Why Lady Chatterley's Lover is about much more than just sex

It was one of the first bonkbusters. A book so scandalous that no one dared to publish it in its full form until an era-defining obscenity court case. DH Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover is a novel synonymous with sex and sin. Famously, during the 1960 obscenity trial, the chief prosecutor stated: "Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?"

But perhaps the most surprising revelation about the work is how overlooked by readers the various other elements were, in comparison to the sexual content. In his Radio 4 series Opening Lines, writer and producer John Yorke unpacks the ideas and impact surrounding great books, including Lawrence's classic. So, other than all the yearning, groping and gyrating, what other motifs are there to discover in Lady Chatterley's Lover?

Class

The plot of Lady Chatterley’s Lover is pretty lean. Lawrence wanted to cram a number of underlying ideas into the novel without distracting the reader with acres of action. As John states in Opening Lines, "the story itself is almost absurdly simple." The rich and privileged Sir Clifford Chatterley is injured during World War I. His war injuries mean he is no longer able to have sex, altering the relationship and dynamic with his young wife Constance, who begins a steamy affair with working-class gamekeeper Mellors.

In 1920s Britain these class-straddling lovers would have sent shockwaves through society.

While her husband understands, even encourages, his wife's adultery (he wants an heir), it's this class divide that proves to be the most scandalous aspect of the encounter. As John says: "That’s forbidden."

An affair, even an adulterous one, is acceptable, but an affair that develops into love with a working man is unthinkable. In 1920s Britain, when the novel was written, these class-straddling lovers would have sent shockwaves through society. Amongst other things, it was the hypocrisy of these attitudes that Lawrence wanted to highlight, often encouraging readers to empathise with the adulterous couple, and sometimes putting obstacles to that empathy in the way.

War

In Opening Lines, John describes Lady Chatterley's Lover as "Lawrence's lament for a million young British soldiers who lost their lives". Lawrence was deeply affected by the horrors of the Great War. The opening lines of the novel ('Ours is essentially a tragic age…') immediately lets the reader know that the book concerns the after-effects of an unimaginably brutal conflict.

The lovers are guinea pigs for the quest for recovery after the horrors of the war.

Lawrence's rage is aimed at those who led ordinary people into this barbaric slaughter and those whose shattered lives were changed forever, including Constance's husband Clifford. Was any sort of normality or recovery possible after such a painful event? This is what Lawrence hoped to discover. As John states: "Our lovers are the guinea pigs for that quest."

Tradition

For Lawrence, the horrors of the war failed to supply any sort of progress. One theme that emerges in the book is the loss of tradition, replaced by something inferior: mass industrialisation. As John points out, Lawrence felt "rage at the destruction of an old way of life. Rage at the destruction of the land itself."

Lawrence came from Nottinghamshire mining stock and witnessed first-hand the devastation that mining wrought on the workers and also on the landscape. In the book, Clifford is on a personal journey as a member of the landed gentry to working as an industrialist, running mines of his own and following in his family's footsteps, while Mellors, living in the woods, is a symbol of a forgotten, pastoral England.

'It's a simple tale, fueled by anger'

John Yorke on what Lady Chatterley's Lover tells us about its author's attitude to war.

Truth

One of Lawrence's obsessions is the quest for truth and, in particular, being true to ourselves when it comes to love and desire. As John says: "The sex isn't there to titillate, it's an attempt to find truth." The most important thing to the injured Clifford is his land and he becomes focused on an heir, even willing to accept an illegitimate child as his own (yet not the child of a gamekeeper). Mellors represents the carnal and physical, but also trapped in the legacy of his own past. Constance is trapped between the two, trying to navigate her place and her desire.

The sex isn't there to titillate, it's an attempt to find truth. The book seeks to balance tenderness and rage.John Yorke

What Lawrence desired was an understanding that intellectual pursuits are no more worthy than physical desire. Denying our desires is what creates friction and unhappiness. Constance starts to realise that both body and mind are required to live a fulfilled life. We can and must accept both to be truly satisfied.

Progress

Although Lawrence's work is completely different from the stream of consciousness prose of James Joyce or the complex rhythms of TS Eliot, he did belong among the Modernists. These were artists who felt that the old approach to society had led to the atrocities of the First World War and creative work needed to ask awkward questions. "New modes of thought were needed if such a catastrophe was to be avoided again," as John states in Opening Lines.

Lawrence was determined to push boundaries. The premise of the book, plus the language used (with explicit words peppered throughout) would have been inconceivable in 1927, when it was written. But Lawrence refused to compromise his vision. In order to publish it, Lawrence had to pay a small Italian printer to print it privately because no British publisher would touch it.

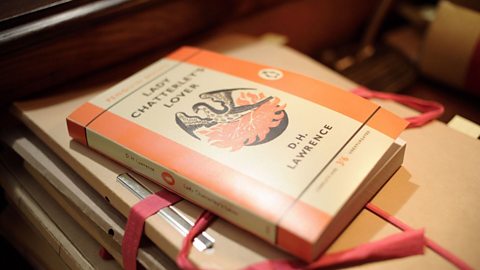

It wasn't until the 1960s that a complete, uncensored version was released in Britain. Penguin Books, under the leadership of Sir Allen Lane was determined to add the unexpurgated version to the other volumes of Lawrence's work they were publishing in paperback. A paperback priced at 3/6 would make it available to the masses. This led to the famed obscenity trial. Ironically, it was the coverage and notoriety of the trial that led to Lady Chatterley's Lover becoming a far more well-known book. A book known for sex but concerning far more than that. As John states: "Everyone should read it if they want to understand our world."

Listen to episode 1 and 2 of Opening Lines: Lady Chatterley's Lover here.

Listen to the whole series of Opening Lines on BBC Sounds and discover the themes and impact of some of our most well-known books, plays and stories.

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

Open Book

Immerse yourself in new fiction and non-fiction books, Open Book talks to authors and publishers and unearths lost classics.

-

![]()

How many of these 100 novels have you read?

After a passionate debate, our Bookclub panel has come up with this surprising literary selection.

-

![]()

Bookclub

Led by James Naughtie, a group of readers talk to acclaimed authors about their best-known novels.

-

![]()

A Good Read

Books worth reading.