speeches. In the 1844 presidential election, Lincoln gave speeches for his Kentucky hero, the senator and slaveholder Henry Clay. Chase worked that year for the Liberty Party, publishing a “Liberty Man’s Creed,” in which he declared that the party was simply carrying out the dreams of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, to end slavery through peaceful political processes.

A year later, Chase received a silver pitcher from the free blacks of Cincinnati to thank him for his legal work representing those accused of being fugitive slaves. In a speech that would often be quoted against him, Chase urged the state to amend its constitution so that blacks would have the right to vote. “True democracy makes no enquiry about the color of the skin, or the place of nativity, or any other similar circumstance,” he said. Lincoln, in the course of his long legal career, never represented a fugitive slave, but once served as lawyer for a master in an attempt to keep a black woman and her children in slavery in the free state of Illinois. Chase represented alleged fugitives so often that he was known as the “attorney general for runaway negroes.”

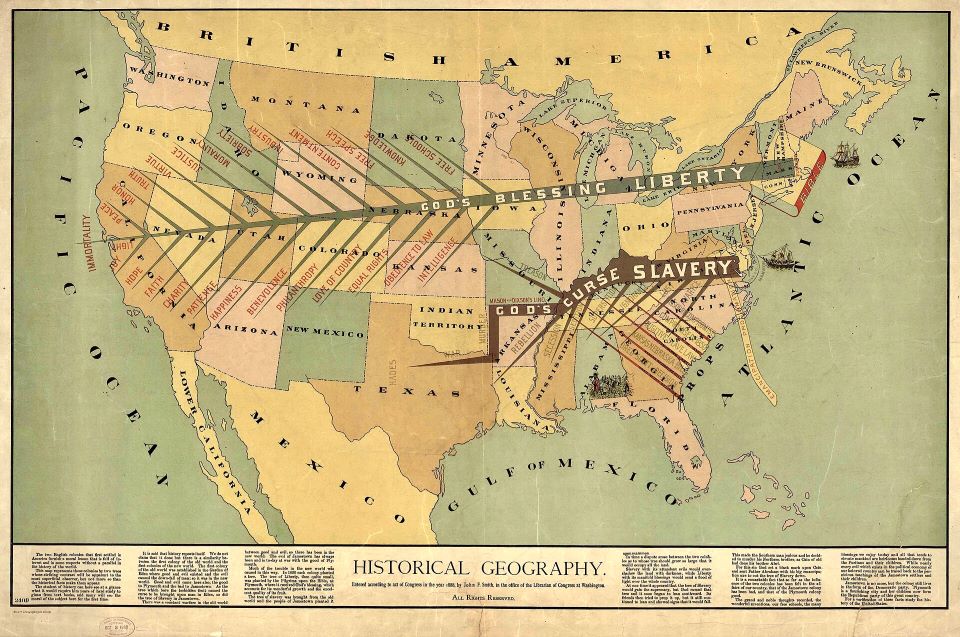

In 1848, near the end of his single term in Congress, Lincoln campaigned for the Whig presidential candidate, Zachary Taylor, another southern slaveowner. Chase was the key leader that year in forming the Free Soil Party, a combination of the Liberty Party and anti-slavery elements of the Whig and Democratic parties. After the Free Soil national convention, at which he was the presiding officer, Chase campaigned relentlessly for the Free Soil Party, helping it secure almost 15 percent of the votes in the northern stares. Early the next year, an even split between the two major parties in the Ohio legislature allowed the Free Soil Party, through a coalition with the Democrats, to send Chase to Washington as one of the state's two federal senators.

The major speeches of Chase’s during his six years in the Senate were against slavery, notably challenging the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which he denounced for opening the immense northern part of the Louisiana Territory to slavery, and thereby violating the Missouri Compromise. Chase helped start the fire and fan the flames of northern outrage against the Nebraska bill, and from this conflagration would emerge a new political party, the Republicans, who committed to Chase’s brand of political anti-slavery. It was only at this stage, in the midst of the furor over the Kansas-Nebraska bill, that Lincoln started to give speeches against the extension of slavery, although he remained a Whig until early 1856.

Meanwhile, in 1855, the Republicans of Ohio nominated and then elected Chase as the first Republican governor of a major state. He served two terms, each lasting two years, and worked to protect black rights and to improve public education. “No safer or more remunerative investment of revenue is made by the state than in the instruction of her youth,” he declared. In 1858, some national Republican leaders favored Stephen Douglas, the Democrat, over Abraham Lincoln, the Republican, in the Illinois senate race, hoping that Douglas would divide the Democratic Party.

Chase was one of the few out-of-state leaders who supported Lincoln, speaking in Chicago and elsewhere during that historic campaign. But, even though Chase and Lincoln were then in the same party, they did not yet agree on black rights. Chase would never have said (as Lincoln did in the course of this race) that he was not “in favor of bringing about, in any way, the social and political equality of the white and black races” and that he was not “in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people.”

Chase was a leading candidate for the 1860 Republican nomination, but it was Lincoln who received the nomination at the Chicago convention, in part because he was seen as less radical on slavery than Chase or his former Senate colleague, William Henry Seward. Chase was understandably disappointed, but he overcame his chagrin and campaigned widely and effectively for Lincoln, speaking in the East, in New Hampshire and New York, and in the West, in Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan, and even in the slave state of Kentucky.

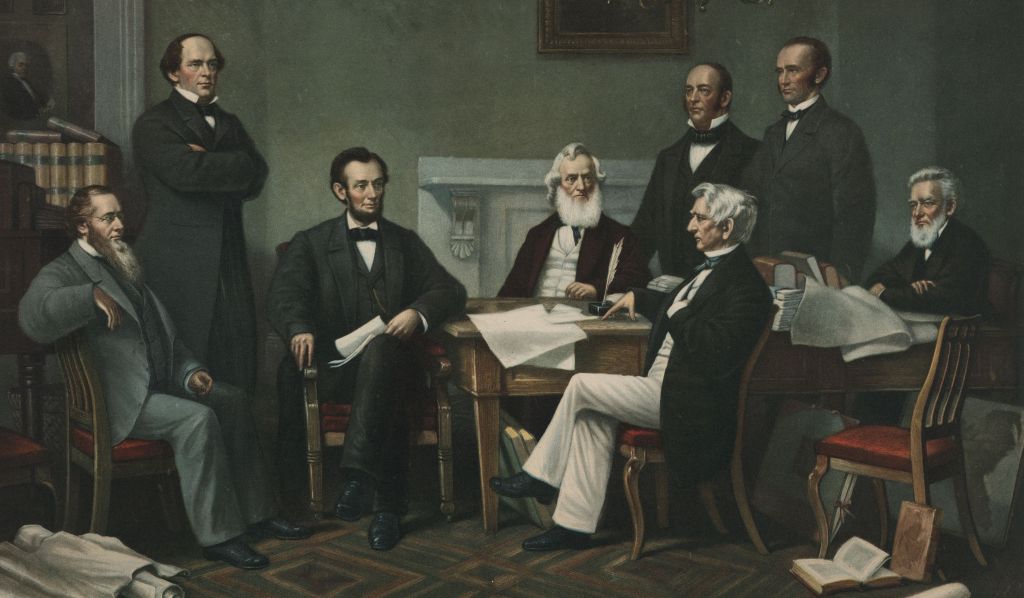

The next year, as some Southern states seceded, and as civil war approached, Lincoln offered Chase the second-most- prestigious position in his Cabinet, as Secretary of the Treasury. Chase accepted, starting work in March 1861.

He managed, in his three years as the head of the Treasury, to raise the hundreds of millions of dollars that were necessary to enable the Union to win the Civil War, in part through direct appeals to the public to invest in government bonds. He also used the wartime crisis to create a national banking system and a single national currency. Before the war, American currency was a confusing mix of foreign and domestic coins and more than ten thousand different types of banknotes, which were very difficult to value and easy to counterfeit.

After the war, currency consisted of coins minted by the federal government and notes printed and backed by the federal government. Before the war, there were no national banks, only a host of almost 2000 state banks, ranging from the large and stable to the small or spurious. After the war, under legislation devised and pushed through Congress by Chase, there was a strong system of national banks.

He did not forget the slaves or former slaves during the Civil War. No other member of Lincoln's Cabinet was in such close touch with the army officers, government officials, and private volunteers working to help the blacks who had fled from slavery to freedom. Chase pressed Lincoln to emancipate the slaves, he favored enlisting black volunteers in the army, and he urged Lincoln to insist that Southern blacks have the right to vote.

He was Lincoln’s one serious rival within the Republican Party for the 1864 presidential nomination, something that now seems odd and outrageous, but was less so at the time, when presidents generally served a single term and were often succeeded by their senior Cabinet officers.

Chase pulled out of the presidential race in February, but continued his Treasury work until June, and then campaigned for Lincoln’s re-election in the fall. When Chief Justice Roger Taney - whose most infamous opinion, in the Dred Scott case, was that blacks had no status as citizens - died in October, Lincoln considered many men before naming Chase, whose views on civil rights were almost the complete opposite of Taney’s, as the nation’s next chief justice.

Chase remained deeply concerned about blacks and black rights while on the Supreme Court. Within weeks of becoming chief justice, he organized the admission of the first black member of the bar on the court's legal staff. On the eve of Lincoln’s second inauguration, in March 1865, the nation’s foremost black leader, Frederick Douglass, called for tea at the home of his friend Chase, whom he had known since “early anti-slavery days.”

A few weeks later, just before Lincoln’s murder, Chase wrote the president two long letters urging him to speak out for black voting rights. Chase was not satisfied with Lincoln’s approach of giving voting rights to only a few intelligent blacks or former soldiers; Chase wrote the president that he was now “convinced that universal suffrage is demanded by sound policy and impartial justice alike.”

On the morning that Lincoln died, April 15, 1865, it was Chase who administered the oath of office to Andrew Johnson. Both in person and by letter, while he was on the southern tour that took him to Charleston, Chase pressed Johnson to adopt the approach he called “universal suffrage and universal amnesty,” linking the right to vote for blacks with amnesty for former rebels. After encouraging Chase for a while, Johnson rejected his agenda and allowed whites to control the first phase of reconstruction.

But by the time Chase died in 1873 at the age of 65, black men had the right to vote throughout the United Stares, and there was a black member of the Senate and several black members of the House. Much work remained, but he could take considerable pride in what he and his colleagues had accomplished in ending slavery and securing black rights.

Millions of Americans see Chase’s name every day — the Chase National Bank was named for him by friends not long after his death — but they know little about his life and work. If Americans know anything about this man and slavery, they do not know how his views evolved over time; how he gradually became one of slavery’s most vocal and successful opponents.

If Americans know anything about Chase’s relations with Lincoln, they know that he was Lincoln’s rival, but not that Lincoln could never have become president without the vital work that Chase had done in the two preceding decades — organizing anti-slavery political parties — nor the way in which the 16th president respected and relied upon Salmon Chase.

From SALMON P. CHASE: Lincoln’s Vital Rival by Walter Stahr. Copyright © 2021 by Walter Stahr. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, LLC.